More languages

More actions

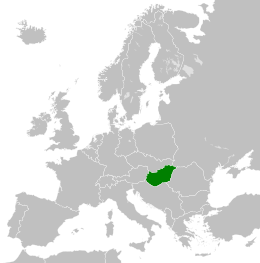

| Hungarian People's Republic Magyar Népköztársaság | |

|---|---|

| 1949–1989 | |

| |

| Capital | Budapest |

| Official languages | Hungarian |

| Dominant mode of production | Socialism |

| Government | Marxist-Leninist state |

• 1949–1956 | Mátyás Rákosi |

• 1956–1988 | János Kádar |

• 1988–1989 | Károly Grósz |

| History | |

• 1949 Constitution | 1949 August 20th |

| Area | |

• Total | 93,011 km² |

| Population | |

• 1970 estimate | 10,322,099 |

| Currency | Hungarian forint |

The Hungarian People's Republic was a socialist state ruled by a Marxist-Leninist government from 1949 to 1989, under the governing of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party. It is also the Warsaw Pact country with perhaps the fondest recollection among the people; polls in recent years have found upwards of 70% of Hungarians feel that life was better under socialism.

History[edit | edit source]

Background[edit | edit source]

See main article: Kingdom of Hungary (1920–1946)

Prior to the establishment of the Hungarian People's Republic, Hungary was a semi-feudal country, with very little industrial development and remarkably low quality-of-life. However, despite turbulent conditions, the socialist system still managed to rapidly develop Hungary's economy.[1] Hungary had been under fascist rule for 25 years and was an ally of Nazi Germany.[2]

Foundation[edit | edit source]

Beginning in 1948, an industrialization policy based on the Soviet-style planned economy changed the economic character of the country. A centrally-planned economy was introduced, and millions of new jobs were created in industry (notably for women) and, later, in services. The country had a severe lack of natural resources, which forced them to depend almost entirely on Soviet imports.[3]

Although Soviet-type economic modernization generated rapid growth, it was based on an early 20th-century structural pattern. The heavy industries of iron, steel, and engineering were given the highest priority, while modern infrastructure services, and communication were neglected. New technologies and high-tech industries were underdeveloped and further hampered by Western restrictions on the export of modern technology to the Soviet bloc.

Counterrevolution attempt[edit | edit source]

See main article: Hungarian counterrevolution of 1956

In October 1956, fascist gangs began an uprising and lynched Communists and their supporters. Prime Minister Imre Nagy succumbed to right-wing pressure, leading to a Soviet intervention. Yuri Andropov, Anastas Mikoyan, Mikhail Suslov, and Georgy Zhukov directed Soviet troops against the counterrevolutionaries, and János Kádár took power as General Secretary.[2]

Kádár era[edit | edit source]

The 1960s saw the state focusing on further expanding industry.[4] After this period, the economy shifted focus towards consumer production with the introduction of an economic reform plan known as the New Economic Mechanism (NEM), which somewhat restored the role of market forces, while retaining state ownership over the means of production, distribution, and exchange.[5] Kádár introduced decentralization and some forms of private enterprise.[2]

This time was marked by high rates of economic growth. Hungary reached the level of a middle-developed country.[6] By the mid-to-late 1980s, Hungary had achieved a very high standard of living compared to the pre-communist era. Food availability was high, and selection was relatively diverse.[7]

Hungarians also had high rates of ownership for various consumer goods, and the quality of goods was increasing as well.[8]

Despite these good statistics, the Hungarian economy was not free from problems; an over-reliance on Soviet orthodoxy (particularly in the early years) caused Hungary to lean heavily on the development of heavy industry, ignoring other forms of production which would have better suited the country's material conditions. In addition, the country's enterprises and farms suffered from low levels of relative productivity, which contributed to a slowing of growth in the 1980s.

In 1982, Hungary became the second Eastern Bloc country to join the IMF. This was a tremendous mistake, as various loan conditions during the 1980s eventually contributed to the collapse of the socialist system, and its replacement with a brutal strain of capitalism.

Counterrevolution[edit | edit source]

East German border crossings[edit | edit source]

On 2 May 1989, Hungary removed the barbed wire from its border with Austria. Hungarians had been able to visit Austria since long before, and East Germans were still not allowed into Austria. In July, a few dozen East German tourists tried to drive across the border but were turned around by Hungarian border guards. Many of them hid in the West German embassy in Hungary. On 19 August 1989, a descendant of the Austrian emperor invited 600 Germans in Hungary to cross the border into Austria. On 11 September, Hungary broke its treaty that agreed to repatriate East Germans and let 12,000 of them into West Germany. The GDR then began requiring special permission for its citizens to travel to Hungary.[9]

Living standards[edit | edit source]

Healthcare[edit | edit source]

Healthcare in pre-communist Hungary was of low quality, and the population suffered from poor health and low life-expectancy. However, after the establishment of the Hungarian People's Republic, healthcare conditions began to improve significantly. The US Federal Research Division reports:

After the communist government assumed power in Hungary, it devoted much attention to meeting the specific health care and social security needs of the population. In comparison with pre-war standards, the average citizen received far better health care and social assistance as a result of the government's policy.

The Encyclopedia Britannica notes:

Following World War II, health care improved dramatically under state socialism, with significant increases in the number of physicians and hospital beds in Hungary. By the 1970s, free healthcare was guaranteed to every citizen.

The social welfare system was also improved significantly, providing coverage to the vast majority of working people in Hungary. The US Federal Research Division notes:

In the late 1980s, the country's pension system covered about 85 percent of the population falling within pensionable ages. Male workers could qualify for pensions at the age of sixty, female workers at the age of fifty-five.

These advances are confirmed by the Encyclopedia Britannica:

A broad range of social services was provided by the communist government, including child support, extensive maternity leave, and an old-age pension system for which men became eligible at age 60 and women at age 55.

However, these improvements in social welfare came with a strange downside. As people began to live longer, and access to social welfare was expanded, the system was placed under more strain. The US Federal Research Division states:

The number of pensioners had increased rapidly since the end of World War II as people lived longer and as pension coverage expanded to include additional segments of the population.

In addition, various social ills, such as alcoholism, had begun to pose a problem for public health:

In the mid-1980;s, the authorities were also discussing the growing incidence of substance abuse. The incidence of alcoholism had increased during the previous generation, and a high percentage of suicide victims were alcoholics. As of 1986, consumption of alcohol per person per year was 11.7 liters; consumption of hard liquor (4.8 liters per person) was the second highest in the world.

To compound these issues, the Hungarian government spent a worryingly low percentage of GNP on healthcare:

Western analysts estimated that Hungary spent only 3.3 percent of its gross national product specifically on health service (the 6 percent figure listed in most statistical data actually included some social services). This percentage was the lowest of any East European country except Romania (in comparison, the United States spent 11 percent of GNP on health care).

Despite these problems, the socialist system in Hungary objectively provided clear benefits to the people in terms of healthcare and social welfare. There are a number of important lessons that we can learn from the Hungarian experience:

- It is essential that the proper resources be dedicated to healthcare and social welfare. Austerity benefits nobody on these issues, because the resulting decline in quality and availability will lead to instability and unrest, not to mention a reduction in living standards. The dictatorship of the proletariat must put the needs and interests of the proletariat as a top priority; otherwise, what's the point?

- It is also essential that a socialist government should take steps to resolve social problems such as alcoholism and drug addiction, which contributed massively to declining health throughout the Eastern Bloc in the 1970s and 1980s. The importance of these issues can be seen by contrasting the Eastern Bloc with other socialist countries, such as Cuba, which does not have such widespread substance abuse issues, and which has seen steady and stable improvements in health outcomes for decades (even during the "special period" following the fall of the USSR).

- Despite these factors, the socialist system in Hungary did manage to vastly improve the health of the population, as well as working people's access to social welfare. These improvements should not be ignored.

Education[edit | edit source]

Pre-communist Hungary had a highly elitist educational system, largely dominated by religious institutions. The US Federal Research Division reports:

Before the communist assumption of power in 1947, religion was the primary influence on education... The social and material status of students strongly influenced the type and extent of schooling they received. Education above the elementary level was generally available only to the social elite of the country. In secondary and higher-level schools, a mere 5 percent of the students came from worker or peasant families. Only about 1 or 2 percent of all students entered higher education.

However, after the Communists came to power, the educational system was drastically reformed. The Encyclopedia Britannica notes:

All this changed after the communist takeover of Hungary following World War II. In 1948 schools were nationalized, and the elitist German style of education was replaced by a Soviet-style mass education, consisting of eight years of general school and four years of secondary education. The latter consisted of college-preparatory high schools that approximated the upper four years of the gimnázium as well as of the more numerous and diverse vocational schools (technikumok) that prepared students for technical colleges or universities but in most instances simply led directly to mid-level jobs.

The educational system was greatly expanded. The US Federal Research Division states:

Attendance at school was mandatory from age six to sixteen. All students attended general schools for at least eight years. Tuition was free for all students from age six up to the university level. Most students actually began their schooling at five years of age; in 1986 approximately 92 percent of all children of kindergarten age attended one of the country's 4,804 kindergartens. By 1980 every town and two-thirds of the villages had kindergartens. Parents paid a fee for preschool services that was based on income, but such institutions were heavily subsidized by the local councils or enterprises that sponsored them.

These reforms succeeded in drastically expanding the educational standards throughout Hungary:

By 1980 only 29 percent of males aged fifteen years or older and 38 percent of females aged fifteen years and older had not completed eight years of general school, compared with 78 percent of such males and 80 percent of such females in 1949. About half of the students who completed the general schools subsequently completed their education in two years, through vocational and technical training. The remaining students continued their studies in a four-year gymnasium or trade school.

However, the system suffered from similar problems to the healthcare and social welfare systems. Specifically, it was underfunded; Hungary spent a very low percentage of GNP on education compared to other countries, which resulted in shortages:

Critics noted, among other things, that although Switzerland spent 18.8 percent of its national budget on education, Brazil 18.4 percent, and Japan 19.2 percent, Hungary allotted only 6.6 percent of its state budget to education. In the 1980s, the country experienced shortages of both classrooms and teachers, so that primary- school classes sometimes contained up to forty children. In many areas, schools had alternate morning and afternoon school shifts in order to stretch facilities and staff. Moreover, not all teachers received proper training.

Tourism[edit | edit source]

800,000 East Germans visited Hungary every year and hundreds of thousands more passed through Hungary on their way to other countries.[9]

Post-socialist nostalgia[edit | edit source]

Despite the issues of the Hungarian People's Republic, many people in Hungary have since found themselves longing for the return of the socialist system. A poll conducted by Pew Research Center found the following:

A remarkable 72% of Hungarians say that most people in their country are actually worse off today economically than they were under communism. Only 8% say most people in Hungary are better off, and 16% say things are about the same.

Even reactionary news sources have been unable to ignore the favorable opinion that many Hungarians have of the old socialist system. The Daily Mail (one of the most hard-line right-wing papers in Britain) published an article by a woman from Hungary, which made some interesting statements:

When people ask me what it was like growing up behind the Iron Curtain in Hungary in the Seventies and Eighties, most expect to hear tales of secret police, bread queues and other nasty manifestations of life in a one-party state.

They are invariably disappointed when I explain that the reality was quite different, and communist Hungary, far from being hell on earth, was in fact, rather a fun place to live.

The communists provided everyone with guaranteed employment, good education and free healthcare. Violent crime was virtually non-existent.

The author notes that cultural life was expanded to include all Hungarians, not only the upper-classes:

Culture was regarded as extremely important by the government. The communists did not want to restrict the finer things of life to the upper and middle classes - the very best of music, literature and dance were for all to enjoy.

This meant lavish subsidies were given to institutions including orchestras, opera houses, theaters and cinemas. Ticket prices were subsidized by the State, making visits to the opera and theater affordable.

'Cultural houses' were opened in every town and village, so provincial, working-class people such as my parents could have easy access to the performing arts, and to the best performers.

She notes that advertising and consumerist culture was virtually nonexistent in Hungary:

Although we lived well under 'goulash communism' and there was always enough food for us to eat, we were not bombarded with advertising for products we didn't need.

She laments that the perspectives of ordinary working-class people from the Eastern Bloc are typically ignored by the West:

When communism in Hungary ended in 1989, I was not only surprised, but saddened, as were many others. Yes, there were people marching against the government, but the majority of ordinary people - me and my family included - did not take part in the protests.

Our voice - the voice of those whose lives were improved by communism - is seldom heard when it comes to discussions of what life was like behind the Iron Curtain.

Instead, the accounts we hear in the West are nearly always from the perspectives of wealthy emigres or anti-communist dissidents with an axe to grind.

Finally, she notes that the losses of the post-communist era have vastly exceeded any potential gains:

People no longer have job security. Poverty and crime is on the increase. Working-class people can no longer afford to go to the opera or theater. As in Britain, TV has dumbed down to a worrying degree - ironically, we never had Big Brother under communism, but we have it today. Most sadly of all, the spirit of camaraderie that we once enjoyed has all but disappeared. In the past two decades we may have gained shopping malls, multi-party ' democracy', mobile phones and the internet. But we have lost a whole lot more.

By actually listening to the accounts of people who lived under socialism, as well as examining the polls, we can see what the working-class truly feel about socialism, as well as the ruthless capitalism that succeeded it.

Bibliography[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ “Despite war, depression, revolution, foreign occupation, and periods of near chaos, Hungary's economy has advanced in the twentieth century from a near-feudal state to a middle-level stage of industrial development.”

Hungary: a country study (1990). Federal Research Division. [LG] - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Roger Keeran, Thomas Kenny (2010). Socialism Betrayed: Behind the Collapse of the Soviet Union: 'Two Trends in Soviet Politics' (pp. 49–50). [PDF] iUniverse.com. ISBN 9781450241717

- ↑ “The country's general lack of raw materials has necessitated foreign trade, a concern that has dominated the economic policies of Hungarian governments since 1918, when the country lost much of the territory it held prior to World War I [...] The Soviet Union was Hungary's principal supplier of raw materials.”

Hungary: a country study (1990). Federal Research Division. [LG] - ↑ “During the 1960's, the government gave high priority to expanding the industrial sector's engineering and chemical branches. Production of buses, machine tools, precision instruments, and telecommunications equipment received the most attention in the engineering sector. The chemical sector focused on artificial-fertilizer, plastic, and synthetic-fiber production. The Hungarian and Comecon markets were the government's primary targets, and the policies resulted in increased imports of energy, raw materials, and semi-finished goods.”

Hungary: a country study (1990). Federal Research Division. [LG] - ↑ “By the mid-1960's, the government realized that the policy for industrial expansion it had followed since 1949 was no longer viable. Although the economy was growing steadily and the population's living standard was improving, key factors limited further growth... The government introduced the NEM in 1968 in order to improve enterprise efficiency and make its goods more competitive on world markets.”

Hungary: a country study (1990). Federal Research Division. [LG] - ↑ “From 1968 to 1972, the NEM and a favorable economic environment contributed to good economic performance. The economy grew steadily, neither unemployment nor inflation was apparent, and the country's convertible-currency balance of payments was in equilibrium as exports to Western markets grew more rapidly than its imports. Cooperative farms and factories rapidly increased production of goods and services that were lacking before the reform. By about 1970, Hungary had reached the status of a medium-developed country. Its industry was producing 40 to 50 percent of the gross domestic product, while agriculture was contributing less than 20 percent.”

Hungary: a country study (1990). Federal Research Division. [LG] - ↑ “In 1986 Hungary's per-capita meat consumption was the highest in Eastern Europe, while its egg consumption ranked among the highest. Per capita consumption of meat, fish, milk and dairy products, eggs, vegetables, potatoes, coffee, wine, beer, and hard liquor all increased significantly between 1950 and 1984.”

Hungary: a country study (1990). Federal Research Division. [LG] - ↑ “By 1984, 96 out of 100 households owned a washing machine, every household owned a refrigerator, and the ratio of television sets to households was 108 to 100. The quality and variety of durable consumer goods on sale had also improved.”

Hungary: a country study (1990). Federal Research Division. [LG] - ↑ 9.0 9.1 Austin Murphy (2000). The Triumph of Evil: 'A Detailed Autopsy of the Collapse of the Superior System in the Divided Germany' (pp. 133–5). [PDF] Fucecchio: European Press Academic Publishing. ISBN 8883980026