More languages

More actions

| Hattusa 𒄩𒀜𒌅𒊭 | |

|---|---|

| c. 1650 BCE–c. 1190 BCE | |

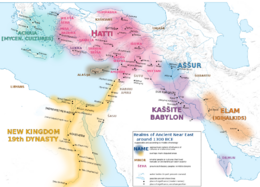

Location of the Hattusa and its vassals (pink) in 1300 BCE | |

| Capital | Hattusa |

| Official languages | Hittite |

| Common languages | Hattic Luwian |

| Dominant mode of production | Slavery |

| Government | Monarchy |

| History | |

• Established | c. 1650 BCE |

• Dissolution | c. 1190 BCE |

| Population | |

• Estimate | 200,000 |

Hattusa, commonly known as the Hittite Empire, was a Bronze Age kingdom in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey).[1]

History[edit | edit source]

Old Kingdom[edit | edit source]

The original inhabitants of Anatolia were the Hatti, who spoke a non-Indo-European language. Indo-European Hittites invaded at the start of the second millennium BCE and assimilated the native population. In the mid-17th century BCE, Labarna I unified the Hittites and conquered much of eastern Anatolia. His grandson, Mursili I, seized Halpa (Aleppo) and allied with the Kassites to sack Babylon in 1595 BCE. He was assassinated shortly after.[1]

The Hittites suffered from internal warfare and palace coups for a century. At the end of the 16th century BCE, King Telipinu created a law that defined the order of succession.[1]

New Kingdom[edit | edit source]

The Hittites waged endless wars between the late 15th and 13th centuries. Suppiluliuma I finally conquered Mitanni after a long war.[1]

Wars with Egypt[edit | edit source]

After conquering Mitanni, the Hittites fought with Egypt over control of Syria. Suppiluliuma allied with the Syrian Habiru tribes and led an offensive into Syria and Palestine. Because the Egyptians were distracted by Akhenaten's religious reforms, ignored the Syrians' requests for support.[1]

After Akhenaten's death, the widow of Pharaoh Tutankhamen sent a message asking to marry one of Suppiluliuma's sons. He sent a Hittite prince to Egypt, but the Egyptian nobles murdered him on the way to avoid having a Hittite pharaoh. The Egyptians and Hittites went to war again, fighting an inconclusive battle at Qadeš between the forces of Muwatalli II and Ramessu II. 17 years later, Ramessu signed a peace treaty with Hattusili III and married his daughter.[1]

Collapse[edit | edit source]

After making peace with Egypt, the Hittites were weak and asked Egypt for support against invading Anatolian tribes. At the end of the 13th century BCE, these tribes conquered Syria and Anatolia and destroyed the Hittite Empire.[1]

Government[edit | edit source]

All free men capable of bearing arms could participate in an assembly called the pankus. The king could not execute his relatives without permission of the pankus, and the property of the executed was inherited by his heirs and could not be confiscated. If the king violated these rules, the pankus could sentence him to death.[1]

Laws had different punishments depending on whether a crime was premeditated, but punishments were generally less harsh than in other countries at the time. Slaves who disobeyed their owners were executed. Laws also regulated marriage and inheritance.[1]

Army[edit | edit source]

Much of the free population was required to serve in the army. The Hittites used light two-wheeled chariots with a crew of three men. It took seven months to train horses for cavalry use.[1]