More languages

More actions

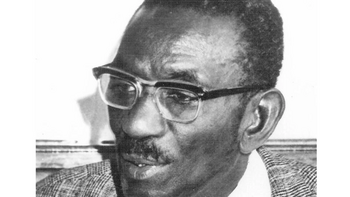

Cheikh Anta Diop | |

|---|---|

Cheikh Anta Diop | |

| Born | December 29, 1923 Diourbel Region,Senegal |

| Died | February 7, 1986 Dakar, Senegal |

| Cause of death | Heart Attack |

| Nationality | Senegal |

| Known for | The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality, Civilization or Barbarism: an authentic anthropology, Black Africa: the economic and cultural basis for a federated state , Precolonial Black Africa, The Cultural Unity of Black Africa: The Domains of Patriarchy and of Matriarchy in Classical Antiquity |

| Field of study | History, Anthropology, Egytptology, Archeology |

Cheikh Anta Diop (29 December 1923 – 7 February 1986) was a Senegalese historian, anthropologist, Egyptologist, archeologist, physicist, philosopher and pan-african political leader. [1]

Diop's work is considered foundational to Afrocentric Historiography and Afrocentricity more broadly[2]. The questions he posed about cultural bias in scientific research and colonial historiography contributed greatly to the "postcolonial" turn in the study of the history and structures of African civilizations away from the European and colonial conceptions, mostly through his studies of Ancient Egypt. This is sometimes referred to as Diopian Historiography.[3] Anta Cheikh Diop emerged in the twentieth century as a cultural nationalist whose contribution to ideological debate helped to galvanize the struggle for independence in Africa. Diop’s classical work on African cultural history, as well as his exposition of ancient Egyptian civilization as purely African, has earned him an esteemed, albeit often controversial, reputation in African and international scholarship. Cheikh Anta Diop advanced multiple theories, including the Two Cradle Theory[4], African Matriarchy, and Egypt as a black civilization[3].

Cheikh Anta Diop University (formerly known as the University of Dakar), in Dakar, Senegal, is named after him.[5] The African Renaissance movement was founded in the early 1990s by Théophile Obenga and Cheikh M'Backe Diop to expand upon the ideas of Cheikh Anta Diop. The Cheikh Anta Diop International Conference was initiated by Molefi Kete Asante to coincide with the introduction of the first doctoral program in African American Studies at Temple University, first held in October 1988.[3]

Biography[edit | edit source]

Early Life[edit | edit source]

Diop was born the son of Massamba Sassoum Diop and his wife Magatte Diop in the village of Caytou, near Bambey in the region of Diourbel, in west-central Senegal, then a French colony, in December 1923.[6] His family belonged to the Mouride brotherhood, a large tariqa (Sufi order) prominent in Senegal and Gambia.[1]

His first foray into formal scholarship was his 1940 translation of parts of Albert Einstein's work on special relativity into wolof.[7] He was educated locally, receiving both Koranic and Western education, then secondary education at Dakar and St Louis.[6]He obtained the colonial equivalent of the metropolitan French baccalauréat (Bachelors degree) in Senegal before moving to Paris to study for a degree.[8]

Studies in Paris, Early Political Conciousness and Scholarship[edit | edit source]

In 1946, at the age of 23, Diop went to Paris to study, and enrolled at the Sorbonne. He first enrolled into Advanced Mathematics, with the intention of becoming an aeronautic engineer, but then enrolled into the Faculty of Letters in Sorbonne for philosophy, under the tutelage of Gaston Bachelard. Parallel to his studies, he started his lingusitic investigation of wolof and serer, and entered into correspondence with Henri Lhote, a French explorer. He graduated with a degree in philosophy (licence de philosophie) in 1948, and enrolled into the Faculty of Sciences. In 1948, he published his first lingustic study in Présence Africaine, entitled Étude linguistique ouolove – Origine de la langue et de la race valaf. He also publishes in the same year in the journal Le Musée Vivant an article entitled Quand pourra-t-on parler d'une renaissance africaine? (When will we be able to speak of an African renaissance?), partly devoted to the question of the use and development of African languages, and in which Cheikh Anta Diop proposes for the first time to build the "African humanities" from the basis of a study of ancient Egypt, in the same vein as European culture is constructed on a Greco-Roman basis.

In 1949, Diop registered a proposed title for a Doctor of Letters thesis, "The Cultural Future of African thought" (L'avenir culturel de la pensée africaine), under the direction of Professor Gaston Bachelard. In 1950, he obtains certificates in for general and applied chemistry (chimie générale et chimie appliquée). He registers his second thesis entitled Qu'étaient les Égyptiens prédynastiques (What are the predynastic Egyptians) under the supervision of Marcel Griaule in 1951.

In 1953 Diop married his French wife Louise Marie Maes, the mother of his four children.[6]

Although he completed the thesis for his second title based on Ancient History and Egyptology in 1954, Diop had a problem finding a body of examiners to pass his work, and it was ultimately rejected by the acadmic authorites in France. Despite this,in 1955, he published his two thesis in book form via Éditions Présence Africaine, under the title: Nations nègres et Culture — De l'antiquité nègre égyptienne aux problèmes culturels de l'Afrique noire d'aujourd'hui (Negro Nations and Culture — From Egyptian Negro Antiquity to the Cultural Problems of Black Africa Today). In English this is published as part of the African Origin of Civilisation: Myth or Reality in 1974. [6]

From 1956 to 1957, he taught physics and chemistry at the Voltaire and Claude Bernard high schools in Paris as an assistant teacher.[6]

He re-registered two new theses titles:Les domaines du matriarcat et du patriarcat dans l'antiquité (The Areas of Matriarchy and Patriarchy in Ancient Times), in 1956, and Étude comparée des systèmes politiques et sociaux de l'Europe et de l'Afrique, de l'Antiquité à la formation des États modernes (Comparative Study of Political and Social Systems of Europe and Africa, from Antiquity to the Formation of Modern States) in 1957. In 1957, he debated French Egyptologist Jean Sainte-Fare Garnot.

He undertook a specialization in nuclear physics at the Nuclear Chemistry Laboratory of the Collège de France directed by Frédéric Joliot-Curie then at the Pierre and Marie Curie Institute, in Paris, in 1957. Cheikh Anta Diop had a special admiration for the French physicist, with whom he first came into contact in 1953.

From 1946 on, Anta Diop became actively involved in the growing African students anticolonial and Pan-African movements for independence in Paris. He co-founded the l'Association des Étudiants Africains de Paris in 1946, an organisation later headed by Amadou Mahtar M'Bow. He was a founding member, and later secretary general (1950–1953) of the student wing of the Rassemblement Democratique Africain, the first French-speaking Pan-African political movement launched in 1946 at the Bamako Congress to agitate for independence from France.[8] In July 1951 he helped to organise the first post-war Pan-African student congress in Paris, which included the participation of the London-based West African Students’ Union. From 1952–1954 Diop was also the political editor, as well as a major contributor, to AERDA’s monthly publication La Voix de L’Afrique Noire.[6]

In this position, he published several texts in the monthly newsletter of the organisation (The Voice of Black Africa, La Voix de l'Afrique noire), including Vers une idéologie politique africaine (Towards an African Political Ideology) in 1952 and La lutte en Afrique noire (The Struggle in Black Africa) in 1953.

And in 1956 and 1959, he participated in the First and Second World Congresses of Black Writers and Artists, in Paris and Rome, respectively.[8]

On January 9, 1960, he defended his doctoral thesis at the Sorbonne. It is published by Éditions Présence Africaine under the titles: Precolonial Black Africa and Black African Cultural Unity (L'Afrique noire précoloniale et L'Unité culturelle de l'Afrique noire). The historian André Leroi-Gourhan was his thesis director, and his jury was chaired by Professor André Aymard, then dean of the Faculty of Letters. A report on the defense of this thesis, which lasted several hours, was produced by the journalist Doudou Cissé and broadcast on Radiodiffusion d'Outre-Mer. In 1960 the Sorbonne finally awarded him a doctoral degree for research work that was subsequently published in English as Pre-colonial Black Africa (1987) and The Cultural Unity of Black Africa (1963).[6]

According to Diop's own account, his education in Paris included History, Egyptology, Physics, Linguistics, Anthropology, Economics, and Sociology.

His early influences are, according to Diop: Aime Cesaire, Democritus, Epicurus, Lucretius, Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, Georgi Phlekanov, Hegel, Goethe, Alfred de Vigny, Fustel de Coulanges and Albert Einstein.[9]

Later Life[edit | edit source]

In 1961, Anta Diop was appointed a research fellow at the Institut Fondamental d’ Afrique Noire (IFAN) where he later set up a radiocarbon dating laboratory. At IFAN, he continued establishing his theory of ancient Egypt being the precursor of modern civilization. By 1980, Diop had become famous for his free-carbon-dating work for African scholars from whom he received archaeological specimens for identification and analysis.[8]

By 1966 Diop, along with W.E.B Du Bois, was already being honoured by the First World Black Festival of Arts and Culture ‘as the writer who had exerted the greatest influence on African people in the twentieth century’. He also continued his involvement in politics and played a leading role in several political organisations including the Front National du Sénégal, and in 1962 was briefly imprisoned for his activities. In 1961 he was one of the founders and the first secretary-general of the Bloc des Masses Sénégalaises (BMS) which opposed the neo-colonial policies of the government of Leopold Senghor. In 1963 Diop and the BMS refused to accept ministerial posts in Senghor’s government, a stand that later that year contributed to the banning of the BMS by the Senegalese government.[6]

In 1979 Diop was charged with breaking the law for his involvement with the Rassemblement National Démocratique (RND), a new opposition organisation formed in 1976, but subsequently banned and denied legal recognition until 1981. In 1982 the RND won a seat in the National Assembly but Diop declined to enter parliamentary politics. Diop and the RND established a political journal written in Wolof entitled Taxaw (eng: Stand Up) as a vehicle for their criticism of the Senegalese government. In particular the journal voiced criticism of the government’s policy of retaining French as the medium of instruction in educational institutions.[6]

In 1970 Diop was invited to become a member of the UNESCO’s international committee established to oversee the writing and publication of the eight-volume General History of Africa. In 1974 he took part in the international symposium held in Cairo on the theme of ‘the peopling of Ancient Egypt’.

Belatedly, his historical work was given institutional recognition when he was appointed Professor of Egyptology and Prehistory at the University of Dakar in 1981.[9]

In his later works, such as Civilisation or Barbarism: An Authentic Anthropology, Diop continued to grapple with some of the key questions about Africa’s historical past, such as the existence of laws governing evolution and social change in African societies, the characteristics of African states and social structures and the controversy surrounding a peculiarly African mode of production.

In 1984, Black Africa: The Economic and Cultural Basis of a Federal State, is published, in which he outlines his ideas of political and economic pan-africanism.

Cheikh Anta Diop died of a heart attack on the 7th February 1986 in Dakar.[6]

Politics[edit | edit source]

Work and Thought[edit | edit source]

Influence, Reception and Critique[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Anna Micklin (2008-06-14). "Cheikh Anta Diop (1923-1986)" BlackPast.org. Retrieved 2023-08-07.

- ↑ Ana Monteiro-Ferreira (2014). The Demise of the Inhuman: Afrocentricity, Modernism and Postmodernism (p. 6). Albany: State University of New York Press. [LG]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Molefi Kete Asante and Ama Mazama (2005). Encyclopedia of Black Studies. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [LG]

- ↑ Troy D. Allen (2008). Cheikh Anta Diop's Two Cradle Theory: Revisited (pp. 813-829). Journal of Black Studies, Volume 38, Nr.6. doi: 10.2307/40035025 [HUB]

- ↑ Malenn-Kegni Toure (2009-02-08). "Cheikh Anta Diiop University (1957–)" blackpast.org. Retrieved 2023-08-07.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 Hakim Adi & Marika Sherwood (2003). Pan-African History: Political Figures from Africa and the Diaspora since 1787: 'Cheikh Anta Diop (1923-1986)' (pp. 40-42). London: Routledge (Taylor & Francis). [LG]

- ↑ Bryson Gwiyani-Nkohma (2006). Towards an African historical thought: Cheick Anta Diop's contribution (p. 108). Journal of Humanities, Vol 20, No.1.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Kevin Shillington (2004). Encyclopedia of African History: Volume 1 (A-G): 'Diop, Cheikh Anta (1923-1986)' (pp. 356-357). Routledge. [LG]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Stephen Howe (1999). Afrocentrism: Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes: 'Cheikh Anta Diop' (pp. 163-192). London: Verso. [LG]