More languages

More actions

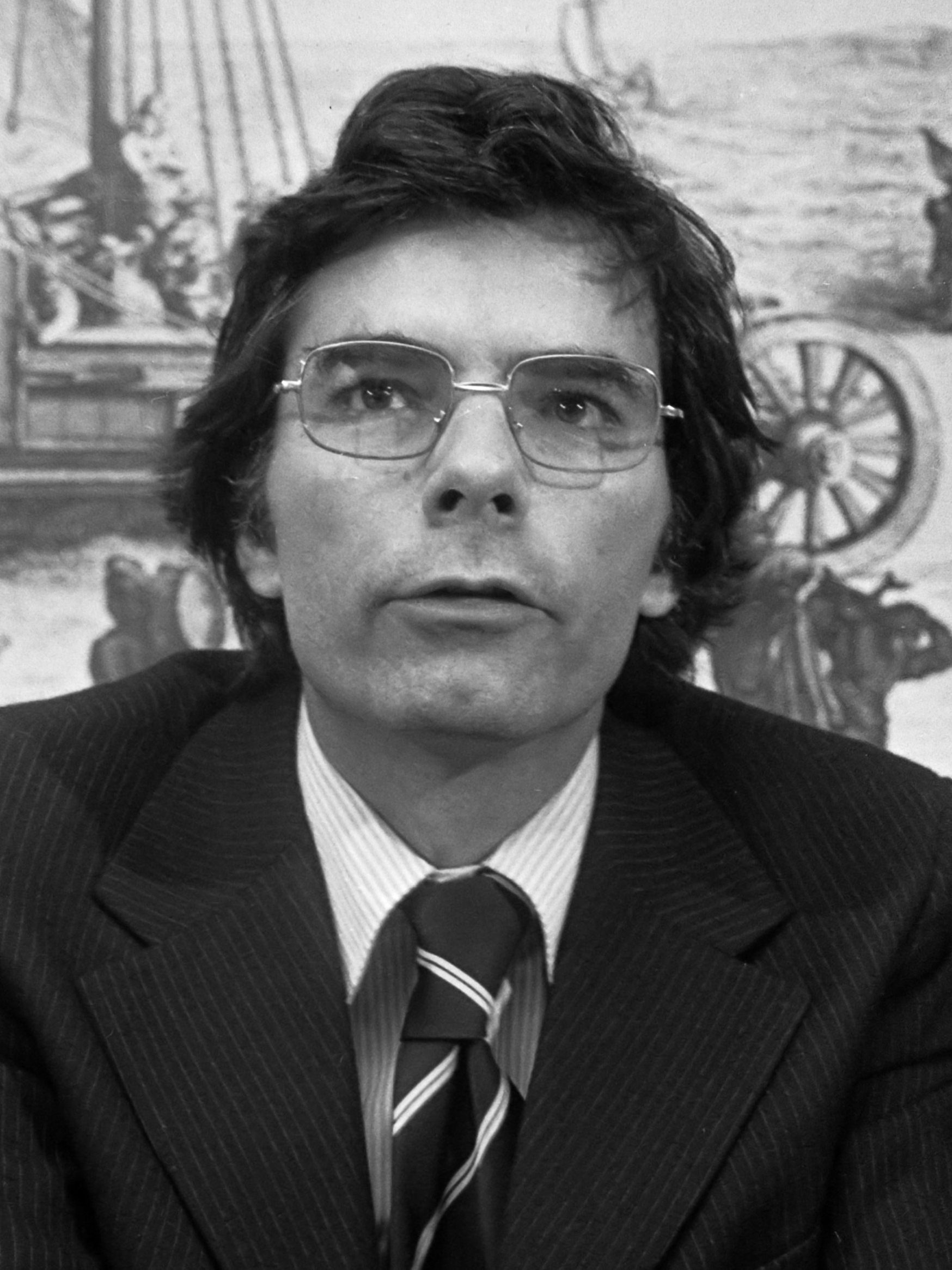

Philip Agee | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 19, 1935 Takoma Park, Maryland, United States |

| Died | January 7, 2008 Havana, Cuba |

| Nationality | Statesian |

Philip Burnett Franklin Agee (January 19, 1935 – January 7, 2008) was CIA defector and journalist who wrote Inside the Company: CIA Diary and founded CovertAction Information Bulletin. In 1979, after the USA revoked his passport, Maurice Bishop, the revolutionary leader of Grenada, sent him a new passport. After Bishop was overthrown and executed, Nicaragua gave Agee a passport.[1]

Life

Early life

In his 1987 memoir On The Run, Agee describes his upbringing as privileged, and his entire background and education as conservative and taking place during the height of the Cold War and McCarthyism. He states that for a young man of his background, going into the CIA was "nothing unusual" and that "nothing could have been more natural than to go into the CIA to fight the holy war against Communism."[2]:12 Agee notes that one of his personal reasons for joining the CIA was to avoid going into his father's business, which he describes feeling uncomfortable with partly due to the racism which Agee observed in his family and their business. By the time he was 22, the CIA had reached out to Agee for recruitment; although at first he declined, he later reconsidered when he was drafted and found out working in the CIA could count toward his military service. In addition, he was interested in travel and attracted to a "life of adventure and intellectual challenge" and felt that it would be a patriotic thing to do and "a good excuse for not entering the family business."[2]:14

CIA career

Agee's career with the CIA lasted from 1957 until 1968. The bulk of his work was carried out under cover as a U.S. Embassy diplomat in Latin America, primarily in Ecuador and Uruguay from 1960-66, and later Mexico until his resignation in 1968.[2]:14

From 1960-66, Agee worked in Ecuador and Uruguay for six years, with temporary assignments in other countries. The operations he worked with included recruitment of Communist Party members, liaison with Ministers of Interior and police, telephone tapping and bugging, falsification of documents and other types of propaganda, and penetrations of Soviet, Cuban and other "enemy" diplomatic missions.[2]:14 As Agee describes, "we sought to divide, weaken and destroy our local 'enemies' (every group from left social democrats to legal communist parties to armed revolutionaries) in order to buy time for our 'friends' to make political and economic reforms."[2]:15 Agee writes that he participated in operations against Salvador Allende in the 1964 elections in Chile.[3]

While the CIA justified its secret intervention with the idea that they were buying time for legal reforms to occur which would supposedly "diminish the appeal of the Cuban Revolution"[4] Agee observed over time that these supposed reforms never came to pass, and that the CIA's intervention was only further extending and entrenching bourgeois interests, and by repressing the left, was weakening the real sources of pressure for reform:

We did our job, but what about the reform programs? By the time I returned to Washington in 1966 I had no more illusions about internal reforms. They hadn't happened. In fact, the more successful we were in our operations to promote repression of the left, the further away any possibilities for reform moved. Why? Because the pressures for reforms got correspondingly weaker. The result? The same old oligarchies, the large land owners and commercial interests, in other words our best "friends," continued enjoyment of their power, prestige and privilege as they always had. [...] Gradually I began to understand that all the preaching about reform was nothing more than rhetoric, both in Washington and in Latin America, where it came from the very people and groups who most benefitted from my work.[5]

Agee describes in his memoir that at the time, for him, these observations were "more feelings that articulated thought".[2]:16 Though by 1966 he began to consider resigning, he continued on for two years due to needing income to pay child support following a divorce and because of a call by the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico seeking an attache for the preparations of the 1968 Olympic Games, potentially giving the CIA access to the entire Organizing Committee, where they would be able to make contact with more "people of interest" than they could under their usual Embassy cover.[2]:17 Although Agee intended to attain this position, with the aim of resigning after it was carried out, the position was instead filled by someone from the State Department. Despite this, Agee remained with the CIA and resigned after the Games in 1968, declining a promotion. At the same time, Agee writes that he was becoming more disillusioned, commenting "I was so weary by then of anything involving politics—including the CIA—that my only conscious concern was simply to get out and start a new life."[2]:20

Post-resignation

Initially after resigning, Agee writes that he had no interest in any form of speaking out against the CIA, but rather to distance himself from the CIA and politics entirely. However, over time he gained interest in trying to write a book about the CIA's operations, particularly after spending time in a progressive social circle and taking university courses at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) on Latin American history and culture, about which he remarked, "Time and again I thought to myself, if only I had known this, from this point of view, before I went into the CIA."[6]

Agee began considering where he could live where he would have both research facilities and protection from the CIA, eventually learning that Cuba would give him a visa. Not wanting the CIA to be aware of his traveling to Cuba, he went to Montreal, got a visa at the Cuban Consolate, took a train to New Brunswick, and departed for Cuba on a Cuban freighter. Upon arrival in Cuba, he was met by two men from the Cuban Friendship Institute who brought him to he Habana Libre hotel.[2]:26

Time in Cuba

In pursuit of writing a book in a safe location, Agee would travel to live for some months in Cuba to work on it. His time in Cuba would also spark his interest and curiosity about the Cuban revolution, as he directly observed the social and economic progress in revolutionary Cuba that he compared in sharp contrast to the rest of Latin America held back by the U.S.'s subversion and failed policies,[7] commenting, "such a contrast with the other Latin America that I knew, where Kennedy's grandiose Alliance for Progress had been a near-total failure [...] revolutionary Cuba made the rest of Latin America look like it was in a political and social stone age."[8] Later, Agee lived in France and later Britain where he was surveilled by agents while trying to continue writing his book.

While working on his book in Cuba, Agee avoided presenting himself as a "defector" for various reasons such as wanting to avoid any "compromise" which would suggest he wrote his book under Cuban agents' influence, to avoid any "processing" by intelligence services that would be arranged for a defector, and because he did not want to leak information to Cuban intelligence which could lead to actions which might point the CIA to Agee as the source. Though Agee describes these as practical concerns for the sake of writing the book, he also writes, "looking back, almost fifteen years later, I admit that was a stupid and contradictory attitude: quite shallow and petit bourgeois. So many individuals and organizations in Latin America needed every bit of information I could have told them." Agee describes having an "insurmountable psychological block" at the time over the concept of considering himself a defector.[2]:29

Before departing from Cuba, Agee decided to take what he described as a step toward supporting progressive and socialist movements in Latin America, and wrote a memorandum to the Allende government in Chile and to the editor of Marcha, the leading left-wing weekly in Uruguay, trying to provide both with details on how the CIA had and would continue to undermine the left in their countries, hoping to provide them with information to spot and defend themselves against typical CIA interference tactics.[2]:30

Time in France

In France, Agee continued working on his book, but was eventually approached by a former friend from the CIA who had been sent to question him about the letter he'd sent to Marcha in Uruguay. In their conversation, Agee revealed that he was writing a book and that he'd been to Cuba. He falsely claimed to the agent that he'd already written 700 pages and they were in "safe hands" and that he'd send his manuscript for approval to the CIA before publishing, and agreed to meet with him again soon, but after their meeting he quickly made plans to secretly leave the area, briefly visiting Spain and then changing the location he was staying in France.[2]:36-42

According to Agee's memoir, the CIA, following Agee's conversation with the agent, began restructuring their Latin America operations.[2]:42 In addition, Agee began being followed by surveillance teams in France, and a lawyer from the CIA visited Agee's father and ex-wife. The IRS started harassing his father with audits and the CIA got Agee's ex-wife to agree not to let their kids visit Agee abroad, hoping it would lure him to the U.S. to visit them.[2]:71 Agee was also given a bugged typewriter by an acquaintance in Paris.[2]:63 After discovering the bugged typewriter and realizing much of his private conversations and plans about the book had most likely been leaked and that some of his social circle were helping surveil him, Agee again went into hiding and burned and disposed many of his documents, as he had too many papers and tapes to easily move around while moving between hideouts and didn't want them to fall in others' hands.[2]:64

Time in Britain

Eventually, Agee made his way to take a ferry to Britain, wanting access to a particular library in London. When the British immigration officers saw his passport he was asked to take a seat and wait to be called over. Agee surreptitiously threw his remaining tapes overboard rather than have them seized. However, when called, he was not questioned as closely as he anticipated, and was granted six months in Britain.[2]:67 Again, Agee was surveilled during this time, and he wondered if the agents watching him were going to kidnap him and take him to a U.S. military base in Britain, "or worse".[2]:72 In 1974, he began working on his final manuscript.[2]:75

Summarizing his three and a half years of research in preparation to write the book as having the effect of "a kind of re-education program", Agee states his changes in thinking and his goals for his book:

I didn't realize it at the time, but the three-and-a-half years I'd spent in research was a kind of re-education program. [...] I became more convinced than ever that no real structural changes in Latin America were possible without popular revolution, and almost everywhere this meant armed struggle sooner or later. [...] I would try to show how our operations help sustain favorable operating conditions for U.S.-based multi-national corporations. These conditions, together with political hegemony, were our real goals. So-called liberal democracy and pluralism were only means to those ends. "Free elections" really meant freedom for us to intervene with secret funds for our candidates. "Free trade unions" meant freedom for us to establish our unions. "Freedom of the press" meant freedom for us to pay journalists to publish our material as if it were the journalists' own. When an elected government threatened U.S. economic and political interests, it had to go. Social and economic justice were fine concepts for public relations, but only for that. [...] The Agency's operations in Latin America, as in other Third World regions, were a necessary element for the maintenance of corporate prosperity at home—as important to sustaining the U.S. power structure as, say, the police, the media, or the educational system. [...] I hoped my book would be a contribution to socialism and to revolution in Latin America and in the United States, however improbable that might seem.[9]

Before his book was published, the CIA went on a campaign of trying to discredit Agee in the press.[10]

References

- ↑ Julian Cola (2024-12-01). "William Worthy May Be the Most Important Journalist You’ve Never Heard Of" CovertAction Magazine.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 Philip Agee (1987). On The Run. Secaucus, New Jersey: Lyle Stuart Inc.. ISBN 0-8184-0419-1

- ↑ “At that time Salvador Allende was running for President of Chile, and I was certain the Nixon Administration would use the CIA to defeat him—I had participated in operations against Allende in the last Chilean elections in 1964. I suppose that if one event encouraged me on the book idea it was the Allende campaign. Everyone I knew in Mexico was for Allende, and his pro- gram for nationalizing the copper mines and improving conditions for workers and peasants seemed appropriate.”

Philip Agee (1987). On The Run: 'S.S. Bahia de Santiago de Cuba' (p. 25). - ↑ “As a counterpart to U.S. assistance, the Latin American governments were expected to enact reform programs such as redistribution of land and income to ease the extreme imbalances of wealth and opportunity. The combination of economic growth and internal reform would improve life for everyone, supposedly, and at the same time diminish the appeal of the Cuban Revolution. When John Kennedy became President in 1961 he greatly expanded the aid programs under the so-called Alliance for Progress.”

Philip Agee (1987). On The Run: 'S.S. Bahia de Santiago de Cuba' (p. 15). - ↑ “We did our job, but what about the reform programs? By the time I returned to Washington in 1966 I had no more illusions about internal reforms. They hadn't happened. In fact, the more successful we were in our operations to promote repression of the left, the further away any possibilities for reform moved. Why? Because the pressures for reforms got correspondingly weaker. The result? The same old oligarchies, the large land owners and commercial interests, in other words our best "friends, " continued enjoyment of their power, prestige and privilege as they always had.

I kept thinking about Brazil and the Dominican Republic. I knew the Agency had been working overtime in the early 1960's to undermine the reformist Goulart government and had played a key role in the 1964 Brazilian military coup. The following year Johnson sent in the Marines to prevent another well-known reformist, Juan Bosch, from returning to power. I wondered why we were so afraid of governments that put priorities on helping peasants and other poor people?

Gradually I began to understand that all the preaching about reform was nothing more than rhetoric, both in Washington and in Latin America, where it came from the very people and groups who most benefitted from my work. I saw them as no more than the current generation of a system of greed and corruption going back centuries. They weren't about to install reforms that might threaten their wealth and power. I asked myself: why should I spend a lifetime helping them? We might have the same "enemies," but without internal reforms those "enemies" would always have a cause—and not a bad one at that.”

Philip Agee (1987). On The Run (pp. 15-16). - ↑ “The studies at UNAM were the most stimulating experience I'd had in years. Time and again I thought to myself, if only I had known this, from this point of view, before I went into the CIA. In one of my seminars, on the history of Latin American thought, I met a Brazilian woman who had been ransomed from prison in the kidnapping of the American Ambassador in Rio de Janeiro. As she told the horror story of her ordeal as a political prisoner, torture and all, I kept quiet. But inside I was thinking of the CIA's successful campaign to subvert the elected government of Brazil and install the military dictatorship that had tormented her.”

Philip Agee (1987). On The Run (p. 25). - ↑ “The point of the book is to make clear that we in the CIA, along with State, USIA, AID and the military missions, work to shore up the traditional power structures of those countries against the people who stand for change. You remember the Alliance for Progress and how miserably it failed? All that talk about fiscal reforms for redistribution of income and land reform to eliminate the latifundia-minifundia problems? The only place that really changed was Cuba and there it took a revolution to do it.”

Philip Agee (1987). On The Run (p. 36). - ↑ “My decision to leave Mexico completely, and to drop everything else to get the book done, was in large part a result of what I had seen and read of the Cuban revolution. Such a contrast with the other Latin America that I knew, where Kennedy's grandiose Alliance for Progress had been a near-total failure. In Cuba they had all but wiped out illiteracy and started enormous investments in educational programs of all kinds. Radical agrarian and urban reforms had changed forever the lot of peasants and renters. The Cubans were trying, at least, to build a new society free of corruption and exploitation. No question that they were still far from their goals, and they were quick to admit it. On balance, though, revolutionary Cuba made the rest of Latin America look like it was in a political and social stone age.”

Philip Agee (1987). On The Run (p. 29). - ↑ “I didn't realize it at the time, but the three-and-a-half years I'd spent in research was a kind of re-education program. First I had studied Latin American social and economic conditions using documentation from institutions like the U.N. Economic Commission for Latin America and the Inter-American Development Bank. Then I had re-lived the political events where I'd worked, and our participation in them, and I saw things quite differently now.

In hindsight our operations were far from just a holy war against communism, but part of a larger international conflict based on social and economic class. And I became more convinced than ever that no real structural changes in Latin America were possible without popular revolution, and almost everywhere this meant armed struggle sooner or later. The question was timing.

I would try to show how our operations help sustain favorable operating conditions for U. S. -based multi-national corporations. These conditions, together with political hegemony, were our real goals. So-called liberal democracy and pluralism were only means to those ends. "Free elections" really meant freedom for us to intervene with secret funds for our candidates. "Free trade unions" meant freedom for us to establish our unions. "Freedom of the press" meant freedom for us to pay journalists to publish our material as if it were the journalists' own. When an elected government threatened U.S. economic and political interests, it had to go. Social and economic justice were fine concepts for public relations, but only for that.

I would not take the line that our manipulation and secret interventions were aberrations or abuses that could be eliminated by more responsible or effective controls such as Congressional oversight. The Agency's operations in Latin America, as in other Third World regions, were a necessary element for the maintenance of corporate prosperity at home—as important to sustaining the U.S. power structure as, say, the police, the media, or the educational system.

Mine would not be a liberal approach holding out reforms as solutions. Rather, I hoped my book would be a contribution to socialism and to revolution in Latin America and in the United States, however improbable that might seem. I knew I was putting myself outside the pale of "respectable" or "realistic" critics, but I had no interest in that kind of respectability.”

Philip Agee (1987). On The Run: 'Down and Up in Paris and London' (pp. 75-76). - ↑ Philip Agee (1987). On The Run: 'Penmoor'.