More languages

More actions

(Added some info on economy; other minor edits) Tag: Visual edit |

(→Economy: Minor edits and tweaks) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

== Economy == | == Economy == | ||

For decades, Cuba had a Soviet-style planned economy, and like the DPRK, was reluctant to engage in market reforms. However, after the overthrow of the Soviet Union, | For decades, Cuba had a Soviet-style planned economy, and like the DPRK, was reluctant to engage in market reforms. However, after the overthrow of the Soviet Union, the resulting loss of economic aid, and Cuba's relative isolation, made it more vulnerable to the sanctions against it and it became dependent on foreign trade and capital; in the late 2000s and early 2010s, it began implementing market reforms. However, in spite of the market reforms, Cuba's economy is largely centrally-planned, as prices and wages are still set by the government. Despite the economic blockade enforced by the US, Cuba has largely succeeded in providing a decent quality of life for its people and maintaining economic development. As of 2020, Cuba has one of the lowest unemployment rates in the world, of just 1.59%.<ref>[https://www.statista.com/statistics/388644/unemployment-rate-in-cuba/ Cuba: Unemployment rate from 1999 to 2020]. ''Statista''.</ref> Compared to the vast majority of developing countries in [[Latin America]], Africa and southern Asia, Cuba scores extremely well on virtually all indicators of socioeconomic development: life expectancy, access to healthcare and housing, education levels, employment rates, status of women and infant mortality rates.<ref>Clifford L. Staten (2005). 'Cuba and its people' in ''The history of Cuba.'' Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403962591 ([http://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=DE11DAA6342FE92307FDE6B81E5FD1CF Library Genesis link])</ref> | ||

In 2019, the Cuban government began promoting non-agricultural cooperatives to help expand the economy.<ref>[https://en.granma.cu/cuba/2019-09-10/legislation-governing-non-agricultural-cooperatives-updated Legislation governing non-agricultural cooperatives updated] by [[Granma (newspaper)|Granma]], the official newspaper of the [[Communist Party of Cuba]]</ref> | In 2019, the Cuban government began promoting non-agricultural cooperatives to help expand the economy.<ref>[https://en.granma.cu/cuba/2019-09-10/legislation-governing-non-agricultural-cooperatives-updated Legislation governing non-agricultural cooperatives updated] by [[Granma (newspaper)|Granma]], the official newspaper of the [[Communist Party of Cuba]]</ref> | ||

Revision as of 01:07, 3 September 2023

| Republic of Cuba República de Cuba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Capital and largest city | Havana |

| Dominant mode of production | Socialism |

| Government | Marxist–Leninist socialist state |

• First Secretary, President | Miguel Díaz-Canel |

• President of National Assembly of People's Power | Esteban Lazo Hernández |

• President of Council of Ministers | Manuel Marrero Cruz |

| History | |

• Victory of the Cuban Revolution | 1 January 1959 |

| Population | |

• 2019 estimate | 11,193,470 |

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba[a] is a socialist country in North America comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Guided by Marxist–Leninist ideology, Cuba is led by the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC), the vanguard of the Cuban working class.

The Republic of Cuba is one of only five socialist states in the world today (alongside Vietnam, Laos, People's Korea and China). It began as a Soviet-style planned economy, but after the overthrow of the Soviet Union and subsequent loss of influence of the socialist bloc, Cuba became more vulnerable to the United States embargo and dependent of foreign trade and capital. Since then, it has been promoting extensive market reforms.[1]

Cuban healthcare is widely renowned throughout the world, achieving success in virtually every critical area of public health and medicine.[2] Cuba also promotes a healthcare diplomacy by sending doctors to underdeveloped nations which do not have advanced healthcare systems, as well as impressive innovation in biotechnology and pharmaceuticals.[3][4][5]

Cuba's exports around $1.21B mainly of rolled tobacco (23.8%), raw sugar (17.5%), nickel mattes (11%) and hard liquor (8.07%) and its main export partners are China (38.2%), Spain (10.5%), the Netherlands (5.44%) and Germany (5.37%). Cuba imports $5.28B of machinery and appliances (16.7%), electrical machinery and equipment (9.27%) and cereals (7.21%) from Spain (19.2%), China (15%), Italy (6.2%) and Canada (5.4%).[6]

History

Pre-colonization (~3000 BCE – 1492)

The earliest discovered evidence of human activity on the island of Cuba dates back to approximately 4000 B.C., with various other archaeological findings ranging from 3000 to 2000 B.C. The earliest European contact with native inhabitants of Cuba took place when Christopher Columbus raided the easternmost tip of the island in 1492, at first assuming it was an Asian peninsula. Unfortunately, because the Cuban natives either did not use codices or other writing systems, or such evidence was destroyed by the Spanish, all firsthand knowledge of pre-colonial Cuba has been derived from the eyewitness testimony of Columbus and other Spanish colonizers.

According to these accounts, the various tribal communities scattered across the island at the end of the fifteenth century were twenty-nine small, independent chiefdoms; Cuba's principal inhabitants at the time of the Spanish conquest were the Guanajatabey and Taíno peoples, with the latter divided between the Ciboney and so-called “Taíno proper”. The best estimates are that there were between 50,000 and 300,000 indigenous peoples at the time.[7] However, there is an important caveat; in the Caribbean, the genocide of native population was so successful, the relentless destruction of their architecture and culture so complete, that the oldest available sources on the culture of these islands are journals kept by the Spanish invader. As a result, the grandeur, development, cultural complexity and achievements of the civilizations of that region may very well be vastly under-researched, understated, and underestimated.

Out of the three distinct groups, the Guanajatabeyes had arrived the earliest; they are thought to have had inhabited the island of Cuba since at least 2000 BCE, while the Taíno and Ciboney were Arawak tribes that migrated to the Caribbean from the South American mainland and Floridan peninsula, respectively. Guanajatabey society was limited to archaic hunter-gatherer communities no larger than a few hundred individuals, and they lived on seafood, rodents, birds and other small animals, as well as the many wild fruits available in Cuba such as guava and guanabana. They did not live in houses, huts or anything other than natural caves in western Cuba.

The Ciboney, by contrast, were the largest indigenous group of the island. They had migrated in the 1400s from the West Indies, and had 3 class divisions between them; chiefs (caciques), a small middle class that acted as advisers to the chiefs, and commoners. The Ciboney were fishers, hunters and agriculturally advanced enough to cultivate fruits, beans, peanuts, corn and cassava. They lived in straw, palm-thatched houses, with intricate carved furniture and weaved fabrics; they used tobacco in religious ceremonies, and baked cassava and used pepper to preserve meat.[7] After the Spanish occupation, tobacco became an important item for export.[8] At some point, the technologically superior Ciboney had subjugated the Guanajatabeyes, whose tools were largely bone-based.[7]

Spanish colonization (1492–1898)

In the next 70 years after Columbus' arrival in 1492, most of the indigenous peoples on the island were killed, largely due to Spanish systematic genocide, but also due to diseases brought by the Spanish, such as smallpox, typhus, influenza and measles.[7] Spanish colonialism in the Americas was motivated mostly by the Crown's desire for gold, silver and other precious metals. The settlers also had immediate interests for these travels, as they were to receive a share of the exploited value.[9] In 1510, Diego Velázquez, one of the richest settlers in Spain, was in charge of colonizing Cuban territory, beginning the conquest with a prolonged reconnaissance and conquest operation, plagued by bloody incidents. To safeguard trade, Spain decided to organize large fleets that would have the port of Havana as an obligatory stopover point, strategically located at the beginning of the Gulf Stream. Its prime exports were coffee, sugar, and tobacco. The Spanish aristocracy imported many African slaves for this colony.

The Taíno leader Hatuey began a resistance movement against Spain in 1511. The Spanish captured, tortured, and executed him in 1512.[10]

From 1790 to 1820, more African slaves were introduced into Cuba than in the previous century and a half. With a population that in 1841 already exceeded a million and a half inhabitants, the Island harbored a highly polarized society. Between an oligarchy of Creole landowners and Spanish merchants and the slave masses. Slavery was an important source of social instability, not only because of the frequent rebellion by slaves—both individually and in groups—but also because the repudiation of the said institution gave rise to conspiracies with abolitionist purposes, none of which were indigenous-led.

In the 1810s, Cuban slave owners contacted the U.S. consul and tried to join the United States in order to prevent a revolution like in Haiti.[11]

Around 1850 the colony received an influx of lower-class Spanish immigrants, but even they were treated poorly by the aristocracy: sixteen or eighteen-hour workdays, seven days a week, were common, and work conditions in the tobacco industry were rife with poor pay, monotony, and health hazards.

U.S. colonization (1898–1959)

After the Spanish–Statesian War, Spain and the United States signed the Treaty of Paris (1898), by which Spain ceded Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam to the United States for the sum of US $20 million and Cuba became a colony of the United States. In 1901, the USA added the Platt Amendment to the Cuban constitution, allowing the USA to invade Cuba at will and preventing Cuba from making international treaties. It took over 45 square miles of territory at Guantánamo Bay. Sugar production grew from 15% to 70% of total production from 1902 to 1929 as Cuba became a U.S. neocolony.[12]

The United States occupied Cuba from 1906 to 1909, in 1912, and again from 1917 to 1922.[13]:210 It annulled the Platt Amendment in 1934 but continued to occupy Guantánamo Bay.[13]:219

The Popular Socialist Party of Cuba was formed in Havana in 1925. It was later renamed the "Communist Revolutionary Union". In 1961 the party merged into the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations (ORI), the precursor of the current Communist Party of Cuba.

Batista regime (1940–1959)

While the reactionary right-wing dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista reign saw relatively high GDP growth, human development indicators portray dismal social conditions, particularly among the rural peasants. Batista's regime left the majority of the Cuban people mired in poverty and illness, reporting a 91% malnutrition rate among agricultural workers.[14] 20,000 Cubans were killed under Batista's dictatorship.[15]

The mortality rates of the general population was usually high. Poor hygiene, inefficient sanitation and malnutrition contributed to the infant mortality rate of 60 per 1000 lives, maternal mortality rate of 125.3 per 1000, and a life expectancy of 65 years.[16][17] In contrast, Cuba today has an infant mortality rate of 3.8 deaths per 1000 lives as of 2021,[18][19] a maternal mortality rate of 36 per 100,000 live births as of 2017,[20] and a life expectancy of 79 years as of 2021.[21][17]

The rural population in Batista's era suffered from dismal health conditions, having only one rural hospital for the whole island, and only 11% of farm workers drank milk.[22] The infrastructure of households was also extremely underdeveloped under Batista. In a 1953 census, 54% of rural homes had no toilets of any kind. Only 2.3% of rural homes had indoor plumbing, compared with 54.6% of urban homes. In rural areas, 9.1% of houses had electricity, compared with 87% of houses in urban areas. Illiteracy and unemployment were widespread according to the same census, showing that nearly one-quarter of the people 10 years of age and older could not read or write and the unemployment rate was 25%.[14] In 1958, under the Batista dictatorship, half of Cuba's children did not attend school.[23]

Revolutionary movement (1953–1959)

See main article: Cuban Revolution

Due to the inertia and inability to govern of the bourgeois political parties, a movement of a new type was born, headed by Fidel Castro, a young lawyer whose first political activities had developed in the university environment and the ranks of orthodoxy. On July 26, 1953, a crew of revolutionaries, including Fidel Castro, assaulted Fort Moncada but failed. Nonetheless, the Cuban working classes were growing increasingly restless, and consequently, the neocolonial government (headed by Fulgencio Batista) suppressed trade unions, strikes, and censored much of the press. The failed attack inspired the creation of The 26th of July Movement, a Cuban vanguard revolutionary organization and later a political party led by Fidel Castro.

In 1955, Fidel Castro was introduced to Che Guevara. During a long conversation with Fidel on the night of their first meeting, Guevara concluded that the Cuban's cause was the one for which he had been searching and before daybreak, he had signed up as a member of the July 26 Movement.

On 2 December 1956, Fidel Castro and Che Guevara along with 82 men landed in Cuba, having sailed in the boat Granma from Tuxpan, Veracruz, Mexico, ready to organize and lead a revolution. Attacked by Batista's military soon after landing, many of the 82 men were either killed in the attack or executed upon capture; only 22 regrouped in the Sierra Maestra mountain range. While in the Sierra Maestra mountains the guerrilla forces attracted hundreds of Cuban volunteers and won several battles against the Cuban Army. By January of 1959, the Cuban masses had successfully overthrown the neocolonial government and Batista fled to Europe.

The Cuban Revolution was not an explicitly socialist revolution when it began, but was instead a national liberation movement; inspired by Che and his own brother Raúl, Fidel Castro announced he was a Marxist–Leninist in 1961, and that the Cuban revolution was now a socialist revolution that adhered to Marxist–Leninist ideology.

Socialism (1959–present)

The republic era of Cuba began after the Cuban Revolution successfully took power. Shortly after the victory of the revolution, Cuba carried out a profound agrarian reform which ended latifundia [a highly unequal land estate system] in the island and distributed land to thousands of formerly landless small farmers. Initiatives in the cities were also made. Urban reform brought a halving of rents for Cuban tenants, opportunities for tenants to own their housing, and an ambitious program of housing construction for those living in marginal shantytowns. New housing, along with the implementation of measures to create jobs and reduce unemployment, especially among women, rapidly transformed the former shantytowns.[24]

In 1960, Anastas Mikoyan visited Cuba, and the Soviet Union agreed to buy sugar from Cuba. The Soviet Union gave over $100 million to Cuba to build its chemical industry. Overall, the Soviet Union gave over $600 million to Cuba in addition to hundreds of millions more from Eastern Europe and a $60 million loan with 0% interest from China. The USSR trained over 3,000 Cubans in agricultural science and mechanization and 900 engineers and technicians.[25]

In 1961, the CIA sent Cuban exiles to attempt a counterrevolution against Castro. They killed over 2,000 Cubans but were defeated and the revolution survived. After the invasion failed, they enacted Operation Mongoose and secretly performed terrorist attacks against civilians in an attempt to destabilize Cuba. In 1976, reactionary Cuban exiles bombed Cubana de Aviación Flight 455, killing everyone on board.[26]

The Cuban revolution has also made great strides in eliminating discrimination and inequality. In the last 40 years Cubans have greatly reduced differences in income between the lowest and the highest paid persons. Women have benefited significantly from the revolution as they have educated themselves and entered the labor force in large numbers. The differences among Cubans of different races have also been reduced.[24]

Fidel Castro became First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba in 1961. He was replaced in 2011 by his brother Raúl Castro. Miguel Díaz-Canel replaced Raúl in 2021.

In 2021, anti-communist and pro-imperialist protestors took to the streets with support from US entities including the CIA.[27]

Economy

For decades, Cuba had a Soviet-style planned economy, and like the DPRK, was reluctant to engage in market reforms. However, after the overthrow of the Soviet Union, the resulting loss of economic aid, and Cuba's relative isolation, made it more vulnerable to the sanctions against it and it became dependent on foreign trade and capital; in the late 2000s and early 2010s, it began implementing market reforms. However, in spite of the market reforms, Cuba's economy is largely centrally-planned, as prices and wages are still set by the government. Despite the economic blockade enforced by the US, Cuba has largely succeeded in providing a decent quality of life for its people and maintaining economic development. As of 2020, Cuba has one of the lowest unemployment rates in the world, of just 1.59%.[28] Compared to the vast majority of developing countries in Latin America, Africa and southern Asia, Cuba scores extremely well on virtually all indicators of socioeconomic development: life expectancy, access to healthcare and housing, education levels, employment rates, status of women and infant mortality rates.[29]

In 2019, the Cuban government began promoting non-agricultural cooperatives to help expand the economy.[30]

Exports

Cuba exports a total of $1.21 billion as of 2019. Its exports are composed of rolled tobacco ($287M), raw sugar ($211M), nickel mattes ($134M), hard liquor ($97.3M), and zinc ore ($78.4M). The most common export destinations are China ($461M), Spain ($127M), Netherlands ($65.5M), Germany ($64.7M), and Cyprus ($48.9M).[6]

Imports

Cuba imports a total of $5.28 billion as of 2019. Its imports are composed of machinery and appliances ($884M), poultry meat ($286M), wheat ($181M), soybean meal ($167M), corn ($146M), and concentrated milk ($136M). The most common import partners for Cuba are Spain ($1.01B), China ($790M), Italy ($327M), Canada ($285M), and Russia ($285M).[6] The Cuban economy is heavily reliant on food imports, with 70% to 80% of its food requirement being imported from outside.[31]

Sustainable development and environmental preservation

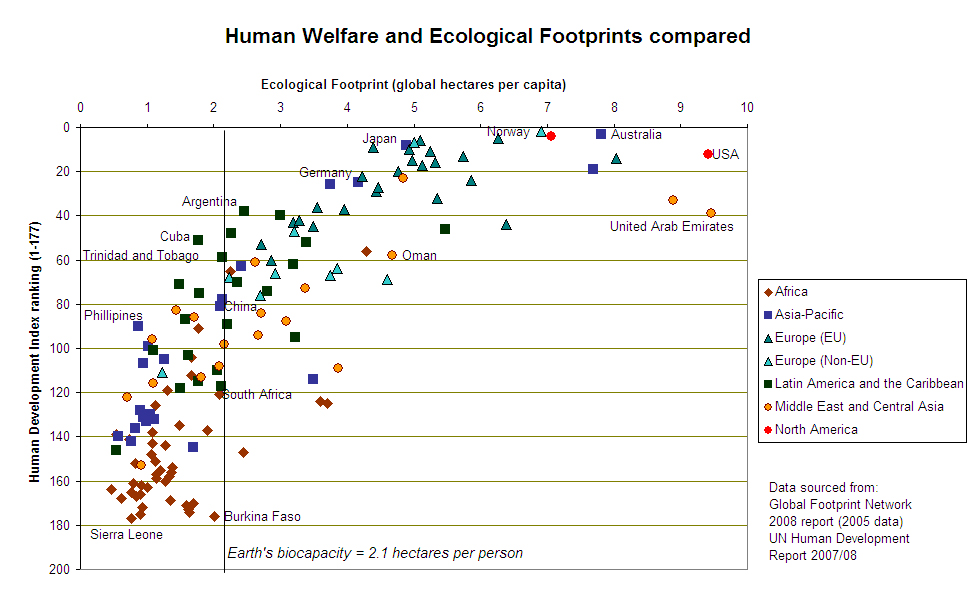

Cuba is the most sustainably developed country worldwide, achieving high levels of social performance with low levels of ecological impact.[32][33][34]

Politics

In the constitution of Cuba, the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC) is the "superior leading political force of society and the state",[35] and its role is fundamental in setting the country's national policy, but it shares power with several other state organs:

- National Assembly of People's Power (NAPP),[b] considered the maximum authority of the state, mainly exercises legislative functions.[36]

The National Assembly of People's Power is the supreme organ of State power. It represents and expresses the sovereign will of all the people. It is the only body with constituent and legislative power in the Republic. It is made up of deputies elected by the free, direct and secret vote of the voters, in the proportion and according to the procedure determined by law.

It is elected for a five-year term. This term may only be extended by agreement of the Assembly itself in case of war or by virtue of other exceptional circumstances that prevent the normal holding of the elections and while such circumstances subsist.

When constituting itself for a new legislature, it elects its President, Vice President and Secretary from among its deputies. The law regulates the form and procedure by which the Assembly is constituted and carries out that election. The National Assembly of People's Power elects, from among its deputies, the Council of State, made up of a President, a First Vice President, five Vice Presidents, a Secretary and twenty-three other members. The President of the Council of State is head of state and head of government.

The Council of State is responsible to the National Assembly of People's Power and renders an account of all its activities. Local Bodies of Popular Power The Assemblies of Popular Power, constituted in the political-administrative demarcations into which the national territory is divided, are the local superior bodies of State power, and, consequently, are invested with the highest authority for the exercise of state functions in their respective demarcations and for this, within the framework of their competence, and adjusting to the law, they exercise government. In addition, they contribute to the development of activities and compliance with the plans of the units established in their territory that are not subordinate to them, in accordance with the provisions of the law. The Local Administrations that these Assemblies constitute, direct the economic, production and service entities of local subordination, with the purpose of satisfying the economic, health and other welfare, educational, cultural, sports and recreational needs of the community of the territory to which the jurisdiction of each extends. For the exercise of their functions, the Local Assemblies of People's Power rely on the People's Councils and on the initiative and broad participation of the population, and they act in close coordination with the mass and social organizations.

The Popular Councils are constituted in cities, towns, neighborhoods, and rural areas; they are invested with the highest authority for the performance of their duties; they represent the demarcation where they operate and at the same time are representatives of the municipal, provincial and national bodies of Popular Power. They actively work for efficiency in the development of production and service activities and for the satisfaction of the welfare, economic, educational, cultural and social needs of the population, promoting their greater participation and local initiatives to solve problems. their problems. They coordinate the actions of existing entities in their area of action, promote cooperation between them and exercise control and supervision of their activities. The Popular Councils are constituted from the delegates elected in the circumscriptions, who must choose among themselves who presides over them. The representatives of the mass organizations and the most important institutions in the demarcation can belong to them.

- Council of State,[c] an organ of the National Assembly which implements the decisions of NAPP and exercises control and oversight of state organs.[37]

The Council of State is the body of the National Assembly of People's Power that represents it between one session and another, executes its agreements and fulfills the other functions that the Constitution attributes to it. It has a collegial character and, for national and international purposes, holds the supreme representation of the Cuban State. All the decisions of the Council of State are adopted by the favorable vote of the simple majority of its members. The mandate entrusted to the Council of State by the National Assembly of People's Power expires when the new Council of State elected by virtue of its periodic renewals takes office.

- Council of Ministers,[d] exercises the executive functions and directs political, economical, cultural, scientific and social activities based on the decisions of the NAPP.[38]

The Council of Ministers is the highest executive and administrative body and constitutes the Government of the Republic. The number, name and functions of the central ministries and agencies that are part of the Council of Ministers is determined by law. It is made up of the Head of State and Government, who is its President, the First Vice President, the Vice Presidents, the Ministers, the Secretary and the other members determined by law. The President, the First Vice President, the Vice Presidents and other members of the Council of Ministers determined by the President, make up its Executive Committee. The Executive Committee can decide on the issues attributed to the Council of Ministers, during the periods that mediate between one and another of its meetings. The law regulates the organization and functioning of the Council of Ministers. The Council of Ministers is responsible and renders an account, periodically, of all its activities before the National Assembly of People's Power.

- National Defense Council,[e] is constituted and prepared since peacetime to lead the country in the conditions of a state of war, during war, general mobilization or a state of emergency.[39]

Elections

Elections in Cuba take place at three levels: municipal, provincial and national. There are also two types of elections: general and partial. All citizens and permanent residents sixteen years and older are allowed to vote, without any registration or effort on the part of the citizens. In order to make elections fair, candidates cannot spend money on their campaigns.[40] The PCC is not involved in either nominating or electing candidates,[41] and party membership is not required to run for office. The most recent elections had a voter turnout rate of 73%, and elections are always held on weekends so people do not have to choose between work and voting. Each municipality must have at least two candidates running for election so no one runs unopposed. If no candidate wins a majority, a runoff occurs the following week.[40]

Nominations

The Committees in Defense of the Revolution, with more than 8.4 million members, and the the Cuban Federation of Women, which includes more than 85% of Cuban women 15 and older, nominate candidates for elections.[40]

Partial elections

The partial elections happen every two and a half years at the municipal level.[42] Through the neighborhood constituencies, neighbors directly nominate people from among themselves by show-of-hands, and from among these nominees, citizens elect delegates to the Municipal Assembly of People's Power via secret ballot.[41]

Governance

Education

Cuba has a public education system from the primary to the superior levels, free to its citizens. Around 12% of Cuba's GDP is invested in public education, the highest percentage on GDP devoted to education worldwide.[43] The literacy rate of the adult population is 99.75%, the highest in Latin America.[44] One of the most significant developments in Cuban education was the National Literacy Campaign of 1961, spearheaded by Che Guevara, a campaign recognized as one of the most successful initiatives of its kind, which mobilized teachers, workers, and secondary school students to teach more than 700,000 persons how to read. This campaign reduced the illiteracy rate from 23% to 4% in the space of one year.[24]

Healthcare

Cuba's healthcare system is based on public investment and universal provision. Around 11% of its GDP is devoted to healthcare, the highest among Latin American countries.[45] As a result of this, free healthcare is guaranteed for all citizens, and Cuba's health indicators are highly ranked both regionally and globally.[14] Besides the investment, another important factor of success in Cuban healthcare model is its strategy.[46] Cuban doctors focus on preventative medicine to prevent disease before it occurs.[47] Cuban medicine has made some impressive achievements, such as eliminating mother-to-child HIV and syphilis transmission[4] and creating a vaccine for lung cancer.[48]

In 2008, Cuba authorized free sex reassignment surgery for transgender people.[49]

In the Cuban capitol city of Havana, the Latin American School of Medicine offers free tuition, accommodation, and board. Some Statesian students attend this school.[50]

Nutrition

With a rate of undernourishment of only 2.5%,[51] Cuba is one of only 17 nations worldwide to have a score lower than 5 on the Global Hunger Index.[52] Statesians are more than twice as likely to die from malnutrition than Cubans.[53]

Over the last 50 years, comprehensive social protection programs have largely eradicated poverty and hunger. Food-based social safety nets include a monthly food basket for the entire population, school feeding programs, and mother-and-child health care programs.[31] The average Cuban consumes approx. 3300 calories per day, far above the Latin American and Caribbean average. Approx. 2/3 of nutritional needs are met by monthly food rations, while the rest is bought independently.[54]

Common misconceptions

Cuban "exiles" to the USA

A common anti-communist trope against Cuban socialism is the question of Cuban immigrants who depart to the US. Socialism in Cuba is portrayed as a dystopia which fuels migrants to look for an alternative in the United States. The first wave of migrants happened in 1959 to 1962, just after the Cuban Revolution, motivated by the political turmoil in the island. The vast majority of these migrants were allies of the Batista dictatorship, including military officers, large landowners or wealthy business owners who lost their property in the island,[55] prompting the bourgeois media to dub it as the "Golden exile." The second wave of migrants happened from 1965 to 1973, and the migrants still over-represented the wealthy sections population. Together, these two migrant waves represent over 51% of all population migrated from Cuba to the United States.[55]

The exile narrative also omits the fact that there is a circular migration and return of many of the migrated. The "exile" narrative is a remnant of the Cold War era, a propaganda narrative used to belittle and distort the Cuban reality.[56] Besides the political motivation behind the first waves of migration, since the 90's there is an economic reason behind the migration waves, mainly related to the blockade promoted by the US and the overthrow of the Soviet Union, which affected immensely the Cuban economy.

References

- ↑ Communist Party of Cuba (1997). Economical resolution of the 5th Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba (Spanish: Resolución económica V Congreso del Partido Comunista de Cuba). [PDF]

- ↑ Carol Lynn Esposito (2018). Against all odds: Cuba achieves healthcare for all – An analysis of Cuban healthcare. The Journal of the New York State Nurses' Association, volume 45, number 1. (PDF link to journal)

- ↑ John M. Kirk (2015). Healthcare without borders: Understanding Cuban medical internationalism. University Press of Florida. (Library Genesis link)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 World Health Organization (2015). WHO validates elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis in Cuba.

- ↑ Alexandra Sifferlin (2014). Why Cuba is so good at fighting ebola. Time Magazine.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Cuba exports, imports and trade partners" (2019). The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Clifford L. Staten (2005). 'Early Cuba: Colonialism, Sugar and Nationalism: Cuba to 1868' in The history of Cuba. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403962591 (Library Genesis link)

- ↑ Rex A Hudson (2002). 'Historical setting', in Cuba: a country study. Washington, DC: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 0844410454 (Library Genesis link)

- ↑ Eric Williams (1984). 'Gold and sugar' in From Columbus to Castro; The History of the Caribbean, 1492–1969. London: A. Deutsch. ISBN 0233000909 (Library Genesis link)

- ↑ Nick Estes, et al. (2021). Red Nation Rising: 'Anti-Indianism' (p. 30). [PDF]

- ↑ Domenico Losurdo (2011). Liberalism: A Counter-History: 'Crisis of the English and American Models' (p. 152). [PDF] Verso. ISBN 9781844676934 [LG]

- ↑ David Vine (2020). The United States of War: 'Going Global' (pp. 191–3). Oakland: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520972070 [LG]

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 David Vine (2020). The United States of War: 'The Military Opens Doors'. Oakland: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520972070 [LG]

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Andrea Carter (2013). Cuba's food-rationing system and alternatives. Cornell University. (PDF link)

- ↑ Elio Delgado Legon (2017-01-26). "Massacres during Batista’s Dictatorship" Havana Times. Archived from the original on 2022-01-26. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- ↑ LA Binn (2013). Cuba: healthcare and the revolution. West Indian Medical Journal.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 The World Bank. Life expectancy at birth, total (years) - Cuba.

- ↑ Macotrends. Cuba infant mortality rate 1950-2021

- ↑ The World Bank. Mortality rate, infant (per 1,000 live births) - Cuba.

- ↑ Macrotrends. Cuba maternal mortality rate 2000-2021

- ↑ Macrotrends. Cuba life expectancy 1950-2021

- ↑ C. William Keck, Gail A. Reed (2012). The curious case of Cuba. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300822 [HUB]

- ↑ Jonathan Glennie. “Cuba: A development model that proved the doubters wrong”. The Guardian, 5 August 2011.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Oxfam (2002). Cuba: social policy at the crossroads. (PDF link)

- ↑ Vijay Prashad (2017). Red Star over the Third World: 'Colonial Fascism' (pp. 110–113). [PDF] New Delhi: LeftWord Books.

- ↑ Peter Kornbluh (2005). LUIS POSADA CARRILES: THE DECLASSIFIED RECORD.

- ↑ https://www.cubasupport.ie/latest/the-cia-insists-on-promoting-a-color-revolution-in-cuba/

- ↑ Cuba: Unemployment rate from 1999 to 2020. Statista.

- ↑ Clifford L. Staten (2005). 'Cuba and its people' in The history of Cuba. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403962591 (Library Genesis link)

- ↑ Legislation governing non-agricultural cooperatives updated by Granma, the official newspaper of the Communist Party of Cuba

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 United Nations World Food Program. Cuba.

- ↑ Jason Hickel (2019). The sustainable development index: Measuring the ecological efficiency of human development in the anthropocene. Ecological Economics. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.05.011 [HUB]

- ↑ World Wildlife Fund. The Other Cuban Revolution.

- ↑ As world burns, Cuba number 1 for sustainable development: WWF. Telesur.

- ↑ 2019 Constitution of Republic of Cuba. Article 5. Link (Spanish)

- ↑ 2019 Constitution of Republic of Cuba. Articles 102 & 103. Link (Spanish)

- ↑ 2019 Constitution of Republic of Cuba. Article 120–122. Link (Spanish)

- ↑ 2019 Constitution of Republic of Cuba. Articles 133–137. Link (Spanish)

- ↑ 2019 Constitution of Republic of Cuba. Articles 218–219. Link (Spanish)

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Calla Walsh (2022-12-02). "US youth observe Cuba’s elections – and learn about real democracy" Multipolarista. Archived from the original on 2022-12-04. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Arnold August (2013). Cuba and its neighbours: democracy in motion: 'Elections in contemporary Cuba'. [LG]

- ↑ "How do elections work in Cuba?" (2018-02-20). Granma.

- ↑ World Bank (2010). Cuba – Government expenditure on education, total (% of GDP).

- ↑ World Bank (2012). Cuba – Literacy rate, adult total (% of people ages 15 and above).

- ↑ Richard S. Cooper, Joan F Kennelly, Pedro Orduñez-Garcia (2006). Health in Cuba. International Journal of Epidemiology. doi:10.1093/ije/dyl175 [HUB]

- ↑ Richard S. Cooper, Joan F Kennelly, Pedro Orduñez-Garcia (2006). Health in Cuba. International Journal of Epidemiology. doi:10.1093/ije/dyl175 [HUB]

- ↑ Jack Guy (2017-11-29). "Why Cuba Has the Best Doctors in the World" Culture Trip. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ↑ Sarah Zhang (2016-11-07). "Cuba's Innovative Cancer Vaccine Is Finally Coming to America" The Atlantic. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ↑ "Cuba to provide free sex-change" (2008-06-07). BBC. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ↑ "Meet the U.S. Students Studying Medicine For Free in Cuba" (2022-02-02). Breakthrough News.

- ↑ World Bank (2018). Cuba – Prevalence of undernourishment (% of population).

- ↑ Global Hunger Index (2020. Cuba.

- ↑ Our World in Data (2017). Death rate from malnutrition, 1990 to 2017 (Cuba and United States).

- ↑ FAS, USDA (2008). Cuba’s food & agriculture situation report. (PDF link)

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Jorge Duany (1999). Cuban communities in the United States: migration waves, settlement patterns and socioeconomic diversity. Pouvoirs dans la Caraïbe.

- ↑ Katarzyna Dembicz (2020). The end of the myth of the Cuban exile? Current trends in Cuban emigration. [PDF] International Studies. Interdisciplinary Political and Cultural Journal. Vol. 25, No. 1/2020.