More languages

More actions

| Republic of Azerbaijan Azərbaycan Respublikası | |

|---|---|

| |

| Capital and largest city | Baku |

| Official languages | Azerbaijani |

| Demonym(s) | Azerbaijani Azeri |

| Dominant mode of production | Capitalism |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic |

• President | Ilham Aliyev |

• Vice President | Mehriban Aliyeva |

| Area | |

• Total | 86,600 km² |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 10,353,296 |

Azerbaijan, officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, is a country in the Caucasus region of Asia. It borders Russia to the north, Georgia to the northwest, Armenia to the west and Iran to the south as well as having an eastern coast on the Caspian Sea. The Aliyev dynasty has ruled the country since it seceded from the USSR in 1991, and 69% of Azerbaijanis aged 35 or older said life was better in the Soviet Union.[1] The Azerbaijani government receives weapons from Turkey and Israel.[2]

History[edit | edit source]

Prehistory[edit | edit source]

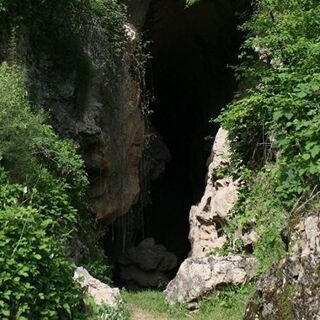

Azykh Cave[edit | edit source]

The territory of present-day Azerbaijan shows evidence of human settlement stretching back to the Paleolithic era, with Azykh Cave representing one of the oldest known settlements in Eurasia, where human activity dates back hundreds of thousands of years. However, the chaotic nature of history, marked by endless wars and natural disasters, has led to the loss of many historical documents and artifacts, leaving significant gaps in our understanding of Azerbaijan's ancient past.[3]

A more defined and notable chapter begins with the Khojaly-Gadabay culture (also known as the Ganja-Karabakh culture), which thrived from the Late Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age, approximately the 13th to the 7th centuries BC. This culture is known for its relatively complex burial rituals, where the dead were buried with their tools, metal weapons, gold jewelry, and a variety of ceramics, demonstrating their skills as potters and metalworkers. They established early urban settlements in the Caucasus, such as Uzerliktepa, which contained various workshops, animal shelters, and clay kilns.[4]

This settlement met a violent end. Evidence suggests Uzerliktepa was attacked and burned, likely around 700–600 BC. Archaeologists have found unburied human skeletons alongside abandoned weapons and valuables, indicating a swift and brutal assault that likely resulted in the population being slaughtered or enslaved. Historians speculate the attackers could have been invading nomadic tribes like the Scythians or Cimmerians, or perhaps the armies of a growing regional power such as Urartu. [5]

The decline of the Khojaly-Gadabay culture was not the end of development in the region. Instead, its people and their achievements were absorbed into the succeeding Kingdom of Caucasian Albania. This kingdom, which emerged around the 4th century BC, built upon the foundational elements established by earlier cultures: advanced metallurgy, proto-urbanization, a defined class structure, and established trade networks. In this way, the legacy of the Khojaly-Gadabay culture contributed to the creation of a more complex society in Caucasian Albania.[5]

Note: it's helpful to know that "Caucasian Albania" refers to an ancient kingdom in the Caucasus region, entirely different from the modern European country of Albania. It was established on the land that now forms Azerbaijan.[3]

Antiquity[edit | edit source]

Caucasian Albania[edit | edit source]

See main article: Aghwank

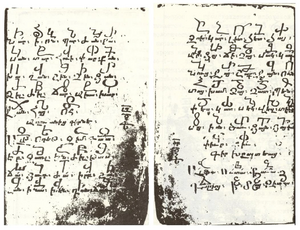

The Kingdom of Caucasian Albania (also known as Aghwank) emerged in the eastern Caucasus as a united state around the 4th to 2nd centuries BC. It was formed from a group of 26 different northeastern Caucasian tribes, each of which, according to the geographer Strabo, originally had its own king and language. This unification was the result of centuries of cultural development, building upon the foundations laid by advanced Bronze Age cultures like the Khojaly-Gadabay.[5]

For centuries, the political and economic center of Caucasian Albania was its capital, Qabala. Archaeological excavations reveal a large, fortified city with a citadel, residential districts, and craft workshops, indicating sophisticated urban planning and a thriving economy supported by its strategic location on major trade routes.[6]

While detailed records before the 5th century BC are rare, the region was absorbed into the Median Empire around that time. Both the Median and Achaemenid Empires recognized the strategic vulnerability of a narrow passage between the Caucasus Mountains and the Caspian Sea. An easy entrance for invading armies, particularly from nomadic Scythian tribes. To secure this frontier, they constructed a series of defensive fortifications in this area.[7]

The first historical record of Caucasian Albania comes from the Greek historian Arrian. He notes that during the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BC, the decisive confrontation between Alexander the Great and King Darius III, the forces of Caucasian Albania fought under the command of Atropates, a Persian satrap of Media.[8]

Following the fall of the Achaemenid Empire, Atropates retained his position due to his skill under Macedonian rule. After Alexander the Great's death in 323 BC, his empire was divided among his generals. Rather than submit to the new Macedonian authority, Atropates consolidated his territory in northwestern Media, establishing an independent kingdom that would become known as Atropatene, a name believed to be the root of "Azerbaijan".[8]

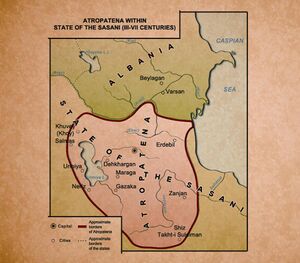

Atropatene[edit | edit source]

Atropatene, an ancient kingdom whose Persian name evolved into "Azerbaijan," was established in the region south of the Aras River. Its capital was the city of Ganzak, located in what is now the Iranian province of Azerbaijan. The kingdom was a hereditary monarchy with a multi-ethnic and multicultural society. While it included a diverse population, including Macedonian merchants and administrators from the previous Hellenistic period, the Persian Median people formed the majority, and the Zoroastrian faith was the dominant religion.[9]

The kingdom's economy was strong and diverse. Much of the region was fertile, supporting the cultivation of wheat, grapes for wine, and figs. Animal husbandry was also crucial, with a particular emphasis on breeding horses and camels. Strategically located along the western branch of the Silk Road, Atropatene became a hub for trade. Its networks stretched from the Caucasus and the Black Sea to Mesopotamia and India, facilitating the exchange of horses, textiles, precious metals, and other luxury goods. This commercial center was reflected in its blended culture, which combined deep Iranian traditions with elements of Hellenistic art and architecture.[10]

For approximately 150 years, Atropatene maintained its independence. Eventually, it became a vassal state of the Parthian Empire. It retained autonomy and were expected to provide military troops or funds to the Parthians during times of war.[11]

However, as the Parthian Empire gradually weakened and lost prestige, the nobility and clergy of Atropatene sided with the Sassanians. The kingdom was absorbed into the rising Sassanid Empire (Eranshahr) and was now known as a province named Āturpātakān. The hereditary dynasty was replaced by Sassanid governors, marking the end of Atropatene's independence.[11]

Āturpātakān / Adurbadagan[edit | edit source]

Following its annexation by the Sassanid Empire, Atropatene was reorganized and renamed Adurbadagan. The province was transformed into a key military fortress, its rugged terrain and fortifications making it a stronghold for defending the empire's northwestern borders against northern tribes.[12]

Beyond its strategic role, Adurbadagan also was used as a major spiritual center for the Zoroastrian faith. It became one of the empire's three holiest pilgrimage sites, due to the presence of Adur Gushnasp, one of the three great sacred fires. This fire temple, located at present-day Takht-e Soleymān, was unique; it was surrounded by fortifications and palaces, functioning as both a spiritual and military center. Notably, Adur Gushnasp is the only one of the three great fires whose ruins have been discovered by archaeologists.[5]

Administratively, Adurbadagan was the heart of the kust-i Adurbadagan, a dedicated military border district. The Spahbed oversaw the defenses of both Adurbadagan and the neighboring region of Arran, creating a defensive unit that could coordinate operations against invasions from the Caucasus and Central Asia. For approximately 425 years, the province served this dual purpose as a defensive base and a spiritual center of the Sassanid Empire.[11]

This era ended with the rise of the Rashidun Caliphate. After the defeat of the last Sassanid ruler, Yazdegerd III, the region was conquered and integrated into the Caliphate as a province (wilayah). It was then renamed to the Arabized version of its Sassanid name: Azarbayjan, a name that has endured to the present day.[13]

Medieviality[edit | edit source]

Azarbayjan[edit | edit source]

Under the Rashidun Caliphate, the region, now known by its Arabized name Azarbayjan, was allowed to keep its autonomy. Previous dynasties and governors continued to rule, maintaining their culture and Zoroastrian faith. Their religious temples and ceremonies remained untouched, in accordance with the Pact of Umar. This treaty granted non-Muslims the right to practice their religion in exchange for paying a 10% jizya tax, a policy that facilitated a coexistence of faiths. The region's only obligations to the Caliphate were providing local military support for its campaigns and serving as a strategic military frontier.[14]

The Caliphate introduced a few administrative systems, including the Diwan, a bureaucratic registry for state finances and soldier pay, and a formal legal system based on Islamic law to administer local justice. Economically, Azerbaijan became integrated into the global Islamic trade network, facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and technology. Over time, the influence and presence of Islam grew, leading to a gradual decline in Zoroastrianism and the slow linguistic evolution of the name to "Azerbaijan."[15]

The transition from the Rashidun to the Umayyad Caliphate was marked by the bloody civil war of the First Fitna. Thanks to the political neutrality of its governor, Azerbaijan was integrated into the new Umayyad rule without being drawn into the conflict. This period of relative stability continued as power later shifted to the Abbasid Caliphate, which loosened many strict policies of its predecessors. A big change was the incorporation of Turkish soldiers into the army, a decision that would pave the way for mass migrations into Azerbaijan in the centuries to follow.[16]

As the Abbasid Caliphate weakened due to internal strife and financial troubles, its distant provinces began to break away. In this power vacuum, Azerbaijan emerged as the origin for several dynasties, most of which were of Iranian origin. The most notable among them were the Sajids, Sallarids, Rawadids, and Shaddadids.[17]

Azerbaijan[edit | edit source]

The mass migration of Oghuz Turks, due to the Abbasid Caliphate's recruitment of Turkish soldiers and later accelerated by the Seljuk Empire's conquests, led to the gradual Turkicization of Azerbaijan. This demographic and linguistic shift was pivotal in forming the region's modern Turkic identity.[18]

While this transformation was intense, local autonomy was limited as authority rested with governors appointed by the Seljuk Empire. Because the Seljuks were also Muslims, the transition from the Caliphate to Seljuk rule was relatively smooth and did not create a cultural or religious conflict for the local population.[19]

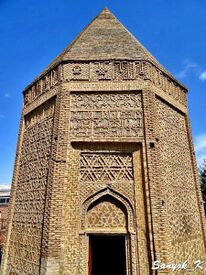

Azerbaijan became a power center for the Seljuk Empire, serving as a wealthy province and eventually the seat of the Eldiguzid dynasty, a powerful sub-empire that governed the region. Seljuk control, which lasted for approximately 170 years, left a significant architectural legacy, including two mausoleums: the Yusif ibn Kuseyir Mausoleum and the Momine Khatun Mausoleum.[20]

This period deepened Azerbaijan's connection to the Islamic world. However, the era of Seljuk dominance ended abruptly with the Mongol invasion. Azerbaijan was subsequently absorbed into the Ilkhanate, a Mongol state that continued to shape the region's history.[21]

Mongol Azerbaijan[edit | edit source]

The Ilkhanate era began with extreme violence. The initial Mongol invasions under commanders like Jebe and Subutai in the 1220s, followed by the full-scale campaigns of Hulagu Khan in the 1250s, were catastrophic for Azerbaijan. Cities like Ganja, Shamkir, and Baylaqan were besieged, looted, and destroyed, their populations massacred.[22]

The region was not a random target; its fertile pastures were highly prized by the Mongols as a logistical base for horse grazing and further campaigns into the Middle East. However, this period of destruction was followed by the Pax Mongolica, which created an economic revival. By securing the entire Silk Road, the Mongols enabled a flow of goods, ideas, and technologies. Azerbaijan, sitting at a crossroads, became a central hub in this network, with its capital, Tabriz, growing into one of the largest and most cosmopolitan cities in the world.[23]

Politically, the Ilkhanate initially centralized power under a non-Muslim Mongol elite, reducing the local Azerbaijani population, including the Turkic ruling class, to subjects. A massive shift occurred under Ilkhan Ghazan (1295–1304), whose conversion to Islam initiated the gradual assimilation of the Mongol rulers into the local Muslim society and restored Islam as the dominant political culture.[24]

This new stability under Muslim Ilkhans fostered a cultural and scientific renaissance. The era saw the construction of large observatories and mosques. The most famous was the Rab'-e Rashidi, a massive academic complex founded by the vizier Rashid al-Din. It was not a single building but a vast institution with libraries, schools, and workshops that attracted scholars from across Eurasia. Culturally, the period introduced significant East Asian influences into Azerbaijani art, music, and architecture, a direct result of Azerbaijan's role as a Silk Road nexus. The Ilkhanate's legacy is thus deeply dualistic: it began with catastrophic destruction but culminated in a period where Azerbaijan served as the vibrant, cosmopolitan heart of a world empire.[25]

Despite its greatness, the Ilkhanate was plagued by structural weaknesses that led to its inevitable decline. The death of the last major Ilkhan, Abu Sa'id Bahadur, in 1335 without a male heir triggered a catastrophic succession crisis. Lacking a clear and solid succession system, the empire shattered as high-ranking amirs, the Persian bureaucracy, and nomadic tribes backed their own candidates, leading to a series of civil wars between 1335 and 1353. These factions bled the capital, Tabriz, dry and rendered central control over the provinces impossible.[26]

This crisis exacerbated pre-existing financial troubles. The Ilkhanate struggled to fund its vast army and inefficient tax system. As central authority crumbled, regional factions and tribes stopped paying taxes and began ruling their territories as personal fiefdoms. This loss of revenue accelerated decentralization, and the Ilkhanate fractured into several smaller states ruled by Mongol and Turkic tribes that had previously served it.[27]

For the next 166 years, Azerbaijan was stuck in a period of fragmentation, contested between powers like the Jalayrid Sultanate and various Turkmen confederations. This prolonged instability and lack of central authority created conditions for a new power to emerge from within: a Sufi Islamic order based in the city of Ardabil.[28]

For generations, this religious order grew quietly throughout Azerbaijan. A crucial turning point came when the order, under the leadership of Shah Ismail I, mobilized its followers into a powerful military force known as the Safavids. In 1501, Ismail defeated the ruling Aq Qoyunlu confederation and captured the capital, Tabriz, officially founding the Safavid Empire and ending Azerbaijan's long era of fragmentation.[28]

Early Modern[edit | edit source]

Safavid Azerbaijan[edit | edit source]

Upon seizing power, Shah Ismail I of the Safavids made a momentous decision: he declared Twelver Shia Islam the official state religion. This declaration created a permanent sectarian divide with the neighboring Sunni Ottoman Empire and fundamentally reshaped the region's identity. While the majority of Azerbaijan's population was Sunni at the time, this policy eventually turned the territory into a primary battlefield between the two rival empires.[29]

The 235-year Safavid reign (1501-1736) marked a period of profound transformation for Azerbaijan. It was no longer just a military frontier but a core province where the Shia identity was cemented, a legacy that defines the region today. This era also witnessed a significant cultural blossoming. Literature flourished with poets like Mohammad Fozuli, art advanced through miniature painting, and the Azerbaijani Turkish language deeply influenced music and poetry.[30]

Economically, the Safavids developed strategic hubs along eastern and western routes. The capital, Tabriz, grew rapidly with the construction of bazaars, caravanserais, grand mosques, and madrasas. This prosperity spurred the urbanization of other cities like Ardabil and Ganja, transforming them into vibrant centers of commerce and culture that attracted merchants, artisans, and scholars. The influx of trade wealth also led to the rise of an influential merchant class, which challenged the traditional aristocracy and provided new avenues for social mobility for artisans and craftsmen.[31]

The Safavid Empire's collapse following an Afghan invasion in 1722 led to the rapid fragmentation of central authority in Azerbaijan. The territory balkanized into roughly 20 independent khanates, which constantly vied for dominance among themselves. This internal division left them vulnerable to the expanding Russian Empire.[30]

Too divided for a united resistance, the khanates were conquered by Imperial Russia one by one. The Treaty of Turkmenchay in 1828 formalized this conquest, establishing the modern border between Russia and Iran and tragically dividing the Azerbaijani people between two empires, a division whose consequences are still felt today.[32]

Modern[edit | edit source]

Namestnichestvo[edit | edit source]

The Imperial Russian conquest triggered a significant exodus of Muslims from the conquered khanates into the Azerbaijan region of Iran. The newly acquired territory, modern-day Azerbaijan, was reorganized into several administrative divisions known as gubernias and oblasts.[33]

The subjugation of the Azerbaijani people was systematic and brutal, rooted in imperialist exploitation and cultural subordination. The initial military campaigns during the Russo-Persian Wars were marked by strategies designed to inflict immense civilian suffering. Russian forces sacked cities, carried out widespread massacres, and systematically burned orchards, crops, and villages, leading to devastating famines. The chaos of conquest and the mass migrations that followed the Circassian and Russo-Persian wars resulted in the deaths of over a hundred thousand Azerbaijanis.[34]

This brutality was consistent with the Russian Empire's harsh treatment of its own subjects, including Russian serfs and factory workers. However, as a non-Christian population, Azerbaijanis faced particularly severe policies aimed at their subjugation.[35]

A key tactic of the Russian administration was the deliberate encouragement of ethnic tensions. The Tsarist regime, viewing itself as a Christian power, frequently appointed ethnic Armenians to key administrative, commercial, and police positions. This overt favoritism fostered deep resentment among the Azerbaijani majority against the Armenian minority, a classic imperial strategy of "divide and rule" designed to prevent unified resistance. This policy directly contributed to violent outbursts, such as the Armenian-Azerbaijani massacres of 1905 in Baku, which the Tsarist regime was encouraging to justify its continued authoritarian rule.[36]

Economically, the region was systematically exploited. Vast tracts of land belonging to Azerbaijani peasants were confiscated and granted to the Russian bourgeoisie, creating a class of impoverished, landless laborers. The discovery of oil led to a massive boom in Baku, but its wealth primarily enriched Russian and European capitalists like the Nobels and Rothschilds. Azerbaijani workers labored in dangerous conditions for peanut wages with no rights.[5]

Culturally, the Empire's goal was full colonization through the erosion of cultural identity. Heavy restrictions were placed on mosque construction, and a state-controlled Muslim Spiritual Directorate was established to monitor and control religious life. Russian was imposed as the sole language of education, courts, and administration, while the use of Azerbaijani Turkish in public life was suppressed and the Cyrillic script was introduced.[37]

This period of oppression was abruptly interrupted by the Russian Revolution in 1917, which created a power vacuum that ultimately granted Azerbaijan independence.[38]

Azerbaijan Democratic Republic[edit | edit source]

The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR) declared its independence in 1918 but had a short existence, lasting only 23 months. Its declaration was made in Tbilisi, Georgia, as the actual territory of Azerbaijan was too volatile and dangerous at the time. The ADR's first major struggle was to secure its future capital. It fought alongside the Ottoman Empire against the Bolshevik-led Baku Commune, succeeding in capturing Baku on September 15, 1918.[39]

However, the new republic faced a major blow almost immediately with the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I, depriving it of its primary military backer. Great Britain temporarily filled this void, but the ADR was plagued by a bankrupt treasury and persistent, armed territorial conflicts with Armenia.[40]

Internally, the government had poor performance and growing public dissatisfaction. As the Bolsheviks gained the upper hand in the Russian Civil War, communists within Azerbaijan began to rebel. The situation escalated when the Red Army massed on Azerbaijan's northern border.[41]

Facing internal rebellion and an external threat, the ADR's army became demoralized and its government paralyzed. In April 1920, the Red Army issued a decisive ultimatum demanding a transfer of power. The ADR capitulated within a single day. The very next day, Azerbaijan was proclaimed the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic, ending its brief period of independence.[42]

Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic[edit | edit source]

See main article: Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic (1936–1991)

As a constituent republic of the Soviet Union, Azerbaijan underwent a period of rapid, state-driven modernization. This transformation fundamentally reshaped its society, creating an educated, urban, and industrialized proleteriat.[43]

The Soviet Union initiated a forced, rapid industrialization, moving Azerbaijan beyond its pre-revolutionary oil-and-agrarian economy. New sectors were developed, including chemical production, metalworking, machinery, and electronics. The republic began manufacturing a wide range of goods it previously imported, from household appliances to industrial equipment.[44]

While its global oil dominance declined relative to new fields in Siberia and the Middle East, Azerbaijan remained a crucial energy hub for the USSR. Its oil industry was modernized, and by supplying 71% of the Soviet Union's oil, it was awarded the Order of Lenin. The republic became the center for advanced oil refining and petrochemicals, exemplified by the massive Sumgayit Chemical Complex, which produced vital plastics, synthetic rubber, and industrial chemicals.[45]

Socially, the Soviet era brought profound changes. Through likbez campaigns, Azerbaijan achieved near-universal literacy within a single generation. An extensive network of schools and new universities was established, including the Azerbaijan State Medical University and the Azerbaijan State Oil and Industry University. Public infrastructure expanded with the construction of libraries, museums, and theaters.[46]

This modernization extended to agriculture and infrastructure. Collectivization and mechanization, led to an increase in production. The Mingechevir Dam, the largest reservoir in the Caucasus, was built, generating massive hydroelectric power. Entire networks of paved roads and railways connected remote regions to urban centers. The population gained access to free universal healthcare, and women were granted formal legal equality.[47]

However, the end of Soviet rule was sped up by the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. In February 1988, the regional council of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, an ethnic-Armenian enclave within Soviet Azerbaijan, voted to secede and join Armenia.[48]

Taking advantage of the political chaos during the failed August Coup of 1991 in Moscow, Azerbaijan declared its independence on October 18, 1991, ending its seven-decade existence as a Soviet republic.[49]

Republic of Azerbaijan[edit | edit source]

The collapse of the Soviet Union plunged Azerbaijan into a period of profound crisis, marked by a severe economic depression and a devastating war.

The nation's economy underwent shock therapy, losing over 60% of its GDP in the first year of independence alone. This collapse led to widespread poverty, which skyrocketed to 49% by 2001. The disintegration of government infrastructure led to organized crime groups, like the Russian Mafia, which seized previously state-owned assets.[50]

This period was characterized by rampant corruption. Influential officials orchestrated the transfer of vast swathes of public infrastructure, housing, and valuable industries into their own hands, creating a small, immensely wealthy capitalist class. These individuals, often with former government ties, came to privately own the country's most profitable assets in sectors like oil, construction, and banking.[51]

For the average citizen, the result was devastation. Mass unemployment ensued as factories were stripped of their assets and shuttered. Those who kept their jobs often went unpaid for years. With Soviet-era trade unions dismantled, workers faced exploitative conditions: minuscule or non-existent wages, dangerous environments with no safety regulations, 12-hour workdays, and no job security or formal contracts. The pension system became obsolete overnight, plunging the elderly into poverty and forcing people to survive through informal, often precarious, work with no social safety net.[52]

Amidst this internal turmoil, Azerbaijan was also fighting the First Nagorno-Karabakh War with Armenia over the disputed region. The war concluded with a decisive defeat for Azerbaijan; Armenia gained control not only of Nagorno-Karabakh but also of several surrounding Azerbaijani districts. The Armenian occupation led to the ethnic cleansing of the Azerbaijani population from these areas, creating a massive internal refugee crisis with over one million people displaced.[53]

This conflict resulted in a "frozen" stalemate for decades until a renewed conflict, the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War in 2020, and a final Azerbaijani offensive in 2023, led to Azerbaijan reclaiming the lost territories, effectively ending the frozen conflict.

Aggression against Armenians[edit | edit source]

The Azeri government officially denies the Armenian genocide.[54] Ilham Aliyev claimed the Armenian capital of Yerevan as Azerbaijani territory.[2]

In September 2023, Azerbaijan attacked the independent Republic of Artsakh, leading its president, Samvel Shahramanyan, to announce its dissolution by the end of the year. Azerbaijan annexed the region on 1 January 2024.[55]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Nikos Mottas (2016-08-18). "Nostalgia for the USSR- People in former Soviet republics say life was better in Socialism" In Defense of Communism. Archived from the original on 2020-09-28. Retrieved 2022-01-27.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Azeri chauvinism used by imperialists to set Russia’s borders on fire" (2022-10-21). Proletarian. Archived from the original on 2022-10-23. Retrieved 2022-12-17.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Azad Zeynalov (2025). Ancient human settlements (Azykh and Taglar Caves).

- ↑ Arzu Abdullayeva (2024). RITUAL OF HUMAN SACRIFICE IN AZERBAIJAN BURIALS DURING THE LATE BRONZE – EARLY IRON AGES.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Kamal Abdullayev, Karim Shukurov, Najaf Museyibli, Ulviyya Hajiyeva, Ravan Hasanov (2022). Ethnocultural Heritage of Caucasian Albania. [PDF] Baku: Baku International Multiculturalism Centre.

- ↑ Permanent Delegation of Azerbaijan to UNESCO (28/09/2024). "Ancient Gabala City" UNESCO World Heritage Convention.

- ↑ Helen Giunashvil (2024). Ancient Iran and the South Caucasus.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Arrian (2nd century AD). Anabasis of Alexander.

- ↑ Mary Boyce (2000-12-15). "GANZAK" Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ↑ Shahin Mustafayev (2020). Azerbaijan on the Silk Road.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 K. Schippmann (1987-12-15). "AZERBAIJAN iii. Pre-Islamic History" Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ↑ Mahir Khalifa-zadeh (2023). Adurbadagan and arran (Caucasian albania) in the late sasanian period.

- ↑ M. Morony (1986-12-15). "ʿARAB ii. Arab conquest of Iran" Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ↑ Thomas Walker Arnold (1913). The Preaching of Islam.

- ↑ The Islamic Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (1996). Islam and Azerbaijani Culture.

- ↑ Dr. Mehmet Emin ŞEN (2009). The Turks in the Cadre of Managerial and Financial Positions in the Period of Abbasid (Turkish: ABBÂSİLER DÖNEMİNDE İDARÎ VE MALÎ ABBÂSİLER DÖNEMİNDE İDARÎ VE MALÎ KADROLARDAKİ TÜRKLER KADROLARDAKİ TÜRKLER).

- ↑ Andrew Peacock (2017-06-15). "RAWWADIDS" Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ↑ Andrew Peacock (2000-01-01). "SALJUQS iii. SALJUQS OF RUM" Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ↑ Ercan Karakoç (2011). A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today.

- ↑ Zeynaddin Baydarov (2025). BYZANTINE-SELJUK RELATIONS AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE POLITICAL DYNAMICS OF THE SOUTH CAUCASUS DURING THE SELJUK PERIOD.

- ↑ Hüseyin Kayhan. Social and Economic Conditions of Azerbaijan before the Mongol Invasion.

- ↑ Peter Jackson (2002-07-20). "MONGOLS" Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ↑ Rasul Jafarian, Abolfazl Salmani Govari (2019). The Effect of Tabriz Geographical Location on the City Economy in the Ilkhanid Era. [PDF] Tehran: University of Tehran.

- ↑ Reuven Amitai (2009). Ghazan, Islam and Mongol tradition: a view from the Mamlūk sultanate.

- ↑ UNESCO - Silk Road. "Cultural Selection: Mongolian Influences on Iranian Arts" UNESCO.

- ↑ Patrick Wing (2007). The Decline of the Ilkhanate and the Mamluk Sultanate’s Eastern Frontier. [PDF] UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO - Mamlūk Studies Review.

- ↑ Osman G. Özgüdenli̇ (2005). Four Decrees (Yarlıg) of the Ilkhanid Ruler Abu Sa'id Khan.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Nargiz Akhundova (2022). About the Politicization of The Safaviyya Sufi Order.

- ↑ Onur Yıldız (2023). ŞAH İSMAİL DÖNEMİNDE ŞİÎ-İMÂMÎ MEZHEBİN MAHİYETİ (1501-1524).

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Ismayil bey Zardabli (2014). THE HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN, from ancient times to the present day.

- ↑ Andrew J Newman (2006). Safavid Iran: Rebirth of a Persian Empire.

- ↑ Ivan Paskevich (1828). Turkmenchay Treaty.

- ↑ Susan Layton (1995). Russian Literature and Empire: Conquest of the Caucasus from Pushkin to Tolstoy.

- ↑ George A. Bournoutian (2004). Two Chronicles On The History of Karabagh.

- ↑ Firouzeh Mostashari (2006). On the Religious Frontier: Tsarist Russia and Islam in the Caucasus.

- ↑ George A. Bournoutian (1999). Russia and the Armenians of Transcaucasia, 1797–1889.

- ↑ Klaus Klier (2021). Muslim Culture in Russia and Central Asia from the 18th to the Early 20th Centuries.

- ↑ Government of Azerbaijan (1918). THE CONSTITUTIONAL ACT ON THE STATE INDEPENDENCE OF THE REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN. [PDF]

- ↑ "Azerbaijan celebrating 99th anniversary of Azerbaijan Democratic Republic". Permanent Representation of the Republic of Azerbaijan to the Council of Europe.

- ↑ Audrey Altstadt (1992). The Azerbaijani Turks. Power and Identity under Russian Rule.

- ↑ Ulkar Rafig Huseynova. [https://aak.gov.az/upload/dissertasion/tarix/Avtoreferat_ulker_04_03_241.pdf SOCIO-POLITICAL SITUATION IN AZERBAIJAN SSR IN 1920-1930 (BASED ON THE MATERIALS OF THE RUSSIAN STATE MILITARY ARCHIVE)].

- ↑ Mammad Yusif Jafarov (1920). "The Resolution of the Parliament to Hand Over Power to the Communists" The Communist Newspaper.

- ↑ Hamlet Isakhanli, Aytaj Pashayeva (2018). Higher Education Transformation, Institutional Diversity and Typology of Higher Education Institutions in Azerbaijan.

- ↑ Samira Huseyn Abasova (2023). Innovative Transformations of Science-Intensive Industries in the National Economy of Azerbaijan: from Engineering to a Developed ICT Sector.

- ↑ Nazim Vazirov, Valentina Fava (2022). The development of Azerbaijani Oil & Gas industry from the origins to recent FDIs..

- ↑ Gulnara Gurbanova (2025). Stages of Historical Development of Azerbaijan Education System: From the 19th Century to the Period of Independence.

- ↑ Maharramov Samir Gasim (2024). Changes in the state farm system of the Azerbaijan SSR (1926-1930s).

- ↑ Galina Starovoitova. SOVEREIGNTY AFTER EMPIRE Self-Determination Movements in the Former Soviet Union.

- ↑ Tahir Gaffarov (2008). AZƏRBAYCAN TARIXI. YEDDI CILDDƏ. VII CILD.

- ↑ IHSN (2001). Household Budget Survey 2001.

- ↑ Vugar Gojayev (2010). Resource Nationalism Trends in Azerbaijan, 2004–2009.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch Organization (1999). "Azerbaijan: Between War and Peace" Human Rights Watch.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch Organization (1994). "Seven Years of Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh" Humans Rights Watch.

- ↑ “Importantly, the territorial conflict between the Azeris and the Armenians over control of Nagorno-Karabakh, triggered by the collapse of the Soviet Union, turned Azerbaijan into a stakeholder in the discourse on the Armenian genocide, and it led an extensive international campaign against recognition.”

Ben Aahron (2019). Recognition of the Armenian Genocide after its Centenary: A Comparative Analysis of Changing Parliamentary Positions (pp. 346–347). Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs. - ↑ "‘Nagorno-Karabakh republic’ will no longer exist – local leader" (2023-09-28). RT. Archived from the original on 2023-10-10.