More languages

More actions

| Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela República Bolivariana de Venezuela | |

|---|---|

Map of Venezuela according to the 2023 referendum. Light green territories are not recognized by the UN. | |

| Capital and largest city | Caracas |

| Official languages | Spanish |

| Recognized national languages | 26 indigenous languages |

| Government | Federal presidential republic |

• President | Nicolás Maduro (de jure, kidnapped by the US) Delcy Rodríguez (de facto) |

• Vice President | Delcy Rodríguez |

| Area | |

• Total | 916,445 km² |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 30,518,260 |

| Currency | Venezuelan bolívar (VED) |

| Calling code | +58 |

| ISO 3166 code | VE |

| Internet TLD | .ve |

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela,[1] is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands in the Caribbean Sea. It borders Colombia to the west, Brazil to the south, Trinidad and Tobago to the northeast, and Guyana to the east. Modern Venezuela is a anti-imperialist state ruled by the left-wing Chavismo movement.

In 1960, Venezuela produced 30% of the world's oil.[2]:184 Venezuela has been the target of hostility from the US imperialists due to its significant reserves of oil, as well as its recent trend of electing left-leaning progressive governments which prioritize social programs and the implementation of what some observers describe as Socialism of the 21st century.[3]

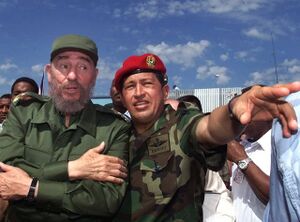

Under the anti-imperialist government of Hugo Chávez, unemployment decreased by almost half, GDP per capita more than doubled, infant mortality decreased, and extreme poverty dropped from 23.4% to 8.5%.[4]

History[edit | edit source]

Spanish colonialism[edit | edit source]

In 1777, a treaty between the Spanish and the Dutch defined the Esequibo River as the eastern border of the Captaincy General of Venezuela.

After losing control of its Thirteen Colonies in North America in 1776, the British Empire sought to take over parts of South America. In the early 19th century, it annexed the Guayana Esequiba region from Spanish-occupied Venezuela and the Tigri region from Dutch-occupied Suriname. Around the same time, Venezuela became independent from the Spanish.

In 1797, the British seized the island of Trinidad from Venezuela. The Spanish colonizers recognized it as British territory five years later with the Treaty of Amiens.[5]

Early republic[edit | edit source]

In 1815, Britain recognized the 1777 borders of Venezuela. In 1822, under the orders of Simón Bolívar, Ambassador José Rafael Revenga criticized British intrusions west of the Esequibo. After Gran Colombia broke apart, the Michelena-Pombo Treaty of 1833 divided the Guajira Peninsula roughly in half between Colombia and Venezuela. The Venezuelan parliament rejected the treaty and continued to dispute the region until 1883.[5]

In 1840, the Royal Geographic Society of London sent Robert Schomburgk, a German geographer, to map the border between Venezuela and British Guyana. His map claimed the sparsely populated Guayana Esequiba and Tigri regions as part of Guyana. In 1841, Alejo Fortique, the Venezuelan ambassador to the UK, argued the Esequibo issue and made the British agree to future negotiations on the border. After he died in 1845, Venezuela agreed to postpone border negotiations.[6]

General Ezequiel Zamora led the peasantry in the Federal War (1859–1863). He fought against the ruling class while trying to redistribute land and wealth.[7]

United States of Venezuela (1864–1953)[edit | edit source]

After the Federal War, Juan Cristósomo Falcón became President and appointed Antonio Guzmán Blanco as representative to Britain. Britain rejected Guzmán Blanco's attempts to solve the border dispute in the 1870s and 1880s. In 1883, Spain also ended the Guajira dispute in favor of Colombia, and President Guzmán Blanco recognized the result. Venezuela ended relations with the UK in 1887 and mistakenly asked for the USA's help against Britain.

In 1895, the United States asserted the Monroe Doctrine, which considers the Americas to be territory for colonization by the USA rather than colonization by Europe. The UK initially refused to negotiate until the USA threatened war. In 1897, after the UK refused to negotiate with Venezuela, which it considered uncivilized, the USA decided to negotiate on Venezuela's behalf without taking its interests into account. The UK and USA created a tribunal of five people: two from the UK and three from the USA. The last member, Frederick Fyodor Martens, was a Russian diplomat who wanted Russia and Britain to cooperate in invading Central Asia. In 1899, the tribunal created the Paris Arbitration Award, which surrendered Guayana Esequibo the British.[6] The affair was an early instance of the Monroe Doctrine being invoked and the U.S. asserting itself as an imperial power.[8][9]

From 1902 to 1903, Venezuela was blockaded by European navies.[10]

During the Dutch-Venezuelan crisis of 1908, the U.S. Navy helped Venezuelan Vice President Juan Vicente Gomez seize power in a coup. Gomez endeared himself to Washington and Wall Street by granting highly lucrative concessions to foreign oil companies including Standard Oil (ExxonMobil today) and Royal Dutch Shell.[9]

In December 1936, the oil workers of Maracaibo went on strike.[2]:176

In 1949, the Statesian Judge Otto Schoenrich published the Mallet-Prevost Memorandum. Severo Mallet-Prevost had been one of the Statesian lawyers at the 1899 Paris tribunal along with former U.S. president Benjamin Harrison and others. The memorandum described the tribunal in detail and said that the British had forced the U.S. jurors to accept an unequal treaty towards Venezuela.[6]

Fourth Republic (1953–1999)[edit | edit source]

Oil production increased after Mexico nationalized its oil in 1938, doubling in the 1950s. The dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez, who ruled from 1952 to 1958, used oil revenues to fund construction projects that did not help the workers. In 1958, a new progressive government led by the Democratic Action party planned to nationalize the oil industry.[2]:176–9 Juan Pérez helped establish OPEC in 1960.[2]:184

When Guyana became independent from the British in 1966, Venezuela agreed to temporarily leave the Esequibo region under Guyana's control until they could reach a permanent solution. However, Venezuela did not recognize Guyananese authority over the disputed region. In 1970, with the Port of Spain Protocol, Prime Minister Eric Williams of Trinidad and Tobago made an agreement that Guyana and Venezuela would maintain bilateral ties and that Venezuela would not claim the Esequibo until 1982.[6]

Carlos Andrés Pérez ruled Venezuela from 1974 to 1979.[7] Starting in 1977, Venezuelans' incomes began to continually fall over a 25-year period, while oil prices began to decline in the early 1980s.[11] Luis Herrera Campins of the Christian Democratic Party (COPEI) was president from 1979 to 1984.[12]

Hugo Chavez, a soldier in the national army, along with others, formed the Bolivarian Revolutionary Army 2000 in 1982, and in 1983 re-named it to Bolivarian Revolutionary Movement 200, or MBR-200. The number 200 referred to the 200th anniversary of the birth of Simón Bolívar.[7]

Jaime Lusinchi was president of Venezuela from 1984 to 1989 and began his term following an adjustment plan agreed with the International Monetary Fund, leading to a major devaluation of Venezuela's currency. During this period, Venezuela had to allocate half of all its export earnings to the IMF in order to pay its debt.[11]

Carlos Andres Perez was again president from 1989 to 1993.[7] Although Perez had run on an anti-neoliberal platform,[13][11] he implemented the neoliberal Great Turnaround in 1989, having called in the IMF for a reform package, just weeks after being elected.[11][13] The reforms were announced on February 15 and included IMF demands such as liberalization of all prices except for basic staples, an increase of oil prices, privatization of state-owned companies, the elimination of import taxes, and a free market in interest rates.[11] These capitulations to the IMF led to a rapid increase in prices, such as the price of public transport increasing by 30% overnight.[11] This led to mass protests, which came to be known as the Caracazo, in which numerous civilians were killed by state forces.[7][14][13] Estimates of the amount of deaths and disappeared persons range from 276 to up to three thousand.[14][11] Perez was later impeached.[13]

Perez's successor, Rafael Caldera, continued neoliberal rule and allowed foreign imperialists to own the economy.[7]

In 1992, Hugo Chávez and the MBR-200 attempted to overthrow the neoliberal government and start a revolution. Although this was unsuccessful, after being released from prison, Chavez led the formation of the Movement of the Fifth Republic (MVR), a coalition of left-wing parties, in 1997.[7]

Bolivarian government (1999–present)[edit | edit source]

Chávez presidency[edit | edit source]

The Bolivarian Revolution refers to a left-wing populist social movement and political process in Venezuela led by Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez who founded the Fifth Republic Movement and later the United Socialist Party of Venezuela. The "Bolivarian Revolution" is named after Simón Bolívar, an early 19th-century Venezuelan and Latin American revolutionary leader. According to Chávez and other supporters, the "Bolivarian Revolution" seeks to build a mass movement to implement Bolivarianism—popular democracy, economic independence, equitable distribution of revenues, and an end to political corruption—in Venezuela. They interpret Bolívar's ideas from a populist perspective, using socialist rhetoric.[15]

In 2004, Venezuela began the National System of Missions to address poverty, illiteracy, and health and housing problems. It also formed the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America with Cuba.[7] The Venezuelan and Cuban governments also teamed up for Operation Miracle, which provided treatment for people with eye problems in the Global South. The Great Housing Mission Venezuela has constructed over 4.2 million homes for poor and working class Venezuelans, with a goal of 5 million by 2025.[16] In 2006, construction began on a planned socialist community, Ciudad Caribia, which was the brainchild of Chávez.

Venezuela fully nationalized its oil industry in 2007. At the time, as reported in The Guardian, "amid jubilant scenes, oil workers wearing red T-shirts emblazoned with 'yes to nationalisation' moved into the giant Orinoco basin shortly after midnight after Caracas insisted six of the world's biggest oil companies cede operational control."[17] The Venezuelan government adopted a policy in which the state oil company, PDVSA, must have majority ownership of all projects. Meanwhile, foreign companies would only be allowed to have a minority stake in joint ventures. US corporations such as ConocoPhillips, Chevron, and ExxonMobil, as well as Britain's BP, Norway's Statoil, and France's Total, refused to accept these terms and left the country, agreeing to transfer operational control to state-owned PDVSA.[18][17] ExxonMobil would go on to sue the Venezuelan government. Exxon Mobil's CEO at the time, Rex Tillerson, later became Donald Trump's first secretary of state.[18]

On March 5, 2013, Chávez died after 14 years in office. His vice president Nicolás Maduro took over the office of the presidency. On April 14 an election was held with Maduro being elected president. Opposition candidate Henrique Capriles contested the results and demanded a recount.[19] Arson attacks were carried out on PSUV headquarters, on the home of the electoral council president, and on various social service providers, including against Cuban-staffed health clinics for the poor, thirty-five of which were attacked after opposition journalist Nelson Bocaranda made a tweet to his over one million followers claiming that they were hiding ballot boxes. The attacks of this time resulted in eleven deaths.[20]

Maduro presidency[edit | edit source]

Starting in February 2014, opposition protests known as the guarimbas took place. On social media, images of police brutality from various different countries and time periods were circulated as though they were currently happening in Venezuela, providing so-called evidence of the supposed brutality of the Maduro administration. As author George Ciccariello-Maher points out in Building the Commune,[20] the Venezuelan right wing "had patiently studied the tools, imagery, and social media techniques more often associated with progressive or leftist causes" and used Twitter hashtags such as #SOSVenezuela and #PrayForVenezuela. As Ciccariello-Maher analyzes, despite their progressive veneer, these right-wing protests had "more to do with returning to a neoliberal past" than with "charting a revolutionary future" and involved global networks of foundations and NGOs that have "co-opted the tools of the left":

The 2014 protests—known among Chavistas as the guarimbas for the treacherous barricades they erected—had far more to do with returning to a neoliberal past than with charting a revolutionary future. The hashtag that represented the aims of these middle-class Twitter warriors most honestly was the original one—#LaSalida, “the exit”—pointing toward the goal of regime change at all costs. The way that the protesters appropriated the symbols of the left was no accident, moreover, but instead involved global networks of foundations and NGOs that have gradually co-opted the tools of the left—strategic nonviolence, street protest, and social media—fusing these instead with a young, new Latin American right wing.[20]

Political opposition figures associated with these and previous protests include Leopoldo Lopez and Maria Corina Machado.[20][21][22] The CIA-adjacent National Endowment for Democracy (NED) is among the organizations that have provided funding to Venezuela's opposition groups.[23][21][24] Journalist Roberto Lovato reported in 2014 that he had interviewed opposition youth, writing that "almost all" of the youth he interviewed "were middle- to upper-class university students living in middle-class to ultra-elite neighborhoods of Caracas" and that, when asked, they uniformly rejected any identification with anarchism or Marxism, rather identifying with figures such as dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez and opposition leaders Henrique Capriles, María Corina Machado, and Leopoldo Lopez.[25]

In 2015, the Obama administration of the US declared "the situation in Venezuela" to be an "unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States" and placed sanctions on Venezuela.[26] The sanctions then escalated under the Trump administration in 2017, followed by an economic embargo placed on Venezuela in 2019.[27]

The US maintains a blockade against Venezuela to try to strangle their independent economy. In August of 2021, Peru announced it would no longer participate in the blockade.[28] The blockade against Venezuela even negatively affects US businesses[29] and has caused 40,000 deaths due to lack of food and medicine.[30] Venezuelan capitalists have burned food[31] and buried it underground.[32] Despite this, Venezuela's malnutrition rate has decreased from 13.2% in 2001 to 8.2% in 2017.[33]

In 2021, president Maduro spoke to the UN General Assembly saying that 'we must build a "new world without imperialism"'[34]

Despite their elections being declared democratic by the US-based Carter Center[35], and not having the death penalty[36][37], the US media insists that Venezuela is a dictatorship with no regard for human rights, thus trying to lay the groundwork for "humanitarian interventions"[38]

Despite attempts at economic isolation, the US was forced to re-engage the Venezuelan economy for its oil.[39]

On March 17, 2022, President Maduro announced a new social media app called Ven App which will be used as a means of direct communication with the government, in an effort to help the government reach citizens with better services. It has been inspired by Russia's VK and China's WeChat.[40]

In August 2025, the US began deploying a naval force in the waters near Venezuela. On September 2, the US began a series of deadly bombings on small boats, claiming to target so-called "narcoterrorists". Deadly strikes continued throughout the following months, with the death toll reaching at least 123 as of January 2026.[41][42][43] In December, the US began seizing oil tankers it deemed to be associated with Venezuela, initially seizing two in December 2025.[44] Throughout this time, Venezuela began conducting military exercises and civil militia training,[45] while volunteers increasingly began signing up for Venezuela's civil defense militia.[46][47]

In the early morning of January 3, 2026, the US launched military strikes on Venezuela, targeting both military and civilian infrastructure, and kidnapping president Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores and taking them to the US. The attacks resulted in a death toll of at least 100[48] and the destruction of five scientific research centers[49] and a warehouse of dialysis supplies affecting 16,000 patients.[50][51] In president Maduro's absence, vice president Delcy Rodriguez assumed the role of acting president.[52]

Following the January 3 attacks, the US seized two more oil tankers on January 7, 2026, one in the Caribbean and one between Iceland and Scotland.[44] Throughout the time following the attacks US officials made several comments suggesting that they were prepared to strike Venezuela again if they supposedly "need" to,[53] as well as making comments suggesting they might attack or otherwise target other countries as well, including comments about Mexico, Cuba, Colombia, Iran, and Greenland.[44][54] By January 20, the US had seized seven ships.[55]

Imperialist aggression[edit | edit source]

US coup attempts[edit | edit source]

Chavismo has attracted repeated attacks from the US imperialists to the north, including coup attempts in 2002, 2019, and 2020,[56] among others.[57][58]

In 2002, from April 11 to 13, US-backed[24] reactionary opposition forces and business leaders in Venezuela, who had received NED funding[24] among other forms of support from imperialist forces, briefly kidnapped president Hugo Chavez and purported to abolish the constitution and establish Pedro Carmona, the president of the Venezuelan Federation of Chambers of Commerce (Fedecámaras) as the leader of Venezuela, before the short-lived coup regime was forced out of power by mass mobilizations demanding the return of Chavez, surrounding the presidential palace and refusing to leave until Chavez was returned. On April 13, the presidential guard expelled Carmona from the presidential palace and Chavez was returned to power.[59][60] Opposition forces later attempted to shut down the Venezuelan oil industry in late 2002, lasting for two months until oil workers seized the installations.[61]

In his 2020 memoir The Room Where It Happened, John Bolton, former National Security Advisor under U.S. President Donald Trump, wrote regarding Venezuela:

Shortly after the drone attack [on Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro on August 4, 2018][62], during an unrelated meeting on August 15, Venezuela came up, and Trump said to me emphatically, “Get it done," meaning get rid of the Maduro regime. “This is the fifth time I've asked for it,” he continued. [...] Trump insisted he wanted military options for Venezuela and then keep it because “it's really part of the United States.”[63]

Sanctions[edit | edit source]

The United States and Canada have placed sanctions on Venezuela. Donald Trump encouraged the EU to sanction Venezuela as well.[64] According to a 2019 report by the Center for Economic and Policy Research, 40,000 people had died in Venezuela since 2017 due to US sanctions.[65] As of 2022 the sanctions on Venezuela were reported as totaling around 500 different measures.[66]

The US has been imposing sanctions on Venezuela in various forms since 2005, starting with "targeted" sanctions and expanding their scope over time.[67] In March 2015, the US's Obama administration imposed further sanctions on Venezuela, declaring the "situation" in Venezuela to be an "extraordinary threat to the national security of the United States."[26][68] The first Trump administration further expanded the sanctions.[67] In early 2019, the United States began an embargo of Venezuela's oil industry, the most important sector of its economy, and cut off Venezuela from purchasing chemicals and spare parts needed for the industry to function.[66] In August 2019, the Trump administration froze the assets of the Venezuelan government in the United States and prohibited all transactions with Venezuela unless approved by OFAC.[67]

A 2021 report by United Nations Special Rapporteur Alena Douhan recommended the sanctions be lifted as they undermine human rights and have had a "devastating" effect on the entire population. Furthermore, the report found that the sanctions against the oil, gold, mining, "and other critical economic and life-support sectors, the state-owned airline and the TV industry constitute a violation of international law". The report also stated that "the announced purpose of the 'maximum pressure' campaign of the U.S. administration aimed at changing the Government of Venezuela, violates the principle of sovereign equality of states and constitutes an undue intervention in the domestic affairs of Venezuela that also affects its regional relations."[69]

Boat bombings[edit | edit source]

In August 2025, the US began deploying a naval force to the waters near Venezuela, including amphibious assault ships and other vessels carrying about 6,000 sailors and marines and various aircraft.[41] In September, the US military began a series of deadly bombings on small boats in the Caribbean in waters near Venezuela, claiming the people on them were "narcoterrorists" transporting drugs. The first few strikes were announced by US officials who also posted videos on social media of what was apparently footage of the bombings.[42][41] The first strike occurred on September 2, killing eleven people. The second strike followed on September 15, killing three. US officials declared another attack on September 19, also killing three, with more deadly strikes continuing over the following months.[41] In October 2025, US president Trump openly said that he was considering land operations and that he had "authorized" the CIA to conduct covert operations in Venezuela, saying he did so because Venezuela "emptied their prisons" into the US and because "we have a lot of drugs coming in from Venezuela".[70] As of December 22, 2025, the death toll from the 29 known strikes reached at least 105 people.[41] By January 8, 2026, the death toll was reported to be 123.[43]

Throughout the deployment of US naval forces near Venezuela and the continuing attacks, Venezuela began conducting military exercises as well as civil militia training throughout the country.[45][46] Bolivarian Militia member Armando Urgelles, interviewed in November 2025, stated that the ideological basis of the militia is rooted in the anti-colonial struggle and said that every week, militia members participate in "revolutionary patriotic training which includes theory and political education to learn about our history, our roots, our struggles".[47] Urgelles noted that Venezuela has many critical and strategic minerals and other resources important for the functioning of the capitalist system, making Venezuela a country of strategic geographical importance. Urgelles stated that the militias have "very high morale" and that "just as the militias are prepared for civil duties, we are prepared in the strategic concept of permanent war".[47]

Oil tanker seizures[edit | edit source]

On December 10, 2025, the US seized an oil tanker called Skipper off the Venezuelan coast.[71][41][44] A second, called Centuries, was seized on December 20.[71][41][44] Following the US bombing of Venezuela on January 3, 2026, the US continued seizing ships, including the Marinera (formerly called Bella 1) and the M/T Sophia, both seized on January 7. Marinera was seized between Iceland and Scotland after a weeks-long pursuit, while M/T Sophia was seized in the Caribbean.[44] The US then seized the Olina.[72] On January 15, USSOUTHCOM announced the seizure the Veronica.[73] By January 20, USSOUTHCOM announced the seizure of the Sagitta, at this point reaching a total of seven ships seized.[55]

Military strikes on Venezuela[edit | edit source]

On January 3, 2026, the US launched military strikes on Venezuela in the early morning, targeting both military sites and civilian infrastructure. Caracas, the capital city, as well as the states of Miranda, Aragua and La-Guaira, were bombed, causing temporary electricity disruptions.[74] During the attack, roughly 150 aircraft were circulating, including AH-64 Apache and CH-47 Chinook helicopters and EA-18 Growlers equipped with electronic warfare systems such as Next-Gen Jammers.[52] As of January 4, the death toll of the attacks was reported as 80, though a Venezuelan official noted it may be higher.[75] As of January 7, Venezuelan Interior Minister Diosdado Cabello reported that the death toll of the attack had risen to 100.[48][76] Western media outlets have reported seven US soldiers injured.[77]

The attacks destroyed five research centers of the Venezuelan Institute for Scientific Research (IVIC), including the Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry, Ecology and the Nuclear Technology Units. Venezuela's Minister of Science and Technology, Gabriela Jiménez Ramírez, noted that these facilities were necessary for training professionals "who sustain our health, engineering and oil sovereignty."[49] The attacks also targeted medical supply warehouses in La Guaira, affecting 16,000 kidney patients who receive dialysis and nephrology supplies through the Venezuelan Institute of Social Security (IVSS).[50] It was reported that three months' worth of medicines for the renal patients had been lost due to the attacks.[51] An apartment building in Catia La Mar, La Guaira was also affected by the bombing.[78][79]

The location of Nicolás Maduro, the current president, was initially unknown for a time after the attacks began, while U.S. president Donald Trump claimed taking him and his wife, Cilia Flores, hostage.[80][81] It was later reported that Maduro and Flores were taken to the USS Iwo Jima and then flown to the US to be put on trial in New York.[52] According to reports of the kidnapping, the US's Delta Force troops descended from helicopters targeting president Maduro and Cilia Flores' location, facing resistance from soldiers on the ground, but overwhelming them with firepower from the air resulting in the death of 24 Venezuelans and 32 Cubans.[52]

Following a decision by Venezuela's Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice, Vice President Delcy Rodríguez assumed the role of acting president.[82]

In a press conference on January 3, US President Donald Trump remarked that "the oil business in Venezuela has been a bust, a total bust for a long period of time" and spoke on his intention to have "our very large United States oil companies" go in to Venezuela and added, "we are ready to stage a second and much larger attack if we need to do so."[53]

Further reading[edit | edit source]

External links[edit | edit source]

- Ministry of Popular Power of the Office of the Presidency (Spanish: Ministerio del Poder Popular del Despacho de la Presidencia)

- Vice Presidency of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (Spanish: Vicepresidencia de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela)

- Ministry of People's Power for Foreign Affairs (Spanish: Ministerio del Poder Popular para Relaciones Exteriores)

- Ministry of Popular Power for Communes (Spanish: Ministerio del Poder Popular para las Comunas)

- Venezuelan Television (VTV) (Spanish: Venezolana de Televisión)

- Alba Ciudad 96.3 FM, radio station of the Ministry of Popular Power for Culture (Spanish: Ministerio del Poder Popular para la Cultura)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ "Constitución de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela" (15 December 1999). Archived from the original.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Vijay Prashad (2008). The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World: 'Caracas'. [PDF] The New Press. ISBN 9781595583420 [LG]

- ↑ https://pt.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Resolucoesdo3oCongressoPT.pdf

- ↑ "How did Venezuela change under Hugo Chávez?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2023-04-24.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Saheli Chowdhury (2023-12-01). "Essequibo and Other Border Issues: Venezuela’s Territorial Losses to Imperialist Powers Through the Centuries (Part 1)" Orinoco Tribune. Archived from the original on 2023-12-02.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Saheli Chowdhuri (2023-12-03). "Essequibo and Other Border Issues: Venezuela’s Territorial Losses to Imperialist Powers Through the Centuries (Part 2)" Orinoco Tribune. Archived from the original on 2023-12-04.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 "The Strategic Revolutionary Thought and Legacy of Hugo Chávez Ten Years After His Death" (2023-02-28). Tricontinental. Archived from the original on 2023-04-29.

- ↑ “Milestones: 1866–1898 - Office of the Historian.” 2023. State.gov. 2023.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Wilkins, Brett. “The History - and Hypocrisy - of US Meddling in Venezuela.” Telesurenglish.net. teleSUR. 2018. Archived 2023-03-07.

- ↑ "US Imperialism in Nicaragua and the Making of Sandino" (2020-02-21). Archived from the original on 2021-03-05. Retrieved 2022-06-25.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 "Venezuela’s Caracazo: State Repression and Neoliberal Misrule" (2016-03-01). Venezuelanalysis. Archived from the original on 2025-12-10.

- ↑ "Luis Herrera Campins, 82; former lawmaker, president of Venezuela" (2007-11-10). Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Alan MacLeod (2018). Bad News from Venezuela: Twenty Years of Fake News and Misreporting: 'Introduction'. Routledge.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 James Suggett (2009-10-01). "Venezuela Advances Investigations of Fourth Republic Massacres" Venezuelanalysis. Archived from the original on 2025-11-09.

- ↑ https://www.mintpressnews.com/bolivarianism-vs-fake-us-democracy/38258/

- ↑ https://www.telesurenglish.net/news/Venezuelan-Government-Has-Built-4.2-Million-Homes-So-Far-20221028-0002.html

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Larry Elliott (2007-05-02). "Venezuela seizes foreign oil fields" The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2026-01-03.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Ben Norton (2025-12-19). "Trump admits he wants to take Venezuela’s oil – and give it to US corporations" Geopolitical Economy Report. Archived from the original on 2025-12-23.

- ↑ Ewan Robertson (2013-04-16). "Maduro Proclaimed Venezuelan President Elect Amid Opposition Claims of “Illegitimacy”" Venezuelanalysis. Archived from the original on 2026-01-20.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 George Ciccariello-Maher (2016). Building The Commune: Radical Democracy In Venezuela: 'Chapter 3: Counterrevolution'.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 “While some in Washington foreign policy circles may attempt to portray the leaders of this new wave of protests as persecuted pro-democracy heroes, they in fact have histories of supporting anti-democratic and unconstitutional efforts to oust the government. Both Leopoldo López and Maria Corina Machado supported the 2002 coup; in López’s case he participated in it by supervising the arrest of then-Minister of Justice and the Interior Ramón Rodríguez Chacín, when López was mayor of Chacao. Police dragged Rodríguez Chacín out of the building where he had sought refuge into an angry mob, who physically attacked him. Corina Machado notably was present when the coup government of Pedro Carmona was sworn in, and signed the infamous “Carmona decree” dissolving the congress, the constitution and the Supreme Court. [...] Venezuela’s opposition receives funding from U.S. “democracy promotion” groups including the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and core grantees such as the International Republican Institute (IRI) and the National Democratic Institute (NDI). The NED, which the Washington Post noted was set up to conduct activities “much of” which “[t]he CIA used to fund covertly” has made a number of grants directed at empowering youth and students in Venezuela in recent years, and USAID has also given money to IRI, NDI and other groups for Venezuela programs.”

"Violent Protests in Venezuela Fit a Pattern" (2014-02-19). Center for Economic and Policy Research. Archived from the original on 2025-04-27. - ↑ “Leopoldo Lopez Mendoza, a Harvard-trained politician and ardent opponent of Venezuela's socialist government, is seen by enemies and supporters alike as the face of recent street protests against the regime. [...] A child of privilege, Lopez was schooled largely in the United States, first at the elite Kenyon College in Ohio, before getting a master's degree at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government. [...] Maduro has accused "right wing fascists" -- of whom he considers Lopez the ringleader -- for the recent unrest. Lopez and two other opposition leaders -- deputy Maria Corina Machado and the mayor of metropolitan Caracas, Antonio Ledezma -- advocate using street protests to force Maduro from office.”

Patricia CLAREMBAUX (2014-02-18). "Leopoldo Lopez: Venezuela blueblood, ardent Maduro foe" AFP/Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on 2014-10-14. - ↑ "Venezuela" (2013-11-01). National Endowment for Democracy. Archived from the original on 2026-01-20.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 “In the past year, the United States channeled hundreds of thousands of dollars in grants to American and Venezuelan groups opposed to President Hugo Chávez, including the labor group whose protests led to the Venezuelan president's brief ouster this month. The funds were provided by the National Endowment for Democracy, a nonprofit agency created and financed by Congress. As conditions deteriorated in Venezuela and Mr. Chávez clashed with various business, labor and media groups, the endowment stepped up its assistance, quadrupling its budget for Venezuela to more than $877,000.”

Christopher Marquis (2002-04-25). "U.S. Bankrolling Is Under Scrutiny for Ties to Chávez Ouster" The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2025-12-08. - ↑ Roberto Lovato (2014-03-14). "Fauxccupy: The Selling and Buying of the Venezuelan Opposition" Venezuelanalysis. Archived from the original on 2025-06-24.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "FACT SHEET: Venezuela Executive Order" (2015-03-09). The White House. Archived from the original on 2025-12-01.

- ↑ Ben Norton (2025-11-15). "What is really happening in Venezuela? US attacks and economic situation explained" Geopolitical Economy Report. Archived from the original on 2025-11-25.

- ↑ Peru Will no Longer Support Blockade on Venezuela

- ↑ Blockade Against Venezuela Makes US Businesses Suffer: US Exports Dropped by 93% from 2012 to 2020 by Orinoco Tribune

- ↑ Andrew Buncombe (2019-04-26). "US sanctions on Venezuela responsible for 'tens of thousands' of deaths, claims new report" Independent. Archived from the original on 2022-02-19. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

- ↑ Venezuela Protesters Set 40 Tons of Subsidized Food on Fire (2017-06-30). TeleSur. Archived from the original on 2018-05-14.

- ↑ Venezuela's Economic War: Tons of Food Found Buried Underground (2015-08-17). TeleSur. Archived from the original on 2015-09-26.

- ↑ Food and Agriculture Organization. "Prevalence of undernourishment (% of population)" World Bank. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- ↑ Venezuela at UN: We must build 'new world without imperialism' by Ben Norton of Moderate Rebels on Substack Sep 22, 2021

- ↑ Carter Center > Venezuela > Monitoring Elections

- ↑ Roger G. Hood. The death penalty: a worldwide perspective, Oxford University Press, 2002. p10

- ↑ Determinants of the death penalty: a comparative study of the world, Carsten Anckar, Routledge, 2004, ISBN 0-415-33398, p.17

- ↑ Venezuela’s Strange Dictatorship by Orinoco Tribune

- ↑ Francisco Dominguez (2022-06-01). "MADURO’S SUCCESS: PRINCIPLED RESISTANCE TO IMPERIALISM PAYS OFF" Morning Star, Popular Resistance.

- ↑ "Ven App: Venezuela’s New Social Media" (2022-03-27).

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 41.4 41.5 41.6 Ben Finley, Konstantin Toropin, Regina Garcia Cano (2025-12-06). "A timeline of the US military's buildup near Venezuela and attacks on alleged drug-smuggling boats" MSN.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 "US Forces Destroy Small ‘Venezuelan’ Boat Allegedly Carrying Drugs—11 Killed" (2025-09-02). Orinoco Tribune. Archived from the original on 2025-09-13.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Nick Turse (2026-01-08). "After Undercounting Boat Strike Killings, U.S. Military Updates Death Toll" The Intercept.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 44.5 "Trump Claims Impending Seizure of 50 Million Barrels of Venezuela’s Oil Amid Continued Maritime Piracy (+Greenland)" (2026-01-08). Orinoco Tribune.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "Venezuela Launches Military Exercises in All Regions Throughout the Country" (2025-09-21). Orinoco Tribune. Archived from the original on 2025-10-17.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 "Venezuela: Militia Swells to 8 Million, International Supporters Pledge to Join" (2025-09-17). Orinoco Tribune. Archived from the original on 2025-10-21.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Ria Evelyn (2025-11-04). "Interview: Venezuela’s Militias and the Civil-Military Union" Venezuelanalys. Archived from the original on 2025-11-11.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 "Venezuela’s Interior Minister Cabello Updates Death Toll of US Military Attacks; President Maduro Liberation Committee Created" (2026-01-09). Orinoco Tribune.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 "Ataque criminal de EE.UU. destruyó instalaciones del IVIC" (2026-01-07). El Ministerio del Poder Popular para Ciencia y Tecnología.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Yusleny Morales (2026-01-07). "US attack on Venezuela affects 16.000 kidney patients" Últimas Noticias.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Ricardo Vaz (2026-01-06). "Venezuela: Brazil to Send Medical Aid Following US Bombings" Venezuelanalysis.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 Vijay Prashad and Carlos Ron (2026-01-07). "The current situation in Venezuela: a government in charge, a people resilient" Peoples Dispatch.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 The White House (2026-01-03). "President Trump Holds a Press Conference, Jan. 3, 2026". YouTube. Quote @ 53:50: "As everyone knows, the oil business in Venezuela has been a bust, a total bust for a long period of time. They were pumping almost nothing by comparison to what they could have been pumping and what could have taken place. We're going to have our very large United States oil companies, the biggest anywhere in the world, go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure, the oil infrastructure, and start making money for the country. And we are ready to stage a second and much larger attack if we need to do so."

- ↑ "Trump amenaza a Colombia, Cuba, Groenlandia, Irán y México tras el ataque estadounidense contra Venezuela" (2026-01-05). Democracy Now!.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Brett Wilkins (2026-01-20). "Trump ‘Piracy’ Continues as US Hijacks 7th Venezuela-Linked Oil Tanker" Common Dreams.

- ↑ Benjamin Norton (2022-02-06). "CIA backed failed 2020 invasion of Venezuela, top coup-plotter says" Multipolarista.

- ↑ https://elpais.com/diario/2002/04/17/internacional/1018994403_850215.html

- ↑ https://www.rt.com/usa/497111-trump-ruined-venezuela-coup/

- ↑ Dan Beeton (2022-04-20). "The Venezuela Coup, 20 Years Later" Venezuelanalysis.

- ↑ Michael Fox (2025-04-11). "Venezuela, 2002: When the people overturned a coup" The Real News Network. Archived from the original on 2025-05-03.

- ↑ George Ciccariello-Maher (2016). Building The Commune: Radical Democracy In Venezuela. Verso Books.

- ↑ Joe Parkin Daniels (2018-08-05). "Venezuela's Nicolás Maduro survives apparent assassination attempt" The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2022-07-15. Retrieved 2022-07-15.

- ↑ “Shortly after the drone attack, during an unrelated meeting on August 15, Venezuela came up, and Trump said to me emphatically, “Get it done," meaning get rid of the Maduro regime. “This is the fifth time I've asked for it,” he continued. I described the thinking we were doing, in a meeting now slimmed down to just Kelly and me, but Trump insisted he wanted military options for Venezuela and then keep it because “it's really part of the United States.””

John Bolton (2020). The Room Where It Happened: A White House Memoir: 'Chapter 9: Venezuela Libre'. Simon and Schuster. - ↑ Eugene Puryear (2017-10-11). "Is Venezuela Turning Further Left?" Liberation School. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22. Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- ↑ “We find that the sanctions have inflicted, and increasingly inflict, very serious harm to human life and health, including an estimated more than 40,000 deaths from 2017–2018; and that these sanctions would fit the definition of collective punishment of the civilian population as described in both the Geneva and Hague international conventions, to which the US is a signatory. They are also illegal under international law and treaties which the US has signed, and would appear to violate US law as well.”

Mark Weisbrot and Jeffrey Sachs (2019-04). "Economic Sanctions as Collective Punishment: The Case of Venezuela" Center for Economic and Policy Research. Archived from the original on 2025-08-13. - ↑ 66.0 66.1 "PSL Editorial – End the U.S. economic war on Venezuela now!" (2022-11-28). Liberation News. Archived from the original on 2023-01-27.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 Clare Ribando Seelke (2025-12-05). "Venezuela: Overview of U.S. Sanctions Policy" Congressional Research Service. Archived from the original on 2025-12-23.

- ↑ Justin Podur and Joe Emersberger (2021). Extraordinary Threat: The U.S. Empire, The Media, And Twenty Years Of Coup Attempts In Venezuela. Monthly Review Press.

- ↑ Alena Douhan (2021-09-06). "Report of the Special Rapporteur on the negative impact of unilateral coercive measures on the enjoyment of human rights, Alena Douhan - Visit to the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (A/HRC/48/59/Add.2) (Advance unedited version)" Reliefweb. Archived from the original on 2021-09-19.

- ↑ “President Donald Trump confirmed Wednesday that he has authorized the CIA to conduct covert operations inside Venezuela and said he was weighing carrying out land operations on the country. [...] Asked during an event in the Oval Office on Wednesday why he had authorized the CIA to take action in Venezuela, Trump affirmed he had made the move. “I authorized for two reasons, really,” Trump replied. “No. 1, they have emptied their prisons into the United States of America,” he said. “And the other thing, the drugs, we have a lot of drugs coming in from Venezuela, and a lot of the Venezuelan drugs come in through the sea.” Trump added the administration “is looking at land” as it considers further strikes in the region. He declined to say whether the CIA has authority to take action against President Nicolás Maduro.”

Aamer Madhani (2025-10-17). "Trump confirms the CIA is conducting covert operations inside Venezuela" AP. Archived from the original on 2025-12-17. - ↑ 71.0 71.1 "Venezuela: UN Report Demonstrates Illegality of US Blockade" (2025-12-27). Orinoco Tribune.

- ↑ Idrees Ali & Phil Stewart (2026-01-09). "US seizes fifth tanker as military stalks the ocean for Venezuelan oil" The Independent.

- ↑ "Southern Command Seizes Oil Tanker in New Act of Piracy" (2026-01-16). Orinoco Tribune.

- ↑ "US Strikes On Venezuela: What's Known So Far" (2026-01-03). Sputnik.

- ↑ "US attack on Venezuela: Death toll rises to 80 civilians and military personnel" (2026-01-04). Middle East Eye.

- ↑ "Cien personas asesinadas dejó ataque de Estados Unidos, informó Diosdado Cabello" (2026-01-08). AlbaCiudad.

- ↑ Victor Loh (2026-01-07). "Seven U.S. troops injured in Venezuela raid that captured Maduro, Pentagon says" CNBC.

- ↑ Yuleidys Hernández Toledo (2026-01-04). "Así atacó Estados Unidos al pueblo venezolano (+Fotos y videos)" Alba Ciudad. Archived from the original on 2026-01-05.

- ↑ "Destrozos provocados por el bombardeo asesino del gobierno de los Estados Unidos de América a edificaciones multifamiliares en el sector “La Soublette”, pquia Catia la Mar, estado La Guaira. Este es el resultado de la prédica anti nacional de la derecha fascista y de la política de cambio de régimen del imperialismo que quiere adueñarse de nuestros recursos naturales y esclavizar a nuestro pueblo. No han podido ni podrán, nosotros venceremos." @eduardopsuv, Instagram, 2026-01-04.

- ↑ @SputnikInt (2026-01-03). "🚨🇺🇸🇻🇪 Donald Trump confirms the US carried out strikes on Venezuela, claims Maduro and his wife were captured" Twitter/X.

- ↑ "Trump Says Venezuela's Maduro Captured After Strikes" (2026-01-03). Reuters.

- ↑ "Venezuela: Supreme Court Directs Vice President Delcy Rodríguez to Assume Presidency of the Republic" (2026-01-04). Orinoco Tribune.