More languages

More actions

(Page for Georgi Dimitrov) Tag: Visual edit |

mNo edit summary Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

When Georgi Dimitrov died in 1949, Valko Chervenkov was appointed as General Secretary of the Party. | When Georgi Dimitrov died in 1949, Valko Chervenkov was appointed as General Secretary of the Party. | ||

== References == | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Revision as of 16:51, 29 January 2023

Georgi Dimitrov (1882-1949) was a Bulgarian Marxist-Leninist revolutionary and anti-fascist freedom fighter. He led the establishment of a people's democracy and construction of socialism in Bulgaria. He was General Secretary of the Bulgarian Communist Party until his death. He also led the Communist International between 1935 and 1943.

Georgi Dimitrov Георги Димитров | |

|---|---|

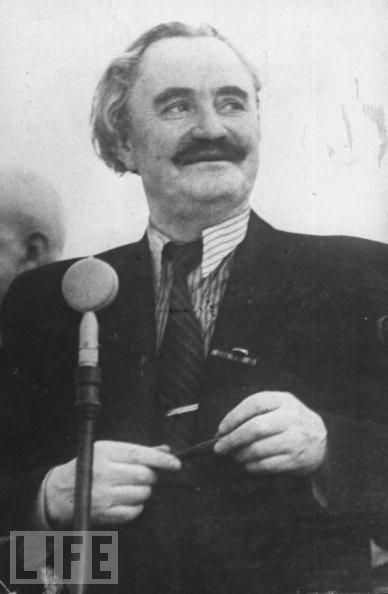

Portrait of Georgi Dimitrov | |

| Born | June 18, 1882 Kovachevtsi, Principality of Bulgaria |

| Died | July 2, 1949 (aged 67) Barvikha, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics |

| Nationality | Bulgarian |

| Political orientation | Marxism-Leninism |

Before the Revolution

Georgi Dimitrov was born in Kovachetsi, Principality of Bulgaria, his father was a worker. He fell under the influence of Dimiter Blagoev, the founder of Bulgaria's Socialist Party, a Marxist theoretician and writer of note, who occupied the first place in Bulgarian left-wing politics for a quarter of a century. Dimitrov became secretary of the Printers' Apprentice Trade Union at the age of 18 and joined the Social Democrat Party two years later. In July, 1902, the Social Democrat Party organized a conference that the party split into Bolshevik and Menshevik groups, or "Narrow" and "Broad" socialist parties as they were called. Dimitrov supported the leftist faction, the "Narrow" Socialists, and which later became the Communist Party.[1]

Early Revolutionary Activities

Dimitrov was party secretary at Plovdiv, second largest city in Bulgaria. Within a few years Dimitrov was elected to the Central Committee of the party and he held this position without interruption for 40 years. Dimitrov developed into the tough, courageous workers' leader, who organised and led strikes and was always in the thick of industrial trouble. Dimitrov had led the successful thirty-five day strike of the miners of Pernik, and was busy with predominantly trade union work, organising miners, tobacco and textile workers. In the elections of 1913, after Bulgaria had been defeated in the Balkan wars into which Tsar Ferdinand had dragged the country, the Narrow Socialists received their first electoral successes. 17 deputies were elected and amongst them Georgi Dimitrov, at 31, was the youngest member of the Bulgarian parliament. He demanded a policy of neutrality in the First World War. When the war broke out, Dimitrov denounced it as an imperialist war in which the working class should take no part. In 1915 when Bulgaria entered the war on the side of Germany, the Narrow Socialists published a manifesto opposing the decree of mobilisation. Dimitrov was arrested and imprisoned for a year and a half. In 1917, one of Georgi Dimitrov's brothers, Nikola, died in exile in Siberia. He had been arrested by the Tsar's police in 1908 for printing illegal revolutionary pamphlets in Odessa and was exiled for life to Siberia. Dimitrov was arrested again together with a large number of Pernik miners in a demonstration to celebrate Dimitrov's release from jail. The miners created a diversion which set Dimitrov free from the police, but the miners' leaders were arrested and brought to trial. In 1921 Dimitrov went to Moscow for the Third Congress of the Comintern.The Communist Party decided to launch a revolt, a revolutionary committee of three was set up, including Dimitrov, Vasil Kolarov and Gavril Guenov. September 23rd was set for the outbreak. Secret committees were set up throughout the country, arms which had long been hidden away were distributed. Early in September, the leaders were warned that Dimitrov and Kolarov and the whole Central Committee were to be arrested, so they all went "underground." On the 20th September members of the revolutionary committee for Sofia district were arrested by the police. On September 22, the insurrection broke out as planned, but Tsankoff's troops and police were well prepared. The insurgents seized many towns and districts, but were soon crushed. After six days of severe fighting, Dimitrov and Kolarov led the remnants of their battered forces across the frontier into Yugoslavia. Both were sentenced to death in absentia, both remained outside Bulgaria for 22 years, when they returned within two of months of each other, at the end of 1945. During the fighting and in the executions which followed, 30,000 workers, peasants and intellectuals lost their lives. The September revolt remained a much discussed episode in the stormy history of the Bulgarian Communist party. It cost the death or exile of many of the party's best members, including the death of another of Georgi Dimitrov's brothers, Todor, who was captured by the police and was put to death after the most horrible tortures. Dimitrov's youngest sister Elena was hounded by the police for 2 years until she eventually escaped to the Soviet Union where she met and married Valko Chervenkov who fled to the Soviet Union after the massacres of 1925. Kolarov returned to his post at the Comintern and Dimitrov went to Vienna to set up a bureau of the BCP. abroad, comprised of party exiles. With Comintern approval, Kolarov and Dimitrov called off further direct revolutionary activity in Bulgaria and asked those party leaders who were able to remain within the country to start from the bottom again and concentrate on organising workers and peasants in the legal struggle for improving their day to day life. This sage advice was disregarded, the leadership inside the country fell for the clever plot of an agent provocateur, an employee of the French Deuxieme Bureau (Secret Service) and in 1925, exploded a bomb in the Sofia Cathedral, at a moment when Tsar Boris should have been inside. The French officer obligingly telephoned Boris to remain at home that afternoon. Terrific reprisals were started immediately against the workers, another 20,000 of whom were slaughtered. These Communists that escaped the September uprising were caught in the 1925 massacre which the Sofia Cathedral attentat provoked. Leadership of the party after that was concentrated almost exclusively abroad until a party nucleus could be painfully and slowly re-established again inside the country. A Central Committee continued to meet abroad almost every year in Vienna, Moscow or Berlin, with Dimitrov and Kolarov always occupying the dominant roles in fighting against the defeatism which spread through the party after the double tragedies of 1923 and 1925.[1]

Reichstag Fire

Dimitrov was in Berlin in 1933, when the flames of the burning Reichstag served Hitler as the bomb plot in Sofia had served Tsar Boris. Not content with banning the German Communist Party and arresting all its leaders, including the Communist deputies in the Reichstag, Hitler wanted to prove to the world he was forced to these measures by the provocations of international Communism. The scapegoat was none other than the Bulgarian Communist leader Georgi Dimitrov. The trial held at Leipzig six months after the firing of the Reichstag was intended to be Hitler's supreme stage piece against Communism. But he had reckoned without the magnificent audacity, courage and wit of Dimitrov – and of the efforts of Vasil Kolarov abroad in rallying international support for the Bulgarian Communist leader. Dimitrov's behaviour in Court won him the admiration of the whole world and raised the prestige of Communists enormously. His audacious replies to an empurpled Goering, despite the latter's authority as Minister-President, were commented on in the world press. Dimitrov had been kept in chains and half-starved for six months before he was brought into court. He was warned that his only chance for mercy would be to admit his guilt. The trial provided the sensational publicity Goebbels had promised, but the very opposite type of publicity he had expected. Trained police witnesses forgot their lines when Dimitrov began to cross-question them. Dimitrov not only denied his own guilt but nailed the Nazi leaders themselves as the real culprits and more precisely named Herman Goering as chief incendiary. When his questions got too acute, the court president closed the session or had Dimitrov removed from the Court, or refused to allow him to continue his questioning.[2]

World War II and the People's Uprising of 9 September

The lessons of 1923 had not been lost on Dimitrov. On his initiative in 1942, the Fatherland Front was founded inside Bulgaria, a union of workers and peasants organisations, embracing every member of the community, prepared to take up arms against the Nazis and the Bulgarian Fascists, it was later to become the basis for all political activity in Bulgaria. The Fatherland Front overthrew the fascist government in 1944 with the help of the Soviet Red Army. Dimitrov returned to Bulgaria in 1945.

People's Republic of Bulgaria

In 1946, the People's Republic of Bulgaria established. In 1945, the Fatherland Front was having difficulties. British and American efforts were directed to splitting up the organisation and gaining control of any opposition party which they could persuade to leave the Front. Both Dimitrov and Kolarov were sick men and they knew they had a limited time to weld together a party and a government capable of consolidating the great gains that had been made, and leading the country on to socialism. They were determined that this time there should be no Tsankoff coup d'etat and that there should be no weak links in the party leadership which would enable a new Tsankoff to gain a footing.

Despite all the difficulties, Dimitrov led Bulgaria towards building socialism and transforming it into a secular republic. The 1947 Constitution was adopted and the ethnic problems in Bulgaria were resolved.

Death

When Georgi Dimitrov died in 1949, Valko Chervenkov was appointed as General Secretary of the Party.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Wilfred G. Burchett (1951). Peoples' Democracies: 'The Life of Georgi Dimitrov – Part I'. Australia: World Unity Publications.

- ↑ Wilfred G. Burchett (1951). Peoples' Democracies: 'The Life of Georgi Dimitrov – Part II'. World Unity Publications.