More languages

More actions

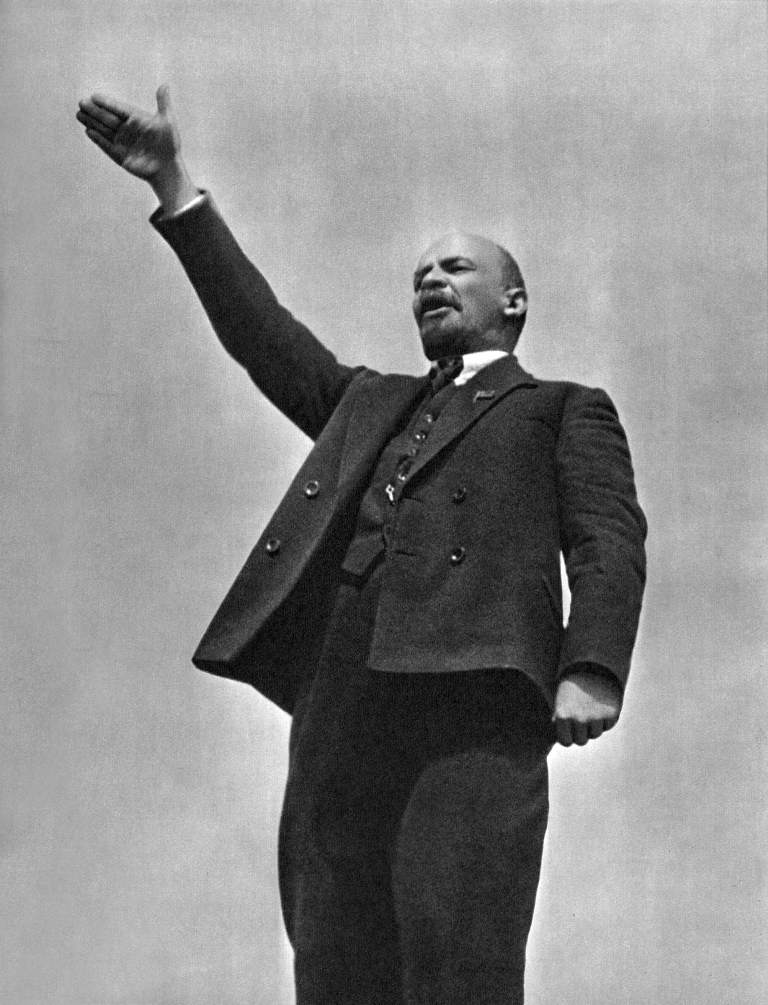

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin Владимир Ильич Ленин | |

|---|---|

Photo of comrade Lenin | |

| Born | Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov 22 April 1870 Simbirsk, Russian Empire |

| Died | 21 January 1924 (aged 53) Gorki, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Nationality | Russian Soviet |

| Political orientation | Marxism (developed what is now known as Marxism-Leninism) |

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov[a] (22 April 1870 — 21 January 1924), also known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary leader, political and economic theorist, and philosopher. He is considered one of the most important figures of the 20th century especially as it relates to the socialist movement. Author of several books contributing to Marxist theory, Lenin was responsible for the development of the understanding of the imperialist phenomenon in capitalist mode of production and was a key figure in the 1917 revolution that led to the establishment of the Soviet Union.

Lenin's political and theoretical activity, his writings of the 1890s and the beginning of the 20th century, his resolute struggle against opportunism and revisionist attempts to distort Marxist theory, his struggle for the creation of a revolutionary political party is considered the Leninist contribution to Marxism, now commonly referred to as Marxism-Leninism.

Life and work

Early life (1870–1888)

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov was born in Simbirsk[b] on 22 April 1870[c], the fourth of eight children of Ilya Ulyanov, a respected figure in public education and son of former serf, and Maria Alexandrovna, a woman who came from a family of nobility background.[1] Although Lenin's father was not a revolutionary himself, he shared progressive views and opposed autocracies, and both his father and mother contributed greatly with his intellectual upbringing. Besides his mother and father, a big intellectual influence on Lenin was his brother Alexander, who first introduced him to Marxist literature.[2]

Lenin's youth and childhood coincided with a reactionary period in Russia, when civilians were commonly arrested for expressing criticism of the czarist regime.[2] In May 1887, when Lenin was 17 years old, his brother Alexander Ulyanov was publicly executed for an attempt to assassinate the tzar Alexander III, and event which had an impact in Lenin's radicalization towards revolutionary action.[3]

Lenin was admitted to the Faculty of Law at Kazan University in 13 August 1886, and a month later he joined the Samara-Simbirsk Fraternity, a student society, at the time prohibited by the University Statutes and punishable by expulsion.[2][4] A year after he began his studies, he joined student campaigns and demonstrations demanding that student societies be permitted, that students who had been expelled be reinstated and those responsible for their expulsion be called to account.[2] As a result of participation in the student demonstrations, on December 1887, Lenin was arrested, expelled from University and exiled to a nearby village for one year, becoming under strict police surveillance since then.[2]

Throughout his exile in the village of Kokushkino, Lenin studied extensively political economy works and other literature. Later in his life, he wrote about this period: “I don't think I ever afterwards read so much in my life, not even during my imprisonment in St. Petersburg or exile in Siberia, as I did in the year when I was banished to the village from Kazan; I read voraciously from early morning till late at night.”[2]

In the autumn of 1888, Lenin was permitted to return to Kazan and shortly after returning, but unable to readmit to the university. He was also prohibited from attending universities abroad. Back in Kazan, he joined a Marxist study-circle organized by Nikolai Fedoseyev, beginning his political and revolutionary activities. It was during this period of 1888–89 that Lenin studied for the first time Karl Marx's Capital, vol. I.[2]

Early revolutionary activities (1889–1895)

In May 1889, the Ulyanov family moved to a village next to the city of Samara, with Lenin narrowly escaping another arrest by the secret police, which arrested and imprisoned members of Fedoseyev Marxist study-circles of Kazan a month later. In Samara, Lenin earned a living by giving lessons. Considering he was prohibited from attending university, Lenin sent several applications requesting permission to pass his university examinations without attending lectures, until 1890, when he received the permission to do so, along with the task of studying for 18 months independently. After hard work and intense study schedule, he took his examinations in 1891, achieving the highest marks in all subjects, receiving a first-class diploma.[5]

Lenin began to practice law in the Samara Regional Court, and he appeared for defense in court about twenty times during the period of 1892–93. His legal practice, however, was secondary only to diligently studying Marxism to prepare himself for revolutionary work. In 1892, Lenin organized the first Marxist circle in Samara. The study group focused on the works of Marx and Engels, the works of Plekhanov and others.[5] Lenin's legal practice enriched his knowledge of the real world, as this enabled him to see concrete examples of class struggle from the perspective of the economically disenfranchised and the limits of the bourgeois law apparatus.[4]

In 1893, Lenin wrote his earliest theoretical work titled New economic developments in peasant life,[d] an analysis of Russia's economy based on data and statistics on peasant farming.[5] During that time, Lenin corresponded with Nikolai Fedoseyev and exchanged views on Marxist theory and the economic and political developments of Russia.[5] He had a deep affection for their friendship, and years later he wrote: "Fedoseyev played a very important role in the Volga area and in certain parts of Central Russia during that period; and the turn towards Marxism at that time was, undoubtedly, very largely due to the influence of this exceptionally talented and exceptionally devoted revolutionary."[6]

In August 1893, Lenin went to St. Petersburg, where he attended to several Marxist circle meetings, where the sharply criticized the liberal Narodniks, serving as a basis for Lenin's 1894 book What the “friends of the people” are and how they fight the social-democrats?, which was illegally distributed in 3 parts throughout cities of Russia, laying down the theoretical foundation for the program and tactics of the Russian revolutionary social-democrats.[7][4] It was during this period that Lenin first met Nadezhda Krupskaya, which was working as a teacher free of charge for workers.[8]

Establishment of a united Marxist organization and arrest (1895–1897)

In March 1895,[9] Lenin attended a conference in St. Petersburg of members of the social-democratic groups of St. Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev and Vilno. The conference discussed the question of changing over from the propaganda of Marxism in narrow circles to mass political agitation, and of publishing popular literature for the workers and establishing close contact with them. It was decided to send two representatives abroad, and Lenin was one of them.[10]

From May to September, Lenin traveled abroad to meet the social-democrats in exile, mainly Plekhanov, in Berlin, Lenin first met Wilhelm Liebknecht a German social-democrat and in Paris, Lenin met Paul Lafargue, Marx's son-in-law and socialist militant.[11][12][4] In the occasion of Friedrich Engels' death, in August 5, 1895, Lenin wrote a small pamphlet highlighting Engels' contribution to the proletarian cause.[13] In the same year, the Marxist circles of St. Petersburg united into a single political organization under Lenin's leadership. In December this organization adopted the name of League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class.[e][10] The organization had been active months earlier in agitating workers through pamphlets and participated in strikes, which led to the arrest of Lenin and other leaders of the League in 20 December, 1895. Lenin was accused of "crimes against the state" and was given fourteen months of solitary confinement followed by three years of Siberian exile.[10][4]

During his time in prison, Lenin continued to carry on his revolutionary work. He quickly found ways and means of establishing contacts with comrades who were not arrested and through them directing the activities of the League. Inside his cell, he managed to write the draft program for the first congress of the League and began to write and research for his book The development of capitalism in Russia evading censorship by using milk as invisible ink, which would reveal the writing once warmed or dipped in hot water.[10][14] Krupskaya was able to exchange letters with Lenin by describing herself as Lenin's fianceé, and through her he maintained communication with the members of the League.[15]

Siberian exile (1897–1900)

After more than fourteen months of imprisonment Lenin was sentenced to three years in exile in the village of Shushenskoye in Eastern Siberia under police surveillance. The sentence was announced to him on February 13, 1897.[16] In a 1897 letter to his mother and sister during his exile, Lenin asked them to bring him works written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published in French, The poverty of philosophy, Critique of Hegel's philosophy of right, and a chapter of Anti-Dühring.[17] Krupskaya, who was in prison since August 1896 in the same case as Lenin, received permission to join Lenin in Shushenskoye by describing herself as his fianceé in December 1897,[18] and in May 1898 she finally arrived, marrying Lenin a month later.[19][20]

During his time in exile, Lenin developed two main works, The tasks of the Russian social-democrats, where he presented the practical works of the Russian social-democrats as spreading the teachings of scientific socialism and fighting against czarism,[21] and The development of capitalism in Russia, a thorough and profoundly researched study on the economic development of Russia published in 1899 under a pseudonym. The book provided, through extensive analysis and ample statistical evidence, a well-reasoned argument in support of a revolutionary alliance between working class and peasantry, considering Imperial Russia's historical conditions, and showed that a process of economic differentiation had begun among the peasants, a few of which were becoming kulaks, or the rural bourgeoisie.[22]

The first congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) was held in March, 1898 in Minsk, which founded the party and showed that the organization was growing withstanding the blows it received from the arrest of its leaders.[23] Although the congress and its Manifesto were in many respects lacking,[24] at the time, Lenin described the foundation of the RSDLP as "the biggest step taken by the Russian working-class movement in its fusion with the Russian revolutionary movement."[25] With the publication of The development of capitalism in Russia in 1899, Lenin begun a struggle against the anti-Marxist ideologues known at the time as the Narodnik and the "legal Marxists",[26] represented especially by Bernstein, whose ideas Lenin described as "an attempt to narrow the theory of Marxism, to convert the revolutionary workers' party into a reformist party".[27]

The idea of creating of a single, united Marxist party in Russia occupied a central place in Lenin's writings at the time of his exile in Siberia. Lenin wrote three articles for the Workers' Gazette,[f] which had been adopted as the official newspaper organ of the RSDLP, on the question of founding a Marxist party, Our programme,[28] Our immediate task,[29] An urgent question.[30] These articles were published only in 1925, because the Central Comittee was arrested and the newspapers organ of the RSDLP was destroyed.[31] At the end of his exile, Lenin didn't have his term prolonged, but was prohibited from residing in university cities or large industrial centers. Lenin chose a place of residence close to St. Petersburg.[32]

Revolutions in Russia (1905–1917)

Soviet government (1918–1923)

Declining health and death (1923–1924)

Library works

- (1902) What is to be done?

- (1905) Two tactics of social-democracy in the democratic revolution

- (1908) Materialism and empiriocriticism

- (1913) The three sources and three component parts of Marxism

- (1916) Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism

- (1917) The state and revolution

- (1918) The proletarian revolution and the renegade Kautsky

- (1920) “Left-wing” communism, an infantile disorder

References

- ↑ Tamás Krausz (2015). Reconstructing Lenin: an intellectual biography: 'Family'. ISBN 9781583674499 [LG]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Childhood and youth. The beginning of revolutionary activity; The shaping of revolutionary views'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ Robert Service (2000). A biography of Lenin: 'Deaths in the family'. ISBN 9780333726259 [LG]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Tamás Krausz (2015). Reconstructing Lenin: an intellectual biography: 'Who was Lenin?; Education'. ISBN 9781583674499 [LG]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Childhood and youth. The beginning of revolutionary activity; The Samara period'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ Vladimir Lenin (1922). A few words about N. Y. Fedoseyev. [MIA]

- ↑ Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Leader of the revolutionary proletariat of Russia; The ideological defeat of Narodism'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Leader of the revolutionary proletariat of Russia; Among the St. Petersburg Proletariat'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ “2 or 3 March: Lenin takes part in a meeting of members of social democratic groups from St Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev and Vilno. Passing from propaganda work in Marxist circles to mass agitation work is debated.”

Gerda Weber & Hermann Weber (1974). Lenin: life and works: '1895' (p. 7). [LG] - ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Leader of the revolutionary proletariat of Russia; The League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ “15 May-8 June: Lenin travels to Switzerland; he meets Potresov in Geneva and travels with him to see Plekhanov who is on holiday in the mountain village of Les Ormonts, near Les Diablerets. [...]

Before 8 June: Lenin travels to Paris and gets to know Paul Lafargue, Karl Marx's son-in-law, there. [...]

14 September: In a letter to Wilhelm Liebknecht, Plekhanov recommends Lenin as 'one of our best Russian friends' and requests that Lenin be received because of an 'important matter' as he is returning to Russia. Lenin visits Wilhelm Liebknecht in Charlottenburg between 14-19 September.”

Gerda Weber & Hermann Weber (1974). Lenin: life and works: '1895' (pp. 7-9). [LG] - ↑ “In Europe in 1895, he met the elders of Russian Marxism: Plekhanov and Axelrod in Switzerland, Paul Lafargue (Marx’s son-in-law) in Paris and Wilhelm Liebknecht in Berlin.”

Tariq Ali (2017). The dilemmas of Lenin: 'Terrorism and utopia; The younger brother' (pp. 44-45). [LG] - ↑ Vladimir Lenin (1895). Friedrich Engels. [MIA]

- ↑ “They came written in milk every Saturday, which was book-receiving day. A glance at the secret mark would tell you that the book contained a message. Hot water for tea would be handed round at six o'clock, and then the wardress would conduct the non-political criminals to church. By that time you bad the letter cut up in strips, and your tea brewed, and the moment the wardress went away you would begin dipping the strips in the hot tea to develop the text.”

Nadezhda Krupskaya (1933). Reminiscences of Lenin: 'St. Petersburg'. [MIA] - ↑ “So-and-so had no one coming to visit him – it was necessary to get him a "fiancee": or so-and-so had to be told through visiting relatives to look for letters in such-and-such a book in the prison library, on such-and-such a page; another needed warm boots, and so on.”

Nadezhda Krupskaya (1933). Reminiscences of Lenin: 'St. Petersburg'. [MIA] - ↑ Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile' (p. 51). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ “I should like to have Saint-Simon and also the following books in French:

K. Marx. Misère de la philosophie. 1896. Paris.

Fr. Engels. La force et l’ économic dans le développement social.

K. Marx. Critique de la philosophie du droit de Hegel. 1895.

all these are from the “bibliothèque socialiste internationale” where Labriola came from.

All the best,

V. U.”

Vladimir Lenin (1897). December 21, 1897 letter to his mother and sister. [MIA] - ↑ “I was banished to the Ufa Gubernia for three years, but obtained a transfer to the village of Shushenskoye in the Minusinsk Uyezd, where Vladimir Ilyich lived, by describing myself as his fiancee.”

Nadezhda Krupskaya (1933). Reminiscences of Lenin: 'St. Petersburg'. [MIA] - ↑ “Krupskaya arrived in Shushenskoye early in May 1898 together with her mother Yelizaveta Vasilyevna. Lenin and Krupskaya were married on July 10. They set up house together, started a small kitchen garden, planted flowers and hops in the yard. The young couple lived in peace and harmony.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile; In Shushenskoye' (p. 54). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “The name of his love, Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya—who was arrested in the same case as Vladimir Ilyich albeit much later, on 12 August 1896—came up often in his letters. In his letters from 19 October, 10 December, and 21 December 1896 (from Shusha to Moscow, addressed to his mother, Manya, and Anyuta), he wrote to his relatives that Nadezhda Konstantinovna might join him soon, for she had received permission to choose Shushenskoye instead of northern Russia”

Tamás Krausz (2015). Reconstructing Lenin: an intellectual biography: 'Who was Lenin?; The personality of Lenin as a young man in exile and as an émigré'. ISBN 9781583674499 [LG] - ↑ “The object of the practical activities of the Social-Democrats is, as is well known, to lead the class struggle of the proletariat and to organize that struggle in both its manifestations: socialist [...], and democratic [...]

The socialist activities of Russian Social-Democrats consist in spreading by propaganda the teachings of scientific socialism, in spreading among the workers a proper understanding of the present social and economic system, its basis and its development, an understanding of the various classes in Russian society, of their interrelations, of the struggle between these classes, of the role of the working class in this struggle, of its attitude to wards the declining and the developing classes, towards the past and the future of capitalism, an understanding of the historical task of international Social-Democracy and of the Russian working class. [...]

Let us now deal with the democratic tasks and with the democratic work of the Social-Democrats. Let us repeat, once again, that this work is inseparably connected with socialist activity. [...] Simultaneously with the dissemination of scientific socialism, Russian Social-Democrats set themselves the task of propagating democratic ideas among the working class masses; they strive to spread an understanding of absolutism in all its manifestations, of its class content, of the necessity to overthrow it, of the impossibility of waging a successful struggle for the workers’ cause without achieving political liberty and the democratization of Russia’s political and social system.”

Vladimir Lenin (1898). The tasks of the Russian social-democrats. [MIA] - ↑ Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile; The development of capitalism in Russia'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile; In Shushenskoye' (p. 54). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ “The First Congress of the R.S.D.L.P. was attended by only nine persons. Lenin was not present because at that time he was living in exile in Siberia. The Central Committee of the Party elected at the congress was very soon arrested. The Manifesto published in the name of the congress was in many respects unsatisfactory. It evaded the question of the conquest of political power by the proletariat, it made no mention of the hegemony of the proletariat, and said nothing about the allies of the proletariat in its struggle against tsardom and the bourgeoisie.”

Vilhelm Knorin, Pyotr Pospelov & Yemelyan Yaroslavsky (1938). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The struggle for the creation of a social-democratic labour party in Russia (1883–1901); Lenin's struggle against Narodism and "legal Marxism." Lenin's idea of an alliance of the working class and the peasantry. First congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party'. [MIA] - ↑ Vladimir Lenin (1899). A retrograde trend in Russian social-democracy. [MIA]

- ↑ Vilhelm Knorin, Pyotr Pospelov & Yemelyan Yaroslavsky (1938). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The struggle for the creation of a social-democratic labour party in Russia (1883–1901); Lenin's struggle against Narodism and "legal Marxism." Lenin's idea of an alliance of the working class and the peasantry. First congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party'. [MIA]

- ↑ “The notorious Bernsteinism—in the sense in which it is commonly understood by the general public, and by the authors of the Credo in particular—is an attempt to narrow the theory of Marxism, to convert the revolutionary workers’ party into a reformist party. As was to be expected, this attempt has been strongly condemned by the majority of the German Social-Democrats. Opportunist trends have repeatedly manifested themselves in the ranks of German Social-Democracy, and on every occasion they have been repudiated by the Party, which loyally guards the principles of revolutionary international Social-Democracy. We are convinced that every attempt to transplant opportunist views to Russia will encounter equally determined resistance on the part of the overwhelming majority of Russian Social-Democrats.”

Vladimir Lenin (1899). A protest by Russian social-democrats. [MIA] - ↑ “It made clear the real task of a revolutionary socialist party: not to draw up plans for refashioning society, not to preach to the capitalists and their hangers-on about improving the lot of the workers, not to hatch conspiracies, but to organize the class struggle of the proletariat and to lead this struggle, the ultimate aim of which is the conquest of political power by the proletariat and the organization of a socialist society.”

Vladimir Lenin (1899). Our programme. [MIA] - ↑ “It is the task of the Social-Democrats, by organizing the workers, by conducting propaganda and agitation among them, to turn their spontaneous struggle against their oppressors into the struggle of the whole class, into the struggle of a definite political party for definite political and socialist ideals. This is some thing that cannot be achieved by local activity alone.”

Vladimir Lenin (1899). Our immediate task. [MIA] - ↑ “The main objection that may be raised is that the achievement of this purpose first requires the development of local group activity. We consider this fairly widespread opinion to be fallacious. We can and must immediately set about founding the Party organ—and, it follows, the Party itself—and putting them on a sound footing. The conditions essential to such a step already exist: local Party work is being carried on and obviously has struck deep roots; for the destructive police attacks that are growing more frequent lead to only short interruptions; fresh forces rapidly replace those that have fallen in battle. The Party has resources for publishing and literary forces, not only abroad, but in Russia as well. The question, therefore, is whether the work that is already being conducted should be continued in “amateur” fashion or whether it should be organised into the work of one party and in such a way that it is reflected in its entirety in one common organ.”

Vladimir Lenin (1899). An urgent question. [MIA] - ↑ “While in exile Lenin gave much thought to the plan of founding a Marxist party. He expounded it in his articles "Our Programme", "Our Immediate Task" and "An Urgent Question" written for Rabochaya Gazeta (Workers' Gazette) . In the autumn of 1 899, Lenin accepted an offer to be the editor of this newspaper and then to contribute to it. The paper was recognised by the First Congress of the R.S.D.L.P. as the official organ of the Party, but the police closed it shortly after. In 1899, an attempt was made to resume publication. But the attempt failed and Lenin's articles remained unpublished. They first saw light of day in 1925.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile; The plan for a Marxist party' (pp. 65-66). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “At the end of his exile Lenin’s thoughts were occupied with the problem of putting into effect his plan for creating a revolutionary- proletarian party. Lenin looked forward eagerly to the day when his term of exile would be over, fearing that the tsarist authorities, as often happened, might prolong his term. He became nervous, slept poorly and lost weight. He longed to be doing active work.

Luckily, Lenin’s apprehensions proved groundless – his term was not prolonged. Early in January 1900, the Police Department sent Lenin a notice to the effect that the Minister of the Interior had forbidden him to reside in the capital and university cities and large industrial centres after the completion of his term of exile. Lenin chose Pskov as his place of domicile to be nearer to St. Petersburg.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile; The plan for a Marxist party' (pp. 67-68). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

Notes

- ↑ Russian: Владимир Ильич Ульянов

- ↑ Russian: Симбирск

The city of Simbirsk was the administrative center of Simbirsk Governorate, which was one of the administrative divisions of the Russian Empire. The city is now known as Ulyanovsk, of the Ulyanovsk Region in the Russian Federation, in honor of Lenin. - ↑ Current calendar (Gregorian)

- ↑ The article is available on Marxists Internet Archive.

- ↑ Russian: Союз борьбы за освобождение рабочего класса, lit. Union of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class

- ↑ Russian: Рабочая Газета