More languages

More actions

| Republic of Zimbabwe Nyika yeZimbabwe Ilizwe leZimbabwe Dziko la Zimbabwe Nyika ye Zimbabwe Hango yeZimbabwe Zimbabwe Nù Inyika yeZimbabwe Nyika yeZimbabwe Tiko ra Zimbabwe Naha ya Zimbabwe Cisi ca Zimbabwe Shango ḽa Zimbabwe Ilizwe lase-Zimbabwe | |

|---|---|

Motto: Unity, Freedom, Work | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Harare |

| Official languages | Chewa, Chibarwe, English (used in education, government, and commerce), Kalanga, Khoisan, Nambya, Ndau, Ndebele, Shangani, Shona, Zimbabwean sign language, Sotho, Tonga, Tswana, Venda, and Xhosa |

| Demonym(s) | Zimbabwean |

| Dominant mode of production | Capitalism |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

• President | Emmerson Mnangagwa |

• Vice-President | Constantino Chiwenga |

| History | |

| 11 November 1965 | |

| 2 March 1970 | |

| 1 June 1979 | |

| 18 April 1980 | |

| 15 May 2013 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 390,757 km² (60th) |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 15,178,979[1] |

| Currency | Zimbabwean dollar United States dollar |

Zimbabwe, officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa. It is bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and Mozambique to the east. The capital and largest city is Harare.

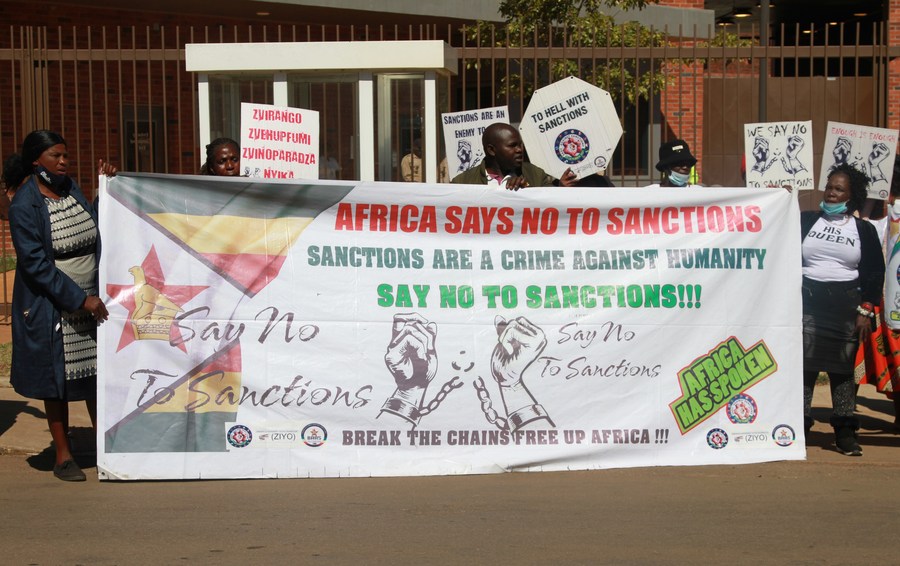

Zimbabwe has been subjected to intense sanctions from imperialist powers, mainly in response to land reform policies that expropriated land from white settlers.[2]

The area that is now modern Zimbabwe was known during the British colonial period as Southern Rhodesia, named for imperialist businessman Cecil Rhodes. In 1965, the settler colony broke from the United Kingdom with the purpose of maintaining white minority rule.[3] The national liberation struggle against the settler regime greatly intensified in the 1970s period of the liberation war. Following this, a 1979 conference led to an agreement on a new constitution for an independent Zimbabwe, transitional governance, and a ceasefire,[4] followed by general elections in 1980 and independence on April 18, 1980.[5]

An article in Liberation News describes the western imperialist hostility toward Zimbabwe, saying: "hostility stems first and foremost from the fact that Zimbabwe's government has its origin in the armed struggle that ended the Western-backed racist, fascist settler regime. U.S. and British opposition to the government reached a crescendo as the Mugabe government moved to confiscate and redistribute the commercial agricultural land owned by white farmers. This land constituted 70 percent of the country’s prime farmlands."[2]

History[edit | edit source]

Early history[edit | edit source]

The country which is now known as Zimbabwe has been inhabited by many different peoples and kingdoms with complex relationships throughout history and was not a single geographical entity before its colonial occupation by the British.[6] As noted in an article on the Government of Zimbabwe website, "the political, social, and economic, relations of these groups were complex, dynamic, fluid and always changing. They were characterised by both conflict and co-operation." The region's history includes the rise and fall of several large and influential states as well as people living in smaller forms of social organization.[5]

The city of Great Zimbabwe existed from 1100 to 1500 CE and had a population of 20,000. It controlled over 100,000 km² of territory between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers, and its economy relied on cattle, farming, and trade of ivory, copper, gold, and slaves.[7] Great Zimbabwe is also noted for its long-distance and regional trade, including trade with China, India, West Asia, East and West Africa, among other regional and inter-regional areas. Other notable states which emerged in pre-colonial Zimbabwe include the Mutapa State, the Rozvi State, the Torwa state, Rozvi states and the Ndebele state. An article on the Government of Zimbabwe's website notes that while these large and influential pre-colonial states of Zimbabwe are a source of pride, the majority of Zimbabweans lived in smaller units, with pre-colonial Zimbabwe societies mainly being farming communities and pastoralists. The article also notes that cattle were an important indicator of wealth and that gold mining was a seasonal activity conducted mainly in summer and winter.[5]

As explained on the Government of Zimbabwe's website, pre-colonial Zimbabwe was a multi-ethnic society inhabited by the Shangni/Tsonga in the south-eastern parts of the Zimbabwe plateau, the Venda in the south, the Tonga in the north, the Kalanga and Ndebele in the south-west, the Karanga in the southern parts of the plateau, the Zezuru and Korekore in the northern and central parts, and finally, the Manyika and Ndau in the east. The article notes that scholars have tended to lump these groups into two broad categories, the Ndebele and Shona, "largely because of their broadly similar languages, beliefs and institutions" and describes the term "Shona" as an anachronism that did not exist until the 19th century, an exonym originally coined as an insult, and which "conflates linguistic, cultural and political attributes of ethnically related people."[5]

Portuguese colonialism[edit | edit source]

During the 1500s, the Portuguese reached the Mutapa state and attempted to convert the royal family to Christianity. Though initially achieving some success, eventually the King renounced Christianity. The killing of a Portuguese missionary prompted punitive expeditions by the Portuguese, and they began interfering more in the region, demanding treaties of vassalage from a rival claimant of the Mutapa kingship and using slaves to work the land they acquired in these treaties (on estates known as prazos), resulting in many armed conflicts in the region. Eventually, the Portuguese were successfully driven out throughout the 1680s and 1690s, with Portuguese mercantilism no longer gaining a serious foothold in Zimbabwe.[5]

Europe's "Scramble for Africa"[edit | edit source]

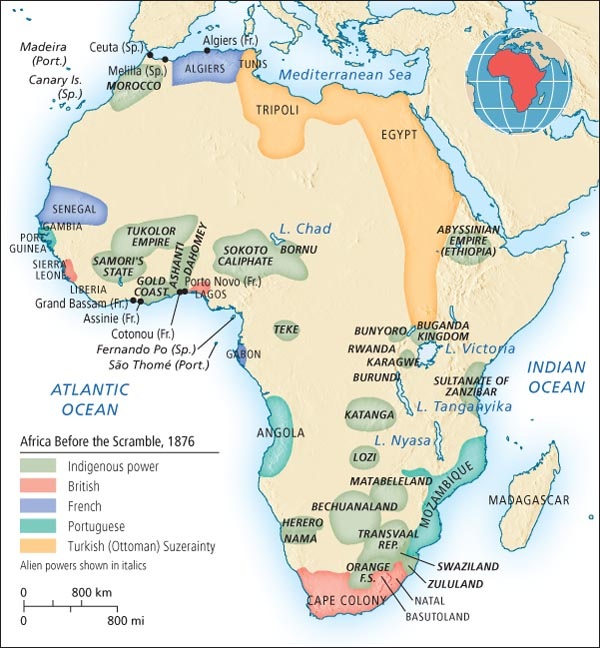

After the expulsion of the Portuguese, internal regional affairs of Zimbabwe continued to unfold, while other effects of the European colonization of Africa led to changes throughout the continent, with the area that corresponds to present-day Zimbabwe becoming one of many points of geostrategic interest for the competing powers.

Over time, the Rozvi state encountered various difficulties, and eventually, came into conflict with Ndebele in the 1850s, resulting in the Ndebele state coming to prominence. According to South Africa History Online, by 1873 "the Ndebele was a consolidated state and at the height of their power."[6] The Government of Zimbabwe website describes this period in the following way, highlighting the interplay of the kingdom's own regional affairs as well as the increasing threat of instability posed by outside influences:

The Ndebele had to establish a strong military presence to establish their authority in their newly acquired land. Besides subduing the original Shona rulers, they had to content with the Boers from the Transvaal who in 1847 crossed the Limpopo and destroyed some Ndebele villages in the periphery of Ndebele country. Then there were the numerous hunters and adventurers who also entered the country to the south. Over and above these were the missionaries and traders; all these groups threatened the internal security and stability of the kingdom.[5]

By the late 1800s, the European colonizers were increasing their efforts to conquer Africa, and the "scramble for Africa" was formalized with the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, with the formal partitioning of Africa to exploit its people and resources for colonial interests. The British thus began their incursions into the region later known as Zimbabwe in the 1880s.[6]

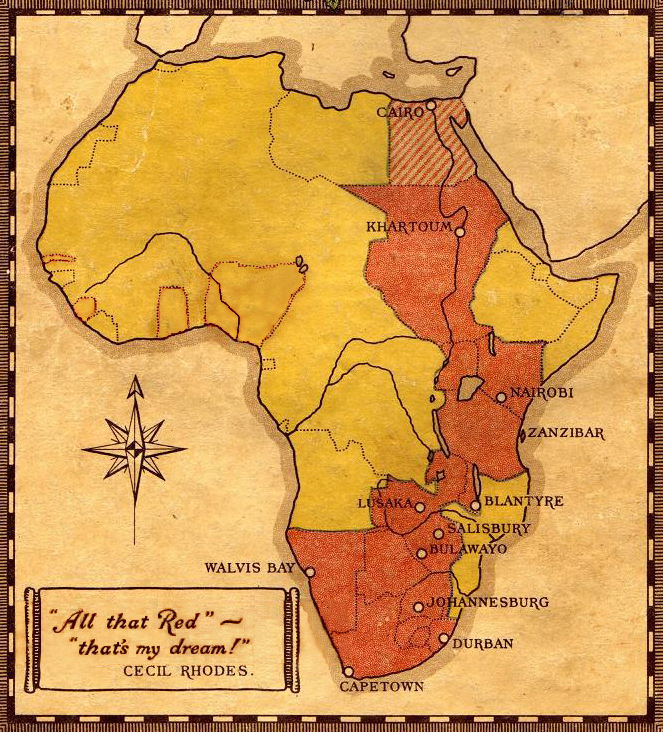

Among the European powers colonizing Africa, there were various competing designs for how to link up their own occupied areas into vast unbroken territories. British colonialist Cecil Rhodes, then active in business and politics in South Africa, was a proponent of expanding the British empire and of linking up British-occupied territory, a concept encapsulated in the vision of a "Cape to Cairo" railway. This vision would conflict with ideas such as Germany's aims of consolidating "Mittelafrika" which would span from the Atlantic to Indian Ocean, which, if realized, would block the north-south connection of Rhodes' plan. Given the geopolitical outlook of the time, Rhodes reasoned that the most viable path to his vision would be to seize the areas of Mashonaland and Matabeleland, then ruled by King Lobengula, an area which corresponds roughly to present-day Zimbabwe. In addition, Rhodes was drawn to this region by rumors of sources of gold.[8]

The Government of Zimbabwe website describes the role of missionaries in the colonization process as well:

[M]issionaries were the earliest representatives of the imperial world that eventually violently conquered the Shona and the Ndebele. They aimed as reconstructing the African world in name of God and Europe civilisation, but in the process facilitating the colonisation of Zimbabwe. [...] Missionaries were consistent and persistent in denigrating and castigating African cultural and religions beliefs/practices as pagan, demonic and evil.[5]

The article further notes that it was missionaries (such as Rev. Charles Helm)[8] who assisted Cecil Rhodes and his accomplice Charles Rudd in misrepresenting the contents of a document to King Lobengula, known as the Rudd Concession, inducing him to sign it under false pretenses, and thereby unintentionally ceding land and mineral rights to Rhodes. The article states that some positives did come from the missionaries, along with the abuses, and that in light of these ambiguities, the "African response to Christianity remained ambivalent."[5]

Rudd Concession[edit | edit source]

A so-called concession, known as the Rudd Concession, which Cecil Rhodes' delegation misrepresented to King Lobengula as they induced him to sign it, granted the company "the complete and exclusive charge over all metals and minerals" in the region, as well as "full power to do all things that they may deem necessary to win and procure the same," which the company used as permission to seize land and obtain a royal charter (which was granted in 1889).[9][10]

Following this, Lobengula learned what the actual contents of the document had been, and sent a letter to Queen Victoria explaining the deliberate deception and that he would not recognize the document as valid. An official response advised Lobengula that it would be "impossible" for him to exclude white men looking for gold in his land, along with giving advice on how to manage their presence there to give the "least trouble to himself and his tribe", and expressed the Queen's approval of Lobengula's so-called concession.[9][11]

Settlers seize the land[edit | edit source]

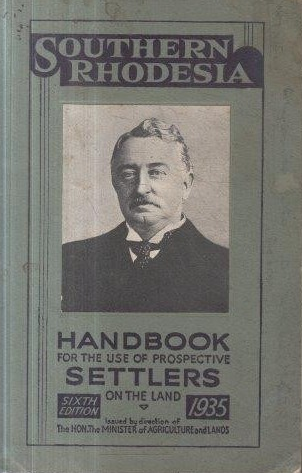

The British South African Company (BSAC) sought to produce a profit for its founder, Cecil Rhodes, and its other investors, in addition to expanding the British empire. Thus they sought to colonize the region, which they called "Southern Rhodesia", and which they believed to be rich in gold and other valuable minerals. However, the company itself was not interested in prospecting and mining the minerals themselves, but rather sought to profit through taxation, by enticing European settlers to move to Southern Rhodesia to do the prospecting and mining, with BSAC receiving royalties on all mined minerals:

To attract European settlers the BSAC publicized reports of the potential mineral wealth of Zimbabwe and promised each settler 15 mining claims and large tracks of land (3,175 acres per settler) on which to prospect for minerals. Minerals found and mined by the settlers would belong to them, but they would have to have to pay royalties (taxes) to the Company on all mined minerals.[12]

In addition, BSAC assembled the "Pioneer Column" to occupy the region and establish company rule, again recruiting these settlers with land offers. As the Government of Zimbabwe website summarizes:

In 1890, Rhodes unleashed the Pioneer Column to invade Mashonaland, marking the beginning of white settler occupation of Zimbabwe. The Shona were not quick to respond to the invasion as they wrongly assumed the column was merely a uniquely large trade and gold-seeking party that would soon vacate. Soon Rhodes’ invading British South Africa Company (BSAC) established a Native Department that authorised labour and tax raids on the Shona. Henceforth, constant skirmishes between Shona communities and tax collectors and labour raiders ensued as the Shona, who had not been conquered at all, saw no premise upon which the company could demand tax and labour from them. More significantly, however, the company started appropriating and granting land to the settler pioneers.[5]

After the formation of Southern Rhodesia, the settlers failed to find the large gold and mineral deposits they had expected to profit from. Both BSAC and the settlers were desperate to find alternative sources of income and wealth, and looked to agricultural production as their alternative, leading them to pursue further territorial expansion.[12]

Seeking dominance over the land, in October 1893, British troops and volunteers crossed into King Lobengula's territory of Matabeleland. As noted by author Gregory Elich, "the entire region rapidly fell into their hands as they inflicted heavy casualties on the Ndebele. Under terms of the resulting Victoria Agreement, each volunteer was entitled to 6,000 acres of land. Rather than an organized division of land, there was instead a mad race to grab the best land," with 10,000 square miles of the most fertile land being seized from its inhabitants within the first year. White settlers also confiscated most of the Ndebele's cattle, Elich notes, "a devastating loss to a cattle-ranching society such as the Ndebele."[9]

The settlers, who were relatively few in number yet had seized large tracts of land in their violent acts of primitive accumulation, now required people to work the land, and thus "the Ndebele became forced laborers on the land they once owned, essentially treated as slaves."[9] The Shona were also robbed of their cattle, as well as subjected to onerous taxes and forced labor, and local women were faced with sexual violence.[5]

The Government of Zimbabwe website explains that despite spirited resistance at the Battles of Mbembezi River, Shangani River and at Pupu across the Shangani River, the Ndebele were defeated in October 1893, leading Lobengula to set fire to his capital and flee to the north, never to be seen again, dead or alive. However, some Ndebele forces remained and would later rise up again against the colonizers. Likewise, the Shona would also rise up in the face of the colonizing forces. These uprisings, which occurred in 1896, are termed the First Chimurenga, and formed the basis of later mass nationalism and inspiration during the Second Chimurenga in the mid-1960s.[5]

Early colonial rule[edit | edit source]

Native Reserves[edit | edit source]

In 1894, the first of seven Land Commissions was established by the colonial regime. The colonizers soon established two reserves (in the arid locations of Gwai and Shangani) to which the Ndebele would be expelled, so as to protect the settlers while they stole the Ndebele's land, and to free up more attractive lands for the settlers while forcing the indigenous inhabitants into less desirable locations. In the following years, more "Native Reserves" (later called "Tribal Trust Lands") were created to expel Ndebele and Shona people to as the settler project proceeded with taking over the more fertile lands.[12]

Undermining indigenous agricultural production[edit | edit source]

As noted by the Government of Zimbabwe's history article, an early challenge for the colonial regime "was how to rule the Shona and Ndebele in an exploitative way, but without provoking another uprising." The article notes that land dispossession and forced proletarianization helped to secure the key aim of "maximum output premised on minimum cost", and was achieved through "restricting African access to land, thus undercutting African peasant agricultural production, increasing taxation and hence forcing Africans to sell their labour cheaply to white mine owners and farmers."[5]

Historian Alois S. Mlambo explains that in the early years, the settlers and colonial economy depended almost entirely on African labor and that the shortage of African labor was a "perennial problem" for the regime, resulting in part from the indigenous population's reluctance to work for a wage when they could meet most of their needs through independent agriculture and the sale of their produce to the settler population. Due to this state of affairs, white farmers and miners continually demanded that the state pass measures to force Africans into the labor market.[13]

South Africa History Online describes the process and methods in the following way:

Land was taken away from Africans and heavy taxes imposed as a way of forcing them into wage labour. As small scale farmers the African people in Rhodesia were self sufficient and had no need for seeking wage labour in the white cities. Yet the settlers needed cheap labour to work in mines, farms and factories around the colony. By taking away land and imposing what is called a “hut-tax” local people were forced to get jobs in the colonial economy. There were also put into place laws which forced Shona and Ndebele people to sign long-term contracts which forced them to stay in labour compounds. The result of these laws were that black people become slave labour in the white economy.[6]

The early period of the colonial regime was still focused largely on mining, though over time, the focus began to shift to agriculture as it became more apparent that the rumored massive gold reserves BSAC expected were not to be found. In this period, the settlers' mines and emerging towns obtained agricultural products primarily from indigenous peasant farmers, with settlers engaging in relatively minor agricultural activity themselves. As the settlers' agricultural sector gradually grew (as they were expelling the indigenous population to arid reserves, stealing their land, and otherwise restricting native people from land access), competition from African farmers still left white farming ventures in a precarious position. By 1908, a "white agriculture policy" was put forth by the colonial regime to boost the viability of white farmers who had previously been dependent on indigenous farmers:

Until white agriculture became established, however, the expansion of peasant production was allowed, as the settler community depended on it. This was soon to change as white commercial agriculture developed as a result of a vigorous state policy and a concerted campaign to promote white agriculture which was based on a multi-pronged white agriculture policy. This began with the creation of an Estates Department in 1908 to promote European settlement and to handle all applications for land.[13]

The government campaign to promote white agriculture included free agricultural training for white farmers; the establishment of a Land Bank to provide white farmers with loans for the purchase of farms, livestock, and equipment and for farm improvements such as irrigation and fencing; other inputs were offered at subsidized prices; and infrastructural projects were undertaken to improve the roads and irrigation near white settlements.[13] White farmers also benefitted by legislation such as the 1934 Maize Control Act which instituted two different prices for maize, with European farmers being paid a governmental guaranteed price for their maize that African farmers were not eligible for, instead having to sell on the open market with no price support. Meanwhile, the Cattle Levy Act placed a special tax on each head of cattle sold by African farmers, a tax from which European farmers were exempt.[12]

While white settlers were being aided by these policies, indigenous Zimbabweans continued to have their land stolen and be expelled to arid reserves, and indigenous farmers thus came under increasing pressure. By the 1930s, Africans were not allowed to own land outside the reserves, and most reserves were severely overcrowded with few employment opportunities for landless Zimbabweans.[9] Alois S. Mlambo notes that the reserves to which Africans were sent were not only poor agricultural land, but also far away from major transportation lines and market towns, further contributing to eliminating African competition in the market.[13] As the Government of Zimbabwe's website summarizes, "White commercial production was promoted on the back of the destruction of African peasant production. This wanton undercutting of African peasant production marked the beginning of the underdevelopment of African reserves in Rhodesia and the forcible proletarianisation of the African."[5]

Indigenous responses to settler regime[edit | edit source]

The various responses by indigenous Zimbabweans to the settler regime ranged from "outright resistance and acquiescence to adopting and adapting Christian ideologies and use of petitions for the return of Ndebele land alienated by the settlers."[5] By 1923, there was the Southern Rhodesia Bantu Voters Association, which though "largely an elitist organisation" is noted for its "vibrant Women’s league". Also significant was "the formation of African churches that broke away from the orthodox Christian churches to ameliorate the impact of colonialism" and the Industrial and Commercial Workers' Union (ICU)[5] which was active in several countries in Southern Africa.[14] Clements Kadalie, founder of the ICU, described how working and witnessing conditions in Southern Rhodesia had influenced him: "I had worked as a clerk in two leading mines in Southern Rhodesia, where I watched the evils of the recruiting system [...] it was the systematic torture of the African people in Southern Rhodesia that kindled the spirit of revolt in me."[15]

Native Registration Act and Native Pass Act[edit | edit source]

In an effort to control the movement of Zimbabweans, two acts of legislation were passed in 1935 and 1936, namely the 1935 Native Registration Act and the 1936 Native Pass Act. Together, these acts required all Zimbabwean Africans to be assigned and registered to a Tribal Trust Land (or TTL, and previously known as Native Reserves), even if they had never lived there before. Every adult African was issued and required to carry a registration book containing their identification information including their assigned TTL. Adults were required to have permission in the form of a written and stamped pass from the local district officer any time they left their assigned TTL, and if they were caught without their passes they could be arrested and sent back to their assigned TTL.[12]

Impacts and aftermath of Second World War[edit | edit source]

During the Second World War, thousands of Africans from Southern Rhodesia actively participated in the fighting, while others were involved in the production of food and minerals for the war effort. The period during the war and the immediate years after saw various political, social, and economic changes as African nationalist consciousness shifted away from reformist tendencies,[5] the settler regime continued forced relocations of Africans and stealing their land and cattle to give to settlers (including land awarded to white servicemen returning from the war),[13] and significant demographic shifts and economic changes occurred in the population post-war.[5][13]

Shifts in political consciousness and activity[edit | edit source]

The Government of Zimbabwe's history article explains that the war resulted in a significant transformation of the political consciousness of Africans. According to the article, while fighting side by side with whites, Africans "came face to face with shortcomings of the white man which debunked the notions of white invincibility and superiority" as well as being "exposed to contemporary thoughts and ideas on self-determination and equality." Such experiences and observations during the war led to a shift away from requesting fairness and accommodation from white governance structures, and instead more toward seeking self-rule.[5]

This period also included notable agitation by trade unionists, such as a railway workers strike in 1945, and student strikes, as well as other protest movements expressed by the Southern Rhodesia Bantu Congress as the Southern Rhodesia African Native Congress, the Voters League, and the creation of the African Methodist Church.[5] A 1948 general strike in Bulawayo demanding better wages spread nationally within days.[16]

Mass confiscations and forced relocations[edit | edit source]

Also during this period, the colonial government took measures supposedly to address the degradation of land quality in the Tribal Trust Lands, by limiting the amount of livestock permitted on the land. This entailed pressuring and threatening Africans into selling their "surplus" cattle against their wishes and at low prices, with some cattle being "sold" without the owner's presence nor consent. The cattle were then "entrusted" to white settlers who were paid by the Cold Storage Commission to look after them, amounting to a mass transfer of Africans' cattle to white ownership.[13]

Despite being blamed on too much livestock and supposedly bad farming techniques, the degradation of the land was in actuality mainly due to overcrowding caused by the colonial policies of forcing people to live in reserves, such as in 1944 when the government forcibly removed thousands of Africans from their traditional home areas in order to open up more land to give as a reward to white servicemen after their time at the war front. However, environmental problems in the Native Reserves continued to be blamed on too many cattle and allegedly poor farming practices by Africans, rather than on the severe overcrowding caused by the forced relocations, providing a narrative for the settler regime to continue transferring cattle from Africans to whites.[13]

Other social and economic changes[edit | edit source]

Another impact of the war was the expansion of the manufacturing and industrial sector. This emerging sector demanded a larger urban-based labor force, prompting policies which further pushed over 100,000 Africans off of the land and into the cities.[5]

In the immediate post-war years, there was a large influx of white immigration, resulting in further displacement of African communities as well as fueling an increase in inter-racial tensions. Tensions also arose between the newer and older white settlers, who tended to hold somewhat different views on how best to administer the settler regime--that is, whether to maintain strict white rule or to make some concessions to avert the growth of militant African nationalism.[5]

The post-war era also saw the growth of an African middle class of educated professionals whose concerns and aspirations "initially tended to run counter to those of the ordinary masses."[5]

Sanctions[edit | edit source]

See also: Economic sanctions#Zimbabwe

According to Chidiebere C. Ogbonna in the African Research Review, from 1966 until the present, "Zimbabwe at one time or another has been under sanctions either by the United Nations the United States, the European Union or all the aforementioned. In total, Zimbabwe has been sanctioned in seven sanction-episodes: 1966, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2005, 2008 and 2009, making it one of the most sanctioned countries in the world." Ogbonna states that in a simple analysis, Zimbabwe has become a regular candidate of the "sanctions industry."[17]

According to a 2022 article by Xinhua News, the U.S. sanctions against Zimbabwe have accumulated since 2001, following a government decision to repossess land from minority white farmers for redistribution to landless indigenous Zimbabweans. The Xinhua article notes that though the Zimbabwean government said the land reform would promote democracy and the economy, "Western countries launched repeated sanctions with little regard for the average person's suffering." Linda Masarira, president of the Labour Economists and Afrikan Democrats (LEAD) political party, said sanctions have been used as a tool of economic warfare against Zimbabwe, and that sanctioning Zimbabwe "was an action that the United States of America decided to do on Zimbabwe to ensure that they make our economy scream, they make things hard for Zimbabweans and imply that black Zimbabweans, native Zimbabweans cannot do their own farming, or run their own economy."[18]

Economy[edit | edit source]

As a state which was afflicted with settler-colonialism and later successfully overcame the settler regime, while still having to contend with Western imperialism and neoliberal economic policies to this day, control over land and the economic distortions wrought by settler-colonialism have been key issues in Zimbabwe's economic development. Zimbabwe's present-day economic conditions must be considered in this context, with attention given both to Zimbabwe's local conditions as well as to Western imperialists' past and present efforts to hamper Zimbabwe's land redistribution process through methods such as unfavorable negotiations, dropped agreements, neoliberal structural adjustment programs, sanctions, and credit freezes.[19]

The Zimbabwe government's attempts to develop its economy and infrastructure through foreign investment have also been noted as a target for Western influence operations. At a US Embassy-funded "workshop" for journalism in 2021, US government officials bragged that they had sponsored media institutions to promote "accountability issues", as part of a strategy to discredit Chinese investment and encourage pro-Western sentiment in the country.[20]

Mining[edit | edit source]

Zimbabwe has the largest lithium supply in Africa. In December 2022, the government banned raw lithium exports in order to process it into batteries in Zimbabwe.[21]

Agriculture[edit | edit source]

In regard to the common insinuation made by Western critics that indigenous Zimbabweans are incompetent farmers compared to the white settler commercial farm owners, land policy analyst Sam Moyo explained in a 2009 article that Zimbabwe's peasants and urban residents' gardens have always produced the majority of food consumed by the majority of Zimbabweans, while large white producers primarily produced for export, generally making products which the majority of the local population could not afford:

[C]lose to 70% of the food consumed by the 80% of Zimbabweans who are the working classes (peasants, formal and informal wage workers, the unemployed) and over 50% of the middle class foods, which comprise mainly grains (maize, sorghum, groundnuts and pulses as oils or for direct eating) and local relish (greens) have always been produced by the peasants and urban residents’ gardens. [...] by far the largest outputs (in volumes and value) produced by large farmers were destined for exports (tobacco, sugar, tea, coffee, horticulture, beef, etc.) and for the local industry (soaps, etc.). Although their exports were critical for forex (40% of national forex was from agriculture, but peasants produced 80% of the cotton and its attendant forex), they were not the main supplier of the food consumed by most of the population, who could not afford their products.[22]

Moyo states that there was a clear division of production between peasants and large farmers, with the peasants producing most of the cheaper and bulkier foods, and large farmers producing foods generally consumed by fewer people.

Addressing issues in the production of bulk foods such as maize, Moyo attributed it mainly to a decline in seed and fertilizer supply and reduced private and external financing. Extremely low input supplies (resulting from Western sanctions), combined with climate effects such as droughts and rain variability, reduced rain-fed maize production by the peasantry, as 90% of the irrigation resources were held by large farmers, including the sugar estates.[22]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ https://zimbabwe.opendataforafrica.org/anjlptc/2022-population-housing-census-preliminary

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Covington, Arthur. “Zimbabwe’s People Reject Imperialist Intervention.” Liberation News. June 2005. Archived 2022-11-15.

- ↑ The New York Times. “Rhodesia’s Dead — but White Supremacists Have given It New Life Online (Published 2018)” Archived 2022-11-10.

- ↑ Chirenje, J. Mutero. "A history of Zimbabwe for primary schools." Longman Zimbabwe, Harare, 1982.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 "History of Zimbabwe." About Zimbabwe, Official Government of Zimbabwe Web Portal. Archived 2024-04-12.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "Zimbabwe." South African History Online. Archived 2023-02-25.

- ↑ Neil Faulkner (2013). A Marxist History of the World: From Neanderthals to Neoliberals: 'The First Class Societies' (p. 19). [PDF] Pluto Press. ISBN 9781849648639 [LG]

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Drohan, Madelaine. "Making a Killing: How and Why Corporations Use Armed Force to do Business." Ch. 1, Cecil Rhodes and the British South Africa Company. Random House Canada, 2003.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Elich, Gregory. "Zimbabwe Under Siege." August 26, 2002, GregoryElich.org. Archived 2024-04-13.

- ↑ "Rudd Concession by King Lobengula of Matabeleland (1888)." South African History Online. Archived 2024-02-03.

- ↑ "MOTION FOR ADJOURNMENT." HC Deb 09, November 1893, vol 18 cc543-627. UK Parliament. Archived 2022-08-11.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 "The Land Question." Module Thirty, Activity Three. Exploring Africa, Michigan State University African Studies Center. Archived 2024-04-13.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Mlambo, Alois S. "A History of Zimbabwe." Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- ↑ "A Brief History of South Africa’s Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union (1919-1931)." Dossier #20, The Tricontinental. September 3, 2019. (PDF). Archived 2024-04-21.

- ↑ Kadalie, Clements. "My life and the ICU: The Autobiography of a Black Trade Unionist in South Africa." Frank Cass & Co., Ltd., 1970.

- ↑ Gwisai, Munyaradzi. "Revolutionaries, resistance and crisis in Zimbabwe." Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal. Originally published in Leo Zeilig (ed.), Class Struggle and Resistance in Africa, New Clarion Press, Cheltenham, UK, 2002. Archived 2024-04-21.

- ↑ Chidiebere C Ogbonna "Targeted or Restrictive: Impact of U.S. and EU Sanctions on Education and Healthcare of Zimbabweans." September 2017, African Research Review 11(3):31 DOI:10.4314/afrrev.v11i3.4

- ↑ Tichaona Chifamba, Zhang Yuliang, Cao Kai. "Two-decade-old U.S. sanctions leave Zimbabweans suffering, triggering protests". Xinhua. 2022-07-11. Archived 2022-09-09.

- ↑ George T. Mudimu and Gregory Elich. "The Dynamics of Rural Capitalist Accumulation in Post-Land Reform Zimbabwe." MR Online, June 1, 2023. Archived 2023-04-13.

- ↑ "US plan to discredit Chinese investments unmasked" (2021-09-21). The Herald (Zimbabwe). Retrieved 24/06/2024.

- ↑ Christopher Ojilere (2022-12-29). "Zimbabwe Bans All Lithium Exports" Voice of Nigeria. Archived from the original on 2022-12-30. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Gregory Elich and Sam Moyo. "Reclaiming the Land: Land Reform and Agricultural Development in Zimbabwe: An Interview with Sam Moyo." MR Online, January 02, 2009. Archived 2023-04-13.