More languages

More actions

| Republic of Ireland Poblacht na hÉireann | |

|---|---|

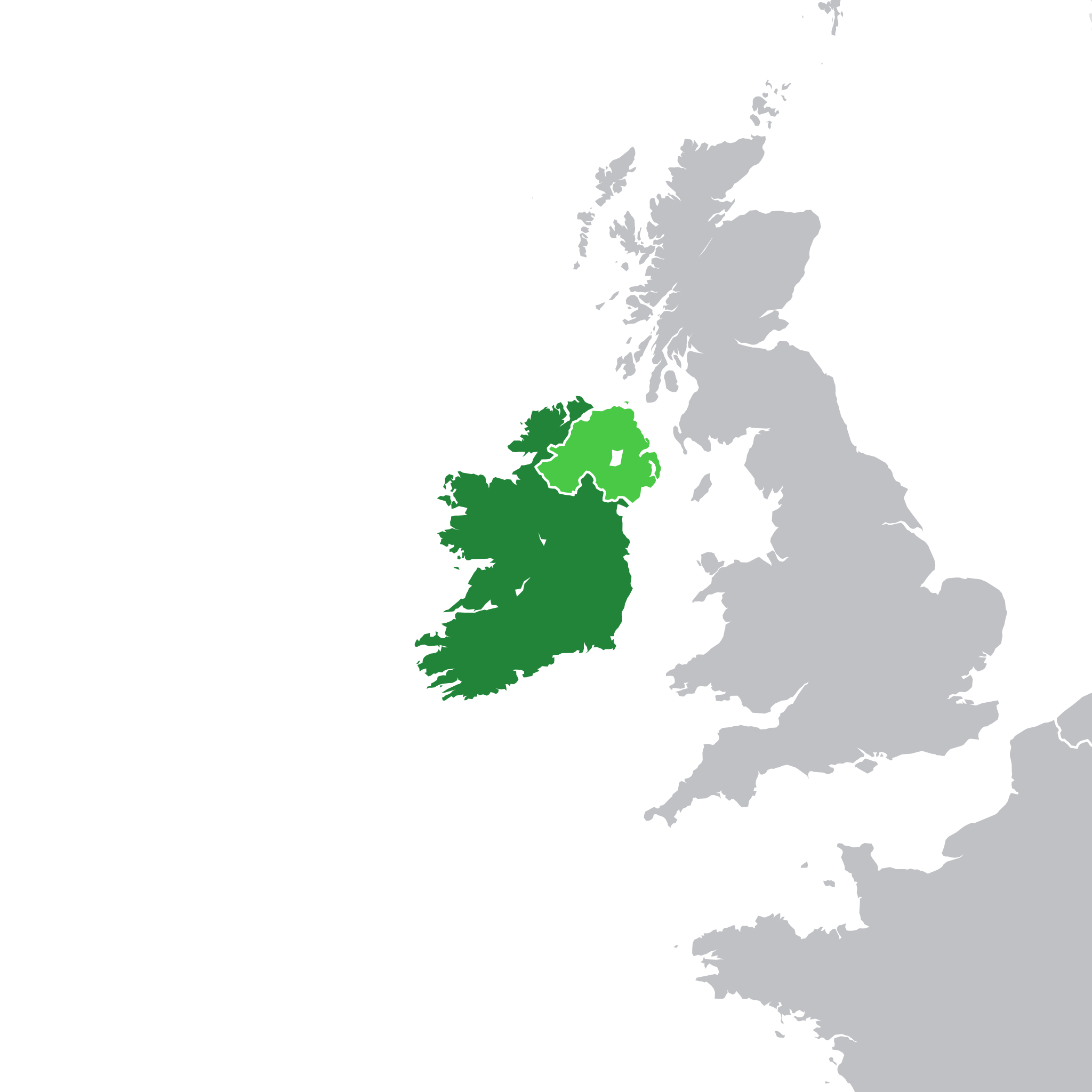

Light green area is under British occupation. | |

| Capital and largest city | Dublin |

| Official languages | English, Irish |

| Dominant mode of production | Capitalism |

| Government | Parliamentary republic |

• President | Michael D. Higgins |

• Taoiseach | Simon Harris |

| Area | |

• Total | 70,273 km² 84,421 km² (including occupied counties) |

| Population | |

• 2021 estimate | 5,011,500 |

| Labour | |

• Unemployment rate | 26% |

The Republic of Ireland is a country in Europe. Formerly a British colony, six of its 32 counties are still occupied by the United Kingdom.[1] Since the island was partitioned in 1921, Irish Republicans have been fighting for unification. On 5 May 2022, Sinn Féin, formerly the political arm of the Irish Republican Army, won the Northern Ireland Assembly election, igniting hope of unification in the near future.[2]

History[edit | edit source]

Early British settlement[edit | edit source]

In the early 17th century, England opened 500,000 acres in the north of Ireland to settlers from Scotland. The English banned traditional Irish music and culture and exterminated entire clans. They tried to create a reservation for the Irish. The English paid bounties for Irish heads and later only required scalps or ears.[3]

In 1654, Oliver Cromwell conquered Ireland and ended Celtic control of the country's land.[4] In 1725, the British passed a law banning marriages between the Irish and English.[5]

French Revolutionary wars[edit | edit source]

Theobold Wolfe Tone, a radical Protestant, founded the United Irishmen to fight for Irish independence. They began an uprising in 1798 that united Protestants and Catholics against British rule. The British killed 30,000 rebels, and French troops failed to arrive on time to support the resistance.[6]

Following the rising, in 1800 the Irish parliament, mostly controlled by the English, voted itself out of existence and in 1801, the Act of Union allowed Great Britain to officially annex Ireland.[7]

British occupation (1801–1922)[edit | edit source]

The Insurrection Act in Castlebar allowed the British to deport any man found outside at night without a passport.[5]

During the 1913 Dublin lockout, English workers raised money for the Irish, but the bureaucracy of the Trades Union Congress refused to support the strike.[8]

Great Famine[edit | edit source]

In 1845, the British appointed Charles Trevelyan to administer Ireland during a famine. Trevelyan adopted a laissez-faire attitude and wrote that the famine was an "effective mechanism for reducing surplus population" and "the judgement of God to teach the Irish a lesson." Exports of food from Ireland increased during the famine and over a million people starved to death.[9] The population of Ireland had been nearing nine million when the potato blight struck. By the time the Famine officially ended in 1852, it had fallen to six, and it would continue to decline steeply in the following decades, a population decrease that Ireland still has not recovered from in the modern day.[7]

Easter Rising[edit | edit source]

See main article: Easter Rising

In 1914 the First World War began in Europe, and although preparations for an Irish revolt had already begun, the distraction of the war for the British provided the Irish with an opportunity. Emissaries were sent to Berlin to secure weapons and other practical assistance from the German government, but in the end they came away with much less than they had hoped for and on the return journey to Ireland the supplies were captured.[7]

On 24 April 1916, Pádraic Piarais read out an Irish proclamation of independence, beginning a proletarian rebellion against the British that lasted for six days.[10] The rising was to be a failure before it even began but the Irish still fought valiantly for their freedom, with roughly 1,500 rebels taking up arms in Dublin before they were brutally crushed by the British. After the Easter Rising ended, the British executed all seven signers of the proclamation including Piarais himself, James Connolly and Thomas Clarke, and along with several other leaders.[7]

War of Independence[edit | edit source]

The Dáil Éireann, Ireland's legislature, met for the first time during the Irish War of Independence and read out the Declaration of Independence and the Message to the Free Nations of the World.[11] A treaty signed in December 1921 in London ended the Civil War but retained the British king as head of state and allowed Britain to retain colonial control of the northeastern six counties. The Dáil approved the treaty in January 1922 with a vote of 64 to 57.[12]

Opponents of the treaty founded Fianna Fáil while supporters founded the predecessor of Fine Gael. An anti-treaty faction of Sinn Féin refused to accept the treaty, and a civil war began.[12]

Politics[edit | edit source]

Since its partial independence from Britain, a duopoly of Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael has dominated Ireland. Both parties support low taxes and allow international imperialists to exploit the country. The center-left Green Party also supports austerity and bailing out banks.

Sinn Féin seeks to improve living standards, reunify Ireland, and end collaboration with the European Union and NATO.[12]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Brendan O'Brien (1999). The Long War: The IRA and Sinn Féin (p. 167). Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815605973

- ↑ Steve James (2022-05-08). "Sinn Féin wins Northern Ireland Assembly election" World Socialist Web Site.

- ↑ Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (2014). An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States: 'Culture of Conquest' (p. 38). ReVisioning American History. [PDF] Boston: Beacon Press Books.

- ↑ James Connolly (1915). The Re-Conquest of Ireland: 'The Conquest of Ireland'. [MIA]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Domenico Losurdo (2011). Liberalism: A Counter-History: 'Were Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century England and America Liberal?' (p. 116). [PDF] Verso. ISBN 9781844676934 [LG]

- ↑ Neil Faulkner (2013). A Marxist History of the World: From Neanderthals to Neoliberals: 'The Second Wave of Bourgeois Revolutions' (p. 130). [PDF] Pluto Press. ISBN 9781849648639 [LG]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Tim Pat Coogan (2016). 1916: one hundred years of Irish independence: from the Easter Rising to the present: 'The Road to the Rising' (pp. 7-38). ISBN 9781250110602

- ↑ Vijay Prashad (2017). Red Star over the Third World: 'Follow the Path of the Russians!' (p. 35). [PDF] New Delhi: LeftWord Books.

- ↑ Larry Holzwarth (2018-03-17). "10 Atrocities Committed by the British Empire that They Would Like to Erase from History Books" History Collection. Archived from the original on 2021-06-16. Retrieved 2022-05-21.

- ↑ "The 1916 Easter Rising remembered" (2016-04-01). Proletarian. Archived from the original on 2022-05-16. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ↑ Michael Hopkinson. The Irish War of Independence: The Definitive Account of the Anglo Irish War of 1919–1921 (pp. 85–87). Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 9780717161980

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Ella Rule (2020-07-30). "Ireland gets the government it didn’t vote for" Proletarian. Archived from the original on 2022-05-17. Retrieved 2022-12-04.