More languages

More actions

State of California | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

| |

| Capital | Sacramento |

| Largest city | Los Angeles |

| Area | |

• Total | 423,970 km² |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 39,185,605 |

California is a state within the United States of America. Its population and economy is among the largest in the USA.[1]

Over 500 Native American tribes have lived in the area, and, prior to colonization, a minimum of 100 different languages were spoken among them.[2] In contrast to reservation-based groups, many California native groups never received federal acknowledgment from the U.S. settler-state. Native Californians continue to live throughout the state, with or without federal recognition.

The United Farm Workers labor union was founded in California in 1962. California is also the location of the founding of the Black Panther Party, which was formed in the city of Oakland in 1966.

Ronald Reagan, 40th president of the United States, was the Governor of California from 1967 to 1975.

According to the Prison Policy Initiative, California has an incarceration rate of 549 per 100,000 people (including prisons, jails, immigration detention, and juvenile justice facilities). The Initiative notes that California, similar to other individual U.S. states, "locks up a higher percentage of its people than almost any democracy on earth."[3][4] In the 1940s, California provided the first of several detention camps for the forced relocation and internment of Japanese Americans.[5] A dungeon at San Quentin State Prison, dating to 1854, is thought to be California's oldest surviving state-constructed building.[6]

California is the location of the California genocide, in which the California settler-state and federal authorities incited, aided, and financed violence, murder, and slavery against the Native Californians, engaging in this campaign most intensely during the 1800s.[7][8]

History[edit | edit source]

Early history[edit | edit source]

The earliest human occupation in the area of the state dates back 19 thousand years. The Indigenous peoples of California spoke a minimum of a hundred different languages at the time, had their own specific food cultures, and distinct religious beliefs. In the late 18th century, over 300,000 people were living in the state.[2]

The peoples living in the California culture area at the time of first European contact in the 16th century were only generally circumscribed by the present state boundaries. Some were culturally intimate with peoples from neighboring areas; for instance, California groups living in the Colorado River valley, such as the Mojave and Quechan (Yuma), shared traditions with the Southwest Indians, while those of the Sierra Nevada, such as the Washoe, shared traditions with the Great Basin Indians, and many northern California groups shared traditions with the Northwest Coast Indians. Most California groups included professional traders who traveled long distances among the many tribes; goods from as far away as Arizona and New Mexico could be found among California’s coastal peoples. Except for the Colorado River peoples (Mojave and Quechan) and perhaps some Chumash groups, California peoples avoided centralized governmental structures at the tribal level; instead, each tribe consisted of several independent geopolitical units. These were tightly organized polities that nonetheless recognized cultural connections to the other polities within the tribe.[9]

Native Californians developed a variety of specialized technological devices to help them maximize the productivity of the region’s diverse environments. The Chumash of southern coastal California made seaworthy plank canoes from which they hunted large sea mammals. Peoples living on bays and lakes used tule rafts, while riverine groups had flat-bottom dugouts made by hollowing out large logs. Traditional food-preservation techniques included drying, hermetic sealing, and the leaching of those foods, notably acorns, that were high in acid content. Milling and grinding equipment was also common.[9]

Spanish colonization[edit | edit source]

From 1769 to 1800, the California coast was under Spanish control from San Francisco in the north to San Diego in the south. California was colonized by the Spanish beginning in 1769, when Junípero Serra and his successors began to build a series of missions along the region's southern Pacific Coast. The Spanish mission system was a method of colonization in the area that used religious doctrine heavily in its self-justification. Accompanied by soldiers and soon followed by ranchers and other colonial developers, Spanish missionaries initiated a long period of cultural rupture for most of California’s indigenous peoples. Native communities were often forcibly dislocated to missions, where they were made to work for the colonizers and to convert to Christianity.[9] The Spanish used Native Californian's labor to build the missions and abused, exploited, and murdered the people. Meanwhile, Native Californians consistently resisted Spanish rule.[10]

Spanish troops arrived in what is now San Francisco in 1776 and built their northernmost military outpost in America, the Presidio of San Francisco.[11]

Mexican rule[edit | edit source]

In 1821, Mexico gained its independence from Spain, and the Alta California region was designated as a territory of Mexico, its capital located in Monterrey, California. During this time, a number of Europeans and Statesians became naturalized Mexican citizens and settled in California.[citation needed] In 1842, the U.S. Navy invaded California and briefly captured Monterrey.[12]

U.S. colonization[edit | edit source]

In 1848, California came under the rule of the United States, which was soon followed by the California genocide, in which the California settler-state and federal authorities incited, aided, and financed violence against the Native Californians. The California Act for the Government and Protection of Indians was enacted in 1850 (amended 1860, repealed 1863). This law provided for "apprenticing" or indenturing Indian children to Whites, and also punished "vagrant" Indians by "hiring" them out to the highest bidder at a public auction if the Indian could not provide sufficient bond or bail, effectively legalizing a form of slavery targeting Native Californians.[7] Over the course of 25 years, the United States reduced the native Californian population from more than 130,000 to only 30,000.[13]

In An American genocide: the United States and the California Indian catastrophe, 1846-1873, author Benjamin Madley writes that the "organized destruction of California's Indian peoples under US rule was not a closely guarded secret" and that "California newspapers frequently addressed, and often encouraged, what we would now call genocide, as did some state and federal employees." Madley also quotes US Indian Affairs commissioner John Collier as saying, "The world's annals contain few comparable instances of swift depopulation—practically, of racial massacre—at the hands of a conquering race."[8]

In 1860, U.S. forces forced the Modoc people onto a reservation in southern Oregon. Kintpuash led a guerrilla resistance against General Edward Canby. At the Battle of Stronghold in January 1873, they defeated a detachment of 400 soldiers without a single Modoc casualty and killed Canby. Nevertheless, the genocidal U.S. invaders defeated the Modocs by April 1873 and scattered their descendants from Oregon to Oklahoma.[13]

In 1891, the state of California took over executions of prisoners from the state's individual counties and began carrying out death sentences at Folsom State Prison, east of Sacramento. San Quentin joined this practice two years later. A total of 215 “judicial hangings” were carried out on San Quentin’s gallows over the next 45 years.[14]

1900 to 1950s[edit | edit source]

California introduced a eugenics law in 1909 that forcibly sterilized 20,000 disabled people and inspired the Nazi eugenicist movement. Forced sterilizations continued into the 21st century and also targeted many imprisoned women.[15]

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, a mass migration event occurred, with many people from Oklahoma relocating in California in search of work opportunities. Between 1931 and 1933, 10 percent of Oklahoma farmers lost their land to foreclosure, and tenant farmers (who comprised more than 60 percent of Oklahoma farmers in the 1930s) had little incentive to endure poor crops and low prices year after year. During the decade of the Great Depression, Oklahoma faced a net loss through migration (outflow minus inflow) of 440,000. Although Oklahomans left for other states, they made the greatest impact on California and Arizona, where the term "Okie" came to denote any poverty-stricken migrant from the Southwest (Arkansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas). From 1935 to 1940 California received more than 250,000 migrants, and a plurality of the most impoverished migrants came from Oklahoma. Briefly in 1936 the Los Angeles police established a "'bum blockade'" at the California border to keep out these "undesirables".[16] According to Ruth Wilson Gilmore in Golden Gulag, "Dense relations among Filipino, Mexicano/Chicano, African, Chinese, and Japanese workers and labor contractors and their mostly Anglo employers took on new complexity when waves of Anglo Okies poured into the state in the later part of the depression, prompting inter-Anglo class and status strife."[17]

San Quentin became the state's sole designated prison for executions in 1938 when the state unveiled its new two-seater gas chamber, nicknamed “The Smokehouse” by those waiting to die.[14]

When the U.S. government ordered the forced relocation of thousands of Japanese Americans to detention camps during World War II, the first camp to go into operation was Manzanar, located in southern California.[5]

Gilmore writes that the "creative destruction" of World War II boosted the California and national economies out of depression, saying that California's military industry was large, consisting of both converted capacities and assembly lines developed specifically for production of war matériel, and that by 1940, the federal government was investing 10 percent of its spending in California, a state that comprised 7 percent of the nation. Millions, including several hundred thousand African Americans, moved to California to build war machines, and that this this economically prosperous period (1938–45) changed the state’s demographics, and particularly the racial structure of cities, as Black homeowners established communities in San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley, Richmond, and Los Angeles. According to Gilmore, in the postwar period, the repeal of de jure school segregation (1946) and the declaration that restrictive covenants on real property were unconstitutional (1948) provoked long-lasting pro-apartheid activism on the part of white Californians, and their their political activism culminated in a state constitutional amendment organized by the realtors’ association that guaranteed the right of home and other property owners to refuse to sell to anybody for any reason.[17] In other words, the discriminatory practice of redlining in California was strengthened by the efforts of the realtors' association in response to an influx of Black homeowners and the repeal of segregation laws during the 1940s in California.

Seeking investment via government contracts, California became increasingly involved in developing technology for the Department of Defense throughout the 1950s, primarily in the field of aerospace and electronics research and development. Throughout the Cold War, California developed major military-industrial districts, heavily concentrated in Los Angeles and Santa Clara (Silicon Valley) Counties. The massive infusion of wealth designated for aeronautical and electronic warfare innovations required a new and specialized labor force, prompting the state to make enormous investment in educational infrastructure.[17]

1960s and 70s[edit | edit source]

By the 1960s, African Americans who had migrated to California from the South and East due to the wartime manufacturing jobs were poorer in real terms in 1969 than they had been in 1945, because after the Second World War ended, most were pushed out of war manufacturing jobs, whose pay levels could not be duplicated in other sectors. This was one of the factors that contributed to extreme poverty concentrating in Alameda County, Los Angeles, and other regions where Black people had settled in California during the 1930s and 1940s.[17]

The 1965 Watts Rebellion was a response to inequality in Los Angeles, where everyday apartheid was forcibly renewed by police under the direction of the unabashedly white supremacist Chief William Parker. The Black Panther Party (BPP), originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, was founded in 1966 in Oakland, California, to defend the community against local police brutality.

The United Farm Workers labor union was founded in California in 1962.

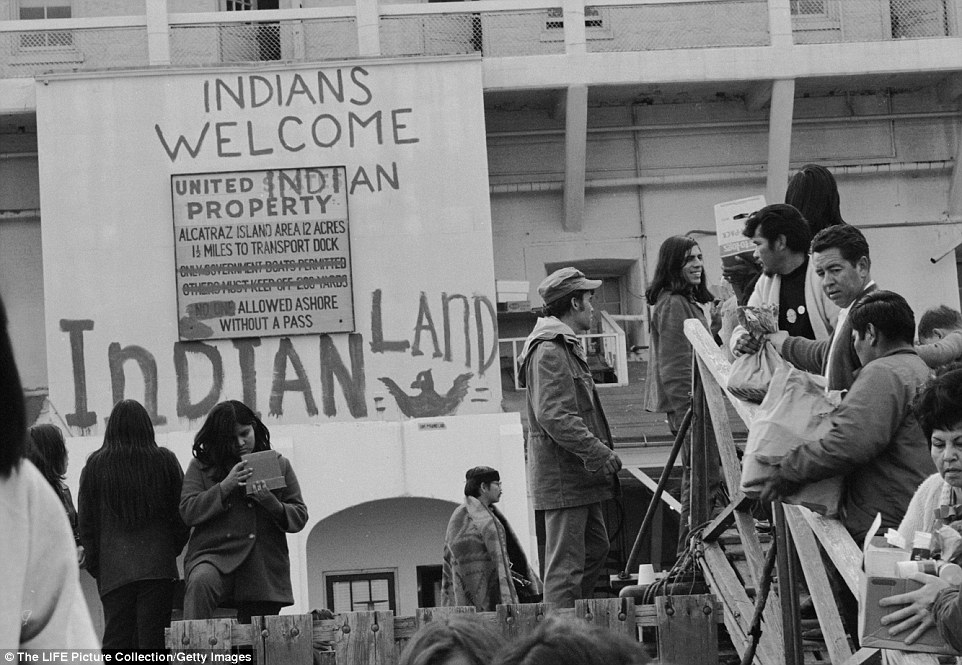

On March 9, 1964, five Sioux Indians occupied Alcatraz Island, location of Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary which had closed in 1963. They occupied for four hours, claiming it on the basis of the Sioux Treaty of 1868, which held that any surplus federal property would revert back to Native American ownership.[18]

A more extensive occupation occurred from November 20, 1969 to June 11, 1971, as Native American activists and their supporters occupied Alcatraz for 19 months, living on the island together until the government switched off electricity, water and telephone service and federal marshals arrived to remove the last of the occupiers.[19] In 1972, the National Park Service purchased Alcatraz along with Fort Mason from the U.S. Army to establish the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

The 1969–70 recession hit California harder than the rest of the United States because of deep cuts in military spending, and unemployment in the state nearly doubled. In agriculture, the drought of 1975–77 drove smaller farmers into bankruptcy.[17]

Ronald Reagan, 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989, was the Governor of California from 1967 to 1975.

1980s and 90s[edit | edit source]

Between 1980 and 1984, DOD prime contracts achieved new highs and California continued to command a disproportionate share of income from the trillion dollar arms buildup under the Carter and Reagan administrations, most of which went to higher-wage workers.[17]

On June 5, 1981 Michael Gottlieb, MD of the University of California, Los Angeles and others authored the first report identifying the appearance of diseases that would later become known as AIDS. In 1982, the San Francisco AIDS Foundation was founded.[20]

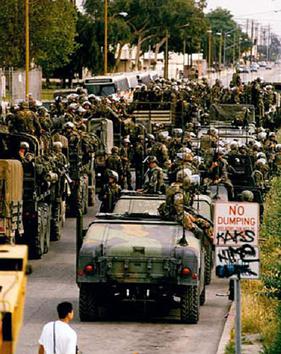

In 1992, the 1992 Los Angeles Uprising or 1992 Los Angeles Riots began. Unrest began in South Central Los Angeles on April 29, after a jury acquitted four officers of the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) charged with using excessive force in the arrest and beating of Rodney King. The verdict of the case of the killing of 15 year old girl Latasha Harlins by a convenience store owner also influenced the tensions leading up to the unrest. The uprising took place in several areas in the Los Angeles metropolitan area as thousands of people rioted over six days following the verdict announcement of the Rodney King case.

In 1994, anti-military protests forced the Pentagon to close its military base in San Francisco.[11]

2000s to present[edit | edit source]

California has carried out 10 executions by lethal injection, the most recent was in 2006.[14] In 2006, the state of California paid $853,000 for its new lethal injection chamber in San Quentin, which was intended to conform with modern court rulings on cruel and unusual punishment and to provide a more "humane" means of execution. However, the new lethal injection chamber has never been used and was decommissioned in 2019 when Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a moratorium on executions in the state.[14]

Geography and climate[edit | edit source]

California is the third-largest state in the United States in area, after Alaska and Texas. California is one of the most geographically diverse states in the U.S. California is commonly described as consisting of two major regions, Northern and Southern California. The California Central Valley runs along the middle of the state and is surrounded by various mountain ranges, including the Sierra Nevada mountains. The Central Valley is California's biggest center of agricultural production.

Northwestern California has a temperate climate, and the Central Valley has a Mediterranean climate but with greater temperature extremes than the coast. The high mountains, including the Sierra Nevada, have an alpine climate with snow in winter and mild to moderate heat in summer.

Almost all of southeastern California is arid, hot desert, with routine extreme high temperatures during the summer. The southeastern border of California with Arizona is entirely formed by the Colorado River, from which the southern part of the state gets about half of its water. In the south is a large inland salt lake, the Salton Sea. The south-central desert is called the Mojave; to the northeast of the Mojave lies Death Valley, which contains the lowest and hottest place in North America.

As part of the Ring of Fire, California is subject to tsunamis, floods, droughts, Santa Ana winds, wildfires, landslides on steep terrain, and has several volcanoes. It has many earthquakes due to several faults running through the state, the largest being the San Andreas Fault.

In Southern California, wildfires naturally occur during summer and fall, when dry weather removes most of the moisture from many plants and hot dry winds can spread any fires that ignite, including from natural sources of ignition, such as lightning. However, most fires are ignited by human activity. The largest fires occur in the summer during years of low rainfall and extended dry periods and in the fall during Santa Ana wind events.[21]

Political prisoners held in California[edit | edit source]

Current[edit | edit source]

Former[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ "California Population 2022" (2022). World Population Review. Retrieved 2022-8-13.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 “A Guide to California’s Tribes and Indigenous Peoples.” 2022. California.com. Retrieved 2022-08-14.

- ↑ Prison Policy Initiative. 2021. “California Profile.” Prisonpolicy.org.

- ↑ Prison Policy Initiative. 2021. “States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2021.” Prisonpolicy.org. Archived 2022-08-18.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 “Japanese American Internment | Definition, Camps, Locations, Conditions, & Facts | Britannica.” Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Brown, Patricia Leigh. San Quentin journal. Prison makes way for future, but preserves past. Archived 2015-10-19 at the Wayback Machine New York Times, January 18, 2008.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ojibwa (March 2, 2015). "California's War On Indians, 1850 to 1851". Native American Netroots.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Benjamin Madley (2016). An American genocide: the United States and the California Indian catastrophe, 1846-1873. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Lowell John Bean. "California Indian." Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ “Five Views: An Ethnic Historic Site Survey for California (American Indians).” 1988. Nps.gov. California Department of Parks and Recreation. Office of Historic Preservation.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 David Vine (2020). The United States of War: 'Going Global' (p. 171). Oakland: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520972070 [LG]

- ↑ David Vine (2020). The United States of War: 'The Permanent Indian Frontier' (p. 150). Oakland: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520972070 [LG]

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Stephanie Hedgecoke (2023-01-16). "Battle of Stronghold 1873: Indigenous Modoc people resisted" Workers World. Retrieved 2023-01-23.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Hardy, A.J. “The End of the Line for Death Row?” San Quentin News. Sanquentinnews.com. April 18, 2022. Archived 2022-08-18.

- ↑ Monica Moorehead (2023-01-20). "California’s heinous sterilization program" Workers World. Archived from the original on 2023-01-20. Retrieved 2023-01-23.

- ↑ Mullins, William H. “Okie Migrations | the Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.” Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived 2022-08-28.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. "Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California." University of California Press. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 2007.

- ↑ Kahle, Thomas. "Breaking Point: The 1969 American Indian Occupation of Alcatraz Island." Coe College. Penn History Review. Volume 26, Issue 2, Article 4. February 2020. Archived 2022-08-18.

- ↑ Leach, Naomi. “Idyllic Teepees at the US’s Most Notorious Prison: Fascinating Photos Reveal Life on the Rock in the late 1960s when Native Americans occupied Alcatraz” Daily Mail. November 15, 2016.

- ↑ “40 Years of AIDS: A Timeline of the Epidemic.” 2021. 40 Years of AIDS: A Timeline of the Epidemic | UC San Francisco. June 4, 2021. Archived 2022-08-18.

- ↑ “Climate, Fire, and Habitat in Southern California - SAFER (Sustainable and FirE Resistant) Landscapes.” University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources. Ucanr.edu.