More languages

More actions

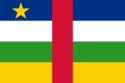

| Central African Republic Ködörösêse tî Bêafrîka République centrafricaine | |

|---|---|

| |

| Capital and largest city | Bangui |

| Dominant mode of production | Dependent Capitalism |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

• President | Faustin-Archange Touadéra |

• Prime Minister | Félix Moloua |

| Area | |

• Total | 622,984 km² |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 5,552,228 |

The Central African Republic (CAR) is a landlocked country in Africa bordered by Chad, Sudan, South Sudan, DRC, Republic of the Congo, and Cameroon.

History[edit | edit source]

Precolonization[edit | edit source]

The Sao Civlization[edit | edit source]

The Sao Civilization was a network of complex societies in Central Africa. It emerged around the southern margin of the Lake Chad Basin between 600–500 BCE. They are best known for their distinctive terracotta sculptures, metalworking, and walled, fortified cities, as well as a myth describing them as a race of giants. It could be considered a loose confederation of multiple independent city-states.[1]

The Sao economy was mainly a mix of fishing, agriculture, and metallurgy. The wetlands and floodplains of Lake Chad supported populous settlements and a surplus of produce, which enabled specialized artisans such as ironworkers and terracotta sculptors. Archaeologically, we see fortified towns, cemeteries rich in jewelry, and workshops indicating social stratification. These elite burials, luxury goods, and fortified architecture convey a ruling class that controlled the surplus and labor. The Sao ruling class oversaw the trade routes and the workshops.[1]

Artistically, the Sao left a rich material culture, with thousands of terracotta figurines representing humans and animals. These typically featured elaborate hairstyles and jewelry. They also produced bronze and iron ornaments, ritual paraphernalia, and jewelry. The Sao expressed social hierarchies and ancestral faith through their art.[1]

The Sao were surrounded by powerful neighbors such as the Hausa and the Fulani around Lake Chad, and trade between these states increased the demand for metals and cloth. The decline of the Sao had multiple causes, including ecological changes in Lake Chad, competition with emerging neighboring states for resources, and invasion. The Kanem-Bornu Empire expanded from the northeast, attempting to claim the Sao as their territory. The Sao resisted for centuries but were ultimately absorbed in the 16th century.[2]

The Kanem-Bornu Empire[edit | edit source]

Kanem-Bornu began as Kanem on the northeastern shores of Lake Chad. It was the longest-lasting state in Africa and the fourth longest-lasting continuous state in the world, spanning over 1,200 years of continuous rule, roughly from the 8th century CE to the 19th century CE. It dominated the Sahel region around Lake Chad, controlling the trans-Saharan trade routes while serving as a center of Islamic scholarship.[3]

It emerged in the 8th century on the shores of Lake Chad as the Duguwu royal dynasty. It was originally formed by Zaghawa nomads, but as social stratification intensified, a group of aristocrats known as the Duguwu came to rule. It originally grew as an agrarian and pastoralist society in the oases and floodplains of Lake Chad, with the aristocratic Duguwu controlling the oases, caravan routes, and grazing areas. The Duguwu accumulated surplus through their control of pastures, water, and access to trade.[3]

The charter myth proposes that the legendary founder was Sayf, a divine king who was a semi-divine being said to speak to spirits. They created a sense of mystique by never being seen eating and by being rarely seen in public. Spirits were central to this charter myth, as Kanem was animist and based on a concept called mune, a sacred talisman that guaranteed the safety of the state. Naturally, these myths served as justifications by the Duguwu nobility for their class dominance and therefore had to connect their rule with the population’s animist beliefs.[3]

Islam reached Kanem by the 8th century; the religion was introduced from the north by Toubou merchants. It is assumed that Islam had replaced animism by the 9th century, specifically with Ibadi Islam. The Duguwu nobility were initially hesitant about Islam, as they feared that the concept of equality among all believers before God threatened their class rule. The first Muslim ruler is assumed to have been Hawwa, a woman, though the gender is contested.[3]

As Islam continued to spread within Kanem, the Duguwu nobility were overthrown by the Sayfawa dynasty. Literacy spread through Islamization, and in the 10th and 11th centuries, raiding across the central Sahara became the means by which Kanem began to grow and expand. This Islamization created diplomatic and commercial relations with states in North Africa. Islamic scholarship became interwoven with the existing African political structure, with Arabic chancery records and madrasas.[3]

Around the 13th century, the Kingdom of Kanem transitioned into the Kanem-Bornu Empire when it was forced to flee to Bornu due to a breakaway faction of the nobility known as the Bulala, who practiced a less orthodox form of Islam and established their own sultanate called the Sultanate of Yao. Over the next century, Bornu absorbed the local population and rebuilt, reaching the peak of its power in the 16th century. It received firearms from the Ottoman Empire and employed Ottoman military advisors. With this assistance, it was able to reconquer Kanem from the Bulala and absorb the Sao civilization.[4]

The Kanem-Bornu Empire served as a central hub of trans-Saharan trade, with caravans entering and leaving with salt, cloth, horses, and slaves, producing a surplus that the ruling class appropriated. Slave trading and capture were integral to this Saharan route, enriching the bourgeoisie with luxury goods from the Ottoman Empire and Europe.[3]

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, Kanem-Bornu experienced a multi-causal crisis. The Lake Chad Basin suffered four to five major drought cycles, which were devastating. At the same time, the intensification of the slave trade led to internal revolts, as the ruling class relied heavily on it for their wealth. The final blow came when the Fulani Islamic scholar Usman dan Fodio declared a jihad across the Sahel, creating the Sokoto Caliphate and sacking Bornu, leaving the Sayfawa unable to defend themselves.[5]

Though the empire was saved by the Islamic scholar and warrior Muhammad al-Kanemi and his followers, al-Kanemi, an influential sheikh within Bornu, resisted the Fulani jihad both militarily and through correspondence. The Fulani jihad aimed to remove pagans from the Sahel, but al-Kanemi challenged this rhetoric, arguing that it was not Islamically aligned and highlighting that the Kanem-Bornu Empire had been a Muslim state for 800 years, thereby exposing the Fulani’s expansionist intentions behind their ideological claims.[5]

Through his letters and his success in repelling the Fulani forces, Muhammad al-Kanemi became a revered figure. The Fulani threat eventually forced the Sayfawa dynasty to flee, and al-Kanemi was installed as the new ruler, taking the title of Shehu (scholar). This ended the 1,000-year Sayfawa dynasty in 1846 and established the Shehu dynasty. Forty-seven years later, in 1893, the Sudanese warlord Rabih az-Zubayr bin Fadlallah invaded with his army, sacking the capital and ruling for seven years. Subsequently, the French waged a seven-year campaign against Rabih, ultimately colonizing the Kanem-Bornu Empire. The territory of the former empire was then partitioned between the British, French, and Germans.[5]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Carlos Magnavita, James Ameje, Peter Breunig, Martin Posselt (2008). Zilum: A Mid‑First Millennium BC Fortified Settlement Near Lake Chad.

- ↑ Universität Hamburg. Conflict, Climate Change and Migration in the Lake Chad Basin.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Vincent Hiribarren (2016). Kanem‑Bornu Empire.

- ↑ Hiskett M. (1984). The Sword of Truth ; the life and times of the Shehu Usuman dan Fodio.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 R. A. Adelẹyẹ. Power and diplomacy in Northern Nigeria, 1804–1906: the Sokoto caliphate and its enemies,.