No edit summary Tag: Visual edit |

420dengist (talk | contribs) (expanded the page including some cites of prison notebooks) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

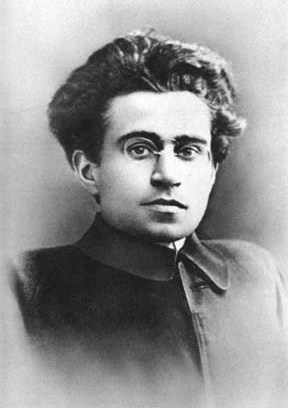

{{Infobox person|name=Antonio Gramsci|image=Gramsci.png|birth_date=22 January 1891|birth_place=Ales, Sardinia, [[Kingdom of Italy|Italy]]|death_date=27 April 1937|death_place=Rome, Italy|nationality=Italian|image_size=150}} | {{Infobox person|name=Antonio Gramsci|image=Gramsci.png|birth_date=22 January 1891|birth_place=Ales, Sardinia, [[Kingdom of Italy|Italy]]|death_date=27 April 1937|death_place=Rome, Italy|nationality=Italian|image_size=150|known=Theory of [[cultural hegemony]]<br>Writing the [[Prison Notebooks]]}} | ||

'''Antonio Gramsci''' was an Italian | '''Antonio Gramsci''' was an [[Italy|Italian]] [[Marxist]], one of the founders and leaders of the [[Italian Communist Party]]. In 1926, he was imprisoned by the [[Fascist Italy|fascist]] regime of[[Benito Mussolini]]; Gramsci eventually died in prison in 1937 due to a mix of several health problems.<ref>{{Citation|author=Antonio Gramsci|year=1971|title=Selections from the Prison Notebooks|chapter=Introduction|page=xvii–xcvi|city=New York City|publisher=International Publishers|isbn=071780397X|title-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=z4vFJ-3jh6sC&dq=isbn:071780397X&hl=de&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi0otjLgsj1AhXckWoFHYfEBVcQ6AF6BAgCEAI}}</ref> In prison, he wrote a famous series of assorted notes and Marxist analyses known as the [[Prison Notebooks]]. | ||

== Political career == | == Political career == | ||

Antonio Gramsci joined the [[Italian Socialist Party]] in 1913. In 1919, he founded a socialist newspaper called ''L'Ordine Nuovo''. In 1921, he founded the Italian Communist Party in Livorno and participated in several [[Communist International (1919–1943)|Comintern]] meetings in the 1920s.<ref name=":0">{{News citation|author=Nicholas Stender|newspaper=[[Liberation School]]|title=Antonio Gramsci: A communist revolutionary, organizer, and theorist|date=2021-01-01|url=https://www.liberationschool.org/antonio-gramsci/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220122170247/https://www.liberationschool.org/antonio-gramsci/|archive-date=2022-01-22|retrieved=2022-06-24}}</ref> | Antonio Gramsci joined the [[Italian Socialist Party]] in 1913. In 1919, he founded a socialist newspaper called ''L'Ordine Nuovo''. In 1921, he founded the Italian Communist Party in Livorno and participated in several [[Communist International (1919–1943)|Comintern]] meetings in the 1920s.<ref name=":0">{{News citation|author=Nicholas Stender|newspaper=[[Liberation School]]|title=Antonio Gramsci: A communist revolutionary, organizer, and theorist|date=2021-01-01|url=https://www.liberationschool.org/antonio-gramsci/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220122170247/https://www.liberationschool.org/antonio-gramsci/|archive-date=2022-01-22|retrieved=2022-06-24}}</ref> | ||

== | == Ideological contributions == | ||

Gramsci believed that trade unions tended towards [[reformism]]. Instead, he preferred factory councils that were similar to the [[Soviet (governmental body)|Soviets]] in [[Russian Empire (1721–1917)|Russia]], which formed [[Dual Power|dual power]] against the bourgeois state. Gramsci also advocated for workers to educate each other on the job and train cadres to popularize [[scientific socialism]].<ref name=":0" /> | Gramsci believed that trade unions tended towards [[reformism]]. Instead, he preferred factory councils that were similar to the [[Soviet (governmental body)|Soviets]] in [[Russian Empire (1721–1917)|Russia]], which formed [[Dual Power|dual power]] against the bourgeois state. Gramsci also advocated for workers to educate each other on the job and train cadres to popularize [[scientific socialism]].<ref name=":0" /> | ||

=== Cultural hegemony === | |||

Perhaps the most well-known of Gramsci's contributions, the concept of cultural hegemony expanded the traditional Marxist understanding of class struggle from the [[Political economy|political-economic]] domain to the cultural and ideological ones. Gramsci argued that the [[ruling class]] maintains power not merely through force or economic control, but also through cultural and ideological means. In Gramsci's view, the ruling class propagates its own values, norms, and ideologies in society, causing these to be accepted as common sense or natural by subordinate classes. In contrast, a revolutionary class can contest cultural hegemony by disseminating its own (e.g. proletarian) ideology.<ref>{{Citation|author=Antonio Gramsci|year=1929--1935|title=Prison Notebooks|chapter=Notebook 1, §44-§48: This section has important early formulations of the concept of hegemony in relation to the state and civil society.<br> | |||

Notebook 5, §78-§80: Here Gramsci reflects on state power, civil society, and the complex interplay of consent and coercion in maintaining cultural hegemony.<br> | |||

Notebook 13, §17: Here Gramsci discusses the balance of force and consent in the process of maintaining state power.|mia=https://www.marxists.org/archive/gramsci/prison_notebooks/index.htm}}</ref> Gramsci considers this an essential part of the struggle for communism. | |||

=== The role of intellectuals === | |||

In addition to his work on cultural hegemony, Gramsci also made significant contributions to our understanding of the role of [[intellectuals]] within society. He argued that every social class generates its own intellectuals, who play a key role in establishing and maintaining that class's cultural hegemony.<ref>Notebook 10, §44: This passage delves into the role of intellectuals in the creation and propagation of hegemony.</ref> | |||

Gramsci distinguished between "traditional" intellectuals, who see themselves as autonomous and independent from the dominant social class, and "organic" intellectuals, who are directly tied to the class for which they articulate ideas and strategies. Gramsci argued that these organic intellectuals play a critical role in enabling the ruling class to exercise cultural hegemony. | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

[[Category:Communists]] | [[Category:Communists]] | ||

Revision as of 13:34, 12 June 2023

Antonio Gramsci | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 22 January 1891 Ales, Sardinia, Italy |

| Died | 27 April 1937 Rome, Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Theory of cultural hegemony Writing the Prison Notebooks |

Antonio Gramsci was an Italian Marxist, one of the founders and leaders of the Italian Communist Party. In 1926, he was imprisoned by the fascist regime ofBenito Mussolini; Gramsci eventually died in prison in 1937 due to a mix of several health problems.[1] In prison, he wrote a famous series of assorted notes and Marxist analyses known as the Prison Notebooks.

Political career

Antonio Gramsci joined the Italian Socialist Party in 1913. In 1919, he founded a socialist newspaper called L'Ordine Nuovo. In 1921, he founded the Italian Communist Party in Livorno and participated in several Comintern meetings in the 1920s.[2]

Ideological contributions

Gramsci believed that trade unions tended towards reformism. Instead, he preferred factory councils that were similar to the Soviets in Russia, which formed dual power against the bourgeois state. Gramsci also advocated for workers to educate each other on the job and train cadres to popularize scientific socialism.[2]

Cultural hegemony

Perhaps the most well-known of Gramsci's contributions, the concept of cultural hegemony expanded the traditional Marxist understanding of class struggle from the political-economic domain to the cultural and ideological ones. Gramsci argued that the ruling class maintains power not merely through force or economic control, but also through cultural and ideological means. In Gramsci's view, the ruling class propagates its own values, norms, and ideologies in society, causing these to be accepted as common sense or natural by subordinate classes. In contrast, a revolutionary class can contest cultural hegemony by disseminating its own (e.g. proletarian) ideology.[3] Gramsci considers this an essential part of the struggle for communism.

The role of intellectuals

In addition to his work on cultural hegemony, Gramsci also made significant contributions to our understanding of the role of intellectuals within society. He argued that every social class generates its own intellectuals, who play a key role in establishing and maintaining that class's cultural hegemony.[4]

Gramsci distinguished between "traditional" intellectuals, who see themselves as autonomous and independent from the dominant social class, and "organic" intellectuals, who are directly tied to the class for which they articulate ideas and strategies. Gramsci argued that these organic intellectuals play a critical role in enabling the ruling class to exercise cultural hegemony.

References

- ↑ Antonio Gramsci (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks: 'Introduction' (pp. xvii–xcvi). New York City: International Publishers. ISBN 071780397X

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Nicholas Stender (2021-01-01). "Antonio Gramsci: A communist revolutionary, organizer, and theorist" Liberation School. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- ↑ Antonio Gramsci (1929--1935). Prison Notebooks: 'Notebook 1, §44-§48: This section has important early formulations of the concept of hegemony in relation to the state and civil society.

Notebook 5, §78-§80: Here Gramsci reflects on state power, civil society, and the complex interplay of consent and coercion in maintaining cultural hegemony.

Notebook 13, §17: Here Gramsci discusses the balance of force and consent in the process of maintaining state power.'. [MIA] - ↑ Notebook 10, §44: This passage delves into the role of intellectuals in the creation and propagation of hegemony.