More languages

More actions

This article is missing sources. Please do not take all information in this article uncritically, since it may be incorrect. If you have a source for this page, you can add it by making an edit. |

| Federative Republic of Brazil República Federativa do Brasil | |

|---|---|

| |

| Capital | Brasília |

| Largest city | São Paulo |

| Demonym(s) | Brazilian |

| Government | Federal presidential bourgeois state |

• President | Lula da Silva |

• President of the Chamber of Deputies | Arthur Lira |

• President of the Federal Senate | Rodrigo Pacheco |

• President of the Supreme Federal Court | Luís Roberto Barroso |

| History | |

• Proclamation of the Empire of Brazil | 1822 September 7th |

• Proclamation of the Republic of Brazil | 1889 November 15th |

• US-backed right-wing military dictatorship | 1964 April 1st |

• Redemocratization | 1985 March 15th |

| Population | |

• 2022 census | 203,080,756 |

| Labour | |

• Labour force | 86.621 million[1] |

• Labour force participation | 56.8%[3] |

• Occupation | agriculture: 9.4% industry: 32.1% services: 58.5%[1] |

• Unemployment rate | 14.7%[2] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | US$1.84 trillion[4] |

• Per capita | US$8,717.18[5] |

| Exports | 2019 estimate |

• Value | US$263 billion[6] |

• Commodities | soybeans, crude petroleum, iron, corn, wood pulp products[1] |

• Partners | China (28%), United States (13%)[1] |

| Imports | 2019 estimate |

• Value | US$269 billion[7] |

• Commodities | refined petroleum, vehicle parts, crude petroleum, integrated circuits, pesticides[1] |

• Partners | China (21%), United States (18%), Germany (6%) |

| External debt | US$684.6 billion (20th) |

| Gini (2018) | 53.9% (9th) |

| HDI (2019) | 0.765 (84th) |

| Currency | Brazilian real (BRL) |

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in Iberoamerica by population and area. It is bordered to the south by Uruguay and Argentina, to the southwest by Paraguay and Bolivia, to the west by Peru and Colombia and to the north by Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname and the French colony of Guiana. It is the most populous country in its continent. It is a dependent capitalist country.[8]

From 2019 to 2022, the country was under the government of Jair Bolsonaro, who promoted and enacted policies of privatization of state-owned enterprises led by the Chicago Boys member Paulo Guedes. It was a de facto military, fascist government, composed of 6.1 thousand military personnel in public offices,[9] more than 2.3 thousand irregularly.[10] Attaching particular importance to strengthening its position in Iberoamerica, the Brazilian government seeks to act as a leader of countries on the American continent.

History[edit | edit source]

Pre-colonization (~60,000 BCE – 1500)[edit | edit source]

The appearance of humans on the territory of Brazil goes back to the Neolithic Age. Before the beginning of the 16th century, the territory of Brazil was inhabited by indigenous tribes: Tupi, Guarani, Tupinambas, Botokuds, Tamoyos, Koroados, etc. All of them were at the stage of tribal organization and lived in small communities. The tribal aristocracy was just beginning to form, and most of the tribes were nomadic. The Tupi-Guaranis led a settled way of life. In their communities, priests and chiefs were distinguished and had some personal property, including domestic slaves.[citation needed]

Colonization period (1500–1822)[edit | edit source]

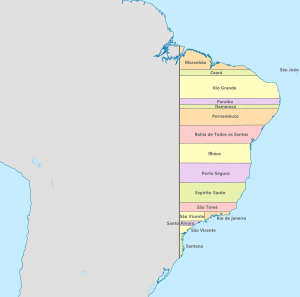

In 1500, the Portuguese Empire sent the navigator Pedro Álvares Cabral on the coast of Brazil and declared the land he discovered to be the possession of Portugal. The Portuguese took the valuable mahogany pau-brasil, a commodity which would eventually give name to the country. The territory of Brazil was later occupied by Jesuits, clerical figures which planned to convert the native peoples. The Jesuit order was instrumental in establishing slavery and patriarchal clan relations. For the most part of the 15th century, the territory of Brazil was divided into 13 captaincies[a] whose owners were usually from Portuguese feudal nobility, received as beneficiaries from the king.

During the 16th century, the conquest of the territory of Brazil took place in the context of an intense struggle of the Portuguese Empire with its rivals, mainly France and Holland. In 1630, the Dutch managed to capture the territory of the Pernambuco captaincy, but in 1654 they were expelled from the territory of Brazil. On the colonized territory, from the 16th century, big landowners' estates (sesmaria) with the use of feudal and slave forms of exploitation of natives and Africans started to form (the first Africans were brought to Brazil in the 1530s).

Production of goods imported from the metropolis (wheat, vegetable oil, wine, etc.) was forbidden in the colony. Only cotton, rice, corn were cultivated, but sugar cane was the main crop. Sugar cane plantations required large amount of labor. From the late 17th century the importation of slaves from Africa intensified, especially in connection with the discovery of gold and diamonds. The brutal exploitation of slaves on the plantations led to a large mortality rate. Indians and blacks put up stubborn resistance to their oppressors. In 1630 escaped slaves created in one of the remote regions of the Pernambuco state - the Republic of Palmaris that existed until 1697. In the second half of the 17th century Portugal continued the centralization of the colonial government and the prohibitive trade policy. The local government had limited power, trade with the colony was given to a small number of companies, the main role among which played the Portuguese General Company of the Brazilian Trade, founded in 1649. From 1658 it raised sharply the taxes collected in the colony, in 1665 it introduced a salt monopoly. In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the first speeches of Brazilian colonists against the Portuguese authorities took place (1684, 1720). To contain the growth of discontent, the Portuguese government allowed the foundation of manufactories and expelled the Jesuits (1759). However at the end of the 18th century Portugal forbade the foundation of manufactures, the building of ships, and printing.

Gold and diamond mining became very important during this period, turning Brazil into the richest colony in Portugal. The so-called gold rush stimulated the foundation of new cities and the building of roads. Rio de Janeiro became the main point linking Brazil with the outside world. In 1763, the capital was moved from Salvador to Rio de Janeiro. The contradictions between Banyan and the metropolis aggravated at the turn of the 18th-19th centuries, which put all possible obstacles in the way of its economic, political, and cultural development. In 1789, a conspiracy led by Tiradentis was uncovered in the province of Minas Gerais. The conspirators intended to establish an independent republic and the gradual abolition of slavery. In 1797 rebellions against Portugal broke out in the province of Bahia, in which soldiers and the urban poor, including mulattoes and Africans, participated. In 1807 in connection with the occupation of Portugal by Napoleon's troops, the Portuguese royal court fled to Rio de Janeiro. The stay of the court had as a consequence a number of innovations. The captaincies came to be called provinces. Brazilian ports were opened to trade with other countries. Newspapers, magazines, a Brazilian bank, a national library and museum were founded. The royal court depended entirely on British patronage. By the treaty of 1810, Great Britain obtained great advantages in trade with Brazil The stay in Brazil of the royal court, the Portuguese army, English advisers and the expenses connected with it increased the tax oppression and caused a further growth of discontent among the working masses of Brazil with Portuguese domination. In 1815 Brazil received the status of a kingdom, becoming part of the "United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil, and the Algarve". Formally, Brazil ceased to be a colony, but Portuguese authorities were still in charge in Brazil. The movement against the rule of the colonizers did not weaken. In 1817, a rebellion broke out in the province of Pernambuco which then spread to Ceará, Paraíba, Maranhão and Alagoas. The rebels proclaimed the province of Pernambuco a republic, formed a provisional government, and appealed to all the people of Brazil to end Portuguese rule and establish an independent Brazilian republic; the revolutionary government lasted 72 days.[citation needed]

The bourgeois revolution of 1820 in Portugal led to a new upsurge in the movement for the independence of Brazil. King João VI was forced to leave Brazil (1821), leaving his son Pedro I as regent of Brazil The liberation movement under the slogan "Freedom or Death!" spread throughout Brazil On September 7, 1822, Pedro I declared Brazil an independent empire. The day became a national holiday.[11]

Empire era (1822–1889)[edit | edit source]

In March 1824 the first constitution of the country came into force, according to which Brazil was proclaimed a constitutional monarchy. Portugal was forced to recognize the independence of Brazil (1825). The three-hundred-year colonial period ended, but the monarchy in Brazil survived. Under Emperors Pedro I of Brazil (1822-31) and his son Pedro II (1831-89) the country became economically dependent on Great Britain. In the peculiar combination of slave-holding, feudal and nascent capitalist production relations, slave-holding relations prevailed in the first half of the 19th century, especially in the main branches of Brazil economy: coffee and sugar production and in the mining industry. The political development of Brazil was marked by the persistent struggle of the masses against the monarchical regime and reaction, for a federal democratic republic and the abolition of slavery. In 1824-30, there were continuous uprisings of African slaves in the province of Bahia. In June 1831, a popular republican uprising broke out in the province of Rio de Janeiro. In 1833-1849 a wave of armed popular uprisings broke out in most provinces demanding the establishment of a democratic republic. The largest were the "farrapos" (ragamuffins) in the province of Rio Grande do Sul (1835- 1845) and the "praieiros" (coast-dwellers) in the province of Pernambuco (1848-1849).

In the second half of the 19th century, with the abolition of the slave trade, slave labour was gradually replaced by free labour. The new production relations led to a more noticeable development of industry and agriculture. The process of formation of capitalist relations was accelerated by the growth of European immigration that began in the 50s and became particularly widespread in the 80s-90s.

From 1865 to 1870, Brazil, in alliance with Argentina and Uruguay, fought a war for the dismemberment of Paraguay. During the war, the abolitionist movement intensified. In 1888, the so-called Golden Law on the abolition of slavery was issued. Anti-monarchist republican movement, which developed in parallel with the abolitionist movement, was led by the Republican Party (founded in 1869). There were popular anti-monarchist demonstrations in the country. On November 15, 1889 Emperor Pedro II was overthrown and Brazil was proclaimed a federal republic. The Constituent Assembly convened in February 1891 adopted a constitution similar to the U.S. Constitution. The provinces were transformed into states. The capital, Rio de Janeiro, was made a federal district.[11][12][13]

Republic era (1889–1964)[edit | edit source]

With the proclamation of the republic, political power in the country remained in the hands of the landlords and the big bourgeoisie, connected with foreign, mainly English, capital. The government, protecting the interests of the ruling classes, brutally cracked down on the democratic movement. In 1896-97 a peasant land movement broke out in Bahia, near Canudus. It was suppressed by the government forces, but the peasants' fight for the land continued. With the abolition of slavery the capitalist development of Brazil accelerated considerably. The rapid growth of enterprises in towns led to an increase in the number of workers. The first trade unions and workers' organizations began to appear at the turn of the 19th-20th centuries. In 1892 a workers' congress was held in Rio de Janeiro, which attempted to establish a workers' party. The Socialist Center was founded in Santos that year and led the May Day demonstrations of 1895 in Santos and São Paulo. By 1896 there were several Marxist circles in the country. A socialist newspaper, Sosialista (O Socialista), began to be published in São Paulo. In 1905-07 there were workers' demonstrations and strikes in Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Santos, and in 1906 a workers' congress was held in Rio de Janeiro.

Foreign capital, which had penetrated the economy of Brazil, directed it in a direction beneficial to its interests. English and American monopolies seized fertile land. Coffee, cotton, and sugar took a leading place in the economy of Brazil In 1910 Brazil became a member of the Pan American Union. From that time American capital began to penetrate strongly into the Brazil economy, becoming after the World War I, 1914-1918 the main rival of British capital. From 1917 Brazil participated in the war on the side of the Entente.

Under the influence of the Great October Socialist Revolution in Russia, the workers' movement in Brazil began to rise. In mass demonstrations and rallies workers openly expressed their sympathy for the ideas of the Russian revolution. In large cities, Marxist groups (socialist and communist circles and leagues) began to be created. In March 1922 the Brazilian Communist Party (BCP) was founded. In July 1922 there was an uprising of the capital's garrison in the Copacabana Fortress. In July 1924 the garrison of São Paulo rebelled. The city's masses supported the rebels. The rebels seized the city and held it for three weeks. Under the influence of events in Sao Paulo rebellions broke out in many states of Brazil. L. C. Prestes, who led the rebellion in the south of Brazil, led with continuous fighting the rebel column to the N. of the country (October 1924-February 1927). The governments of A. Bernardis (1922-26) and V. Luis Pereira (1926-30) suppressed the uprisings.

The economic crisis of 1929-33 hit Brazil with great force. During the crisis years, 2.4 million tons of coffee were destroyed as prices for all of Brazil's main exports - coffee, cocoa, cotton, and livestock products - plummeted on the world market. The working class suffered from unemployment. The crisis revealed the extreme backwardness of the social structure and Brazil's dependence on foreign capital. On the eve of the presidential elections of 1930, two hostile political factions had formed: the Conservative Concentration, which represented the interests of the landowners who relied on English imperialism, and the Liberal Alliance, which represented the bourgeoisie and the bourgeoisized landowners connected with the US imperialists. As a result of the armed struggle for power in November 1930 the Liberal Alliance supporter, J. Vargas, won and formed an interim government. In fact, a dictatorship was established in Brazil Vargas, who, depending on the situation, changed the methods of government in the interests of the bourgeoisie and landlords. The German and Italian monopolies intensively penetrated the economy of Brazil German monopolies acquired controlling stakes in a number of large manufacturing enterprises, iron mines, and vast lands in Riachan (on the N.-E.); the "German Bank for South America" established in Brazil 300 of its branches. The economic expansion of German imperialism strengthened fascist elements in the political life of the country. The Fascist party, the Integralist Action (founded in 1933), was active in Brazil The working class and the masses offered resolute resistance to the onslaught of fascism. In March 1935 the anti-fascist forces united into the National Liberation Alliance (NLA), which put forward the task of fighting against fascism and imperialism and for the implementation of an agrarian reform. In July the government forbade the activities of the NLA. In November 1935 armed uprisings took place under the leadership of the ELA in Rio de Janeiro, Niteroi, Recife, and Natal, drowned in blood. Brazil was declared a state of siege, tens of thousands of revolutionaries were arrested, including L. C. Prestes and other Communist Party leaders. The organization of corporate unions dependent on the government was intensified. In 1936 Vargas issued decrees on minimum wages, nationalization of the transport company Lloyd Brazileiro, owned by English capital, pensions for industrial workers, and in 1938 on nationalization of oil sources and wage increases for certain categories of workers. These measures were conditioned both by the struggle of workers for their rights and interests and by the development of capitalism in Brazil As a spokesman for the bourgeoisie, Vargas understood the need to increase the role of the state for the country's economic development.

In November 1937 Vargas dissolved the congress and promulgated a constitution proclaiming Brazil "a new state." In December, all political parties were dissolved. Vargas launched a social demagogy, portraying himself as the founder of a "new state of justice.

During World War II, 1939-45, the penetration of U.S. imperialism into Brazil intensified. In January 1941 an agreement was signed to send a U.S. military mission to Brazil In January 1942, Brazil broke off diplomatic relations with Germany and Italy and in August 1942 declared war on them (Brazil declared war on Japan on June 6, 1945). The defeat of the Fascist powers gave a powerful impetus to the development of the democratic movement in Brazil Under the pressure of the masses, the Vargas government had granted amnesty to political prisoners in the beginning of 1945, had allowed the political parties, including the Communist Party, to work and had established diplomatic relations with the USSR (April 2, 1945). In the same year several political parties were founded: the Social-Democratic Party, reflecting the interests of large latifundists; the National Democratic Union, uniting broad sections of the national bourgeoisie, led by the leaders of the so-called Western, anti-communist orientation, and the Brazilian Trabalist Party, representing the middle and petty bourgeoisie and a considerable number of workers.

Frightened by the growth of the democratic movement, the most reactionary circles in Brazil, closely affiliated with the United States, decided to overthrow the Vargas government. On October 29 Generals G. Monteiro and E. G. Dutra organized a military coup. Parliamentary and presidential elections were held in December, with considerable success for the Communists, who for the first time nominated their candidates in national elections. The government was headed by General E. G. Dutra (1946-51). In 1946 a new constitution was adopted, reflecting some of the democratic gains of the workers, the rights of the people to the subsoil wealth of Brazil However, already in May 1947 reaction went on the offensive. The government banned the activities of the BKP, the Union of Communist Youth (founded in 1943) and the Trade Union Confederation of Workers (founded in 1946). In October 1947 Brazil broke off diplomatic relations with the USSR, and in May 1949 the Movement of Supporters of Peace was banned in the country. The Dutra government followed the policy of militarization and the Cold War. U.S. direct investment in Brazil rose from $323 million in 1946 to $803 million in 1951. The capitulation to U.S. imperialism and the repressive regime aroused popular discontent. As a result of the unfolding nationalist movement, the Vargas government (1951-54) came to power again. Due to the poor state of the finances, Vargas received as early as 1952 a $300 million loan from the United States and opened up access to U.S. private capital investment. At the same time, in 1953 the Vargas government created the state oil company Petrobras, which established a state monopoly (with the participation of Brazilian private capital) for exploration, production, and refining of Brazilian oil, and in April 1954 it submitted to Congress a bill to create the state company Electrobras. The labor movement in Brazil was intensifying. In 1953 800 thousand workers took part in the strike struggle (in the preceding 5 years an average of 200-300 thousand people). The trade unions united over 1.3 million workers. In May 1954, under the pressure of the masses Vargas declared that the minimum wage of workers and employees was to be doubled in comparison with 1951. The reactionary circles of the latifundists, big capitalists and the military believed that Vargas's policy stimulated the development of mass popular uprisings and threatened the existing order. In August, a meeting of air force generals decided to demand Vargas's resignation as "the only means" to resolve the "national crisis." Vargas committed suicide. The military and reaction tried to establish a dictatorial regime in Brazil The people thwarted their plans with mass demonstrations. The government of J. Kubicek de Oliveira (1956-60) came to power, representing both patriotic figures and reactionary politicians connected with foreign, mainly American, capital. Often reactionaries were able to exert decisive influence on government policy. In 1957 the Kubitschek government signed an agreement with the United States on giving up Fernando de Noronha for a five-year term as a U.S. military base.

In the 1950s, Brazil had an automobile industry, increased oil production and refining, ferrous metal smelting, cement production, and power generation. From agrarian Brazil was transforming into an agrarian-industrial country with large industrial centers: São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Recife, etc. The opening of the new capital (April 21, 1960) - Brasilia - signaled the economic strengthening of the Brazilian bourgeoisie. However, many important sectors of the Brazilian economy remained in the hands of foreign capital, mainly the United States. Latifundia and backward relations persisted in agriculture.

In the 1960 elections, with the support of the bourgeoisie, latifundists, the Catholic Church, some social democrats and the Brazilian Trabalist Party, J. Cuadros was elected president. The Cuadros government charted a more independent foreign policy, took steps to establish diplomatic and trade relations with the USSR and other dependant countries, and strengthened the country's financial position. This caused discontent among reactionary circles connected with American monopolies. Under their pressure, Cuadros was forced to resign in August 1961. Nationalist forces opposed to the desire of reaction to establish a dictatorship in the country, achieved the accession to the presidency of Vice-President J. Goulart. Goulart's government which came to power in September 1961 (1961-64) restored diplomatic relations with the USSR. In October - November 1961, the National Liberation Front was founded which united the nationalist and patriotic forces of the country. In its activities, the Goulart government relied mainly on the national bourgeoisie and nationalist forces. It put forward a program of agrarian, financial, and banking reforms, education reform, etc. From December 1963 to March 1964, the Goulart government passed decrees restricting the export of profits from the country (not more than 10%) on invested foreign capital, establishing a state monopoly on oil and petroleum product imports, nationalizing oil refineries, nationalizing uncultivated land located within a 10-km strip along state railroads and highways and waterworks, canceling mining concessions (if companies do not exploit mines) and granting exclusive rights In the field of foreign policy, the Goulart government advocated general and complete disarmament and the peaceful coexistence of states with different socio-economic systems.[citation needed]

In 1961, centrist president Jânio Quadros resigned after seven months in office, leading to his anti-imperialist vice president, João Goulart, becoming president. Goulart supported agrarian reform and universal suffrage and was supported by Catholic bishops and members of student unions. The pro-imperialist bourgeoisie, connected with the U.S. monopolies, the latifundists, a certain part of the army, above all the reactionary generals and high officers, as well as the reactionary upper class of the Catholic Church, strongly opposed the measures of the Goulart government. Taking advantage of the ferment in the army, reaction turned to open action. The United States turned on him after he refused to ban leftists from his cabinet and the CIA began funding his opponents in October 1962.[14] On March 31, 1964 a military mutiny broke out in the state of Minas Gerais. As a result of the coup d'etat, a political-military group led by General U. Castelo Branco representing the interests of large landowners and financial-industrial groups connected with American monopolies came to power.[11][15][16][17]

Military dictatorship (1964–1985)[edit | edit source]

Soon after the coup, the military abolished the 1946 constitution and banned the General Confederation of Workers (CGT) and National Students' Union (UNE). Other unions were allowed, but their leadership was controlled by the government. In 1968, military leader Artur da Costa e Silva passed Institutional Act No. 5, removing all limits on the military dictatorship's power. More than 300 politicians, including former presidents Goulart, Cuadros, and Kubitschek, as well as BKP Secretary General L. K. Prestes, were deprived of their political rights for 10 years under this act. Under the dictatorship, 50,000 people were arrested, 7,000 were exiled, and over 400 were killed. Brazil's intelligence service, the SNI, was trained to torture dissidents by CIA agent Dan Mitrione. At two torture centers, the House of Death in Pétropolis and the Kerosene Nightclub in São Paulo, almost everyone who was tortured died.

On April 11 Castelo Branco, one of the organizers of the coup, was elected president. By decrees of military authorities and presidential decrees, the constitution of 1946 was practically abrogated, political parties were dissolved, the National Congress, state apparatus, army, educational institutions were purged, and control over trade unions was established. The Branco government (1964-67) disbanded the political parties and in 1966 it decreed the formation of two political groups: the National Union of Renewal and the Brazilian Democratic Movement, which was the legal opposition. In favor of U.S. interests, the government repealed the law restricting the export of profits from the country by foreign enterprises, severed diplomatic relations with Cuba, and participated in the U.S. intervention in the Dominican Republic. The Branco government repeatedly expressed solidarity with the U.S. ruling circles that unleashed military action against Vietnam in 1964, and provided material support to the Saigon regime in South Vietnam.

In March 1967 General A. da Costa e Silva became president. The new government (1967-69) represented basically the same military-political and social forces as the previous military government. The internal political course remained essentially unchanged. In 1967-68, the student movement and workers' struggle against the military regime and its wage blocking policy intensified. Part of the Catholic clergy also opposed the government. The so-called Broad Front of the Legal Opposition was also a political opponent of the government. In April 1968, the government banned its activities. Contradictions within the government and its main supporter, the armed forces, became acute. In December 1968, the parliament was dissolved, and the power went to the President. At the beginning of 1969 some more decrees were issued to expand the President's authority, but all that did not lead to normalization of the political situation in the country. In August 1969, due to the illness of Costa e Silva, power passed into the hands of a triumvirate of military ministers, which was in fact a military coup. In October, General Emílio Garrastazu Médici took power and ruled until 1974. He abolished the National Congress, gave all power to the presidency, and banned public demonstrations. In the mid-1970s, ten members of the Brazilian Communist Party (PCB) Central Committee were murdered and their bodies were hidden in a river. Almost all leadership of the PCB was arrested and 2,000 militants were tortured. PCB leader Elson Costa was tortured for more than 20 days and was burned alive after refusing to give information.[12][18][19]

Institutional Act 5 was repealed in 1978[19] and military rule ended in 1985.[20]

Indigenous genocide[edit | edit source]

With support from the World Bank, the junta displaced indigenous peoples to extract natural resources for Western capitalists. The Rural Indigenous Guard, which was created by the CIA, massacred indigenous communities. They killed thousands of people and bombed villages with napalm.[21]

Recent history (1985–present)[edit | edit source]

In 2002, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of the Workers' Party was elected president after building an alliance with centrists. Lula enacted social programs that reduced poverty and increased access to higher education. In 2010, Lula was succeeded by Dilma Rousseff. In 2014, an economic crisis began in Brazil and austerity measures were enacted. The right organized the impeachment of Rousseff and her vice president, Michel Temer, took power in 2016. In 2018, Lula was arrested and prevented from running for president. A left-wing coalition that included the PCB and the Socialism and Liberty Party supported the Workers' Party candidate Fernando Haddad. Haddad lost the election with 44.87% of the vote, and Jair Bolsonaro of the far-right "Brazil above Everything, God above Everyone" coalition won with 55.13% of the vote.[22]

Lula returned to power in January 2023 after winning the 2022 presidential election, and Bolsonaro fled to the United States. Bolsonaro's supporters attempted a coup against Lula days after he returned to the presidency.[23]

Art[edit | edit source]

In the 1920s there was a new visual art of Brazil (one of its sources - the movement "Week of Modern Art", Sao Paulo, 1922), in which the quest in the spirit of social realism is intertwined with subjectivist experiments, In painting next to the majestic folk images of C. Portinari and E. di Cavalcanti, folk and bright decorative paintings of Tarsila do Amaral and self-taught artist Janira, expressionism (L. Segal), abstractionism and the latest modernist trends were developed. The democratic graphic art of Brazil (O. Goeldi, K. Skliar, R. Katz) is characterized by spiritual expressiveness. For sculpture (B. Giorgi, V. Breshere) oscillation between vital national images and abstract fantasies is characteristic. In the decorative arts ceramics and painting of fabrics are distinguished.

Diverse types of folk art Brazil - Negro (figurines, multicolored clothing, household utensils in the traditions of African art) and especially indigenous (figural ceramics of Karage people, wooden figurines of Cadiuveo people, polychrome painting of huts of Tukano people, carved zoomorphic Carib benches, patterned weaving, feather products, weaving from palm leaves and many others). Common types of folk dwellings (including indigenous dwellings) are dugouts, huts (piled in humid areas), canopies made of palm leaves.[24]

Economy[edit | edit source]

Brazil exports $28.6B of soybeans (13.36%), $26.5B of iron ore (12.38%), $19.8B of crude petroleum (9.25%), $8.95B of raw sugar (4.18%), $6.69B of bovine meat (3.12%) and $123.5B of other products, totaling $214B in exports. These exports flow mostly towards China ($67.9B), United States ($21.9B), Argentina ($8.57B), Netherlands ($6.7B), and Canada ($4.39B).[25]

Politics[edit | edit source]

Class struggle in Brazil[edit | edit source]

In June 19th, 2021, protesters in over 400 cities in protest of the fascist Jair Bolsonaro government. Militants and activists gathered safely, respecting social isolation guidelines related to the COVID-19 pandemic.[26]

Police brutality[edit | edit source]

The Brazilian police killed at least 645 people in Rio de Janeiro in 2015. The police commit 20% of murders in Rio, and 80% of their victims are youth of African descent.[27]

Infrastructure[edit | edit source]

Demographics[edit | edit source]

In 2022, there were 1,693,535 indigenous people in Brazil making up a total of 304 ethnic groups and 274 languages. There are also 67 uncontacted tribes.[21]

Culture[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 CIA World Factbook (2020). Brazil – The world factbook (economy)

- ↑ Trading economics (2021). Brazil unemployment rate

- ↑ Trading economics (2021). Brazil labor force participation rate

- ↑ World Bank (2019). GDP (current US$) - Brazil

- ↑ World Bank (2019). GDP per capita (current US$) - Brazil

- ↑ World Bank (2019). Exports of goods and services (current US$) - Brazil

- ↑ World Bank (2019). Imports of goods and services (current US$) - Brazil

- ↑ Ruy Mauro Marini (1973). Dialética da dependência. [MIA]

- ↑ "Segundo TCU, 6,1 mil militares ocupam cargos no governo" (2020-07-17). Correio Braziliense. Retrieved 2022-07-16.

- ↑ "CGU aponta pagamentos e ocupações irregulares de 2,3 mil militares" (2022-07-12). Carta Capital. Retrieved 2022-07-16.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Rocha Pombu (1962). History of Brazil.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Meade, Teresa (2016). A History of Modern Latin America-1800 to the Present.

- ↑ Barman, Roderick J (1988). Brazil The Forging of a Nation, 1798–1852.

- ↑ Matias Spektor (2018). The United States and the 1964 Brazilian Military Coup (pp. 1–3). [PDF] Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History.

- ↑ Glinkin A. N. (1959). The Modern History of Brazil.

- ↑ Sivolobov A. M. (1959). Agrarian relations in modern Brazil.

- ↑ Faco P. (1962). Brazil of the XX century.

- ↑ Koval B. I. (1967). History of the Brazilian Proletariat (1857-1967).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Edmilson Costa (2019-12-23). "Remembering the Years of Lead under Brazil’s military rule: AI-5 never again!" Liberation School. Archived from the original on 2021-05-15. Retrieved 2022-06-21.

- ↑ Nicholas Stender (2021-09-08). "Bolsonaro’s coup threats rejected by people of Brazil" Liberation News. Archived from the original on 2021-12-20. Retrieved 2022-06-21.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Kit Klarenberg (2023-08-16). "Bolsonaro's Butchery: CIA Fingerprints Are All Over Brazil's Indigenous Genocide" MintPress News. Retrieved 2023-08-22.

- ↑ Silvio Rodrigues (2019-01-23). "Bolsonaro: A danger to Brazil, Latin America, and the whole world" Liberation School. Archived from the original on 2021-01-17. Retrieved 2022-06-05.

- ↑ "PSL statement: Far-right coup attempt vs. democracy in Brazil" (2023-01-08). Liberation News. Archived from the original on 2023-01-09. Retrieved 2023-01-11.

- ↑ Craven David (2002). Art and Revolution in Latin America, 1910-1990.

- ↑ "Brazil (BRA) exports, imports, and trade partners" (2020). Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC).

- ↑ Beatriz Drague Ramos (2021-06-21). For vaccines for all and against Bolsonaro, demonstrators take to the streets this Saturday [Portuguese: Por vacinas para todos e contra Bolsonaro, manifestantes vão às ruas neste sábado]. Ponte Jornalismo.

- ↑ "Brazil intensifies genocide against Africans in preparation for 2016 Olympic Games" (2016-08-04). The Burning Spear. Archived from the original on 2021-08-16. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

Notes[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Captaincies were administrative regions of the Portuguese Empire.