More languages

More actions

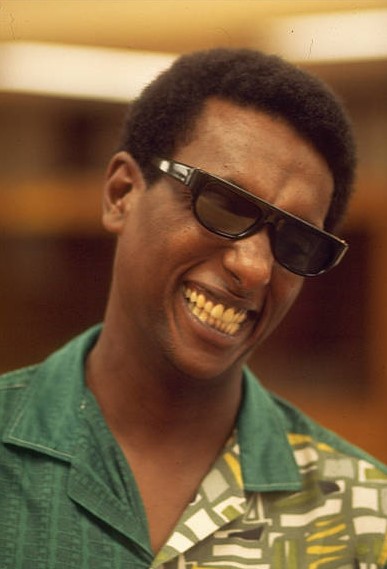

Kwame Ture | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Kwame Ture | |

| Born | Stokely Standiford Churchill Carmichael June 29, 1941 Port of Spain, British Trinidad and Tobago |

| Died | November 15, 1998 (Age 57) Conakry, Guinea |

| Cause of death | Prostate Cancer |

| Nationality | Guinean |

| Political orientation | Communism Nkrumahism (developed what is now known as Nkrumahism-Toureism-Cabralism) Scientific Socialism Pan-Africanism |

| Political party | Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Black Panther Party Democratic Party of Guinea - African Democratic Rally All-African People's Revolutionary Party |

Kwame Ture, born Stokely Carmichael, was a prominent civil rights organizer and founder of the Black Power movement. After studying Marxist theory in high school, Ture would go on to embrace political activism throughout his years in Howard University. During those years, he was introduced to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which despite being founded on the belief that racism and apartheid could be ended through nonviolence, the influences and later the leaderships of Kwame Ture and H. Rap Brown would lead the organization into becoming a hotbed for Black Power ideology. While leading SNCC, Kwame Ture led an ideological shift which resulted in the expulsion of white members from the organization, denunciation of Zionism and capitalism and calls for Black Power as a means to counteract white supremacy. After taking up Nkrumah's offer while in Conakry, Kwame Ture moved to Guinea, where he befriended Co-Presidents Sekou Touré and Kwame Nkrumah and lived with his wife, Mariam Makeba. The purpose of him moving was to build the All-African People's Revolutionary Party and carry out a continental war of people's liberation.[1]

Biography[edit | edit source]

Early life[edit | edit source]

On June 29th, 1941; Stokely Carmichael was born in his father's house in the city of Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago. His father, Adolphus Carmichael, was a carpenter[2] and had built the house in which he and his family resided in.[3] In 1944 his mother, Mabel Carmichael, who was born in the US Panama Canal Zone,[4] moved to the United States due to tensions with her in-laws.[5] Two years later his father would join her in Harlem,[6] leaving Stokely to be raised by his grandmother and aunts for 6 years.[7]

At 11 years old, Stokely and his siblings then moved to his parents to New York; where the Carmichaels lived as one of the few Africans in a predominantly white community in the Bronx populated by Italian, Irish and Jewish folk.[8] His father was able to purchase the home in the white community due to it being cramped and ugly, making it undesirable for most buyers.[9][10] Because of the building's state, Adolphus Carmichael worked tirelessly to renovate and improve the house,[11] thus gaining respect from the locals.[12] After being integrated with the locals, Stokely engaged in petty theft due to peer pressure from his friends[13], but later left the Morris Park Dukes street gang after they started producing zip guns.[14]

Bronx Science[edit | edit source]

Carmichael was later enrolled at the Bronx High School of Science, an elite predominantly white school in his area.[15][16] While in high school, Stokely consistently excelled beyond his peers despite their affluent backgrounds and became an exotic attraction to white observers as a result.[17] During these years, Stokely befriended Gene Dennis, a member of the Young Communist League (YCL) and son of Communist Party USA member Eugene Dennis.[18] This friendship introduced the young Carmichael to a series of YCL meetings and study sessions.[19] His introduction to Marxism also heightened his interest in politics,[20] which over time made him familiar to names like Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky.[21] Despite this, he didn't join any Marxist organizations[22] nor adopted Marxism due to his religiosity and felt doing so would alienate him from the black community.[23] When attending a political meeting with students from Science, Stokely was introduced to Bayard Rustin;[24] who's performance commanded his attention as it was a rare moment of a meaningful black presence in communist circles.[25] Although he did meet black members of communist leadership at Gene's house, Stokely considered them distant unlike Rustin.[26] Carmichael's impression of Rustin led him to turn to authors C. L. R. James and George Padmore.[27] As he read both enthusiastically, Stokely noticed the contrast on their reception among white Marxists and black nationalists on 125th Street.[28] On the rare occasions when Padmore and James were brought up, white leftists and members of the Young Communists were dismissive of both; dismissing Padmore as if he had abandoned communism[29] and outing James as a Trotskyite.[30] The nationalists on 125th street however praised both as African revolutionaries and promoted their works.[31][32] Carmichael also contrasted the rhetoric the Young Communists espoused in support of labor unions with discussions with his father and his friends about their treatment by labor unions and white workers at their jobs.[33]

His junior and senior years saw his political life grew more active when presented with the popularity and successes of Dr. King's nonviolent movement in Alabama.[34] Due to King managing to rake in support among white moderates to combat Jim Crow, Stokely respected King and became an avid supporter.[35] The 125th street nationalists however were critical of King's nonviolence and mocked his movement,[36] prompting him to disassociate with them.[37] He and a group of Science student activists often attended peace rallies called by the Ban the Bomb movement while supporting Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) demonstrations against segregation.[38] Stokely also protested the Sharpeville massacre and helped Bayard Rustin organize one of his "Youth Marches for Integrated Schools," where he might have first heard King address a large crowd of people.[39] While protesting against the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) with local communists, Carmichael continued noted the lack of Africans present, which he found typical of the leftist political functions at Science.[40] It was at the protest where he discovered mostly black group associated with the D.C's Nonviolent Action Group (NAG).[41] NAG was primarily made up of Howard University students, though it was never a recognized campus organization.[42] After joining NAG's picket at the White House,[43] Stokely decided to apply to Howard University so that he could participate in NAG.[44]

Howard University[edit | edit source]

Once graduating in 1960, Carmichael enrolled at Howard University where he would receive his degree in Philosophy. Initially, Stokely struggled to find NAG due to their lack of recognition as a student organization; however after two days of searching he came across one of the anti-HAUC protestors who informed him of NAG's meeting dates and location. After two weeks as a university student, he was initiated into NAG. Because Howard's funding was controlled by Democrat controlled congressional committees, Stokely and his peers believed the school administration was refusing to recognize NAG in an effort to secure its funding. Unlike other universities which relied on state funding, Howard administrators refused to acknowledge NAG's existence; meaning they didn't need to apply pressure to student activists on campus. At Southern University in Baton Rouge the opposite transpired, resulting in the expulsion of all student activists on campus. Around 50 students were expelled, among which were Eddie C. Brown and his young brother H. Rap Brown, who also ended up in NAG. As a young adult in Howard, Stokely was introduced to the immense self-immolation of black identity that was omnipresent in campus, as well as the attempts to prevent African immigrants from interacting with Afro-Americans. The latter was brought to his attention during the school's orientation for foreigners, in which administrators warned them not to interact with "American Negros" on the basis of cultural differences and community violence. In another instance, his girlfriend was threatened with expulsion for wearing her natural hair.[1]

SNCC[edit | edit source]

In the aftermath of the Greensboro sit-ins, a nation-wide trend of social activism began to take place. Initially, Stokely didn't think much of it given it was a minor case of African-Americans sitting at a segregated area. Soon afterwards, however, sit-ins began to take place across the Black Belt before spreading across the rest of the United States four months later. The rise in public disobedience and participation in the civil rights movement then led to Ella Baker founding the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) two months later with the help of Dr. King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Despite King's intention of creating a youth wing subordinate to the SCLC, Ms. Baker envisioned an independent student movement and refused to be apart of any arrangement that would lead to the coopting of the student movement by Dr. King and his ministers of the SCLC, prompting her to walk out of the student conference that created SNCC.[1]

Library works[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Ready For Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture)

- ↑ “Among his varied talents, the late Adolphus Carmichael was by profession a master carpenter”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready For Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Oriki: Ancestors and Roots' (pp. 12-13). [PDF] - ↑ “I was born in the house my father built for his family at 54 Oxford Street at the bottom of the forty-two steps in the city of Port of Spain, Trinidad”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready For Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Oriki: Ancestors and Roots' (p. 12). [PDF] - ↑ “My mother's father, Mr. Joshua Charles, was born in Antigua. A colonial policeman, he had been posted to Montserrat, where he met my grandmother. He was then posted to Nevis, where, like thousands of Caribbean black men, he was forced by economic conditions to work in the building of the Panama Canal. Unlike most though, Grandfather Charles brought along his young bride, which is how my mother and all her siblings came to be born in the Canal Zone.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready For Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Oriki: Ancestors and Roots' (p. 15). [PDF] - ↑ “So in October of 1944, leaving husband, young children, and the ultimatum "You will have to choose," behind her, Mabel Florence Charles Carmichael, aged twenty-three and looking much younger, set out for God's Country. Not in search of a "better" life or the American Dream, but in impulsive flight and as a personal declaration of independence from domineering in-laws.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for the Revolution: 'Oriki: Ancestors and Roots' (pp. 20-21). [PDF] - ↑ “So in June of 1946, the otherwise utterly law-abiding Adolphus Carmichael signed on as an able seaman on a northbound freighter, jumped ship in New York harbor, and reunited with his wife. My sister was four, I almost five, and Lynette an infant. We were not to see either parent again until I was almost eleven.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready For Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Oriki: Ancestors and Roots' (p. 21). - ↑ “This, then, was the family of my childhood, my grandma, her three adult daughters, and the four children. [...] All the aunts worked while Grandma was responsible for the children during the day. Tante Elaine, Austin's mom, was a teacher at Mr. Young's private school. She brought to the household a rigorous attention to order, detail, and duty. She also brought home her reverence for education and the strict administration of discipline, which were projections of the classroom persona of all colonial schoolteachers of the time. Mummy Olga, more fun-loving and easygoing, worked in a department store, where dealing with the public was an occupation well suited to her outgoing, friendly nature.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready For Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'The House at the Forty-Two Steps' (p. 23). [PDF] - ↑ “The house was farther up in the Bronx, on Amethyst Street, in the Morris Park/White Plains Road area, not far from the Bronx Zoo. We would discover that the neighborhood was heavily Italian with a strong admixture of Irish. It was respectable working class, "ethnic, and very, very Catholic. On one side it bordered Pelham Parkway, across which was a predominantly Jewish enclave. Ours would be the first, and for much of my youth, the only African family in that immediate neighborhood.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'A Better Neighborhood' (p. 60). [PDF] - ↑ “It was a dump. I mean, it was a serious, serious dump. In fact, it was the local eyesore, and the reason-I now understand clearly-my father had been able to get the house with no visible opposition was because it was, hands down, the worst house on the block. It was so run-down, beat-up, and ill kept that no one wanted it. If that house were a horse, it would have been described as "hard rode and put up wet." A creature in dire need of a little care and nurturing. My dad was the "sucker" the owners had "seen coming" on whom to unload their white elephant. Which is one reason, I'm sure, the race question was overlooked. Who else could have been expected to buy such a wreck?”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready For Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'A Better Neighborhood' (p. 61). [PDF] - ↑ “When we first saw it, we children were shocked. We looked around the house and at each other. I mean, even the cramped quarters at Stebbins looked like a mansion compared to what we were moving into. I mean, small, little, squinched-up rooms, dark, sunless interiors, filthy baseboards, a total mess and not at all inviting.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'A Better Neighborhood' (p. 61). [PDF] - ↑ “Immediately when we moved in-my mother used to tease him fondly that he unpacked his tools before he unpacked his bed-my father set to work, even though it was January and cold. The remake took a long time, continuing in some way as long as he lived there. On those happy days when he had a construction job, my father worked on our house at night. On those all too many days when the union hiring hall failed to refer him to a job, he worked on our home day and night. Before he was through he had added rooms upstairs and down, knocked out walls to create more space, put in windows and doors. In a word, he completely transformed that wreck.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'A Better Neighborhood' (p. 61). [PDF] - ↑ “We learned later that as the neighbors looked on, amusement turned to skepticism, skepticism to wonder, and wonder to respect. They were, after all, working men and respected industry and competence.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'A Better Neighborhood' (p. 61). [PDF] - ↑ “Until that one night when I was hanging out and Paulie proposed that we rip off a store. And as he did so, he seemed to be looking straight at me. It was a test of some sort, that was clear. I had to calculate rather quickly. I understood clearly the stupidity of this act, but there was the pressure to belong. It was very much "All right, are you down with us or not?" Very much as if, you punk out now and you won't be able to hang no more. We'll know who you are. That kind of pressure.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'A Better Neighborhood' (p. 66). [PDF] - ↑ “When the zips were made, some actually fired, most didn't. I can't now remember whether mine did. But this was the final act in my flirtation with the destructive behavior of our wanna-be gang. Now that we had guns that fired-at least a few did-were we really going to shoot, possibly maim or even kill, some kid we didn't even know? I am sure the Dukes never did, but I sure wasn't about to tag along to find out.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'A Better Neighborhood' (p. 70). [PDF] - ↑ “Within our family, the news of my selection to Science had been greeted with quiet satisfaction, entirely as if it were no less than had been expected of me. My parents knew that Science was an "elite" school, carefully selecting and preparing the city's brightest students for college. This fit neatly with a plan being developed by my father, who in his heart had never really left his beloved Trinidad.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (p. 84). [PDF] - ↑ “Some were very affluent, the children of wealthy Park Avenue professionals and corporate executives. But the majority were just middle class kids of college-educated parents, WASP, Jewish, Irish, Italian, and a few Africans born in America. Of some two thousand students at Science, about fifty or sixty were Africans from America. Some students were working class, or like me, first-generation immigrants from Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, or Latin America. That first day, the only kid I knew in the freshman class was Lefty Faronti, who was working-class Italian from my Bronx neighborhood.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (p. 84). [PDF] - ↑ “The mother was effusive. "Oh, Stokely, I've heard so much about you. How smart you are, your sense of humor. How handsome, what features you have, etc." The way she went on was embarrassing, it was clear I was the exotic featured attraction. When I was leaving I said my good-byes and thanked the mother. One of her friends must have said something which I didn't hear. But I distinctly heard the mother's answer before the elevator door closed. It had a certain smugness I didn't like. "Oh, yes, of course," she said. "We allow Jimmy to hang out with Negroes."”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (p. 90). [PDF] - ↑ “"Oh, only what everyone else knows, Carmichael. His father, Eugene Dennis Sr., is a high-level operative in the Communist Party U.S.A. He was jailed under the Smith Act. Your friend Gene is one of the bright hopes of the Young Communist League in America. Anything else you want to know?"”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (p. 91). [PDF] - ↑ “Anyway, over the next four years, the friendship between Gene and me grew closer and my parents' initial concern shriveled away. But in one sense, I guess, my Italian classmate's prediction was accurate. I don't believe I became anyone's "dupe, but it wasn't too long before I was going to meetings of the Young Communist League, attending study groups, and eventually attending their rallies.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (p. 92). [PDF] - ↑ “That was wondrously exciting intellectually. Marxism offered me an approach, a coherent point of view from which to understand and engage society, in terms of the "forces of history." These people impressed on me that to bring about social change you had to study and clearly understand the forces of society. It's probably not really true that my political attitudes were formed here, but my interest in political struggle was heightened and I learned that a strong theoretical base required systematic study and that regular theoretical study is a constant political duty.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (p. 92). [PDF] - ↑ “I became familiar with names like Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Trotsky and other revolutionary thinkers, whom I read for the study groups. Out at camps in the New York or New Jersey woods, we'd discuss particular books, current political developments, struggles that were going on, what our attitudes ought to be, what tactics ought to be employed, and so forth.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (p. 92). [PDF] - ↑ “But I joined neither the Young Communist League nor the youth wing of the Socialist Party, neither the Socialist Party of America nor the Socialist Workers Party.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (p. 93). [PDF] - ↑ “You could say, I suppose, that my reasons for not joining were cultural. The longer I was around my Communist friends, the more complicated my reservations became, but at first it was simple: the religious question. I was, like most Africans, very religious, coming as I did from a very religious family. And you know that one of my early career options was the clergy. However, most of the youth in the Young Communist League were-publicly anyway-devout atheists. They often made jokes about God, and while I appreciated these young comrades and respected them, those anti-God jokes-funny as some of them were-were initially shocking and very, very offensive to me. [...] I did not want to be alienated from my people because of Marxist atheism.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (pp. 93-94). [PDF] - ↑ “At a political meeting, a group of us from Science were there, but I was the only African. Though I cannot remember clearly the debate, what I cannot forget is the intervention of a voice. A clear, ringing voice, a high tenor, precise in diction. [...] I sat up. "Who the hell is that?" I asked Gene. "Why," he said, "that's Bayard Rustin, the socialist." "That's what I'm gonna be when I grow up," I whispered exultantly.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (pp. 94-95). [PDF] - ↑ “I also think that this first impression was as great as I remember it because what I had been missing in these circles without necessarily being aware of it was a powerful and compelling black presence. Of course Rustin's eloquence, debating skill, analytic and strategic deftness, and practiced ease with which he captured the audience had all impressed me. But it was his blackness that had inspired.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (p. 95). [PDF] - ↑ “Of course there were African men in high positions in the hierarchy of the Communist Party, and by then I'd even met some of them at Gene's house, but it wasn't quite the same. They impressed me as stolid, dour, somehow distant, rather shadowy presences. Bayard was dramatic and obviously engaged.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (p. 95). [PDF] - ↑ “Eventually I was further distracted from Communism by two literary influences from my other cultural life. Coincidentally, both were men native to Trinidad: C. L. R. James and George Padmore.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (p. 95). [PDF] - ↑ “At first these two worlds of mine rarely intersected, but when they did, there was a friction that threw off hot sparks. For me one of these points of friction was in deciding which political writers should be read, given attention, and studied. So far as the white leftists were concerned, no African revolutionary thinkers seemed worthy of serious regard.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (p. 104). [PDF] - ↑ “But on the rare occasion when George Padmore's name came up among the Young Communists, the tone was dismissive, as if he were some kind of renegade, almost as if he were a traitor who had abandoned Communism.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (p. 104). [PDF] - ↑ “Whenever C. L. R. James's name came up among the white leftists I knew in high school, he was more or less pigeonholed as a "Trotskyite," hence a revisionist and apostate from the "correct" line.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (p. 105). [PDF] - ↑ “On 125th Street, though, the names George Padmore and occasionally C. L. R. James were mentioned as important African writers who were revolutionary thinkers.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael: 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (p. 104). [PDF] - ↑ “One of the great political and cultural resources for me at this time was Michaux's famous African Bookstore on 125th Street, which I would visit every chance I got. Mr. Michaux saw that I liked to read about our people and took an interest in me. One day I asked Mr. Michaux about Padmore. He showed me a copy of Padmore's Pan-Africanism or Communism and explained that Padmore was a great Pan-Africanist thinker who was an adviser or mentor to Kwame Nkrumah. I was fascinated. I did not have the money at the time to buy the book, but I skimmed through it eagerly. Later I would study Padmore and become one of his greatest supporters.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (p. 104). [PDF] - ↑ “The first simple and concrete example I had was that of trade unions and "working-class solidarity." I could not reconcile the way my young white comrades talked about the labor movement and working-class empowerment with the discussions of my father and his friends about their treatment at the hands of the union and the white workers on their jobs and the Mafia.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Bronx Science: Young Manhood' (p. 104). [PDF] - ↑ “During my junior and senior years, my political life had become more active. And to my great delight most of the action was coming from the African community. Ever since Montgomery, Dr. King and his nonviolent actions had become more of a presence in the political discussion among New York progressives.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for the Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Howard University: Every Black Thing and Its Opposite' (p. 111). [PDF] - ↑ “I and my friends in Kokista respected Dr. King a great deal because he had found a tactic that put thousands of people in motion to confront racism. And in Montgomery-the cradle of the Confederacy-the organized and unified African community had won big.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for the Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Howard University: Every Black Thing and Its Opposite' (p. 111). [PDF] - ↑ “To be sure, the 125th Street nationalists did not support Dr. King. They attacked nonviolence, mocked his talk of redemptive suffering, and questioned the feasibility and desirability of "integration" as a goal. They felt Dr. King was "begging white folks to accept us," something white folks had never done in three hundred years.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for the Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Howard University: Every Black Thing and Its Opposite' (p. 111). [PDF] - ↑ “I parted company with the nationalists on Dr. King. It seemed clear to me then that nonviolent mass action was an effective tactic. I supported any strategy that could move the Southern masses of our people to confront American apartheid. And any leader who could inspire them to this kind of direct action had my complete respect.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for the Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Howard University: Every Black Thing and Its Opposite' (p. 111). [PDF] - ↑ “In 1960, when the Southern student sit-ins began, CORE would picket department chain stores that discriminated in the South. We Science activists always supported those demonstrations. [...] We would also go to peace rallies called by the Ban the Bomb movement.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Howard University: Every Black Thing and Its Opposite' (p. 111). [PDF] - ↑ “In my senior year, the Sharpsville Massacre occurred on March 21, 1960. The South African police and military fired on a nonviolent march of unarmed Africans killing sixty-nine and wounding over three hundred. I joined a large march from Harlem to the United Nations in protest. Earlier, I helped organize students for one of Bayard Rustin's "Youth Marches for Integrated Schools," which were mounted in Washington. I believe that this might be where I first heard Dr. King address a large group, but I can't really remember.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Howard University: Every Black Thing and Its Opposite' (p. 112). [PDF] - ↑ “Early in my senior year the Young Communists at Science organized a bus for a demonstration against the House Un-American Activities Committee in Washington. I was on the bus. I am not sure whether I was the sole African on that bus, but ifl wasn't, we sure were not many. This would not have been unusual in left political actions at Science, so I never gave it a thought.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Howard University: Every Black Thing and Its Opposite' (p. 112). [PDF] - ↑ “As we approached the pickets, I saw something that would profoundly affect the direction of my life. A section of the line was black. The marchers were not only all African, but they were all about my age. Man, I jes' rushed over. "Hey, y'all. Who are you guys with? The Young Socialists? The Communists?" "No, man. We're NAG," said a brother who introduced himself later as John Moody.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Howard University: Every Black Thing and Its Opposite' (p. 112). [PDF] - ↑ “But this was never the position of the administration. Which is why NAG was never a recognized student organization at Howard. Every year we petitioned. Every year the Student Government and the students supported us. Every year the initiative ran into the most skillful, stubborn, and barefaced obstructionism from the Student Activities bureaucracy. Processes were arbitrarily changed, suspended, or ignored; committees dissolved or simply did not meet all year; or else meetings were summarily adjourned before a final vote could be taken.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Howard University: Every Black Thing and Its Opposite' (p. 117). [PDF] - ↑ “I jumped in the line and the brothers and sisters told me about Howard and NAG. That they were affiliated with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). That they had been campaigning in Virginia and Maryland and in D.C., the nation's capital. They struck me as smart, serious, political, sassy-and they were black. All the way back to New York I was intensely excited. I was surprised at how excited I'd become to discover young Africans who were committed activists. But I was pretty certain that I'd solved the college question.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Howard University: Every Black Thing and Its Opposite' (p. 112). [PDF] - ↑ “In my mind, the choice of college had been a done deal from the conversations on that picket line at the White House. When we'd left, I'd said, "I'll see you in September." And while I would apply to and enroll at Howard University, it was NAG I was really joining.”

Kwame Ture (2003). Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture): 'Howard University: Every Black Thing and Its Opposite' (p. 113). [PDF]