More languages

More actions

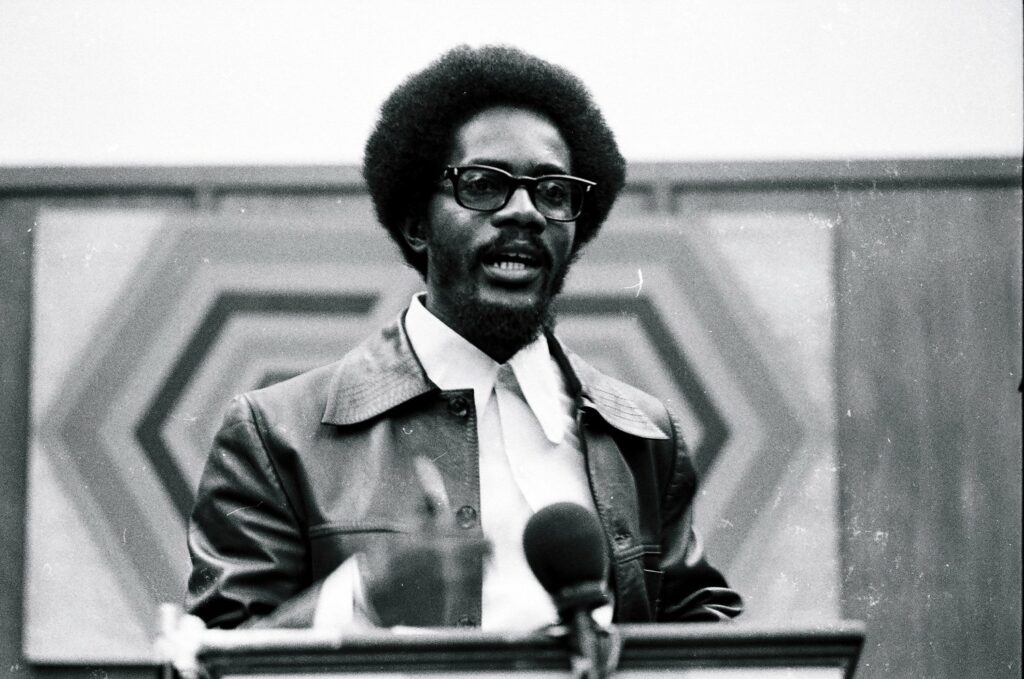

Walter Rodney | |

|---|---|

Walter Rodney | |

| Born | 23 March 1942 Georgetown, British Guiana |

| Died | 13 June 1980 Georgetown, Guyana |

| Cause of death | Assassination by bomb |

Walter Rodney was a Guyanese Marxist and anti-imperialist historian an political activist and academic. His work remains highly influential, and significantly contributed to Pan-Africanism and the Black Power movement, while providing a highly influential analysis of colonialism and underdevelopment in Africa. He produced significant works contributing to the understanding of African, Carribean and Guyanese history.

Early life and Education[edit | edit source]

Walter Rodney was born in 1942 into a working-class family in Georgetown, Guyana.His father, Edward Percival, was a tailor who worked largely for himself. However, when work was scarce, he would accept lower-paying work for a weekly wage at a small outlet in Georgetown. Walter Rodney's mother, Pauline, worked from home as a seamstress. Walter’s father, Edward, had travelled for work in the 1930s to Curaçao—a Dutch-held Caribbean island off the coast of Venezuela—before joining the nationalist movement in Guyana led by union activist Cheddi Jagan. When Walter was eleven years old, his father encouraged him to participate in the 1953 election campaign, leafleting and canvassing for the People’s Progressive Party (PPP) (the British Government labelled this a Marxist movement and attempted to invalidate it by suspending a constitution that allowed limited self-rule in Guyana) . Following the PPP’s victory in the 1953 elections (taking 18 of the 24 elected seats in the House of Assembly, resulting in Jagan becoming Chief Minister), Walter Rodney was among the first from working-class homes to be selected for a new scholarship program initiated by the party.[1]

He attended Queens College in Georgetown where he won an open scholarship to the University of the West Indies to read history. In secondary school he distinguished himself in extra-curricular activities. He was in the student cadet corps, as well as being a high jumper and a debater.[2]

He attended the University College of the West Indies by the age of 17 in 1960, (in Jamaica) and was awarded a first-class honours degree in history in 1963. Returning from a a trip to Cuba in January 1962 as a group of three students, they had with them, as the Jamaican intelligence service recorded, a “considerable amount of Communist literature and subversive publications of the IUS, including Che Guevara’s ‘Guerrilla Warfare.’” The books were seized by customs and temporarily held. In a student newsletter, Rodney denounced the authorities for seizing what he described as a “quite innocuous” gift from the Cubans. He engaged in activism and labour agitation, including organising a strike of the staff of the UWI in May of 1962.[1]

In August 1962, Walter travelled to Leningrad to attend the annual meeting of the IUS (International Union of Students).[1] Here, he recalls his experiences in the Soviet Union very fondly, being impressed at the books being sold on the streets, the lack of a sharp social division in cultural activities (such as visiting the opera), and the use of passenger air travel.[3] He was also impressed by his visit to Cuba, recalling that:

"Travelling to Cuba was also another important experience, because I was with Cuban students and I got some insight at an early period into the tremendous excitement of the Cuban Revolution. This was 1960, just after the victory of the revolution. One has to live with a revolution to get its full impact, but the next best thing is to go there and see a people actually attempting to grapple with real problems of development. Cuba was a different dimension from the Soviet Union, because the Russians had made their revolution and were moving along smoothly. But the Cubans were up and about, talking and bustling and running and jumping and really living the revolution in a way that was completely outside of anything that one could read anywhere or listen to or conceptualize in an island such as Jamaica, which is where I was still. The Cuban experience was very good. I was fortunate in visiting Cuba twice, only for brief periods, but long enough to get that fire and dynamic of the Cuban revolution."[3]

After pausing to complete his studies, he returned to activism as a “sympathizer” of the Young Socialist League in 1963, a left-wing grouping within the opposition People’s National Party (PNP). He moved to London in September, 1963. There, he immersed himself in the communities of colonial peoples and migrants, attended meetings of the West African Student's Union (WASU) with his future wife, debated around Hyde Park, and began to move towards Marxism "as a lived practice". He also travelled to Lisbon, Seville and Rome to conduct archival research for his PhD intermittently.[1]

He earned a PhD in African History on July 5th, 1966 (some hours after his first child was born, Shaka Rodney. Two of his children, Kanini and Asha were born in Tanzania.)[1] at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, at the age of 24. Rodney’s thesis was published by Oxford University Press as A history of the Upper Guinea coast 1545-1800. [4] Before he finished his Doctorate in 1966 he married Patricia Henry from Guyana, who was studying in England. [2]

While in London, he organized a Marxist study group that met once a week,[5] over the course of three years with C.L.R James and his wife Selma James. The decision to organise reading circles independently was one of circumstance, as he found the political climate of the UK left to be inhospitable, offering no avenue for marxist development. He denounced British Trotskyism as "downright foolish", "inarticulate" and "racist", as well as organisationally incapable or unwilling to organize workers. Additionally, he criticised The New Left Review for its paternalism, latent racism, facileness and lack of depth and seriousness.[3]

He published journal articles in the Journal of African History on 'Portuguese Attempts At Monopoly on the Upper Guinea Coast 1580-1650', in 1966, 'A Reconsideration of the Mane Invasions of Sierra Leone', in 1967, and 'African Slavery and Other Forms of Social Oppression On The Upper Guinea Coast In The Context of the Atlantic Slave Trade', in 1966.[2]

Political Life and Scholarship[edit | edit source]

Tanzania (1966-1968)[edit | edit source]

Rodney began teaching in Tanzania in 1966. Applying to the British Ministry of Overseas Development, which advertised in England for positions all over Africa, he began teaching at the University of Dar Es Salaam in July 1966.[3] In 1967, Rodney prepared for a new, first-year course, “History: African Outline.” In his suggestions and recommendations to students, they were equally encouraged to read Frantz Fanon (as “essential theoretical reading”) but also "mainstream" accounts like those of Elliot Berg and Jeffrey Butler on trade unions in “tropical Africa.”[1]

He also immersed himself into the debates surrounding the establishment of Tanzanian socialism (Ujamaa) after the Arusha Decleration, also requesting a salary decrease in response to students hosting a demonstration against the loss of their supposed privileges in December 1966. Additionally, he was in organised study groups (studying works of Paul Baran, Samir Amin, Frantz Fanon and Paul Sweezy), debated and was involved in radical student politics and in the formation of the University Students' African Liberation Front, or USARF (which started as the Socialist Club) and the TANU Youth League i,e. the Youth League of the Tanganyika African Nation Union, in support of Julius Nyereres injunction to debate socialism in 1967.[1]

The Rodneys also met some of their lifelong comrades there, such as Marjorie Mbilinyi and Simon Mbilinyi. He returned to the University of the West Indies to teach in January of 1968.[1]His connections brought the likes of CLR James, Kwame Ture (then still Stokely Carmicheal) and Guyanese politician Cheddi Jagan to speak on USARF platforms.[6]

Jamaica (1968-1968)[edit | edit source]

He lectured in the History Department at the University of the West Indies starting January 1968. He spent much of his free time with the Rastafarians in sessions called 'Groundings'. [2]

In Jamaica, Rodney initially came to “security notice” in June 1961. Along with two other UWI students, he agreed to attend a meeting in Moscow, the invitation having come from the Prague-based International Union of Students (IUS). He declined this offer initially, however he went to Moscow a year later. Following and during his trip to Cuba, the Jamaican security reckoned that Rodney’s contacts in Cuba extended to the highest level:

“There is reason to believe that whilst in Cuba Rodney and his companions were visited in the Hotel by Castro himself.”[7]

On arrival to England, Rodney’s intelligence file indicates:

“Whilst in England he stayed with his brother Edward Rodney [and accompanied Edward] to what London sources [presumably British intelligence, or else contacts on the ground] termed ‘meetings of various extremist groups.’”

In particular, Rodney came to “notice” in 1965 on account of his “association with Richard Hart and other known West Indian Communists in London.”[7] Upon his re-entry to Jamaica, he started organizing from February 1968, however remaining unimpressed with the two major left-wing parties in Jamaica, the opposition People’s National Party (PNP)- an organisation he previously sympathized with via its youth league, the Young Socialist League - and the New World Group (NWG), which he described as “an organization of ‘armchair’ left wing intellectuals” that operated throughout the Anglophone Caribbean.[7] He therefore opted to connect directly to the masses via the Rastafarian movement. He gives an account of this as follows:

“I sought them out where they lived, worked, worshipped, and had their recreation. In turn, they ‘checked’ me at work or at home, and together we ‘probed’ here and there, learning to recognise our common humanity. Naturally, they wanted to know what I stood for, what I ‘defended.’” (...) “Some of my most profound experiences have been the sessions of reasoning or ‘grounding’ with black brothers, squatting on an old car tire or a rusty five gallon can.”[7]

When he attended the Black Writers' Conference in Montreal, Canada in October 1968, Hugh Shearer's Jamaica Labour Party Government banned him from returning to his job at the University.[2] On 15 October 1968, the government of Jamaica, led by prime minister Hugh Shearer, declared Rodney persona non grata. Walter Rodney gives his following analysis of the reason behind this:

"These men serve the interests of a foreign, white capitalist system and at home they uphold a social structure which ensures that the black man resides at the bottom of the social ladder. He is economically oppressed and culturally he has no opportunity to express himself. That is the situation from which we move."[8]

and

“It was this ‘grounding’ with my black brothers that the regime considered sinister and subversive.”[7]

The decision to ban him from ever returning to Jamaica and his subsequent dismissal by the University of the West Indies caused protests by students and the poor of Kingston that escalated into a riot, known as the Rodney Riots, resulting in six deaths and causing millions of dollars in damages.[7] The riots and revolts in Kingston subsequent to his banning showed the deep respect that he had gained in the eight months period that he lived in Jamaica. Rodney interprets this as follows:

"Let us stop calling it student riots. What has happened in Jamaica is that the black people of the city of Kingston have seized upon this opportunity to begin their indictment against the Government of Jamaica (...). This is part of the whole social malaise, that is revolutionary activity."[8]

His sessions with the Rastafarians were published in a pamphlet entitled Groundings With My Bothers.[2]

Tanzania (1969-1974)[edit | edit source]

In 1969, Rodney returned to the University of Dar es Salaam. He was promoted to senior lecturer there in 1971 and promoted to associate professor in 1973.[1] In Tanzania, he thought history and political science at the University of Dar es Salaam from 1969 to 1974. He reconnected with the socialist students he had met during his first stay in 1966.[6] Upon his return in 1969, the USARF had gained new members, Karim Hirji being among them. He got Rodney to write the first article for the group’s magazine Cheche on African labour (Cheche took its name from Lenin’s newspaper Iskra. Both words mean ‘spark’ – in Swahili and Russian respectively)[6], entitled "African Labour Under Capitalism and Imperialism".[9] Vijay Prashad describes the relevance of this text as follows:

"[This text] attempted to chart the current motion of the African working-class and revolutionary sections of the peasantry. Rodney was interested in the objective and subjective situation of the African workers: How was capitalism across the continent organized, what kind of labor organization was possible as a consequence, what was the general sensibility of the African workers (both the proletariat and the peasantry) and what was the relationship between African workers and the anti-imperialist national liberation movements and regimes that had taken hold across the continent? These were the kinds of questions raised by Rodney in this period—questions stimulated by his turn fully into Marxism, which was deeply inflected by his awareness of the situation in the Third World and its particular ground for a Marxist analysis."[9]

By 1970, Rodney stood at the heart of the debates concerning African underdevelopment that occurred almost every night at the University. Rodney debated a TANU Cabinet Minister on Tanzania’s economic direction. He also debated the renowned Kenyan political science professor, Ali Mazuri, on why Africa should be socialist.[6]

A significant contribution by Rodney to the University's offerings was the introduction of a course entitled The History of Blacks in America. It enabled African students to connect their struggle against colonialism and neocolonialism with the Black struggle against racism in the US. His most famous work, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, which was first published in England in 1972, was written during this period.[10] He was one of the main speakers at the African Liberation Day Rally, 25 May 1972 in San Francisco. Some of his most important papers in this period were reproduced by the Institute of the Black World in Atlanta, Georgia.[2]

In the same period, he wrote critical articles on Tanzanian Ujamaa, imperialism, on underdevelopment, and the problems of state and class formation in Africa. Many of his articles which were written in Tanzania appeared in Maji Maji, the discussion journal of the TANU Youth League at the University. He worked in the Tanzanian archives on the question of forced labour, the policing of the countryside and the colonial economy. This work was later published as a monograph by Cornell University in 1976: World War II and the Tanzanian Economy. In Tanzania he developed close political relationships some of the leaders of liberation movements in Southern Africa and also to political leaders of popular organizations of independent territories. [2]

Together with other Pan-Africanists he participated in discussions leading up to the Sixth Pan-African Congress, held in Tanzania, 1974. Before the Congress he wrote a piece: 'Towards the Sixth Pan-African Congress: Aspects of the International Class Struggle in Africa, the Caribbean and America'. Walter Rodney withdrew his support of the Sixth Pan-African Congress over the controversy relating to the inclusion or exclusion of oppositional parties over or alongside representatives of the recently formed independent states, himself being placed resolutely into the faction who saw the Congress as a forum for oppositional groups and radical movements, i.e. nongovernmental in nature.[1]

However, despite finding himself in a fruitful intellectual climate, he writes:

"As long as I remained in Tanzania as a non-Tanzanian, as a marginal participant in the political culture, then it followed that I couldn't change my role. I would just have to remain at the university. I was in a fixed political role and my own feeling was that to break beyond those boundaries it was necessary to return once more to the Caribbean. That is the background that explains why I am in the Caribbean and in Guyana today ."[3]

Additionally, he and his wife wanted their children to experience Guyana.[1]

In 1974 he left Tanzania to return to Guyana to work as Professor of History at the University of Guyana. On his way home to Guyana, he lectured extensively in the United States and there helped to clarify some of the questions of class and race within the context of African and black American struggle.[2]

Guyana (1974-1980)[edit | edit source]

Throughout his years in Tanzania, Walter Rodney remained in close touch with developments in the Caribbean. He also, periodically, made visits to the United States and the UK where he gave guest lectures at several universities coupled with "groundings" in Caribbean emigrant communities, being widely read and respected in progressive sectors of the black community - being seen as offering a creative application of historical materialism to Africa.[11]

Eusi Kwayana (cofounder of the WPA) describes the mood ahead of Walter Rodney's return to Guyana as:

“[T]he whole country was looking forward to Dr. Walter Rodney, even before he set foot in Guyana. From the time he was banned from Jamaica and came to the notice of the public as a son abroad, he was a very popular figure in the imagination and hearts of the Guyanese people.”[1]

Rodney applied to the University of Guyana through the appropriate channels and was offered a professorship of history. He travelled back to Guyana in September 1974. The Forbes Burnham government blocked his appointment. Although the Government refused to allow him to teach, he decided to stay in the country in order to contribute his knowledge, experience and ideas to the Guyanese working people. Shortly after he had returned to Guyana he began to work among the workers. He was one of those who was instrumental in the foundation of a new political organization called the Working People's Alliance (WPA) in 1974[11]. Walter Rodney was an executive member of the Working People's Alliance and a full-time organizer of the party in Georgetown.[2]He helped organize Bauxite workers who were already starting their own organisations, such as the OWP (Organisation of the Working People), as well as educational work in political economy and the history of revolutions, giving classes to workers in their homes and even overnighting with their families and organising multi-week long session on sunday mornings.[12] The political context of the foundation of this Party is described by Chinedu Chukwudinma as follows:

"The racial conflict in Guyana produced a political system that only allowed space for Forbes Burnham’s People’s National Congress (PNC) and its opposition, Cheddi Jagan’s People’s Progressive Party (PPP). Both parties preached a version of socialism from above that favoured the petty bourgeoisie’s control over the state, never the masses. Burnham blatantly discriminated against the Indo-Guyanese, while Jagan talked about racial unity but, when it came to elections, only campaigned among Indians."[13]

Rodney's intellectual and political work was then focused primarily on the history of the Guyanese working class. He felt that such a history was needed to clarify the misconceptions which had been the basis of some of the racial divisions in the society. In the summer of 1977 he immersed himself in the records of the British Public Records office to unearth the details of the material divisions which formed the basis of the Indian-African divide in the society. This work is published as A History of the Guyanese Working Class. He had also compiled and edited a document called Guyanese Sugar Plantations in the late 19th Century. This work was part of his research into the plantation records in Guyana and in the United Kingdom.[2]

In 1978, Rodney went to Hamburg, Germany as a visiting professor. He was invited by Rainer Tetzlaff and Peter Lock, two radical lecturers at the University of Hamburg to teach the course, ‘One Hundred Years of Development in Africa’, between April and June. The lectures were recorded, and full transcripts were made in 1984, including the question and answer sessions with the students.[14]

In 1979 he was charged with arson after a fire destroyed the headquarters of the ruling People's National Congress in Guyana. Walter Rodney and four other persons were arreted in 13th September 1979 in Leonara, West Demerara "during a roadblock search for arms and ammunition", but released without a charge, his house being ransacked in the process. He was once again arrested in Linden "for the distribution of subversive literature",on October 3rd and tried from the 24th to the 26th of October.[12] After being held in prison for a short while, Walter Rodney and his three co-defendants were granted bail after widespread national and international protest at their being arrested.[2]

Two speeches given at mass rallies in Georgetown during this period by Rodney have been reproduced as pamphlets: The Struggle Goes On and People's Power, No Dictator. These speeches, along with a short piece in Transition, were to be his last major contribution to the discussion of the form of state which should emerge or could emerge in Guyana in opposition to Forbes Burnham.[2]

Rodney left Guyana illegally in February 1980, going to Europe (including Hamburg) and Africa and returning sometime in May. Rodney was invited to Zimbabwe to attend the Independence Celebrations on the 16th May 1980[12], which he was prevented form attending. He managed regardless, and was offered by Robert Mugabe to set up a research institute there - a offer Rodney declined.[2]

Walter Rodney was assasinated on the 13th June 1980, in a context of deepening repression against members of the WPA (39 WPA members were arrested in the period from 31st May to the 12th June 1980), by an ex-officer of the Guyana Defense Force, by car bomb.[12]

Assassination[edit | edit source]

On 13 June 1980, Rodney was killed in Georgetown, at the age of 38, by a bomb explosion in his car, a month after he returned from celebrations of independence in Zimbabwe at a time of intense political activism. He was survived by his wife, Patricia, and three children. His brother, Donald Rodney, who was injured in the explosion, said that a sergeant in the Guyana Defence Force named Gregory Smith, had given Walter the bomb that killed him. After the killing, Gregory Smith fled to French Guiana, where he died in 2002.[15]

In 2014, a Commission of Inquiry (COI) was held during which a new witness, Holland Gregory Yearwood, came forward claiming to be a long-standing friend of Rodney and a former member of the WPA. Yearwood testified that Rodney presented detonators to him weeks prior to the explosion asking for assistance in assembling a bomb. Yet the same Commission of Inquiry (COI) concluded in their report that Rodney's death was a state-ordered killing, and that then Prime Minister Forbes Burnham must have had knowledge of the plot.[16]

Donald Rodney was in the car with him during the time of the assassination, and was convicted in 1982 of possessing explosives in connection with the incident that killed his brother. On 14 April 2021, the Guyana Court of Appeals overturned this judgment and Donald's sentence, exonerating him after forty years in which he contested his conviction.[17]

Work and Thought[edit | edit source]

Groundings with my Brothers[edit | edit source]

Statement of the Jamaican Situation[edit | edit source]

Black Power, a Basic Understanding[edit | edit source]

Black Power- Its Relevane to the West Indies[edit | edit source]

African History and Culture[edit | edit source]

African History in the Service of Black Revolution[edit | edit source]

The Groundings with My Brothers[edit | edit source]

How Europe Underdeveloped Africa[edit | edit source]

Rodney on Class Relations, Class Formation and State Formation in Africa[edit | edit source]

Rodney on Tanzania[edit | edit source]

Rodney on African Leaders[edit | edit source]

Rodney describes african "petit bourgeois regimes" as progressive in the following sense, and situates many a african leader within this category, such as Nasser, Nkrumah, Nyerere and Sekou Toure:

"It would be unhistorical to deny the progressive character of the African petty bourgeoisie at a particular moment in time. Owing to the low level of development of the productive forces in colonized Africa, it fell to the lot of the small privileged educated group to give expression to a mass of grievances against racial discrimination, low wages, low prices for cash crops, colonial bureaucratic commandism, and the indignity of alien rule as such. But the petty bourgeoisie were reformers and not revolutionaries. Their class limitations were stamped upon the character of the independence which they negotiated with the colonial masters. In the very process of demanding constitutional independence, they reneged on the cardinal principle of Pan-Africanism: namely, the unity and indivisibility of the African continent."[18]

while specifically singling out Nkrumah, Nyerere and Sekou Toure etc. as follows, as being - albeit being components of the african petit bourgeoisie - somewhat more hesitant in accepting the continuation of imperialist economic relations:

"Imperialism defined the context in which constitutional power was to be handed over, so as to guard against the transfer of economic power or genuine political power. The African petty bourgeoisie accepted this, with only a small amount of dissent and disquiet being manifested by the progressive elements such as Nkrumah, Nyerere and Sekou Toure."[18]

Criticism of Nkrumah[edit | edit source]

Rodney situates Kwame Nkrumah in the category of "petit bourgeois regimes", which he describes - within an african context - as being progressive as above. He further accuses Nkrumah as being ideologically obscurantist in the following quote, while only regocnizing class struggle in africa post-overthrow:

"Nkrumah was engaging in ideological mystification under new facades such as 'consciencism', while doing little to break the control of the international bourgeoisie or the Ghanaian petty bourgeoisie over the state. He had already eliminated the genuine working class leadership from the CPP during the first years of power, and it was only after his overthrow by a reactionary petty bourgeois coup d'etat that Nkrumah became convinced that there was a class struggle in Africa and that the national and Pan-African movements required leadership loyal to its mass base of workers and peasants."[18]

He further elaborates this point in the speech entitled Marxism and African Liberation he gave at Queen's College. Firstly, he attacks Kwame Nkrumahs supposed Protestantism as entrapping him in bourgeois thought:

"Nkrumah followed up on this; and although at one, time he called himself a Marxist, he always was careful to qualify this by saying that he was also a Protestant. He believed in Protestantism, at the same time. So he was trying to straddle two worlds simultaneously - the world which says in the beginning was matter and the world which says in .the beginning there was the word. And inevitably he fell between these two. It's impossible to straddle these two. But there he was, and we must grant his honesty and we must grant the honesty of many, people who have attempted to do this impossible task and follow them to find out why they failed. They failed because their conception of what was a variant different from bourgeois thought and different from socialist thought inevitably turned out to be merely another branch of bourgeois thought."[19]

He then continues to criticize his supposed ideological syncretism as rendering him unable to understand socialism:

"Nkrumah spent a number of years during the fifties and, right up to when he was overthrown - that would cover at least ten years - in which he was searching for an ideology. He started out with this mixture of Marxism and Protestantism, he talked about pan-Africanism; he went to Consciencism and then Nkrumahism, and, there was everything other than a straight understanding of socialism."[19]

He attributes to this ideological syncretism Nkrumahs supposed denial of the existence of classes and a disavowal of a international socialist tradition and scientific socialism:

"What were the practical consequences of this attempt to dissociate himself from an international socialist tradition? We saw in Ghana that Nkrumah steadfastly refused to accept that there were classes, that there were class contradictions in Ghana, that these class contradictions were fundamental. For years Nkrumah went along with this mish-mash of philosophy which took some socialist premises but which he refused to pursue to their logical conclusion - that one either had a capitalist system based upon the private ownership of the means of production and the alienation of the product of people's labour, or one had an, alternative system which was completely different and that there was no way of juxtaposing and mixing these two to create anything that was new and viable."[19]

Additionally, he claims that Nkrumah changed his position upon being overthrown, an attributes him being overthrown to Nkrumahs unwillingness or inabillity to acknowledge classes and his supposed seperation from scientific socialism:

"A most significant test of this position was when Nkrumah himself was overthrown! After he was overthrown, he lived in Guinea-Konakry and before, he died he wrote a small text, Class Struggle in Africa. (...) It is historically important, because it is there Nkrumah himself in effect admits the consequences, the misleading consequences of an ideology which espoused an African cause,.but which felt, for reasons which he did not understand; an historical necessity to separate itself from Scientific Socialism. It indicated quite clearly the disastrous consequences of that position. Because Nkrumah denied the existence of classes in Ghana until the petty bourgeoisie as a class overthrew him. And then, in Guinea, he said it was a terrible mistake. "[19]

These critiques were tackled by e.g. Gorkel a Gamal Nkrumah in the text Rejoinder to Dr. Walter Rodney's Criticism of Dr. Kwame Nkrumah. In it, he asserts that these critiques are based on a misrepresentation of "celebrity academics". He reasserts that Nkrumaism represents the coalescence of pan-Africanism and scientific socialism, is a developing ideology, with "static cournerstones". These are: the total liberation of Africa and Africans, the political unification of Africa as a prelude to Africa's economic integration,and the commitment to scientifc socialism, which Kwame Nkrumah, according to Gorkel a Gamal Nkrumah, was instrumental in wedding to pan-Africanism as its earliest african theoretician. He attributes Rodneys accusations to "the paucity of evidence available to him", and as being "without foundation". He also elaborates on the basis of a overview of the Ghanaian Revolution and its sucesses that the claim that Kwame Nkrumah was ideological inconsistent, as him "wandering in an ideological wilderness", is false, instead asserting that Nkrumah laid the "foundation for economic and social reconstruction based on the principles of scientific socialism".[20]

Rodney on Pan-Africanism[edit | edit source]

Rodney on the Russian Revolution and the Soviet Union[edit | edit source]

Walter Rodney's book, The Russian Revolution: A View from the Third World describes many liberal criticisms of the Soviet Union as idealist or un-materialist.[5]

Bibliography[edit | edit source]

On African History[edit | edit source]

- A History of the Upper Guinea Coast 1545-1800 (1970)

- How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (1972)

- West Africa and the Atlantic Slave Trade (1967)

- "European Activity and African Reaction in Angola" Aspects of Central African History (1968)

- "The Guinea Coast" The Cambridge History of Africa 1600-1790 Vol.4 (1975)

- "African Slavery in the Context of the Atlantic Slave Trade" The Black Americans: Interpretive Readings (1971)

- "Gold and Slaves on the Gold Coast" Transactions of the Ghana Historical Society, Vol.X (1969)

- "Upper Guinea and the Significance of the Origins of Africans Enslaved in the New World" Journal of Negro History, No.4 (1969)

- "Recruitment of Askari in Colonial Tanganyika" East African University Social Science Conference Papers (1973)

- "African Slavery and Other Forms of Social Oppression on the Upper Guinea Coast in the Context of the Atlantic Slave Trade" Perspectives of the African Past, also in Journal of African History, VII, 3 (1966)

- "Portuguese Attempts At Monopoly On the Upper Guinea Coast, 1580-1850" Journal of African History, VI, 3 (1965)

- "A Reconsideration of the Mane Invasion of Sierra Leone" Journal of African History, VIII, 2 (1967)

- "West Africa and the Atlantic Slave Trade" Historical Association of Tanzania, Paper No.2 (1967)

- "Jihad and Social revolution in Futa Djalon in the Eighteenth Century" The Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria Vol.4, No.2 (1968)

- "The Year 1985 in Southern Mozambique African Resistance to the Imposition of European Colonial Rule" The Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria, Vol.V, No.4, (1971)

- "The Colonial Economy" General History of Africa VII: Africa under Colonial Domination 1880-1935, Editor: A. Boahen

On Imperialism[edit | edit source]

- "The Imperialist Partition of Africa" Monthly Review, Special Edition 'Lenin Today', Vol.21, 1970.

On the Neo-Colonial Period- The State- Tanzania[edit | edit source]

- "Education in Africa and Contemporary Tanzania" Education and Black Struggle: Notes from the Colonized World, Harvard Educational Review, No.2 (1974)

- "Tanzania Ujamaa and Scientific Socialism", African Review, Vol.2, No.1 (1972)

- "African History and Development Planning", Movement (1974)

- "State Formation and Class Formation in Tanzania" Maji Maji, (Dar es Salaam) (1973)

- World War 2 and the Tanzanian Economy,Cornell University, Africana Studies and Research Centre, Ithaca (1976)

- "Politics of the African Ruling Class", transcription of a lecture given in USA, 1974.

- "Notes on Disengagement from Imperialism", East African University Social Science Conference, 1970.

- "Class Contradictions in Tanzania" The State in Tanzania (1980)

- "Education and Tanzanian Socialism" Revolution by Resolution (1968)

On Socialist Transformations[edit | edit source]

- 'Declaration: Implementation Problems', Mbioni, Journal of Kivukoni College, Dar es Salaam, August 1967

- . 'Guyana's Socialism: An Interview with Walter Rodney', Colin Prescod, Race and Class, XVIII, No.2, 1976.

- 'Transition', Transition, Vol.1, No.1, (Guyana), 1978.

- The Struggle Goes On, A WPA Publication, Georgetown, Guyana, August 1979, reprinted by WPA Support Group (UK), London, June 1980.

- People's Power, No Dictator, A WPA Publication, (Georgetown, Guyana, 1979).

- 'Will The World Listen Now?' an interview with Walter Rodney in Guyana Forum, Vol.1, No.3, June 1980.

On Politics in the Carribean and Caribbean and Guyanese History[edit | edit source]

- Some Thoughts on the Colonial Economy of the Caribbean, delivered at the Carribean Unity Conference, Howard University, Washington DC, April 21, 1972,

- A New Beginning Pamphlet. Guyanese Sugar Plantations in the Late 19th Century - A Contemporary Description from the Argosy, edited and introduced by Walter Rodney, (Release Publishers, 258 Forshaw Street, Georgetown, Guyana 1979).

- A History of the Guyanese Working Class, (John Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1980). 'Contemporary Trends in the English-Speaking Caribbean', Black Scholar, Vol.7, No. 1, 1975.

- 'The Colonial Economy: Observations on British Guiana and Tanganyika', Institute of Commonwealth Studies Seminar Papers, 1977.

- 'Immigrants and Racial Attitudes in Guyanese History', Institute of Commonwealth Studies Seminar Papers, 1977.

- 'Internal and External Constraints on the Development of Guyanese Working Class', Georgetown Review, Vol.1, No.1, August 1978.

On Pan-Africanism[edit | edit source]

- 'Towards the Sixth Pan-African Congress, Aspects of the International Class Struggle in Africa, the Caribbean and America, 1975

On Rastefarianism[edit | edit source]

- The Groundings With My Brothers

Newly Published[edit | edit source]

- The Russian Revolution: A View from the Third World

- Decolonial Marxism: Essays from the Pan-African Revolution

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Leo Zeilig (2022). A Revolutionary for our Time: The Walter Rodney Story. Chigaco: Haymarket Books. [LG]

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 Horace Campbell (1980). Walter Rodney; A Biogaphy and Bibliography (pp. 132-137). Review of African Political Economy, No. 18, Special Issue on Zimbabwe. doi: 10.2307/3997943 [HUB]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Edited by Robert A. Hill (1990). Walter Rodney Speaks: The Making of an African Intellectual: 'Part I (Walter Rodney)' (pp. 17-53). Trenton: Africa World Press, Inc.. [LG]

- ↑ Katie Price (2015-09-23). "Revolutionary historian: Walter Rodney (1942-1980)" SOAS University of London, Centary Timeline. Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Curry Malott, Elgin Bailey (2022-08-01). "Walter Rodney: A people’s professor" Liberation School. Retrieved 2022-08-05.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Chinedu Chukwudinma (2022-04-07). "The Mecca of African Liberation: Walter Rodney in Tanzania" Review of African Political Economy (ROAPE). Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Michael O. West (2005). Walter Rodney and Black Power: Jamaican Intelligence and US Diplomacy. [PDF] African Journal of Criminology & Justice Studies: AJCJS; Volume 1, No.2.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Walter Rodney (1969). The Groundings with my Brothers (pp. 60-66). London: Bogle- L'Ouverture Publications. [LG]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Vijay Prashad (2023-06-15). "Walter Rodney and the Russian Revolution" Verso. Retrieved 2023-07-08.

- ↑ Viola Mattavous Bly (1985). Walter Rodney and Africa (p. 119). Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 16, No. 2. doi: 10.2307/2784257 [HUB]

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Trevor A. Campbell (1981). The Making of an Organic Intellectual: Walter Rodney (1942-1980) (pp. 49-63). Latin American Perspectives, Vol. 8, No. 1, The Caribbean and Africa. doi: 10.2307/2633130 [HUB]

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Rupert Charles Lewis (1998). Walter Rodney's Intellectual and Political Thought (pp. 238-241). Barbados Press University of the West Indies and Wayne State University Press. [LG]

- ↑ Chinedu Chukwudinma (2022-03-12). "The birth of the Working People’s Alliance in Guyana" Review of African Political Economy (ROAPE). Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ↑ Leo Zeilig (2019-02-14). "Walter Rodney’s Journey to Hamburg" Review of African Political Economy (ROAPE). Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ↑ Abayomi Azikiwe (2016-02-28). "Guyana commission confirms Burnham gov’t murdered Walter Rodney" Mundo Obrero Workers World. Archived from the original. Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ↑ Walter Rodney Commission of Inquiry, (2016). Report of the Commission of Inquiry Appointed to Enquire and Report on the Circumstances Surrounding the Death of the Late Dr. Walter Rodney on Thirteenth Day of June, One Thousand Nine Hundred and Eighty at Georgetown. Walter Rodney Commission of Inquiry.

- ↑ Denis Chabrol (2021-04-13). "BREAKING: Guyana Court of Appeal sets aside explosives conviction, sentence of Donald Rodney" DemeraraWaves. Retrieved 2023-07-09.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Walter Rodney (1975). Aspects of the International Class Struggle in Africa, the Caribbean and America (pp. 18-41). in Pan-Africanism: Struggle against Neo-colonialism and Imperialism - Documents of the Sixth Pan-African Congress, Horace Campbell, Toronto: Afro-Carib Publications. [MIA]

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Walter Rodney (1975). Marxism and African Liberation. [PDF] Speech by Walter Rodney At Queen's College, New York in Yes to Marxism!, People's Progressive Party. [MIA]

- ↑ Gorkeh A Gamal Nkrumah (1989). Rejoinder to Dr. Walter Rodney's criticism of Dr. Kwame Nkrumah (pp. 51-54). [PDF] Frank Talk Volume 3.