Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946): Difference between revisions

More languages

More actions

m (Ledlecreeper27 moved page Kingdom of Italy (1861–1943) to Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946)) |

(Risorgimento) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

[[Fascism]] in Italy ended in 1945, after Mussolini was killed, and his puppet state fell. The Kingdom of Italy itself was replaced by the modern [[Italian Republic|Republic of Italy]] after a referendum was held.<ref>{{News citation|newspaper=historians.org|title=The Rise and Fall of Fascism|url=https://www.historians.org/about-aha-and-membership/aha-history-and-archives/gi-roundtable-series/pamphlets/em-18-what-is-the-future-of-italy-(1945)/the-rise-and-fall-of-fascism|retrieved=2022-7-19|quote=The final collapse of fascism, though set off when Mussolini’s frightened lieutenants threw him overboard, was brought about by allied military victories plus the open rebellion of the people. Among the latter the strikes of industrial workers in Nazi-controlled northern Italy led the way. Nothing of this sort happened in Germany.}}</ref> | [[Fascism]] in Italy ended in 1945, after Mussolini was killed, and his puppet state fell. The Kingdom of Italy itself was replaced by the modern [[Italian Republic|Republic of Italy]] after a referendum was held.<ref>{{News citation|newspaper=historians.org|title=The Rise and Fall of Fascism|url=https://www.historians.org/about-aha-and-membership/aha-history-and-archives/gi-roundtable-series/pamphlets/em-18-what-is-the-future-of-italy-(1945)/the-rise-and-fall-of-fascism|retrieved=2022-7-19|quote=The final collapse of fascism, though set off when Mussolini’s frightened lieutenants threw him overboard, was brought about by allied military victories plus the open rebellion of the people. Among the latter the strikes of industrial workers in Nazi-controlled northern Italy led the way. Nothing of this sort happened in Germany.}}</ref> | ||

== History == | |||

=== Background === | |||

Italy experienced an incomplete [[bourgeois revolution]] following the [[French Revolution]]. The French overthrew the old Italian monarchies and installed liberal republican governments, which came under the rule of the Bonaparte family after [[Napoleon Bonaparte|Napoleon]]'s rise to power. Absolute monarchist rule returned in 1814 but could not restore [[feudalism]]. Italy remained divided and dominated by foreign powers despite attempted revolutions in 1820, 1831, and 1848. The [[aristocracy]] and Catholic Church largely excluded the bourgeoisie from power.<ref name=":0222">{{Citation|author=Neil Faulkner|year=2013|title=A Marxist History of the World: From Neanderthals to Neoliberals|chapter=The Age of Blood and Iron|page=152–154|pdf=https://cloudflare-ipfs.com/ipfs/bafykbzacedljwr5izotdclz23o3c5p4di4t3ero3ncbfytip55slhiz4otuls?filename=Neil%20Faulkner%20-%20A%20Marxist%20History%20of%20the%20World_%20From%20Neanderthals%20to%20Neoliberals-Pluto%20Press%20%282013%29.pdf|publisher=Pluto Press|isbn=9781849648639|lg=https://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=91CA6C708BFE15444FE27899217FBA8E}}</ref> | |||

=== Unification === | |||

The [[Kingdom of Sardinia|Kingdom of Piedmont]] under [[Victor Emanuel]] formed an alliance with [[Second French Empire|France]] and defeated [[Austrian Empire (1804–1867)|Austria]] in northern Italy in 1859. It quickly defeated the Austrian-backed monarchs of minor Italian states, and the new liberal governments of Lombardy, Parma, Modena, Emilia, Romagna, and Tuscany voted to unify with Piedmont. In May 1860, [[Giuseppe Garibaldi]] landed in Sicily and overthrew the [[Kingdom of the Two Sicilies]], unifying it with the rest of Italy. Piedmont took control of Venice with [[Kingdom of Prussia|Prussian]] support in 1866 after defeating Austria in the Austro-Prussian War. Italy annexed the [[State of the Church|Papal States]] in 1870 after [[Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte|Louis-Napoleon]]'s defeat, which removed the Pope's main protector. | |||

The Italian unification helped the country industrialize but did not improve life for the [[Peasantry|peasants]]. Garibaldi's troops killed rebellious peasants to gain support from southern [[Landlord|landlords]], who relied on mercenaries who would later become the mafia to prevent land redistribution.<ref name=":0222" /> | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 00:54, 21 January 2023

| Kingdom of Italy Regno d'Italia | |

|---|---|

| 1861–1943 | |

Motto: Credere, obbedire, combattere (Motto of the National Fascist Party) | |

| |

| Capital | Rome |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Dominant mode of production | Capitalism (decaying) |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary monarchy (1861–1922) Unitary bourgeois democracy under fascist influence (1922–1925) Unitary fascist state (1925–1943) |

• Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

• Duce | Benito Mussolini |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Area | |

• Total | 3,798,000 km² |

| Population | |

• 1936 estimate | 42,993,602 |

| Currency | Italian Lira |

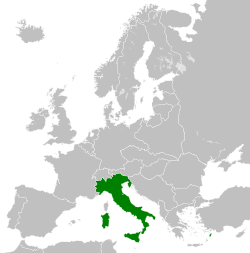

The Kingdom of Italy was a state in southern Europe. From the March on Rome in 1922 until 1943, it was under the rule of the first fascist state in history, in a historical period commonly known as Fascist Italy. While in the years from 1922-1925, the regime still maintained a liberal façade, after 1925, it soon fully formed into a militantly anti-communist dictatorship headed by Benito Mussolini.[1]

Under the reactionary and despotic government, socialist and communist organizations, trade unions, and other organs of the working class saw massive repression and deprivation, with the economy being organized in accordance to the betterment of the wealthy, at the large expense of the workers. The fascist regime also implemented the first modern privatization programs, as well as the mass cutting of social programs, in history.[2] Fascist Italy occupied Ethiopia in addition to its earlier colonies of Somalia and Eritrea.[3]

Fascist Italy allied itself with another extreme right capitalist regime, the German Reich, and joined into the Second World War after Italian forces invaded the French Republic, during the final days of the main German invasion of that nation. While seeing some territorial gains in Southern Europe in the initial part of the war, Fascist Italy would later prove itself to be an ineffectual military force, particularly in regards to the military events in Africa and Sicily.

By 1943, after the Allies had invaded mainland Italy, the long-time dictator, Benito Mussolini, was removed from power after a soft-coup. However, the Germans later returned him to power to lead a puppet state, known as the Italian Social Republic.

Fascism in Italy ended in 1945, after Mussolini was killed, and his puppet state fell. The Kingdom of Italy itself was replaced by the modern Republic of Italy after a referendum was held.[4]

History

Background

Italy experienced an incomplete bourgeois revolution following the French Revolution. The French overthrew the old Italian monarchies and installed liberal republican governments, which came under the rule of the Bonaparte family after Napoleon's rise to power. Absolute monarchist rule returned in 1814 but could not restore feudalism. Italy remained divided and dominated by foreign powers despite attempted revolutions in 1820, 1831, and 1848. The aristocracy and Catholic Church largely excluded the bourgeoisie from power.[5]

Unification

The Kingdom of Piedmont under Victor Emanuel formed an alliance with France and defeated Austria in northern Italy in 1859. It quickly defeated the Austrian-backed monarchs of minor Italian states, and the new liberal governments of Lombardy, Parma, Modena, Emilia, Romagna, and Tuscany voted to unify with Piedmont. In May 1860, Giuseppe Garibaldi landed in Sicily and overthrew the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, unifying it with the rest of Italy. Piedmont took control of Venice with Prussian support in 1866 after defeating Austria in the Austro-Prussian War. Italy annexed the Papal States in 1870 after Louis-Napoleon's defeat, which removed the Pope's main protector.

The Italian unification helped the country industrialize but did not improve life for the peasants. Garibaldi's troops killed rebellious peasants to gain support from southern landlords, who relied on mercenaries who would later become the mafia to prevent land redistribution.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ “Mussolini’s appointment as prime minister in October 1922 did not see the immediate institution of dictatorial rule. Characteristic of the means the Fascists had employed to come to power, Blackshirt squad violence helped to reduce the influence of parliamentary opposition without outlawing it altogether. From the start of 1925, a fascist parliamentary majority (elected in April 1924 partly thanks to fascist intimidation) was able to pass a series of laws which dismantled the institutions of liberal democracy. Denoting a decline in squad power, the regular police forces together with the OVRA secret police (created in 1927) were now entrusted with the task of rooting out political opposition and controlling the population, with the assistance of Fascist Party organizations (including the Militia).”

"What was the impact of Fascist rule upon Italy from 1922 to 1945?". Swansea University. Retrieved 2022-7-19. - ↑ “Italy's first Fascist government applied a large-scale privatisation policy between 1922 and 1925. The government privatised the State monopoly of match sale, eliminated the State monopoly on life insurances, sold most of the State-owned telephone networks and services to private firms, reprivatised the largest metal machinery producer, and awarded concessions to private firms to build and operate motorways. These interventions represent one of the earliest and most decisive privatisation episodes in the Western world. While ideological considerations may have had a certain influence, privatisation was used mainly as a political tool to build confidence among industrialists and to increase support for the government and the Partito Nazionale Fascista. Privatisation also contributed to balancing the budget, which was the core objective of Fascist economic policy in its first phase.”

Germa Bel (2011). The first privatisation: selling SOEs and privatising public monopolies in Fascist Italy (1922–1925), vol. 35. Cambridge Journal of Economics. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/beq051 [HUB] - ↑ Stephen Gowans (2018). Patriots, Traitors and Empires: The Story of Korea’s Struggle for Freedom: 'Imperialism' (pp. 58–59). [PDF] Montreal: Baraka Books. ISBN 9781771861427 [LG]

- ↑ “The final collapse of fascism, though set off when Mussolini’s frightened lieutenants threw him overboard, was brought about by allied military victories plus the open rebellion of the people. Among the latter the strikes of industrial workers in Nazi-controlled northern Italy led the way. Nothing of this sort happened in Germany.”

"The Rise and Fall of Fascism". historians.org. Retrieved 2022-7-19. - ↑ 5.0 5.1 Neil Faulkner (2013). A Marxist History of the World: From Neanderthals to Neoliberals: 'The Age of Blood and Iron' (pp. 152–154). [PDF] Pluto Press. ISBN 9781849648639 [LG]