More languages

More actions

| Antigua and Barbuda Wadadli–Wa’omoni | |

|---|---|

| 1860 | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | St. John's |

| Common languages | Antiguan and Barbudan Creole English |

| Dominant mode of production | Capitalism |

| Government | Parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Charles III |

• Prime Minister | Gaston Browne |

| Area | |

• Total | 440 km² |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | 104,000 |

Antigua and Barbuda is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the Caribbean. It is a former colony of the British, and retains the British Monarch, Charles III, as its head of state.[1]

History[edit | edit source]

Pre-colonization[edit | edit source]

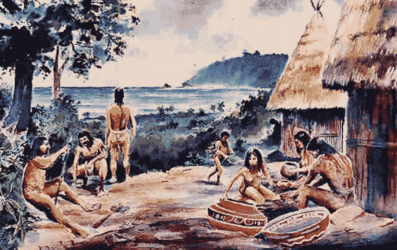

People have lived on Antigua since around 3000 BC; evidence of early settlements has been found near the modern-day town of Parham. On Barbuda, a Stone-Age site dating to 1875 BC was discovered near the former Spanish fort, Martello Tower. The people who inhabited this area at the time of European contact are known as the Island Caribs, who were a blend of two Amerindian groups: the Arawaks and the Caribs.[2]

Before the Arawaks, the Archaic peoples (sometimes historically called Ciboney) were the earliest known inhabitants of the two islands. "Ciboney" translates to "stone people" in the Arawak language. These Archaic peoples were excellent craftsmen, creating jewelry from shells and leaving many artifacts across the islands. They eventually mixed with the Arawaks and later the Caribs to form the Island Caribs.[2]

Indigenous Island Carib society was built upon a form of primitive communism - subsistence system. These communities operated within a framework of communal ownership and cooperative labor, where food was produced to be consumed and shared to ensure the entire community was fed. They were primarily subsistence farmers who also made pottery and cultivated a variety of crops, including pineapples, cotton, and peanuts. Their most important crop, however, was the cassava root.[3]

The Arawaks introduced intensive agriculture, as well as crops like corn, tobacco, cotton, chili peppers, and black pineapples. They established fishing villages and introduced an architectural style designed to harvest rainwater more efficiently using tall roofs. They also introduced advanced boat-building to the region and had dedicated villages for this craft, as fishing was a major food source.[2]

Cassava played such an important role in their society that they not only created cassava bread as a staple food, a process that involved removing its poisonous juice through a woven tipiti tube to create flour, but their supreme god, Yocahu, was also affiliated with the crop.[2]

The Arawaks were expert canoe builders who constructed massive dugout canoes capable of carrying 70 or more people for trade with other islands and for travel. Historical records indicate that they also used montones, a technique involving mounds of soil to improve drainage and soil quality, along with various irrigation systems.[4]

Island Carib men wore their hair long and occasionally wore aprons; though they were often nude, they did adorn themselves with sea-shell jewelry. They were polytheistic, worshipping three primary gods: a main supreme god and two lesser deities. Their supreme god was Yocahu. The other two were Atabeyra, the goddess of fertility, and Opiyel Wa'obiran, the god of death, who took the form of a dog.[4]

Most of the Island Caribs were killed by European diseases, such as smallpox and influenza. Those who survived were often massacred by English and French settlers, while others were enslaved and ultimately absorbed into the population of African slaves brought to the islands by British colonists.[2]

Even before the English and French settlers began their genocide against the natives, the Spanish had launched slave raids from Hispaniola (the island now shared by the Dominican Republic and Haiti). These raids captured and enslaved the Island Caribs, forcing them to work in mines and plantations. This led to significant depopulation, which made the subsequent genocide committed by the English and French settlers easier.[5]

The English settlers, after cleansing the island of the Caribs around 1632, intended to use the land for sugar plantations and then later on brought the African slaves over to the island to tend to the sugar plantations. Antigua and Barbuda were called Waladli and Wa’omoni by the Island Caribs. Waladli is still used by locals today.[2]

Colonization[edit | edit source]

Christopher Columbus was the first European to sight the islands in 1493, naming one of them Santa Maria de la Antigua after a church in Seville, Spain. Initial colonization attempts failed due to raids and attacks by the Arawak people. The first successful European settlement was established by the English, who arrived from the Caribbean island of St. Kitts in 1632.[6]

Due to previous Spanish slave raids that had left the island depopulated and weakened, the English were able to carry out a genocide against the remaining Island Caribs. The few surviving Caribs mixed with the growing population of African slaves, which explains the absence of historical references to the Caribs after 1705.[2]

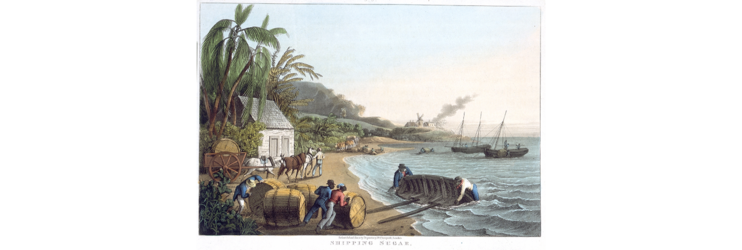

Following this, the English began establishing settlements and plantations. Tobacco and sugar were the primary crops, though tobacco was eventually abandoned due to its detrimental effect on the soil. From the outset, the plan involved importing enslaved people from West Africa to work the plantations. As sugar cane became increasingly vital to the British Empire, there was a strong incentive to expand these operations. This led to the massive importation of slaves, who soon vastly outnumbered the European settlers.[7]

Because of the economic importance of the sugar plantations, the English needed to protect them from French and Spanish attacks. The British Navy established English Harbor in Antigua and built numerous forts around the islands. However, the resources devoted to these defenses and the ongoing threat of attack meant that enslaved Africans faced increasingly brutal conditions. One common punishment was to tie people to a tree known as the "agony tree",a tree covered in sharp spikes, where they were whipped. The tree's sap could cause blindness if it made contact with the eyes.[2]

Enslaved people were forced to work without protective gear near sugar-cane mills, where the heavy rollers sometimes crushed their limbs, losing their arms. Others were forced to labor in intensely hot boiling houses, removing impurities from the sugar.[2]

Some slave masters also forced enslaved people to place torches near the reefs of Barbuda to trick passing ships. Captains would mistake the lights for safe landing points and steer toward them, causing the ships to crash on the reefs. The masters would then order the enslaved people to loot the wrecked ships. Since slaves were viewed as expendable, the masters considered the loss of a few lives an acceptable cost for this practice, which served as a source of extra income alongside hunting and the sugar plantations.[2]

Throughout the era of slavery, numerous uprisings occurred on both islands due to the brutal conditions imposed by the British. Major revolts took place in 1701 and 1729, and a series of rebellions were organized between 1741 and 1835. In 1834, when the British attempted to transport slaves from Barbuda to Antigua, the enslaved people rebelled, took control of Barbuda, and established a system of communal land ownership.[8]

Even after the abolition of slavery, many were forced into wage labor to survive. They continued to live in the same small huts as before, working for low pay and with no rights. Black workers could be jailed or whipped for minor offenses. Even more disturbingly, there was a pattern of murders of Black workers that went systematically unpunished due to a lack of investigation on purpose.[2]

Riots and protests were met with violence, and police would shoot Black working-class demonstrators on the spot. This climate of terror taught Black workers that demanding better treatment led to the murder of themselves and their families.[9]

-

The slaves fight back against their oppresive masters.

Independence & Neo-colonialism[edit | edit source]

In 1981 Antigua and Barbuda were granted independence from the United Kingdom leading to a politically dominant Antigua as the island holds over 95% of the nations population.

Because the entire island of Barbuda had been held under a single land grant, the community continued the practice of autonomous cultivation on communal land in the post-emancipation era. All Barbudans shared equally in the ownership of the land and had access to it for individual cultivation under the authority of the local government. Until recent times, this system protected the land from being sold to foreigners and preserved the island’s cultural heritage.[10]

In fact, several attempts to impose different land practices, including the privatization of land plots, failed repeatedly after emancipation and throughout the 20th century. However, the situation took a sharp turn in 2017 when Hurricane Irma devastated the island, destroying property and devastating its ecology and environment. For the first time in 400 years, the people of Barbuda were forced to evacuate their land.[11]

This forced expulsion created an opportunity for the government of Antigua and Barbuda, which it seized in the wake of the hurricane's devastation. The government wasted no time in manipulating the terms of return and politicizing the recovery process. Because Barbudans lacked the funds to rebuild, their land became a commodity to be sold and corrupted. The government passed the Barbuda Land Amendment Act of 2017, which ended the system of communal land ownership. This Act forced the people of Barbuda, who have fought for and lived on the land for generations,to purchase it from the government, a price they could not afford due to widespread poverty.[12]

Even before the hurricane, the island's population suffered from food insecurity, poor water quality, high poverty and unemployment rates, and extreme brain drain as educated citizens left for better opportunities. Fishing, once a means of ensuring food security, had already declined due to coral reef bleaching and death, which led to the depletion of fish stocks.[13]

After the Category 5 megastorm hit, foreign multinational developers and the Antiguan government actively perpetuated the destruction by funneling money into tourist ventures while the Barbudan people were devastated. Prime Minister Gaston Browne not only ignored the pleas of the Barbudans but also, while their lives and property were in ruins, convinced them to sell their land. This was a direct violation of the 2007 Barbuda Land Act, which explicitly stated: "No land in Barbuda shall be sold."[14]

While the people were struggling to recover from the disaster, those already grappling with food insecurity and poverty were asked by their prime minister, who had failed to aid them at all, to give up their land for tourist development.[14]

In 2018, the repeal of the Barbuda Land Act was passed, enabling the government to sell Barbudan land without consulting its people. Immediately, wealthy foreign investors bought up swathes of the previously communal land under the guise of being benevolent saviors. Soon after, the Barbudans, who had been evacuated to Antigua, were prevented by the military from returning to their island. The government claimed this was due to health concerns.[15]

Family dogs that had been left behind and formed starving packs were killed by the military, and livestock starved. Not long after, construction began on gated communities, hotels, marinas, a large airport, and golf courses over the ruins of Barbuda, all for tourists.[16]

Despite the atrocities, there is a growing resistance movement called "Barbuda Silent No More," which amplifies the struggles of the Barbudan people. This event remains a stark example of neocolonialism and a side-effect of a capitalist world order where profit trumps all. [1]

In 2019, Prime Minister Browne demanded reparations from Harvard University, which received hundreds of acres of land from the Codringtons.[9]

Economy[edit | edit source]

Antigua and Barbuda's economy relies on oil exports and tourism from the Global North. 82% of workers in Antigua and Barbuda work in the service industry.[9]

Grants flowing into the Antiguan and Barbudan economy have declined, largely replaced by loans. This shift is evident in the surge of personal loans, which leaped from EC$125.2 million in 1985 to $215.3 million in 1989 without a corresponding increase in productive capacity.[17]

This lack of growth is mirrored in the nation's trade balance. In 1988, Antigua’s exports amounted to only EC$82.1 million, while imports reached a staggering EC$815.7 million, a trade deficit of $733.6 million. From 1985 to 1988, imports rose from $518 million to $815.7 million, while exports declined from $83.4 million to $82.1 million.[17]

To bridge such gaps, countries often turn to international lenders. The World Bank and the IMF lend money globally, and these loans frequently have crippling side-effects for developing economies. In Antigua and Barbuda, a significant portion of IMF funding ends up in the pockets of unproductive government bureaucrats. Furthermore, the loan conditions imposed by these institutions often force elected officials to enact harmful policies. For example, in Nigeria, the IMF compelled the government to remove a crucial petrol subsidy and increase fuel prices to be more "competitive" on the international market, a move that severely burdened the poor.[18]

This pattern is regrettably common across the Global South. Corrupt officials enrich themselves with international loans while implementing policies that devalue their national currencies and sacrifice their economies for personal gain.[18]

Compounding these issues is Antigua and Barbuda's narrow economic focus. Since emancipation, and especially since the 1980s, the economy has fully pivoted towards tourism at the expense of productive sectors like agriculture and manufacturing. While fishing registered an increase of approximately 60%, the contribution of livestock and agricultural exports fell to a level lower than at the start of the decade.[19]

An economy cannot rely solely on tourism indefinitely without a supportive industrial base, whether service-oriented or hard-industry based. The islands will soon reach their physical and social capacity for tourists. Consequently, the combination of a tourism-dependent economy and the neo-colonialist pressures of 21st-century financial institutions like the IMF and World Bank creates a dangerous future for the nation.[19]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Dr. Matthew Quest (2018-06-13). "Enclosure, Dispossession and Disaster Capitalism in Antigua and Barbuda" Black Agenda Report. Retrieved 2023-12-31.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Sara Louise Kras (2008). Antigua and Barbuda: '23'.

- ↑ Embassy of Antigua and Barbuda (2020-03-03). "History of Antigua and Barbuda" Antigua and Barbuda’s Embassy in Madrid.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Charles Cobb. "Taíno Culture History" Florida Museum.

- ↑ David Wheat (2019-04-29). War and Rescate: The Sixteenth-Century Circum-Caribbean Indigenous Slave Trade.

- ↑ The National Archives of Antigua and Barbuda. "Antigua" Lancaster University.

- ↑ Barbados National Commission for UNESCO (2014/12/02). "The Industrial Heritage of Barbados: The Story of Sugar and Rum" UNESCO.

- ↑ Mike Dash (2013-01-02). "Antigua’s Disputed Slave Conspiracy of 1736" Smithsonian magazine.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Matsemala Odom (2021-03-15). "Africans in Antigua and Barbuda fight for land, demand reparations" The Burning Spear. Archived from the original on 2021-06-13. Retrieved 2022-08-13.

- ↑ Antigua and Barbuda Gazette, pp. 1-18 (16/09/2007). "Barbuda Land Act, 2007 (No. 23 of 2007)" United Nations Environment Programme - Law and Environmental Assistance Platform.

- ↑ Kenneth Mohammed (2023-09-06). "‘Billionaire club’: the tiny island of Barbuda braces for decision on land rights and nature" The Guardian.

- ↑ Sophia Perdikaris (2021). Disrupted Identities and Forced Nomads: A Post-Disaster Legacy of Neocolonialism in the Island of Barbuda, Lesser Antilles.

- ↑ Tiara Tyson (2021-08-19). "Improving Food Security in Antigua and Barbuda" The Borgen Project.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Antigua and Barbuda: Barbudans Fighting for Land Rights" (2018-07-12). Human Rights Watch.

- ↑ ECOLEX (2018-01-22). "Crown Lands (Regulation) (Amendment) Act No. 6 of 2018." InforMEA.

- ↑ "This Caribbean Island Was Evacuated After Irma. Now, the Pets Left Behind Are Going Feral". TIME Magazine.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 IMF (1997). Antigua and Barbuda: Recent Economic Developments - ISCR/98/7. [PDF]

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Glen Biglaiser. The effects of IMF loan conditions on poverty in the developing world.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Dr. Allan N. Williams (2003-02-05). Antigua & Barbuda COUNTRY EXPERIENCE. [PDF]