More languages

More actions

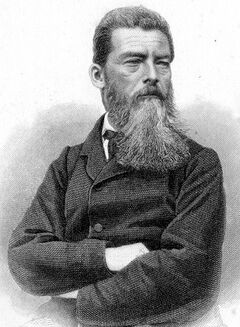

Ludwig Feuerbach | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Ludwig Andreas von Feuerbach 28 July 1804 Landshut, Electorate of Bavaria |

| Died | 13 September 1872 (aged 68) Rechenberg, German Empire |

| School tradition | Materialism |

| Nationality | German |

Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach (28 July 1804 – 13 September 1872) was a German philosopher who played a crucial role in the development of materialism. His most significant contributions are his materialist critique of Hegelian idealism and his anthropological critique of religion. He represents the pinnacle of pre-Marxist materialism and greatly influenced the Young Hegelians.

Feuerbach played a crucial role in the development of Marx and Engels' philosophical thought, even as they ultimately moved beyond his limitations. By synthesizing Feuerbach's materialism and Hegel's dialectics with their own ideas the pair were able to create dialectical materialism and historical materialism.[1]

Biography[edit | edit source]

Early life and education[edit | edit source]

Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach was born on 28 July 1804 in Landshut, Bavaria, to noted jurist Paul Johann Anselm Ritter von Feuerbach. Ludwig was the fourth of five sons, in age order: Joseph the eldest became a archaeologist, Karl Wilhelm was a mathetician, Eduard August was a jurist and Friedrich was a philosgist and follower of Ludwig's philosophy. Feuerbach's upbringing was privileged and liberal, and he received a government stipend as son of a civil servant.[2][3]

Feuerbach began his studies in theology at the University of Heidelberg in 1823, where he attended lectures by Heinrich Paulus and Karl Daub. Feuerbach was quickly repelled by the rationalized theology of Paulus, later describing it as a "web of sophisms", and stopped attending the lectures. However, the Hegel influenced lectures of Daub inspired in him an interest in philosophy and the desire to head to Berlin, the centre of the Hegelians. In 1824, after problems with his fathers objections and police surveillance,[a] he traveled to Berlin to attend the lectures of Hegel, as well as the theologians Friedrich Schleiermacher and Philip Marheinekehe.[2][3]

In 1825 he enrolled in the faculty of philosophy at the University of Berlin but a year later he had to leave Berlin due to financial problems caused by his government stipend being cut off upon the death of Bavarian King Max Joseph. Returning to the University of Erlangen, Feuerbach planned to study the natural sciences, attending lectures on physiology and anatomy to continue this goal, but his financial problems made continuing impossible. In 1828 he earned his doctoral degree with his dissertation De ratione una, universali, infinita,[b] an early work of Hegelianism that explored the concept of a single, universal, and infinite reason.[3]

Philosopher[edit | edit source]

From 1829 to 1835, Feuerbach lectured on the history of modern philosophy at the University of Erlangen. In 1830 Feuerbach anonymously published his first book, Thoughts on Death and Immortality,[c] which was essentially an attack on theology being used in service of the state. The clergy considered it a revolutionary document that was a threat to reactionary rule and when Feuerbach was recognized as the author he was barred from his university post and any future chance of working in academia.[3]

Feuerbach continued his philosophical work despite these difficulties, producing a three volume work on the history of philosophy with volumes appearing in 1833, 1836 and 1838 respectively which examined philosophers such as Francis Bacon, Baruch Spinoza, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Pierre Bayle. In 1837 Feuerbach met and married Bertha Löw, who was part-owner of a family porcelain factory in Bruckberg, where they moved allowing Feuerbach to continue his work in rustic isolation.[3]

In 1839, he published Critique of Hegelian Philosophy,[d] marking his open break with Hegelian idealism which was was followed up by his most fundamental work,The Essence of Christianity,[e] in 1841. In the early 1840s, Feuerbach became the theoretical leader of the Young Hegelians and he had a profound influence on Marx and Engels in particular. Engels would later write of this period: "We were all Feuerbachians," but he and Marx soon moved beyond Feuerbach's limitations and in 1845 Marx wrote his Theses on Feuerbach.[3][4]

Later life[edit | edit source]

Feuerbach maintained a skeptical attitude toward the Revolution of 1848, though he would later despair at the subsequent reactionary period that resulted from the failure of the revolution and considered moving to the United States. At the invitation of the revolutionary student body, he gave a series of public lectures at the City Hall in Heidelberg from December 1848 to March 1849 on the essence of religion. His next major work was theTheogonie in 1857, which extended the program of The Essence of Christianity with respect to other relgions and Greek and Roman mythology.[4]

In 1860, his wife's porcelain factory went bankrupt, and Feuerbach found himself without a source of income forcing him to move to Rechenberg, near Nuremberg, where he lived until his death. His final major work was Spiritualism and Materialism, which appeared as part of the tenth and final volume of his collected works in 1866. In 1868, Feuerbach read Marx's first volume of Capital enthusiastically, and in 1870, he joined the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). On 13 September 1872, Feuerbach died at the age of 68 and was buried at the Johannisfriedhof in Nuremberg.[4][5]

Philosophy[edit | edit source]

Critique of Hegelian idealism[edit | edit source]

Feuerbach rejected Hegel's objective idealism, which posited that the Absolute Idea (Geist) was the foundation of reality. Instead, Feuerbach insisted that material, natural existence was primary, and that consciousness was derived from material being.

His famous aphorism, "Der Mensch ist, was er isst" ("Man is what he eats"), is a succinct expression of this principle, emphasizing the literal, bodily basis of human life against the abstractions of idealist philosophy.[6]

Critique of religion[edit | edit source]

Feuerbach's most influential work, 'The Essence of Christianity' (1841), argued that religion is a human creation, a projection of humanity's own nature onto an imaginary divine being. God is not the creator of man; rather, man creates God by externalizing and alienating his own human essence.

RELIGION is the disuniting of man from himself; he sets God before him as the antithesis of himself God is not what man is – man is not what God is. God is the infinite, man the finite being; God is perfect, man imperfect; God eternal, man temporal; God almighty, man weak; God holy, man sinful. God and man are extremes: God is the absolutely positive, the sum of all realities; man the absolutely negative, comprehending all negations. But in religion man contemplates his own latent nature. Hence it must be shown that this antithesis, this differencing of God and man, with which religion begins, is a differencing of man with his own nature.[7]

For Feuerbach, theology is merely anthropology in disguise. When humans worship God's love, wisdom, or justice, they are actually worshiping idealized human qualities projected outward.

Critique[edit | edit source]

While Feuerbach broke with idealism, his materialism remained contemplative rather than practical, and mechanical rather than dialectical.

Contemplative, not practical materialism[edit | edit source]

Feuerbach understood reality as an object of contemplation and perception, not as the product of human practical activity.

The chief defect of all hitherto existing materialism – that of Feuerbach included – is that the thing, reality, sensuousness, is conceived only in the form of the object or of contemplation, but not as sensuous human activity, practice, not subjectively. Hence, in contradistinction to materialism, the active side was developed abstractly by idealism – which, of course, does not know real, sensuous activity as such.[8]

Feuerbach's materialism was passive, humans observe and contemplate nature but do not transform it through labor and practice. This meant Feuerbach could not understand that human consciousness and human nature itself are products of historical practice, not eternal givens.

Ahistorical and abstract conception of human nature[edit | edit source]

Feuerbach posited an eternal, unchanging human essence or "species-being" that exists outside of history and social relations. In contrast, Marx contended that "the human essence is no abstraction inherent in each single individual. In its reality, it is the ensemble of the social relations."[9]

Because Feuerbach viewed human nature as a fixed essence rather than as historically produced through social relations and labor, he could not understand how different social structures, particularly modes of production, shape human consciousness, create alienation, and are subject to revolutionary transformation.

Inability to grasp revolutionary practice[edit | edit source]

Feuerbach's contemplative materialism left him unable to understand the transformation of the world through revolutionary practice. Marx's eleventh and most famous thesis on Feuerbach emphasizes this:

The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.[10]

Feuerbach could critique religion intellectually, but he could not understand that religion would only be abolished through the revolutionary transformation of the material conditions that produce religious alienation, i.e., class society and exploitation.

Rejection of dialectics[edit | edit source]

Feuerbach rejected Hegel's dialectics along with his idealism, throwing out the rational kernel with the mystical shell. He failed to develop a materialist dialectics. Without dialectics, Feuerbach could not grasp development, contradiction, and qualitative transformation, the tools necessary for understanding historical change and revolution.

Legacy[edit | edit source]

Feuerbach occupies a unique and indispensable position in the history of philosophy: he represents both the culmination of pre-Marxist materialism and the necessary bridge to dialectical materialism and historical materialism. His influence on the development of Marxism is vast, even as Marx and Engels ultimately transcended his philosophical limitations.

Impact on Marx and Engels[edit | edit source]

Feuerbach's work had an immediate and profound impact on the Young Hegelians, providing the philosophical foundations for their break with Hegelian idealism. His 'Essence of Christianity' (1841) arrived as a philosophical weapon that shattered the dominance of idealist philosophy in German thought. As Engels recalls in 'Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy' (1886):

Then came Feuerbach’s Essence of Christianity[D]. With one blow, it pulverized the contradiction, in that without circumlocutions it placed materialism on the throne again. Nature exists independently of all philosophy. It is the foundation upon which we human beings, ourselves products of nature, have grown up. Nothing exists outside nature and man, and the higher beings our religious fantasies have created are only the fantastic reflection of our own essence. The spell was broken; the “system” was exploded and cast aside, and the contradiction, shown to exist only in our imagination, was dissolved. One must himself have experienced the liberating effect of this book to get an idea of it. Enthusiasm was general; we all became at once Feuerbachians. How enthusiastically Marx greeted the new conception and how much — in spite of all critical reservations — he was influenced by it, one may read in the The Holy Family[E].[11]

Advancements[edit | edit source]

As Marx himself laid down, that the advancements of Feuerbach were of immense importance:

Feuerbach is the only one who has a serious, critical attitude to the Hegelian dialectic and who has made genuine discoveries in this field. He is in fact the true conqueror of the old philosophy. The extent of his achievement, and the unpretentious simplicity with which he, Feuerbach, gives it to the world, stand in striking contrast to the opposite attitude [of the others].

Feuerbach’s great achievement is:

(1) The proof that philosophy is nothing else but religion rendered into thought and expounded by thought, i.e., another form and manner of existence of the estrangement of the essence of man; hence equally to be condemned;

(2) The establishment of true materialism and of real science, by making the social relationship of “man to man” the basic principle of the theory;

(3) His opposing to the negation of the negation, which claims to be the absolute positive, the self-supporting positive, positively based on itself.[12]

Feuerbach's limitations as legacy[edit | edit source]

Feuerbach's most influential legacy may be the clarity with which Marx and Engels identified his limitations. The 'Theses on Feuerbach' (1845) represent not a rejection of Feuerbach but a dialectical Aufhebung, a simultaneous preservation, negation, and transcendence. Marx preserved Feuerbach's materialism, negated his contemplative passivity, and transcended both through the concept of revolutionary practice.

Feuerbach thus stands as both:

- An end point: The culmination of one philosophical tradition (contemplative, ahistorical materialism)

- A beginning: The necessary stepping stone to another (dialectical, historical, revolutionary materialism)

In this sense, Feuerbach's greatest contribution was not what he built, but what he made possible to build beyond him.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ “The separation from Hegelian philosophy was here also the result of a return to the materialist standpoint. That means it was resolved to comprehend the real world — nature and history — just as it presents itself to everyone who approaches it free from preconceived idealist crotchets. It was decided mercilessly to sacrifice every idealist fancy which could not be brought into harmony with the facts conceived in their own and not in a fantastic interconnection. And materialism means nothing more than this. But here the materialistic world outlook was taken really seriously for the first time and was carried through consistently — at least in its basic features — in all domains of knowledge concerned.

Hegel was not simply put aside. On the contrary, a start was made from his revolutionary side, described above, from the dialectical method. But in its Hegelian form, this method was unusable. According to Hegel, dialectics is the self-development of the concept. The absolute concept does not only exist — unknown where — from eternity, it is also the actual living soul of the whole existing world. It develops into itself through all the preliminary stages which are treated at length in the Logic and which are all included in it. Then it “alienates” itself by changing into nature, where, unconscious of itself, disguised as a natural necessity, it goes through a new development and finally returns as man’s consciousness of himself. This self-consciousness then elaborates itself again in history in the crude form until finally the absolute concept again comes to itself completely in the Hegelian philosophy. According to Hegel, therefore, the dialectical development apparent in nature and history — that is, the causal interconnection of the progressive movement from the lower to the higher, which asserts itself through all zigzag movements and temporary retrogression — is only a copy [Abklatsch] of the self-movement of the concept going on from eternity, no one knows where, but at all events independently of any thinking human brain. This ideological perversion had to be done away with. We again took a materialistic view of the thoughts in our heads, regarding them as images [Abbilder] of real things instead of regarding real things as images of this or that stage of the absolute concept. Thus dialectics reduced itself to the science of the general laws of motion, both of the external world and of human thought — two sets of laws which are identical in substance, but differ in their expression in so far as the human mind can apply them consciously, while in nature and also up to now for the most part in human history, these laws assert themselves unconsciously, in the form of external necessity, in the midst of an endless series of seeming accidents. Thereby the dialectic of concepts itself became merely the conscious reflex of the dialectical motion of the real world and thus the dialectic of Hegel was turned over; or rather, turned off its head, on which it was standing, and placed upon its feet. And this materialist dialectic, which for years has been our best working tool and our sharpest weapon, was, remarkably enough, discovered not only by us but also, independently of us and even of Hegel, by a German worker, Joseph Dietzgen. (2)

In this way, however, the revolutionary side of Hegelian philosophy was again taken up and at the same time freed from the idealist trimmings which with Hegel had prevented its consistent execution. The great basic thought that the world is not to be comprehended as a complex of readymade things, but as a complex of processes, in which the things apparently stable no less than their mind images in our heads, the concepts, go through an uninterrupted change of coming into being and passing away, in which, in spite of all seeming accidentally and of all temporary retrogression, a progressive development asserts itself in the end — this great fundamental thought has, especially since the time of Hegel, so thoroughly permeated ordinary consciousness that in this generality it is now scarcely ever contradicted.”

Frederick Engels (1886). [https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1886/ludwig-feuerbach/ch04.htm "Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German PhilosophyPart 4: Marx"] Marxists.org.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Wartofsky, Marx W (1977). Feuerbach: 'Feurbach's Life: A Brief Sketch' (pp. xvii). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Wartofsky, Marx W (1977). Feuerbach: 'Feurbach's Life: A Brief Sketch' (pp. xviii). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Wartofsky, Marx W (1977). Feuerbach: 'Feurbach's Life: A Brief Sketch' (pp. xix). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Wartofsky, Marx W (1977). Feuerbach: 'Feurbach's Life: A Brief Sketch' (pp. xx). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ “Der Mensch ist was er isst.”

Ludwig Feuerbach (1850). "Die Naturwissenschaft und die Revolution" - ↑ “RELIGION is the disuniting of man from himself; he sets God before him as the antithesis of himself God is not what man is – man is not what God is. God is the infinite, man the finite being; God is perfect, man imperfect; God eternal, man temporal; God almighty, man weak; God holy, man sinful. God and man are extremes: God is the absolutely positive, the sum of all realities; man the absolutely negative, comprehending all negations.

But in religion man contemplates his own latent nature. Hence it must be shown that this antithesis, this differencing of God and man, with which religion begins, is a differencing of man with his own nature.”

Ludwig Feuerbach (1841). [https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/feuerbach/works/essence/ec02.htm "Essence of Christianity: PART I, The True or Anthropological Essence of ReligionChapter II. God as a Being of the Understanding"] Marxists.org.

- ↑ “The chief defect of all hitherto existing materialism – that of Feuerbach included – is that the thing, reality, sensuousness, is conceived only in the form of the object or of contemplation, but not as sensuous human activity, practice, not subjectively. Hence, in contradistinction to materialism, the active side was developed abstractly by idealism – which, of course, does not know real, sensuous activity as such.”

Karl Marx (1845). "Theses On Feuerbach" Marxists.org. - ↑ “Feuerbach resolves the religious essence into the human essence. But the human essence is no abstraction inherent in each single individual.

In its reality it is the ensemble of the social relations.

Feuerbach, who does not enter upon a criticism of this real essence, is consequently compelled:

To abstract from the historical process and to fix the religious sentiment as something by itself and to presuppose an abstract – isolated – human individual.

Essence, therefore, can be comprehended only as “genus”, as an internal, dumb generality which naturally unites the many individuals.”

Karl Marx (1845). "Theses On Feuerbach" Marxists.org. - ↑ “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.”

Karl Marx (1845). "Theses On Feuerbach" Marxists.org. - ↑ “Then came Feuerbach’s Essence of Christianity[D]. With one blow, it pulverized the contradiction, in that without circumlocutions it placed materialism on the throne again. Nature exists independently of all philosophy. It is the foundation upon which we human beings, ourselves products of nature, have grown up. Nothing exists outside nature and man, and the higher beings our religious fantasies have created are only the fantastic reflection of our own essence. The spell was broken; the “system” was exploded and cast aside, and the contradiction, shown to exist only in our imagination, was dissolved. One must himself have experienced the liberating effect of this book to get an idea of it. Enthusiasm was general; we all became at once Feuerbachians. How enthusiastically Marx greeted the new conception and how much — in spite of all critical reservations — he was influenced by it, one may read in the The Holy Family[E].”

Frederick Engels (1886). [https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1886/ludwig-feuerbach/ch01.htm "Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German PhilosophyPart 1: Hegel"] Marxists.org.

- ↑ “Feuerbach is the only one who has a serious, critical attitude to the Hegelian dialectic and who has made genuine discoveries in this field. He is in fact the true conqueror of the old philosophy. The extent of his achievement, and the unpretentious simplicity with which he, Feuerbach, gives it to the world, stand in striking contrast to the opposite attitude [of the others].

Feuerbach’s great achievement is:

(1) The proof that philosophy is nothing else but religion rendered into thought and expounded by thought, i.e., another form and manner of existence of the estrangement of the essence of man; hence equally to be condemned;

(2) The establishment of true materialism and of real science, by making the social relationship of “man to man” the basic principle of the theory;

(3) His opposing to the negation of the negation, which claims to be the absolute positive, the self-supporting positive, positively based on itself.”

Karl Marx (1844). [https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/manuscripts/hegel.htm "Economic and Philosophic ManuscriptsCritique of Hegel’s Philosophy in General"] Marxists.org.

Notes[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Following the Carlsbad Decrees of 1819 aimed at supressing the rising sentiment for German unification, pressure on students increased.

- ↑ English:The One, Universal, and Infinite Reason

- ↑ German: Gedanken über Tod und Unsterblichkeit

- ↑ German: Zur Kritik der Hegelschen Philosophie

- ↑ German: Das Wesen des Christenthums