More languages

More actions

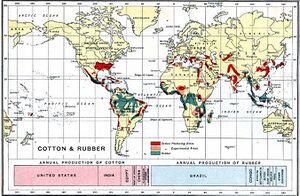

Natural rubber, often simply called rubber, is a material derived from latex, a liquid produced by some plants. The majority of natural rubber grown commercially is grown on rubber plantations in tropical regions. Rubber plantations worldwide mainly obtain latex from the Hevea brasilensis tree, originally native to the Amazon basin of South America.[1][2] Today, the majority of natural rubber is produced in Southeast Asia, especially in Thailand, Indonesia, and Vietnam, though it is produced in several other countries as well.[3][4] Liberia, Côte d'Ivoire, and Laos are among the countries with the highest percentage of rubber composing their exports.[5]

About 60 to 70% of natural rubber produced is used for the production of vehicle tires.[6] Since World War II, synthetic rubbers derived from petroleum products have come into widespread use in addition to natural rubber.[2] However, natural rubber remains preferable for certain applications. For example, natural rubber, rather than synthetic rubber, is especially important for use in aircraft tires.[7]

Historically, access to natural rubber has been and continues to be strategically important due to its many applications, including its military uses.[8] A paper produced in 2024 for the United States Department of Homeland Security noted that any major interruption in rubber shipment would have major implications for the US economy and national security, and that "China is currently much better positioned to respond to any decline in supply than the United States", also noting that the US no longer has control over all resources necessary for synthetic rubber production, and recommended that the US begin stockpiling natural rubber, describing the US as at risk militarily and economically due to China's edge in natural rubber access.[9] The paper concludes, "Unless we take steps to adequately protect our market access, the U.S. risks a potential economic crisis, and we will not have the same tools that we had during World II to manage such a crisis" and that the result of inaction could be "catastrophic."[10] One of the strategic considerations of natural rubber is the time it takes for rubber trees to start producing latex, taking years to be ready for tapping[2][9] and reaching peak efficiency at 15 years.[2] Therefore, it is difficult to quickly meet increases in demand via planting new trees.[9]

The pursuit of rubber production by imperialists has resulted in numerous abuses and atrocities against the people in the regions where it is grown. Among some examples are the operation set up by King Leopold II of Belgium in Congo is known for its regime of terrorizing, torturing, mutilating, and killing people who refused or could not meet the rubber production quota demanded by the colonial regime.[11] Another example is the Putumayo genocide, which occurred in the Amazon region in the area of the Putumayo River, which was largely carried out by rubber operations such as the Peruvian Amazon Company which would conduct slave raids, torture, and massacres as they forced local indigenous peoples to harvest latex.[12][13]

Production[edit | edit source]

Overview[edit | edit source]

The majority of commercial latex is obtained from Hevea brasilensis trees cultivated in humid lowland tropical conditions.[14] Typically, young Hevea brasilensis trees are raised in a nursery for their first year. The young trees will then be planted in rows on cleared land and take years until they can be tapped.[2] Ground cover is often achieved with legumes,[14] such as soybeans, which also furnish fixed nitrogen.[2] According to the Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry, the economic life cycle of a rubber plantation is 30-35 years, after which replanting is necessary.[14]

In trees ready for tapping, latex is harvested by scoring or cutting the bark of the trees. Latex then flows into a collection cup attached below the cut.[15] Tapping is usually performed in the early morning hours or at night. The flow of latex can be affected by temperature and weather, with latex flowing more easily in cool weather and rainfall curtailing latex flow.[2] The latex from several trees is collected and combined in larger containers. Latex that falls to the ground is also periodically collected.[2]

The collected latex may be coagulated and processed into rubber sheets within the farm or plantation where it was collected, or be collected and sold at a collection station, either in the form of liquid latex or coagulated cup lumps. A farm's scale, complexity, and ownership structure, as well as employment type, working conditions, payment schemes, price fluctuations, and availability and scale of processing facilities are among some of the factors influencing this stage of the process.[16][17][18]

For liquid latex, a common processing method is coagulation, which starts to occur on its own in the collection cups if no preventative chemical such as ammonia is added. This can be harvested and sold in a form known as cup lump.[18] Coagulation is also achieved by adding an acid such as formic acid when the latex from several trees has has been collected and combined.[2][15] The coagulation process takes about 12 hours. This is followed by squeezing water out of the rubber, typically using rollers and mangle machines, and a drying process, achieved by a variety of possible methods, which may include air drying or smoking or both, and which generally requires several days.[2][15] The processed rubber will fall into different grades depending on how it was processed and qualities detected at inspection such as whether it contains dirt or bark, its color, and uniformity.[2]

For packing and shipping, rubber sheets may be piled together and squeezed with a hydraulic press to form a bale. The outer rubber wrap may be coated in a substance such as talc to prevent sticking.[2] The bales are shipped to factories where the rubber is further processed by customizing the rubber's composition with any additives or fillers for its intended use. The additives are mixed in at a below-vulcanizing temperature, then cooled, repeated in stages if necessary. Chemicals for vulcanization are then added. The rubber is then shaped for its intended purpose by a variety of methods. Finally, the rubber is vulcanized to prevent it from getting sticky when hot or brittle when cold.[15]

Approximately 60 to 70% of natural rubber produced globally is used in the manufacture of vehicle tires.[6] Some major tire manufacturers include Bridgestone (Japan), Michelin (France), Goodyear (USA), Continental (Germany), Sumitomo (Japan), Pirelli (Italy), Hankook Tire (south Korea), Yokohama Rubber Company (Japan), and ZC Rubber (China).[19][20]

History[edit | edit source]

Early history[edit | edit source]

Various plants around the world produce latex, and therefore it has long been in use for various purposes in locations where it natively grows. In the Americas, indigenous peoples of the Amazon as well as in Mesoamerica harvested from their local latex-producing plants and processed it in a variety of ways, creating objects such as rubber balls, shoes, containers, syringes, waterproofed clothing, adhesives, hafting bands, as well as using it for medicinal purposes.[1][21]

In ancient Mesoamerica, people mixed latex from the Castilla elastica tree with juice from the Ipomoea alba vine to achieve desired coagulation rates and elasticity properties for different applications.[21] Materials associated with rubber balls excavated in Mexico have been radiocarbon dated as early as 1600 BC, marking the earliest known rubber usage in the world.[21]

In Southeast Asia, a latex-derived material, the plants and material both known in English as gutta-percha, was used by indigenous peoples to create a variety of tools. Gutta-percha is chemically similar to rubber (as a stereoisomer of rubber) but exhibits some different characteristics, making it useful in somewhat different applications.[22]

European colonialism and industrial revolution[edit | edit source]

Europeans gradually became aware of rubber and some of its uses as they observed indigenous harvesting and processing methods in the Americas, with the earliest European accounts of rubber dating from the period of Spanish colonization of the Americas.[1] Europeans likely became aware of rubber producing plants in Africa in the 1760s.[12]:109

European awareness of gutta-percha dates to 1656 when samples of it were brought to London from Southeast Asia. Author John Tully notes that gutta-percha "long remained a curiosity" for Europeans, who regarded it as similar to rubber but inert, hard, and inelastic. It was not until 1832 when a Malay laborer demonstrated to a Scottish physician how to process gutta-percha to make it malleable that it attracted more interest for use by Europeans. Gutta-percha became key in the expansion of the telegraph system, as gutta-percha coating of submarine cables did not degrade in seawater.[22] The rise of European demand for gutta-percha combined with a harvesting method that was not sustainable for that level of demand resulted in massive deforestation where it naturally grew.[22]

As the industrial revolution progressed, European manufacturers created some products out of rubber, although rubber processing techniques at the time somewhat limited its applications as rubber was sticky in temperate conditions, would melt in heat and become brittle in cold, and also retained an unpleasant scent. However, in 1839, the vulcanization process was developed which made rubber able to withstand greater extremes of heat and cold without melting or cracking, as well as removed the undesirable odor.[1] Following this, applications for rubber expanded and the rubber industry grew,[1] leading into a period sometimes called the rubber boom[23] which was further boosted by the development of the pneumatic tire, the popularization of bicycles, and the invention of the automobile.[2]

Rubber boom (c. 1850 - 1919)[edit | edit source]

At the start of the rubber boom in the mid-to-late 1800s,[25] the majority of the world's commercial rubber and gutta-percha was gathered as "wild rubber" from mature plants already growing in the forest, rather than from plantations, although some small-scale rubber plantations did exist.[12] Rubber plantations were not typically pursued in this era as many rubber operation owners took a "get rich quick" approach, opting to enslave people and force them to harvest from mature wild trees rather than bother with the costs of starting a plantation, where immature trees that would not yield latex for years would need to be cared for.[12] Additionally, in the case of rubber operations within the native range of Hevea brasilensis, the tree could not be grown plantation-style as it would be susceptible to local leaf blight when closely planted as a single crop, though it was able to grow among other plants in the wild. However, when planted outside of its native range, Hevea brasilsensis trees could be grown plantation-style without falling to leaf blight, a major factor in the establishment of Hevea brasilensis plantations outside of the Americas.[26]

In the Amazon basin, rubber operations were rife with slavery, and the industry contributed to acts of genocide against indigenous peoples of the region. Latex tappers, the workers who harvest latex, were mainly engaged in a sub-contracting system in which they would typically be trapped into slavery via debt bondage, often starting their work already in debt to their bosses (or enslavers) for the transportation costs to arrive at the work area. Workers in this situation would also have to pay 300-400% higher prices for various goods, the cost of which would be deducted from their pay. These conditions amounted to a truck system or company store model designed to keep the worker in perpetual debt. Regardless of official labor laws at the time in the various countries with rubber operations, the owners of rubber operations would enforce their own arbitrary laws on their enslaved workforce who attempted to escape.[12]

Indigenous peoples of the region were subjected to slave raids and forcibly conscripted into rubber harvesting, facing massacres, torture, and genocide. This was especially the case in operations engaged in harvesting Castilla, as the typical harvesting method was to completely cut down the trees of an area and then move on to the next area found to have the trees. Therefore, instead of long term debt slaves harvesting repeatedly from the same trees in one area, Castilla operations tended toward moving around to different areas and enslaving the local people where they went.[13] Herbert Spencer Dickey, a former staff doctor with the Peruvian Amazon Company, later wrote of his time there, "I grew more and more certain that the Putumayo District was one vast torture chamber, where a handful of rubber officials, whose word was law, tortured and killed and maimed as they, in their degeneracy, saw fit."[12]:94 Roger Casement reported "the destruction of crops over whole districts or inflicted as a form of the death penalty on individuals who failed to bring in their quota of rubber" and "deliberate murder by bullet, fire, beheading, or flogging to death" which was "accompanied by a variety of atrocious tortures".[12]:97

The Congo basin in central Africa is another region which has native latex-producing plants and became another center of violent extraction of wild rubber. King Leopold II of Belgium established what he called the "Congo Free State", a territory approximately eighty times the size of Belgium, following the 1885 Berlin Conference. The Congo Free State's economy was concerned with the extraction of ivory and rubber, with rubber becoming the main focus with the onset of the rubber boom. The main beneficiary of the profits of the Congo Free State was Leopold himself, although large tracts of land were also leased to eight private companies.[12]:109 Numerous atrocities occurred under the regime established by Leopold, including the practice of chopping off hands or otherwise mutilating people who did not meet the rubber quota demanded of them. It is estimated that from 1885 to 1908, the period of Leopold's rule, the population declined from twenty million to ten million.[11]

During the rubber boom, Brazil had a monopoly on the supply of rubber, with the city of Manaus becoming the wealthiest city in South America by the late 1800s.[27] In one of various attempts by the British to gain a foothold in the rubber trade, in 1876 the Home Office commissioned Henry Wickham to smuggle Hevea brasilensis seeds out of the Amazon region. Wickham smuggled out 70,000 Hevea brasilensis seeds and brought them to the UK's Royal Gardens at Kew. At the gardens, the seeds were germinated and then the resulting plants were shipped to British collectors and colonies in Asia. This would eventually lead to the establishment of British colonial rubber plantations in Southeast Asia and the collapse of the wild rubber market in the Amazon, with colonial British plantations supplying the majority of the world's rubber demand by 1919.[28][27][29]

Shift to plantations[edit | edit source]

Following the British smuggling of Hevea brasilensis seeds out of the Amazon region in 1876, the Amazonian wild rubber boom collapsed and world rubber production shifted to other regions, grown mainly in plantations, which was possible to do outside of South America due to the absence of the strain of leaf blight which affected closely planted trees in the Amazon region. By 1913, the output of plantations in Asia exceeded the output of the Amazon region by 25%.[30]:191

British Malaya[edit | edit source]

In the 1890s, it is estimated there were only about 500 acres of rubber plantations in colonial British Malaya, while by 1920 the amount reached nearly 1 million acres.[27] The British sent Indian convicts to work on the plantations without pay as well as recruited Tamil laborers via middlemen. Laborers on the plantations suffered mass malnutrition and death by disease.[27]

French Indochina[edit | edit source]

The French colonial government in what was known as French Indochina made land available to European companies to start plantations there,[31][32] with the first large hevea plantations being started in 1905 and beginning production by 1914.[30]:190 Workers faced widespread injuries, abuses, and cases of malaria and high death rates. When clearing forest to establish new plantations, workers could be crushed by trees, and broken limbs were commonplace. Cases of violent abuse from overseers and cases of self-mutilation and suicide were also prominent.[31][32] Companies began trying to source labor from further away from the plantation regions themselves, so that workers would be further away from their families and communities and therefore less likely to flee.[31][32]

As one article about colonial era plantations in Vietnam observes, "Considering the living and working conditions, it should be of no surprise that colonial plantations became places of radicalization and rebellion. Communist activists saw great potential among the workforce and actively infiltrated ranks to gain supporters, form unions and instigate strikes arguing for better wages and treatment."[31] An article in Binh Duong News explains that the labor struggle on a plantation established by the Michelin Rubber Company in Dau Tieng reached its height in 1933, when over two thousand workers armed themselves with knives and sticks and organized a strike that lasted for several days, forcing the plantation owners to make concessions.[33][34] In 2020, VNExpress reported that a recreation of a colonial era Michelin-owned plantation village may be seen in Dau Tieng District of Binh Duong Province, with the plantation being recognized as a historical monument by the province.[34]

Liberia[edit | edit source]

In 1915, US capitalist Harvey S. Firestone, founder of the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, began searching for plantation sites, initially looking into the Philippines, Malaya, and Sumatra. Firestone attained an initial appropriation of a half a million dollars from the US Congress in 1923 to subsidize his search for plantation sites. Firestone became frustrated by policies in the Philippines which blocked foreigners from owning over 2500 acres of agricultural land and with Filipino nationalists blocking a push in parliament to lift that limit. Thus Firestone turned his attention elsewhere, looking to Liberia for plantation sites.[30]:194

In 1925, Firestone signed a 99-year land lease with the Liberian government. At the time, Liberia was in a weak bargaining position; among various pressures was Liberia's indebtedness to Western banks. A loan negotiated with Firestone was used to pay off the principal and accumulated interest on a previous loan from 1912.[35] The nature of this arrangement is summarized by historian Walter Rodney in How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, "The United States supposedly aided the Liberian government with loans, but used the opportunity to take over Liberian customs revenue, to plunder thousands of square miles of Liberian land, and generally to dictate the weak government of Liberia."[36] Rodney also notes that "the non-monetary benefits to the United States capitalist economy were worth far more than the money returns" as this arrangement provided the US cheap and reliable access to strategic raw materials vital to military and industry.[36]

The 99-year lease Firestone signed with the Liberian government included the use of up to one million acres of land, leasing the land for six cents a year per acre. Additionally, any gold, diamonds, or other minerals found on the land were to become Firestone's property. Exports of rubber were to be taxed at a flat rate of 1% of earnings at New York market prices. Furthermore, after Firestone reached a preliminary agreement with the Liberian government, he unilaterally added a clause to a list of amendments that had been made by the US State Department, in which Firestone made the lease and the building of various infrastructure contingent on the Liberian government taking a $5,000,000 loan from the National City Bank of the Finance Corporation of America, a Firestone subsidiary. This also made Liberia subject to financial supervision by the United States and responsible for paying the appointed financial supervision officials, amounting to a fixed charge of $220,000 a year, which constituted 20% of government revenues in 1928.[30]:194-7

Brazil[edit | edit source]

In the 1920s, US capitalist Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company, attempted to establish "Fordlandia" in Brazil, a plantation which he intended to become a cheap supply of rubber for his company, while also forcing the workers to abide by a specific diet and lifestyle.[37]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 John Tully (2011). The Devil's Milk: A Social History of Rubber: 'Part One'. Monthly Review Press. ISBN 9781583672310

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 Stephen T. Semegen (2003). Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology: 'Rubber, Natural.'. doi: 10.1016/B0-12-227410-5/00670-0 [HUB]

- ↑ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. "Production quantities of Natural rubber in primary forms by country, Average 2020 - 2023" FAOSTAT. Retrieved 2025-11-16.

- ↑ “The ANRPC welcomes governments of natural rubber-producing countries as members. Presently, it consists of 13 countries including Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Vietnam, which collectively represented around 84% of global natural rubber production in 2022.”

"Association of Natural Rubber Producing Countries". Association of Natural Rubber Producing Countries. Retrieved 2025-11-16. - ↑ “In 2023, the countries with the highest share of Rubber in their export portfolios were Cote d'Ivoire (10.7%), Liberia (8.27%), and Laos (2.84%).”

"Rubber Exports divided by a Country's Total Exports (2023)" (2023). The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Archived from the original on 2025-12-05. Retrieved 2025-12-05. - ↑ 6.0 6.1 “Natural rubber (NR) is a critical raw material of great strategic importance in sectors as diverse as healthcare, defense, space, buildings and construction, transportation and vehicle tyres, the latter of which consumes between 60 and 70 percent of global production.”

H.G. Toh. "Message from Secretary - General" Association of Natural Rubber Producing Countries. Retrieved 2025-11-16. - ↑ “But synthetic rubber isn't a cure-all. Natural rubber's unique properties such as heat resistance and durability cannot be reproduced for certain applications, including some military uses. Aircraft tires, for example, require the material's temperature threshold and toughness to withstand wear and tear during takeoff and landing.”

"Why Natural Rubber is a Matter of National Security and Economic Stability" (2025-03-26). MITRE. - ↑ “The sources of various kinds of strategic raw materials necessary for war purposes— coal, oil, non-ferrous and rare metals, rubber, cotton, etc. —are the objects of ferocious conflict.”

Lev Gatovsky, I. I. Kuzminov, Ivan Laptev, Lev Leontyev, Konstantin Ostrovityanov, Anatoly Pashkov, V. I. Pereslegin, Dmitri Shepilov, Vladimir Starovsky, Pavel Yudin (1954). Political Economy. Moscow: Economics Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Is Natural Rubber the Next Critical Material to Challenge the U.S. Economy?" Homeland Security Systems Engineering and Development Institute, 2024-06-24.

- ↑ "Is Natural Rubber the Next Critical Material to Challenge the U.S. Economy?" Homeland Security Systems Engineering and Development Institute, 2024-06-24. Quote: "The Chinese will continue to ensure their access to natural rubber, but they also realize that natural rubber is an Achilles Heel for the United States. Unless we take steps to adequately protect our market access, the U.S. risks a potential economic crisis, and we will not have the same tools that we had during World II to manage such a crisis. That result could potentially be catastrophic and so action may be warranted because the price for inaction may be severe."

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 “[T]he Free State’s officials brutalized the people of the Congo, killing them mercilessly, and torturing those who could not or would not work. Leopold II’s Free State set up the Force Publique, a militia designed to strike terror in the heart of the workforce. If a worker did not work hard, the officer would cut off their hand; one district official received 1,308 hands in one day from his subordinates. Fievez, an official of the Free State, noted of those who refused to collect rubber or else who did not meet their rubber quota, “I made war against them. One example was enough: a hundred heads cut off, and there have been plenty of supplies ever since. My goal is ultimately humanitarian. I killed a hundred people, but that allowed five hundred others to live.” Rape was routine, but so was the mutilation of the male and female genitalia in the presence of family members. To supply the emergent tire industry, Leopold II’s Free State, therefore, sucked the life out of the rubber vines and murdered half the Congo’s population in the process (between 1885 and 1908, the population declined from twenty million to ten million).”

Vijay Prashad (2007). The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World. Libgen. - ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 John Tully (2011). The Devil's Milk: A Social History of Rubber: 'Part Two'. Monthly Review Press. ISBN 9781583672310

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 “The extractive nature of the system also influenced their need for labour. Instead of a docile peon who could be manipulated over years of drudgery, they relied on experienced woodsmen who could identify the Castilla groves and enslaved peons to fell trees and collect the latex. They would migrate with the former and conscript the latter from local Indigenous communities, typically by force, as they needed them. Historians have termed this terrorist slavery, because the caucheros were extraordinarily cruel and treated their peons as an expendable commodity that could be replaced as they expanded into new territories.”

Timothy J. Killeen (2024-11-08). "The rubber boom and its legacy in Brazil, Peru, Bolivia and Colombia" Mongabay. - ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Orwa C, Mutua A, Kindt R, Jamnadass R, Simons A. (2009). "Hevea brasiliensis" Agroforestree Database, World Agroforestry. Archived from the original on 2025-04-25. Retrieved 2025-12-05.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Karen G Blaettler (2022-03-24). "The Manufacturing Process Of Rubber" Sciencing. Archived from the original on 2025-12-05.

- ↑ “Working conditions in Sukamade plantations vary but are often challenging. [...] Wages for latex workers in Sukamade are relatively modest, reflecting the economic challenges of many rural regions in Indonesia. A latex tapper earns an average of 100,000 to 150,000 IDR (about $7 to $10) per day. This wage can vary based on experience, productivity, and specific agreements within each plantation.”

Damien Lafon (2024-08-19). "The Production Of Latex And Rubber In Indonesia" Terra Cultura. Archived from the original on 2025-06-19. - ↑ “Around 7,000 employees and their families live on what the company describes as the world’s largest contiguous natural rubber farm, relying on Firestone for food, education, and medical care. [...] These days, most of the world’s natural rubber comes from small, family-owned farms in Asia, which sell to a network of distributors. Firestone’s sprawling rubber plantation in Liberia, established a century ago, is a relic of a bygone era of the industry. [...] Contract workers, who are primarily employed as “tappers,” told researchers that they must work 50-60 hours per week to reach production quotas, or risk being fired. According to the report, workers are not paid for overtime, in defiance of Liberian law, which requires overtime pay after 48 hours of work. And because some workers are paid per pound of dried latex extracted, pay can fall below Liberia’s minimum wage of $5.50 a day.”

Serena Lin (2025-01-30). "The World’s Largest Rubber Plantation is About to Go on Strike" Mother Jones. Archived from the original on 2025-07-11. - ↑ 18.0 18.1 “According to Kameruzaman, there are about 450,000 Malaysian families involved in the rubber sector. This adds up to 2.25 million people, or an average of five people per family, who live off the commodity. [...] Abdullahrus taps his trees only on weekends and collects the cup lumps in the early part of the following week. [...] Sivakumaran, who has served with LGM and the Rubber Research Institute of Malaysia, adds that smallholders have to travel some distance to deliver the latex to factories whereas, in the case of cup lumps, collectors operate in virtually all the towns in Malaysia.”

Jenny Ng and Muhammed Ahmad Hamdan (2020-09-10). "Cover Story: The plight of Malaysia’s rubber smallholders" The Edge Malaysia. Archived from the original on 2025-12-06. - ↑ "The Largest Tire Manufacturers in the World (New)" (2023-06-26). Car Logos.

- ↑ Gabriel Patrick (2025-10). "10 largest tire manufacturers cruising through the roads" Verified Market Research.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Michael J. Tarkanian and Dorothy Hosler (2011). America's First Polymer Scientists: Rubber Processing, Use, and Transport in Mesoamerica, vol. 22, No. 4. Latin American Antiquity.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 John Tully (2009). "A Victorian Ecological Disaster: Imperialism, the Telegraph, and Gutta-Percha." Journal of World History, 20(4), 559–579. doi:10.1353/jwh.0.0088

- ↑ Bradford L. Barham and Oliver T. Coomes (1994). Reinterpreting the Amazon Rubber Boom: Investment, the State, and Dutch Disease. Latin American Research Review. doi: 10.1017/S0023879100024134 [HUB]

- ↑ “The series Castigos del caucho by Santiago Yahuarcani originates in the oral memory transmitted by the artist’s grandfather, who was a survivor of the Putumayo genocide where thousands of Indigenous people were annihilated and enslaved to extract rubber from the Amazon forest between 1879 and 1912.”

"Santiago Yahuarcani Castigos del caucho 2017". KADIST. Archived from the original on 2025-12-25. - ↑ “American historian Lewis Tambs dates the start of the Amazonian rubber boom from 1820. More prudently, Barbara Weinstein dates the start of the boom to 1850, with the demand for raw rubber accelerating following the discovery of vulcanization in 1839. Another writer believes that until 1889 “the rubber trade was characterized by a steady and reasonable growth.” After that, with the mass production of pneumatic tires for bicycles and cars, the demand for rubber became insatiable in “a succession of waves which took prices to new levels.” Finally, in 1910 came the dizzying final surge, which took the price of raw rubber to around three dollars a pound, followed by a sudden and catastrophic crash. By 1919, the price had fallen to about fifty cents a pound and the boom was over for good.”

John Tully (2011). The Devil's Milk: A Social History of Rubber (pp. 68-9). Monthly Review Press. - ↑ “While Hevea brasiliensis grows happily interspersed with other trees in the Amazon forests, attempts to cultivate it on plantations fell victim to leaf blight, a fate that all the wealth of the U.S. tycoon Henry Ford could not change.”

John Tully (2011). The Devil's Milk: A Social History of Rubber (p. 72). Monthly Review Press. - ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Nick Baker and Marc Fennell (2024-08-05). "The rubber seed 'heist' that changed the course of history" Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 2025-12-21.

- ↑ Peter Parker (2008-09-27). "Review: The Thief at the End of the World by Joe Jackson" The Telegraph.

- ↑ "PIONEER IN RUBBER, IS DEAD IN LONDON; Sir Henry Wickham Made It Possible for World to Rideon Auto Tires." (1928-09-28). The New York Times.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 John Tully (2011). The Devil's Milk: A Social History of Rubber: 'Part Four: Plantation Hevea: Agribusiness and Imperialism'.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Paul Christiansen (2025-03-07). "The Harrowing History of Vietnam's Rubber Plantations" Saigoneer. Archived from the original on 2025-04-25.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Eric Panthou (2014). "The late provision of medical care to coolies in Indochinese rubber tree plantations: the Michelin model health unit set up in 1925–1939." HAL. Archived from the original on 2025-02-07.

- ↑ Hong Thuan (2020-03-06). "A historic rubber plantation" Binh Duong News. Archived from the original on 2024-06-02.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Phuoc Tuan (2020-01-29). "Rubber plantation village commemorates French colonial oppression" VNExpress. Archived from the original on 2025-10-17.

- ↑ “It was only after a new loan was negotiated with the Firestone Corporation of America in 1926 that the Liberian Government was able to use $1,180,669 to pay off the principal and accumulated interest on the 1912 loan. The loan offered by Firestone was in the region of $5 million, at an interest rate of seven per cent, but by 1945 still only half of this amount had been subscribed. Firestone stipulations included the abolition of the office of Receiver of Customs and its replacement by a Financial Adviser. It was under pressure of these debts that Liberia was obliged to cede large concessions for rubber planting to Firestone, and later to the Goodrich Rubber Company.”

Kwame Nkrumah (1965). Neocolonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism: 'The Truth Behind the Headlines'. - ↑ 36.0 36.1 Walter Rodney (1972). How Europe Underdeveloped Africa: 'Colonialism as a Prop to Metropolitan Economies and Capitalism as a System'.

- ↑ "Fordlandia: The Failure Of Ford's Jungle Utopia" (2009-06-06). NPR. Archived from the original on 2025-09-29.