More languages

More actions

| Country of Sumer and Akkad 𒆳𒋗𒈨𒊒𒆠𒅇𒌵𒆠 | |

|---|---|

| 626 BCE–539 BCE | |

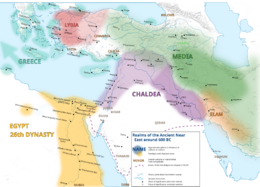

Babylonia (purple) in 600 BCE | |

| Capital | Bābilim |

| Common languages | Akkadian Aramaic |

| Dominant mode of production | Slavery |

| Government | Monarchy |

| History | |

• Established | 626 BCE |

• Dissolution | 539 BCE |

| Area | |

• Total | 500,000 km² |

| Currency | Shekel |

The Country of Sumer and Akkad, also known as the Neo-Babylonian Empire, Late Babylonian Empire, or Chaldean Empire, was the last native kingdom of ancient Mesopotamia.

History[edit | edit source]

Formation[edit | edit source]

Sînšariškun succeeded Aššurbāniapli as king of Assyria in 629 BCE. Nabûaplauṣur, a Chaldean chieftain, began a rebellion and took control of northern Babylon in 626 BCE. He tried to ally with Elam to capture Uruk and led a failed siege of Nippur, which the Assyrians lifted. During the siege, he gained the support of Babylon and crowned himself king of a new dynasty. He captured Uruk in 616 BCE and Nippur the next year but failed to take Aššūr.[1]

In 614 BCE, the Medes surrounded Ninua, the largest city in Assyria, and destroyed Aššūr. After the battle, Nabûaplauṣur formed an alliance with the Medes and married his son Nabûkudurriuṣur to Humati, the daughter of the Median king Huvaxšthra. Sînšariškun resumed the war in 612 BCE, and the combined Chaldean and Median forces captured Ninua after a three-month siege. Part of the Assyrian army retreated north to Harran and continued to fight under the leadership of Aššuruballiṭ II. Two years later, the Medes drove the Assyrians out of Harran, and the Chaldeans occupied the city. The Egyptian pharaoh Nekau II sent an army to support the Assyrians and helped them recapture Harran. However, Nabûaplauṣur's army soon arrived and destroyed the Assyrian army once and for all.[1]

Conquest of Palestine and Phoenicia[edit | edit source]

After the fall of Assyria, the Medes took control of Harran and the Assyrian homeland. The Babylonians and Egyptians both claimed Palestine and Syria. In 607 BCE, Nabûaplauṣur gave his son control of the army. In 605 BCE, the Babylonians crossed the Euphrates and destroyed the city of Karkemish, which contained an Egyptian garrison and its Greek mercenaries. After defeating Egypt, the Babylonians were able to take over most of Palestine and Syria without resistance. Later that year, Nabûaplauṣur died and Nabûkudurriuṣur became king. In 604 BCE, he captured the Phoenician city of ʾAšqalōn, whose ruler sent a letter asking for Egyptian support. In 601 BCE, the Babylonians fought against the Egyptians, and both sides suffered heavy losses.[1]

In 598 BCE, Yəhōyāqīm of Judah ended his alliance with Babylon at the request of Nekau. In response, Nabûkudurriuṣur besieged Jerusalem and captured it in early 597 BCE. He installed Ṣīḏqīyyāhū as the new king. In late 595 and early 594 BCE, a rebellion broke out in the army. The king oversaw a military tribunal that sentenced the leading conspirator to death. The pharaoh Wahibra seized the cities of Gaza, Ṣīdūn, Ṣūr and backed a Judean rebellion against Babylon in an attempt to take control of Phoenicia. In 587 BCE, the Babylonians recaptured Jerusalem after an 18-month siege and annexed Judah. They exiled King Ṣīḏqīyyāhū and thousands of his nobles and craftsmen to other parts of the empire. The Babylonians then besieged the Phoenician city of Ṣūr for another 13 years.[1]

Internal conflicts[edit | edit source]

The clergy and nobility expanded their power after Nabûkudurriuṣur's death in 562 BCE and removed kings they opposed. Nabûkudurriuṣur's son Amēlmarduk was only able to rule for two years before Nergalšaruṣur overthrew him. Nergalšaruṣur's son and successor Lâbâšimarduk only ruled for three months before being killed. Nabûnaʾid, who was an Aramean and not a Chaldean, became the king in 556 BCE. His religious reforms caused a conflict with the clergy.[1]

Persian conquest[edit | edit source]

In 553 BCE, the Medes removed their garrison in Harran in order to fight the Persians. Nabûnaʾid recaptured Harran and restored the temple of Sîn destroyed during the war with the Assyrians. He also conquered Taymāʾ in Central Arabia and took control of its caravan routes to Egypt. He moved his residence to Taymāʾ and gave his son Bēlšaruṣur control of the Babylonian administration. In 546 BCE, Egypt allied with Babylon in order to prepare for the Persian invasion.[1]

The priests of Marduk were disloyal to Nabûnaʾid because of his religious reforms, and the merchants wanted the rule of a great power to stabilize their markets and trade routes. The peoples conquered by the Babylonians, many of whom had been deported to Babylon itself, welcomed the Persians as liberators. In October 539 BCE, Persian forces led by Kūruš II finally conquered Babylonia.[1]

Government[edit | edit source]

Free citizens, including all craftsmen, merchants, officials, priests, and free farmers, could participate in the popular assembly. They lived in cities and could participate in court cases over marital and property disputes. They were attached to a certain temple and received some of its income from tithes. Foreigners sometimes had local self-government but had no civil rights and could not participate in the popular assembly. Unlike cities, rural areas had no self-government.[1]

Economy[edit | edit source]

The Babylonian economy included both slaves and free workers. Slave labor was used for difficult and unskilled jobs, while more complex work usually involved free workers. Free workers had high wages and were sometimes hired from other countries to work during the harvest before returning home. Others worked year-round.[1]

Temples owned large amounts of land and slaves and engaged in commerce and usury. The population had to pay about 10% of their income to the temples and usually paid in food or wool.[1]

Slaves were allowed to own and sell property and could take disputes to court (but not against their owners). They could buy other slaves or hire free workers, but they could not buy their own freedom. As slavery became less profitable, owners began giving their slaves some property and having them work on their own while paying quit-rent to their master. On average, the annual quit-rent was 12 shekels.[1]

Agriculture[edit | edit source]

Agriculture was the largest part of the Babylonian economy, and the country relied on irrigation because of its low precipitation. The king, temples, and private individuals all owned irrigation canals. Barley was the most important crop, and people also farmed dates, flax, peas, sesame, spelt, and wheat.[1]

Most farmers were not enslaved. The temples, king, and other large landowners divided their own lands into small holdings and leased them to free peasants. Some commoners also farmed their own land.[1]

Commerce[edit | edit source]

Babylonia exported grain and wool to other regions such as Anatolia, Egypt, Elam, and Phoenicia. It imported alum, copper, iron tin, wine, and wood.[1]

Silver was used as currency and was measured in shekels (8.4 grams). Shekels were not shaped into coins and had to be weighed at each use. One shekel was enough to buy six bushels of barley or dates, and a slave cost 60 to 90 shekels. Gold was traded as a commodity but was not money.[1]

The House of Egibi, which was active from the eighth through fifth centuries BCE, issued loans and bought and sold houses, land, and slaves. It was also involved in foreign trade. Another business, the House of Murašû, rented out officials' and military colonists' lands. Unlike modern banks, it dealt in land and not money, although it paid taxes in both commodities and money. It sold food domestically and loaned money to landowners, who often could not pay their loans back.[1]

Creditors could have insolvent debtors arrested and imprisoned, and the debtor had to work to repay their debt. Creditors could not sell debtors as slaves, but they could sell their children. Debt slavery did not have any time limit as it did during the Old Babylonian period.[1]

Manufacturing[edit | edit source]

Craftsmen worked as bakers, blacksmiths, brewers, builders, carpenters, coppersmiths, jewelers, launders, masons, and weavers. They usually sold their goods according to contracts but sometimes sold them on the market. Handicrafts usually relied on free artisans, but some large businesses owned dozens or even hundreds of slaves.[1]

Religion[edit | edit source]

The ancient Babylonians had a polytheistic religion that included gods such as Marduk, Nabû, Nergal, Šamaš, and Sîn. Marduk was traditionally the main god. At the end of the empire, Nabûnaʾid instead promoted the moon god Sîn as the main god during his reign. He adopted Aramean religious practices in order to gain the support of the Aramean tribes living across the empire.[1]