More languages

More actions

(Changed 'Untermensch' (singular) to 'Untermenschen' (plural)) Tag: Visual edit |

(Further reading) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

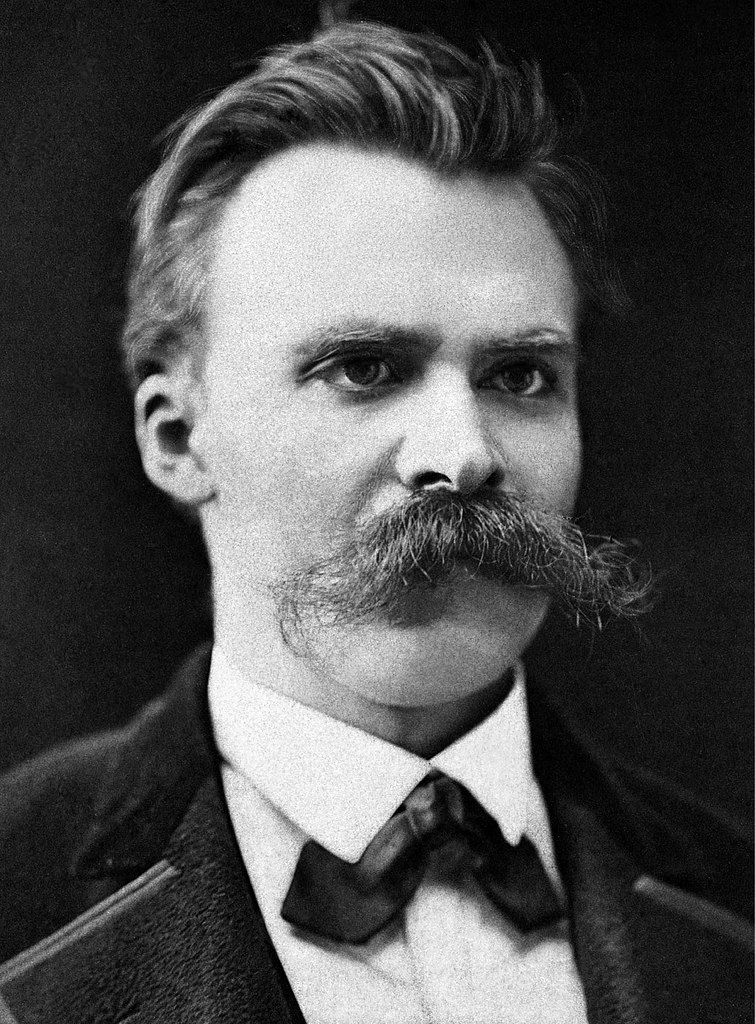

{{Infobox philosopher|name=Friedrich Nietzsche|image=Nietzsche.png|image_size=200|nationality=German|death_place=Weimar, [[German Empire]]|death_date=25 August 1900 (aged 55)|birth_date=15 October 1844|birth_place=Röcken, Saxony, [[Prussia]]|school_tradition=[[Atheism]]<br>[[ | {{Infobox philosopher|name=Friedrich Nietzsche|image=Nietzsche.png|image_size=200|nationality=German|death_place=Weimar, [[German Empire]]|death_date=25 August 1900 (aged 55)|birth_date=15 October 1844|birth_place=Röcken, Saxony, [[Prussia]]|school_tradition=[[Atheism]]<br>[[Irrationalism]]<br>[[Metaphysics]]}} | ||

'''Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche''' (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist and a composer who was notable for exerting a profound influence in contemporary philosophy. His writing spans philosophical polemics, poetry cultural criticism, and fiction that has a fondness of displays aphorisms and irony. | '''Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche''' (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a reactionary German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist and a composer who was notable for exerting a profound influence in contemporary philosophy. His writing spans philosophical polemics, poetry cultural criticism, and fiction that has a fondness of displays aphorisms and irony. | ||

The prominent elements of his philosophy included his radical critique of truth in favor of perspectivism; a genealogical critique of religion and Christian morality and a related theory of the master-slave morality; the aesthetic affirmation of life in response to both the death of God and the profound crisis of nihilism; the notion of Apollonian and Dionysian forces and a characterization of the human subject as the expression of competing wills that are collectively understood as the will of power. In his later novels, he was preoccupied with the creative powers of the individual to overcome cultural and creative mores in pursuit of new values and aesthetic health. | The prominent elements of his philosophy included his radical critique of truth in favor of perspectivism; a genealogical critique of religion and [[Christianity|Christian]] [[morality]] and a related theory of the master-slave morality; the aesthetic affirmation of life in response to both the death of God and the profound crisis of [[nihilism]]; the notion of Apollonian and Dionysian forces and a characterization of the human subject as the expression of competing wills that are collectively understood as the will of power. In his later novels, he was preoccupied with the creative powers of the individual to overcome cultural and creative mores in pursuit of new values and aesthetic health. | ||

His bodies of work touched a wide range of topics that included art, philology, history, music, religion, tragedy, culture and science. He drew inspiration from Greek tragedy as well as figures that included Zoroaster, Arthur Schopenhauer, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Richard Wagner as well as Johan Wolfgang von Goethe. | His bodies of work touched a wide range of topics that included art, philology, history, music, religion, tragedy, culture and science. He drew inspiration from Greek tragedy as well as figures that included Zoroaster, [[Arthur Schopenhauer]], Ralph Waldo Emerson, Richard Wagner as well as Johan Wolfgang von Goethe. | ||

He rejected the existence of a God in favor of a supposed superhuman (''Übermensch'') a concept that was used by the [[National Socialist German Workers' Party]] to murder numerous ''Untermenschen'' (or subhumans) that included [[Judaism|Jews]], [[Republic of Poland|Poles]], [[Slavs]] and other "races" the Nazis considered inferior.<ref>{{Web citation|author=Ishay Landa|newspaper=[[Red Sails]]|title=Aroma and Shadow: Marx vs. Nietzsche on Religion (2005)|date=2023-02-08|url=https://redsails.org/aroma-and-shadow/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230209114749/https://redsails.org/aroma-and-shadow/|archive-date=2023-02-09|retrieved=2023-02-17}}</ref> | == Political views == | ||

Nietzsche said that, "This world is the will to power—and nothing besides." conflated [[appropriation]] (acquiring [[Private property|property]]) and [[exploitation]]. His views were similar to [[Thomas Hobbes]] but more reactionary due to historical context. He called [[socialism]], "the logical conclusion of the tyranny of the least and dumbest" and the survival of the least fit. He believed that the masses, which he called "herd animals," were violently taking power away from the "noble" elements that deserved to rule. He said that humanity would collapse without [[slavery]].<ref>{{Web citation|author=[[John Bellamy Foster]]|newspaper=[[Monthly Review]]|title=The New Irrationalism|date=2023-02-01|url=https://monthlyreview.org/2023/02/01/the-new-irrationalism/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230806060940/https://monthlyreview.org/2023/02/01/the-new-irrationalism/|archive-date=2023-08-06}}</ref> | |||

== Influence == | |||

Nietzsche rejected the existence of a God in favor of a supposed superhuman (''Übermensch'') a concept that was used by the [[National Socialist German Workers' Party]] to murder numerous ''Untermenschen'' (or subhumans) that included [[Judaism|Jews]], [[Republic of Poland|Poles]], [[Slavs]] and other "[[Race|races]]" the Nazis considered inferior.<ref>{{Web citation|author=Ishay Landa|newspaper=[[Red Sails]]|title=Aroma and Shadow: Marx vs. Nietzsche on Religion (2005)|date=2023-02-08|url=https://redsails.org/aroma-and-shadow/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230209114749/https://redsails.org/aroma-and-shadow/|archive-date=2023-02-09|retrieved=2023-02-17}}</ref> | |||

By many accounts, while Nietzsche himself coined the terms Übermensch and Untermensch, he did not mean them literally and only as an allegory. His sister Elizabeth, who survived him by 35 years, was ostensibly the one who rewrote parts of Nietzsche's writings to fit the Nazi ideology. This version of events, however, is still being discussed in [[Marxism|Marxist]] circles, with many pointing to Nietzsche's writings as always containing a kernel of [[proto-fascism]]. | By many accounts, while Nietzsche himself coined the terms Übermensch and Untermensch, he did not mean them literally and only as an allegory. His sister Elizabeth, who survived him by 35 years, was ostensibly the one who rewrote parts of Nietzsche's writings to fit the Nazi ideology. This version of events, however, is still being discussed in [[Marxism|Marxist]] circles, with many pointing to Nietzsche's writings as always containing a kernel of [[proto-fascism]]. | ||

== Further reading == | |||

* ''[[Library:Nietzsche, the Aristocratic Rebel|Niezsche, the Aristocratic Rebel]]'' | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

[[Category:German philosophers]] | [[Category:German philosophers]] | ||

[[Category:Stubs]] | [[Category:Stubs]] | ||

<references /> | |||

[[Category:Reactionaries]] | |||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Nietzsche, Friedrich}} | |||

Latest revision as of 19:43, 11 February 2024

Friedrich Nietzsche | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 15 October 1844 Röcken, Saxony, Prussia |

| Died | 25 August 1900 (aged 55) Weimar, German Empire |

| School tradition | Atheism Irrationalism Metaphysics |

| Nationality | German |

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a reactionary German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist and a composer who was notable for exerting a profound influence in contemporary philosophy. His writing spans philosophical polemics, poetry cultural criticism, and fiction that has a fondness of displays aphorisms and irony.

The prominent elements of his philosophy included his radical critique of truth in favor of perspectivism; a genealogical critique of religion and Christian morality and a related theory of the master-slave morality; the aesthetic affirmation of life in response to both the death of God and the profound crisis of nihilism; the notion of Apollonian and Dionysian forces and a characterization of the human subject as the expression of competing wills that are collectively understood as the will of power. In his later novels, he was preoccupied with the creative powers of the individual to overcome cultural and creative mores in pursuit of new values and aesthetic health.

His bodies of work touched a wide range of topics that included art, philology, history, music, religion, tragedy, culture and science. He drew inspiration from Greek tragedy as well as figures that included Zoroaster, Arthur Schopenhauer, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Richard Wagner as well as Johan Wolfgang von Goethe.

Political views[edit | edit source]

Nietzsche said that, "This world is the will to power—and nothing besides." conflated appropriation (acquiring property) and exploitation. His views were similar to Thomas Hobbes but more reactionary due to historical context. He called socialism, "the logical conclusion of the tyranny of the least and dumbest" and the survival of the least fit. He believed that the masses, which he called "herd animals," were violently taking power away from the "noble" elements that deserved to rule. He said that humanity would collapse without slavery.[1]

Influence[edit | edit source]

Nietzsche rejected the existence of a God in favor of a supposed superhuman (Übermensch) a concept that was used by the National Socialist German Workers' Party to murder numerous Untermenschen (or subhumans) that included Jews, Poles, Slavs and other "races" the Nazis considered inferior.[2]

By many accounts, while Nietzsche himself coined the terms Übermensch and Untermensch, he did not mean them literally and only as an allegory. His sister Elizabeth, who survived him by 35 years, was ostensibly the one who rewrote parts of Nietzsche's writings to fit the Nazi ideology. This version of events, however, is still being discussed in Marxist circles, with many pointing to Nietzsche's writings as always containing a kernel of proto-fascism.

Further reading[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ John Bellamy Foster (2023-02-01). "The New Irrationalism" Monthly Review. Archived from the original on 2023-08-06.

- ↑ Ishay Landa (2023-02-08). "Aroma and Shadow: Marx vs. Nietzsche on Religion (2005)" Red Sails. Archived from the original on 2023-02-09. Retrieved 2023-02-17.