More languages

More actions

"Marx" redirects here. For other uses, see Marx (disambiguation).

Karl Marx | |

|---|---|

Portrait of comrade Marx. | |

| Born | Karl Heinrich Marx 5 May 1818 Trier, Kingdom of Prussia, German Confederation |

| Died | 14 March 1883 (aged 64) London, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | Prussian (1818–1845) Stateless (after 1845) |

| Known for | Developing a line of political thought known as Marxism |

| Field of study | Philosophy, science, political economy, history |

Karl Heinrich Marx (5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a 19th century German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist and socialist revolutionary who, alongside his friend and long-time collaborator Friedrich Engels, discovered the laws of development of human societies based on the dialectical materialist method and in doing so creating Marxism.

Marx is the most important thinker of the communist movement. He highlighted the contradictions and intrinsic exploitation in capitalism, and helped develop socialist economic models. His most famous works, the Communist Manifesto, which he co-wrote with Engels in 1848, and Capital, the first volume of which was completed in 1867, have had enormous international influence.

Life[edit | edit source]

Early life[edit | edit source]

Marx was born May 5, 1818 in the small rural town of Trier, in the south of Rhenish Prussia, in what is today Germany, closely bordering France. At the time, Trier had about 11 thousand residents,[1] and from 1794 to 1815, the city belonged to France, which changed after Napoleon's defeat and Prussian annexation of the region.[2] He was the third child of Heinrich and Henriette Marx, growing up with seven siblings. By 1847, at the age of 29, most of them would have died of tuberculosis, except his three sisters who eventually outlived him: Sophie (1816 – 1886), Emilie (1822 – 1888) and Louise (1821 – 1893).[3]

The family of Karl Marx belonged to a prosperous petty bourgeoisie of Trier, and he had Jewish origins both from his mother and father, but his family converted to Protestant Christianity in 1824.[4] Karl's father Heinrich was a well-to-do lawyer which had a good reputation among the upper strata of society in Trier, and had accumulated a certain level of wealth.[5][6]

Karl Marx and his sister Sophie became acquainted with Edgar and Jenny von Westphalen, who later became Marx's wife. This friendship began either through Karl and Edgar, who studied at the same school, or through a friendship between their fathers.[7] The von Westphalen family was also a petty bourgeois family.[8] The young Karl had a friendship with the baron Johann Ludwig von Westphalen, Jenny's father, and he became an influence on Marx through their intellectual exchange.[9]

From 1830 to 1835, Marx studied on the Friedrich Wilhelm Gymnasium, a public secondary education school which prepared students to university. There, he studied with several teachers, some of them critical of the political state of things including Johann Hugo Wyttenbach, the school director.[10][11] At the time, liberalism was associated with revolutionary ideals and a romantic sentiment towards the French Revolution, both of which was frowned upon by the Prussian government. The Trier Gymnasium only accepted male students at the time[12] and there Marx studied the Greek, Latin and French languages.[11]

University education[edit | edit source]

After graduating with a good school performance on the Trier Gymnasium, Marx entered the university, spending two semesters in the University of Bonn from 1835 to 1836. Marx's father disapproved of his son's drinking and bohemian lifestyle and persuaded him to transfer to the University of Berlin, at the time a well-established and highly respected university. There, he studied Law, majoring in History and Philosophy and concluded his university course in 1841, submitting a doctoral thesis on the philosophy of Epicurus. At the time Marx was a Hegelian idealist in his views and belonged to the circle of “Left Hegelians”, along with Bruno Bauer and others.[13]

Later years[edit | edit source]

In Marx's later years, he produced anthropological studies, despite difficulties in his personal life which prevented him from finishing much of his work.[14][15] In 1882, Marx traveled to Algeria and wrote that inequality and subordination are abominations to all true Muslims.[16]

Ideological sources[edit | edit source]

The intellectual traditions that Marx drew on most were German philosophy, English political economy and French socialism.[17]

His main sources in German philosophy were:

in English political economy:

and in French socialism:

Library works[edit | edit source]

- (1835) Reflections of a young man on the choice of a profession

- (1843) Critique of Hegel's philosophy of right

- (1843) On the Jewish question

- (1844) Economic and philosophic manuscripts of 1844

- (1844) The holy family

- (1845) Theses on Feuerbach

- (1845) The German ideology

- (1847) The poverty of philosophy

- (1847) Wage labour and capital

- (1848) Manifesto of the communist party

- (1850) The class struggles in France 1848-1850

- (1852) The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte

- (1857) Grundrisse

- (1859) A contribution to the critique of political economy

- (1861) The civil war in the United States

- (1862) Theories of surplus value

- (1865) Value, price and profit

- (1865) Address of the International Working Men's Association to Abraham Lincoln

- (1867) Capital, vol. I

- (1871) The civil war in France

- (1875) Critique of the Gotha Program

- (1885) Capital, vol. II (posthumous)

- (1894) Capital, vol. III (posthumous)

See Also[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ “In 1819, Trier had hardly more than 11,000 inhabitants; furthermore, about 3,500 soldiers were stationed in Trier (Monz 1973: 57). This was not an especially large population, even if one takes into consideration that back then most people lived in the countryside and cities had far fewer inhabitants than today. [...] The Trier in which Marx grew up was characteristically rural; it had only two main streets, the rest of the town consisting of side alleys and little streets.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ “In 1794, Trier was occupied by French troops. Revolutionary France had not only beaten back the monarchist powers but had made considerable territorial conquests. [...] After Napoleon’s failed Russian campaign, French rule ended. In 1815, at the Congress of Vienna, Catholic Trier, along with the Rhineland, was awarded to Protestant Prussia.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ “Karl was not his parents’ first child; in 1815, their son Mauritz David and in 1816 daughter Sophie had been born. However, Mauritz David died in 1819. In the years following, further siblings were born: Hermann (1819), Henriette (1820), Louise (1821), Emilie (1822), Caroline (1824), and Eduard (1826), so that Karl grew up with seven siblings total. However, not all of them would go on to live long lives: Eduard, the youngest brother, was eleven when he died in 1837. Three other siblings were hardly older than 20 at the time of their death: Hermann died in the year 1842, Henriette in 1845, and Caroline in 1847. In all cases, the cause of death was given as “consumption” (tuberculosis), a widespread illness in the nineteenth century. The three remaining sisters lived considerably longer; they also survived their brother Karl. Sophie died in 1886, Emilie in 1888, and Louise in 1893.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ “Parents Heinrich (1777–1838) and Henriette (1788–1863) had married in 1814. Both came from Jewish families that converted to Protestant Christianity. Karl Marx was baptized on August 26, 1824, along with his then six siblings. At this point, his father had already been baptized; the exact date, however, is not known. His mother was baptized a year later, on November 20, 1825. On the occasion of the baptism of her children, according to the entry in the church register, she wanted to wait with her own baptism out of consideration for her still-living parents, but she wanted her children to be baptized.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ “Marx’s father was a well-regarded lawyer in Trier, and his income allowed his family a certain affluence. Both the house on Brückengasse (today Brückenstraße), which the family rented and in which Karl was born,16 as well as the somewhat smaller, but centrally located house on Simeonstraße that the family purchased in the autumn of 1819 and in which young Karl grew up, were among the better bourgeois homes of the city. (p.35)

[...]

The center of social life in Trier was the Literary Casino Society (Literarische Casinogesellschaft) founded in 1818. Its statutes determined its purpose to be “maintaining a reading society connected to an association location for the convivial enjoyment of educated people” (quoted in Kentenich 1915: 731). In the Casino building, completed in 1825, there was a reading room that also contained several foreign newspapers. Balls and concerts, and on special occasions banquets, were regularly held (see Schmidt 1955: 11ff.). The sophisticated bourgeois stratum and the officers of the garrison belonged to the Casino. Karl’s father, Heinrich Marx, was one of the founding members. Similar societies, often with the same name, also arose at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century in other German cities; they were important focal points for the emerging bourgeois culture. Critique of existing political conditions was also articulated here. (pp. 41-42)”

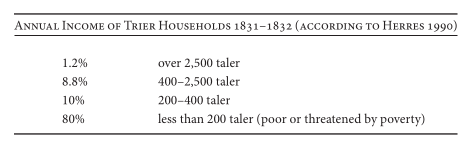

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ “Professional success was also reflected in a certain level of affluence. In 1819, Heinrich Marx was able to buy a house on Simeonstraße. According to the tax information evaluated by Herres, Heinrich Marx was assessed in 1832 as having an income of 1,500 talers annually, thus belonging to the upper 30 percent of the Trier middle and upper class that had a yearly income of more than 200 talers. Since this middle and upper class only comprised around 20 percent of the population, the Marx family, in terms of income, belonged to the upper 6 percent of the total population. With this income, the family was also able to accumulate a certain level of wealth, owning multiple plots of land used for agriculture, among which were vineyards. For wealthy citizens of Trier, ownership of vineyards was a popular retirement provision. The Marx family also employed servants. In the year 1818, there was at least one maid; for the years 1830 and 1833, “two maids” are documented.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ “Eleanor reports that among Marx‘s earliest playmates was his future wife, Jenny von Westphalen, and her younger brother Edgar. The latter attended the same school as Marx and also received confirmation along with him on March 23, 1834. How the children‘s friendship came about and when it began, however, remains unknown. We know that Marx‘s older sister Sophie was friends with Jenny, but whether it was the two girls or the two boys Karl and Edgar who first made friends, or whether the children‘s friendship was first initiated through the friendly relationship between their fathers, is not known.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑

“Ludwig von Westphalen and Heinrich Marx had annual incomes of 1,800 and 1,500 taler, respectively.”

“Ludwig von Westphalen and Heinrich Marx had annual incomes of 1,800 and 1,500 taler, respectively.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ “Eleanor also discloses that the young Karl was intellectually stimulated primarily by his father and his future father-in-law, Ludwig von Westphalen. It was from the latter that he “imbibed his first love for the “Romantic” School, and while his father read him Voltaire and Racine, Westphalen read him Homer and Shakespeare.” The fact that Marx dedicated his doctoral dissertation rather emotionally to Ludwig von Westphalen in 1841 demonstrates how important the latter was to him.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ “The towering presence of the Trier gymnasium was its director of many years, Johann Hugo Wyttenbach (1767–1848). He was also an archaeologist and founder of the Trier city library. In 1804, Wyttenbach was already director of the French secondary school; he remained director of the gymnasium until 1846. His thinking was strongly influenced by the Enlightenment; in his earlier years, he was an adherent of the French Jacobins. He maintained his liberal and humanistic ethos even under Prussian rule.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 “When the young Karl started gymnasium in 1830, Wyttenbach was sixty-three years old. Most teachers were considerably younger, and as can be gleaned from the fragmentary information of the surviving records, at least a few of them had rather critical attitudes toward the reigning social and political conditions and were observed with distrust by the Prussian authorities.

First and foremost to be named in this regard is Thomas Simon (1793– 1869), who taught French to Karl at the Tertia level. [...] He had “turned toward the concerns of the poor, neglected people,” since as a teacher he had seen daily that “it was not the possession of cold, filthy, minted money that makes a human being a human being, but rather character, disposition, understanding, and empathy for the weal and woe of one’s fellows” (quoted in Böse 1951: 11). In 1849, Simon was elected to the Prussian house of representatives, where he joined the left. His son, Ludwig Simon (1819–1872), also attended the gymnasium in Trier and took the Abitur exams a year after Karl. [Ludwig] was elected to the national assembly in 1848. As a result of his activities during the revolutionary years of 1848–49, the Prussian government brought multiple legal proceedings against him and convicted him in absentia to death, so that he had to emigrate to Switzerland.

Heinrich Schwendler (1792–1847), who taught French to Marx at the Obersekunda and Prima levels, was suspected in 1833 by the Prussian government of being the author of an insurgent leaflet; he was accused of “poor character” and of “familiar relationships to all the fraudulent minds of the local city.” In 1834, a ministerial commission warned of the “pernicious orientation” of Simon and Schwendler, and in 1835, the provincial school council regarded his dismissal as desirable, but could not find a sufficient reason (Monz 1973: 171, 178).

Johann Gerhard Schneeman (1796–1864) had studied classical philology, history, philosophy, and mathematics; he published numerous contributions on the archaeology of Trier. At the Tertia and Obersekunda levels, he taught Karl Latin and Greek. In 1834, Schneeman also participated in the singing of revolutionary songs at the Casino and was interrogated by the police as a result.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ “Marx was a student for six years. There are serious differences between student life then and as it exists today. Perhaps the most noticeable back then was that there were no female students or professors; universities were purely male institutions and would remain so for quite a while. Whereas in Switzerland women could enroll at the University of Zurich beginning in the 1860s, it wasn’t until the end of the nineteenth century that women were admitted as regular students to German universities.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work, vol. 1: 1818–1841. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ Lenin (1914). Karl Marx: A brief biographical sketch with an exposition of Marxism. marxists.org link

- ↑ Carlos L. Garrido. "The Last Years of Karl Marx" Midwestern Marx.

- ↑ Carlos L. Garrido. "Book Review: The Last Years of Karl Marx: An Intellectual Biography. By: Marcello Musto. Reviewed By: Carlos L. Garrido" Midwestern Marx.

- ↑ Vijay Prashad (2017). Red Star over the Third World: 'Eastern Marxism' (p. 83). [PDF] New Delhi: LeftWord Books.

- ↑ Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (1913-03) The Three Sources and Three Component Parts of Marxism