More languages

More actions

Verda.Majo (talk | contribs) (→Indo-Pacific: added info about Diego Garcia) Tag: Visual edit |

Verda.Majo (talk | contribs) (filled out "war provocations", will edit this section again shortly) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

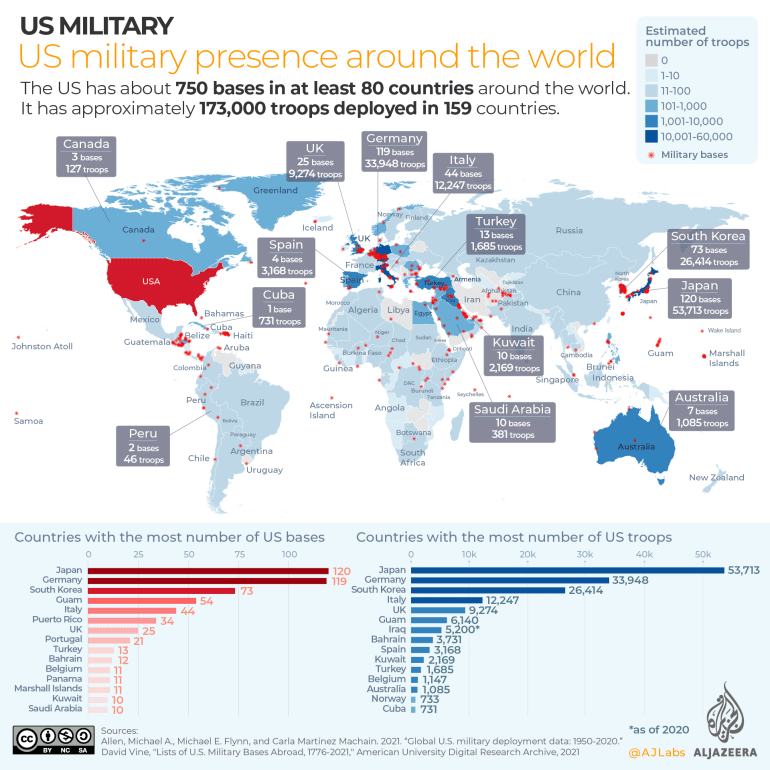

[[File:US military bases.png|thumb|Map of U.S. military bases and troops deployed abroad.]] | [[File:US military bases.png|thumb|Map of U.S. military bases and troops deployed abroad.]] | ||

'''Anti-base movement''' is a term<ref>{{Citation|author=David Vine|year=2019|title=No Bases? Assessing the Impact of Social Movements Challenging US Foreign Military Bases|title-url=https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/701042|quote=I use the term “antibase movement” because it is widely used by movement members and scholars and because such movements, strictly speaking, are “anti-” in the sense that they are opposed to some aspect of the life of a base or its personnel.|pdf=https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/701042|publisher=Current Anthropology|volume=Volume 60, Number S19}}</ref> which refers to various movements which focus on opposing aspects of military bases, which can range from opposition to specific activities of bases or base personnel, to opposing their presence or construction in particular locations, to opposing their existence in general. It can also refer to these movements collectively.<ref>Yeo, Andrew. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/27735112 "Not in Anyone's Backyard: The Emergence and Identity of a Transnational Anti-Base Network."] International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 53, No. 3 (Sep., 2009), pp. 571-594. Oxford University Press.</ref> | '''Anti-base movement''' is a term<ref name=":8">{{Citation|author=David Vine|year=2019|title=No Bases? Assessing the Impact of Social Movements Challenging US Foreign Military Bases|title-url=https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/701042|quote=I use the term “antibase movement” because it is widely used by movement members and scholars and because such movements, strictly speaking, are “anti-” in the sense that they are opposed to some aspect of the life of a base or its personnel.|pdf=https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/701042|publisher=Current Anthropology|volume=Volume 60, Number S19}}</ref> which refers to various movements which focus on opposing aspects of military bases, which can range from opposition to specific activities of bases or base personnel, to opposing their presence or construction in particular locations, to opposing their existence in general. It can also refer to these movements collectively.<ref>Yeo, Andrew. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/27735112 "Not in Anyone's Backyard: The Emergence and Identity of a Transnational Anti-Base Network."] International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 53, No. 3 (Sep., 2009), pp. 571-594. Oxford University Press.</ref> | ||

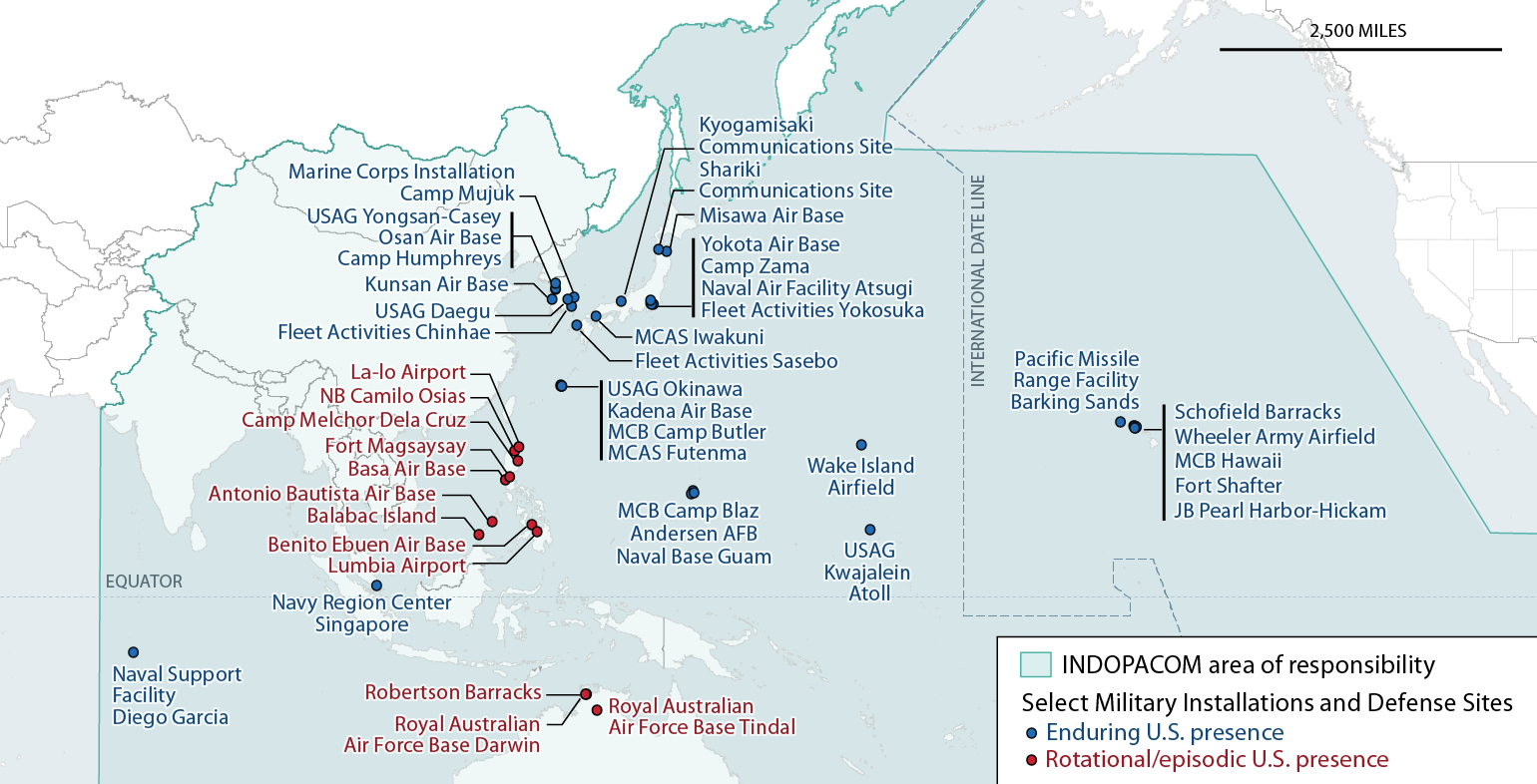

Given that the majority of foreign military bases around the world are [[United States of America|United States]] bases,<ref>David Vine, Patterson Deppen and Leah Bolger. [https://quincyinst.org/research/drawdown-improving-u-s-and-global-security-through-military-base-closures-abroad/ "Drawdown: Improving U.S. and Global Security Through Military Base Closures Abroad."] Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, September 20, 2021. [https://web.archive.org/web/20240312130118/https://quincyinst.org/research/drawdown-improving-u-s-and-global-security-through-military-base-closures-abroad/ Archived] 2024-03-12.</ref><ref>Jawad, Ashar. [https://www.insidermonkey.com/blog/5-countries-with-the-most-overseas-military-bases-1237758/5/ "5 Countries With the Most Overseas Military Bases."] Insider Monkey, December 15, 2023.</ref><ref>[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=amusB9j7Oz4 "Why 90% Of Foreign Military Bases Are American."] AJ+ on YouTube, Jan 13, 2022.</ref> many anti-base movements around the world have been directed at U.S. bases. | Given that the majority of foreign military bases around the world are [[United States of America|United States]] bases,<ref>David Vine, Patterson Deppen and Leah Bolger. [https://quincyinst.org/research/drawdown-improving-u-s-and-global-security-through-military-base-closures-abroad/ "Drawdown: Improving U.S. and Global Security Through Military Base Closures Abroad."] Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, September 20, 2021. [https://web.archive.org/web/20240312130118/https://quincyinst.org/research/drawdown-improving-u-s-and-global-security-through-military-base-closures-abroad/ Archived] 2024-03-12.</ref><ref>Jawad, Ashar. [https://www.insidermonkey.com/blog/5-countries-with-the-most-overseas-military-bases-1237758/5/ "5 Countries With the Most Overseas Military Bases."] Insider Monkey, December 15, 2023.</ref><ref>[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=amusB9j7Oz4 "Why 90% Of Foreign Military Bases Are American."] AJ+ on YouTube, Jan 13, 2022.</ref> many anti-base movements around the world have been directed at U.S. bases. | ||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

=== War provocations === | === War provocations === | ||

The presence of military bases in a location leads to the concern of that location becoming a strategically significant location with regard to international tensions involving the host country, the hosted country, and their various neighbors, allies, targets, and/or rivals. People who live in the host nation are confronted with the potential wartime actions resulting from the presence of a base in their territory in addition to the peacetime concern of the base's domestic impact as well as its international potential to provoke tensions. Given these considerations, individuals and organizations within anti-base movements may exhibit a variety of perspectives on such issues, ranging from locals' urgent concerns over their location becoming a diplomatic pawn or wartime hotspot, general [[Anti-war movement|anti-war]] or [[Pacifism|pacifist]] sentiments, promotion of [[Non-Aligned Movement|non-alignment]], to explicitly [[Anti-imperialism|anti-imperialist]] sentiment.<ref name=":8" /> | |||

== | == Bases and anti-base movements by location == | ||

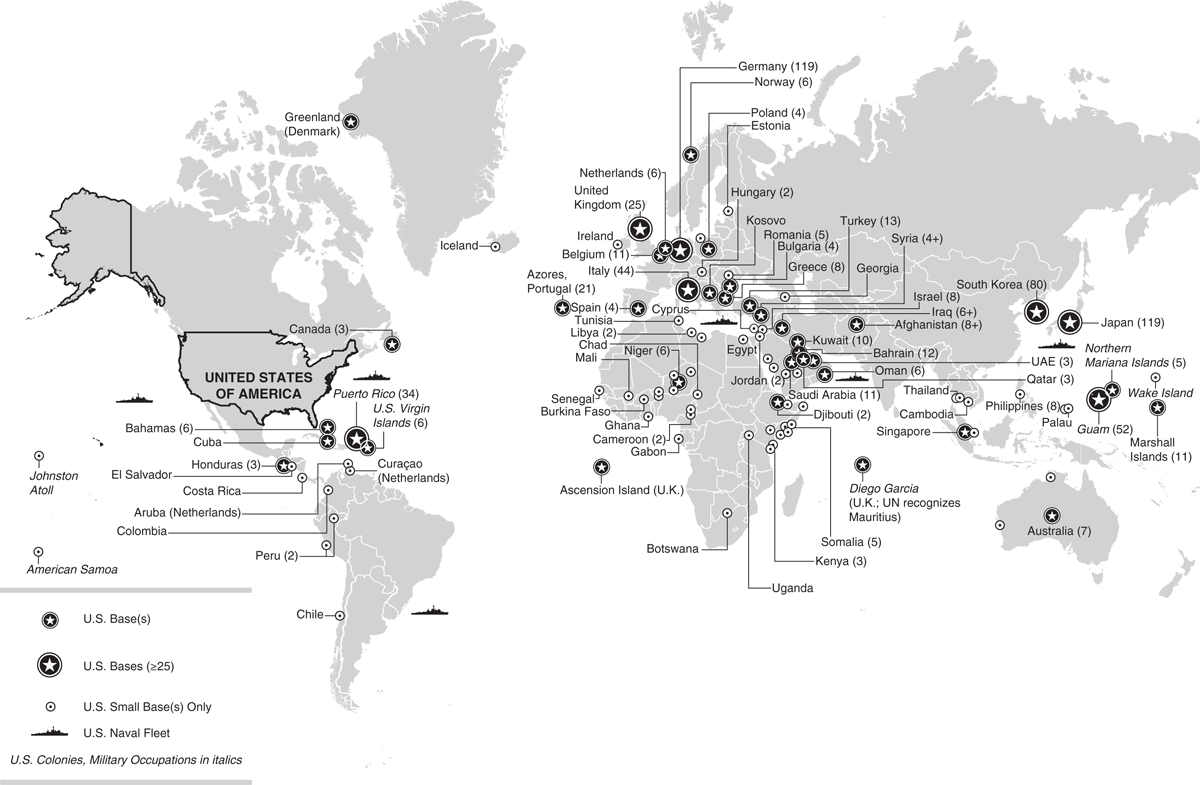

[[File:US Combatant Commands.png|alt= A world map divided by US combatant command, generally corresponding to major continents and regions. Includes USNORTHCOM (North America), USSOUTHCOM (South America), USEUCOM (Europe), USAFRICOM (Africa), USCENTCOM (Middle East), USINDOPACOM (Indo-Pacific).|thumb|Areas of responsibility of US combatant commands.]] | [[File:US Combatant Commands.png|alt= A world map divided by US combatant command, generally corresponding to major continents and regions. Includes USNORTHCOM (North America), USSOUTHCOM (South America), USEUCOM (Europe), USAFRICOM (Africa), USCENTCOM (Middle East), USINDOPACOM (Indo-Pacific).|thumb|Areas of responsibility of US combatant commands.]] | ||

The [[United States Department of Defense]] (DOD) divides its commands into various areas of responsibility (AOR), with seven combatant commands covering geographic areas (one of them being US Space Command), while the remaining commands cover functions such as transportation and special operations.<ref>[https://usafa.libguides.com/combatantcommands/overview “USAFA Library Guides: Combatant Commands: Combatant Command Overview.”] U.S. Air Force Academy.</ref><ref>[https://www.defense.gov/About/combatant-commands/ "Combatant Commands."] U.S. Department of Defense. [https://web.archive.org/web/20240415020523/https://www.defense.gov/About/Combatant-Commands/ Archived] 2023-04-15.</ref> As US bases are generally managed and strategically conceptualized according to this structure, and likewise anti-base movements in different nations are thus strategically linked and affected by which areas of responsibility they fall under or adjoin, this section will be divided roughly following its scheme and some of its terminology. | The [[United States Department of Defense]] (DOD) divides its commands into various areas of responsibility (AOR), with seven combatant commands covering geographic areas (one of them being US Space Command), while the remaining commands cover functions such as transportation and special operations.<ref>[https://usafa.libguides.com/combatantcommands/overview “USAFA Library Guides: Combatant Commands: Combatant Command Overview.”] U.S. Air Force Academy.</ref><ref>[https://www.defense.gov/About/combatant-commands/ "Combatant Commands."] U.S. Department of Defense. [https://web.archive.org/web/20240415020523/https://www.defense.gov/About/Combatant-Commands/ Archived] 2023-04-15.</ref> As US bases are generally managed and strategically conceptualized according to this structure, and likewise anti-base movements in different nations are thus strategically linked and affected by which areas of responsibility they fall under or adjoin, this section will be divided roughly following its scheme and some of its terminology. | ||

Revision as of 13:02, 16 April 2024

Anti-base movement is a term[1] which refers to various movements which focus on opposing aspects of military bases, which can range from opposition to specific activities of bases or base personnel, to opposing their presence or construction in particular locations, to opposing their existence in general. It can also refer to these movements collectively.[2]

Given that the majority of foreign military bases around the world are United States bases,[3][4][5] many anti-base movements around the world have been directed at U.S. bases.

Among the many grievances expressed by anti-base movement activists are issues such as criminal and negligent activity of base personnel, the environmental pollution and destruction generated by U.S. bases, the erosion of national sovereignty that occurs with the U.S. military presence in host locations, and the international provocations and tensions that occur when countries host US bases and collaborate with US military exercises (such as the biennial US-led RIMPAC exercises).[6]

Prevalence of US bases

As of a 2021 estimate, the U.S. has approximately 750 bases around the world in at least 80 countries, with the largest concentration of them being in Japan (especially in Okinawa), followed by Germany and south Korea,[7] resulting in many corresponding anti-base movements. There are also anti-base movements within locations claimed by the U.S. as its own territory, some examples being Guam and Hawaiʻi.[8][9]

Additionally, some anti-base movements oppose bases which are not formally considered to be a US base by law, but which effectively serve as a US base. An example of this would be the Military-Civilian Port Complex in south Korea, technically a south Korean base, but which local activists have explained is a place where "strategic assets in the US military can stop by whenever they please according to American interests."[10]

Another example of a legally ambiguous de facto base is the West Africa Logistics Network (WALN) at Kotoka International Airport in Ghana, a "cooperative security location" where the US military and related personnel are afforded numerous privileges, including the ability to conduct construction activities and store defense equipment, supplies, and materiel, enter into Ghana without visa or passport nor customs inspection for U.S. personnel, and protection for U.S. soldiers from being prosecuted by Ghanaian authorities for crimes, following a 2018 Status of Forces Agreement.[11][12]

Issues with US bases

Violence toward local population

The violent crimes of U.S. military personnel and U.S. civilian contractors working in base areas include numerous killings and sexual assault crimes committed against the citizens of the countries where they are stationed.[13]

In addition to violence perpetrated by individual personnel against locals, negligence during routine activities of bases have also caused violent damage to local populations, such as people being seriously injured and killed by errant bombs.[14]

Areas with a base presence also face issues of increased sex trafficking. For example, in south Korea, a legally-sanctioned prostitution industry was purposely encouraged and maintained by the government in special zones around US bases, with this system persisting for decades.[15]

Environmental destruction

The environmental destruction brought about by base presence takes a range of forms, arising from the initial construction of the base and how it alters the environment, to the ongoing activities of the base in that particular location, to the after-effects that remain even after a base has ceased operation. Some examples of environmental hazards are leakages of jet fuel into local drinking water, toxic PFAS foam leaks, litter from practice drills bleeding chemicals into the ground and water, and extreme noise pollution. In addition to physically hazardous pollution, culturally or spiritually significant sites can be destroyed or desecrated by base presence. A 2018 petition by World Can't Wait to stop RIMPAC exercises, addressed to the then-governor of Hawaiʻi, describes further examples:

Retired military ships are towed out to sea and then targeted with missiles and torpedoes until they sink to a watery graveyard on the ocean floor. There they leach toxic chemicals, including PCBs, which accumulate in the bodies of fish, dolphins and whales – and ultimately into our food. Amphibious landing exercises, which include heavy tracked vehicles, damage reefs, erode shoreline, and endanger wildlife. [...] Areas that have been used for live fire training and bombing practice are uninhabitable; bombing and live fire practice is not only continuing but escalating in the age of the “Pacific Pivot”. Indigenous Hawaiian cultural sites have been destroyed. U.S. Military fuel storage tanks are leaking poisons into the drinking water in Hawai`i's most populous city. Vast areas of land and water are so toxic as to be unusable.[16]

National sovereignty concerns

Bases may be established and their continuing presence maintained by a variety of methods, ranging from mutual legal agreements to brute force and occupation. Often, a combination of these factors is employed in installing and maintaining a base's presence when its presence is based in imperialist, bourgeois interests not premised on local popular support or when local popular support diminishes and wavers over time.

The presence of foreign bases in one's territory raises concerns over the effect the base presence has on national sovereignty in the host (or occupied) nation. This may range from issues such as which nation has authority to prosecute crimes committed by base personnel in the host country, to what the land area, local resources, and local labor consumed by the base could be otherwise used for by the host nation's populace, to the potential consequences that large concentrations of foreign military personnel and their equipment being present in the location may have on the host nation's overall national security, domestic policymaking, and diplomatic bargaining power.[17]

Status of Forces Agreements

The legal agreements made between countries to host foreign military personnel and how domestic laws apply to them are commonly known as Status of Forces Agreements (SOFAs). There is no standard form of SOFA and they may include a variety of provisions. In the case of SOFAs made with the U.S., the most commonly addressed issue in a SOFA is legal protection from prosecution for U.S. personnel while present in a foreign country, and whether the U.S. will exercise sole jurisdiction over U.S. personnel or shared jurisdiction with the host. SOFAs are not themselves security arrangements nor basing agreements. As is noted by a Congressional Research Service report, "a SOFA itself does not constitute a security arrangement; rather, it establishes the rights and privileges of U.S. personnel present in a country in support of the larger security arrangement." The 2012 report noted that, at time of writing, the U.S. was party to more than 100 agreements that may be considered SOFAs.[18]

Though SOFAs are not formally basing agreements, a 2021 article in The Tricontinental explains how Ghana's 2018 SOFA agreement nonetheless allows the U.S. such a level of authority over facilities in Ghana so as to be able to effectively set up a base through Articles 5 and 6 of the agreement, designating agreed facilities to be of "unimpeded" and "exclusive" use to the U.S. and that Ghana "shall also provide access to and use of a runway that meets the requirements of United States forces."[12] Furthermore, the agreement gives the U.S. forces and U.S. contractors the ability to "undertake construction activities" and make alterations to agreed facilities and to "preposition and store defense equipment, supplies, and materiel" at agreed facilities and areas,[19] gives U.S. soldiers the right to carry arms on duty, allows U.S. army and civilians to enter Ghana without a passport nor a visa but just identification cards, allows the U.S. army to not take responsibility for the death of any other person aside from U.S. military personnel, and third party issues involving U.S. military personnel will only be resolved according to the laws of the United States, among other preferential treatments.[19][20][11] Such agreements between the U.S. and Ghana have led to the establishment of the West Africa Logistics Network (WALN) at Kotoka International Airport in Accra to "ferry supplies and arms to special forces troops across the region".[21]

Occupation

War provocations

The presence of military bases in a location leads to the concern of that location becoming a strategically significant location with regard to international tensions involving the host country, the hosted country, and their various neighbors, allies, targets, and/or rivals. People who live in the host nation are confronted with the potential wartime actions resulting from the presence of a base in their territory in addition to the peacetime concern of the base's domestic impact as well as its international potential to provoke tensions. Given these considerations, individuals and organizations within anti-base movements may exhibit a variety of perspectives on such issues, ranging from locals' urgent concerns over their location becoming a diplomatic pawn or wartime hotspot, general anti-war or pacifist sentiments, promotion of non-alignment, to explicitly anti-imperialist sentiment.[1]

Bases and anti-base movements by location

The United States Department of Defense (DOD) divides its commands into various areas of responsibility (AOR), with seven combatant commands covering geographic areas (one of them being US Space Command), while the remaining commands cover functions such as transportation and special operations.[22][23] As US bases are generally managed and strategically conceptualized according to this structure, and likewise anti-base movements in different nations are thus strategically linked and affected by which areas of responsibility they fall under or adjoin, this section will be divided roughly following its scheme and some of its terminology.

Africa

Middle East

Europe

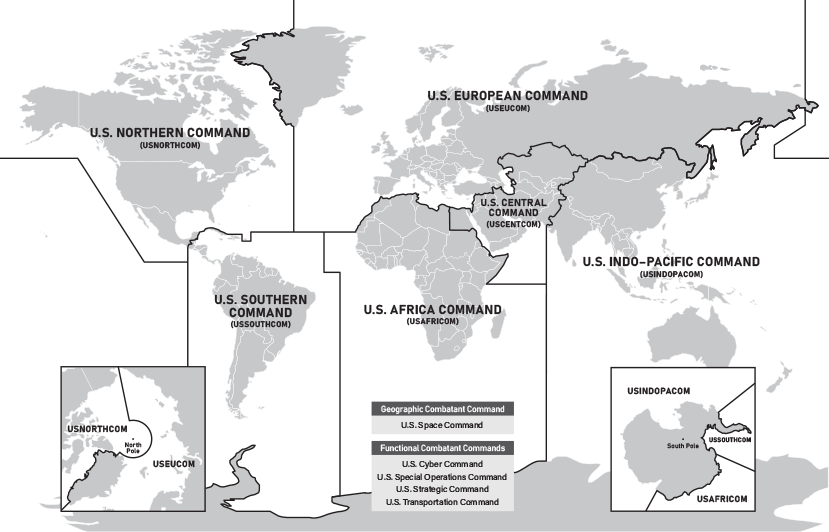

Indo-Pacific

The U.S. designates the area covering the Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean, and much of Asia as USINDOPACOM. It is the oldest and largest of the U.S.'s unified commands, and it has been referred to by the DOD as its "priority theater". The DOD has identified competition with China as the organizing principle of the Indo-Pacific posture since the early 2010s.[24] Its area of responsibility covers more area than any of the other geographic commands and shares borders with all five of the other geographic commands.[25]

U.S. military presence in the Indo-Pacific is headquartered in the occupied nation of Hawaiʻi,[26] whose sovereign government the US Navy overthrew in an 1893 coup.[27] Some of the US's most significant overseas bases and forces are in the Indo-Pacific, with many positioned in south Korea and Japan, as US strategy in this area targets China, DPRK, and Russia. This area is the location of the world's largest maritime exercise, the US-led RIMPAC.[28]

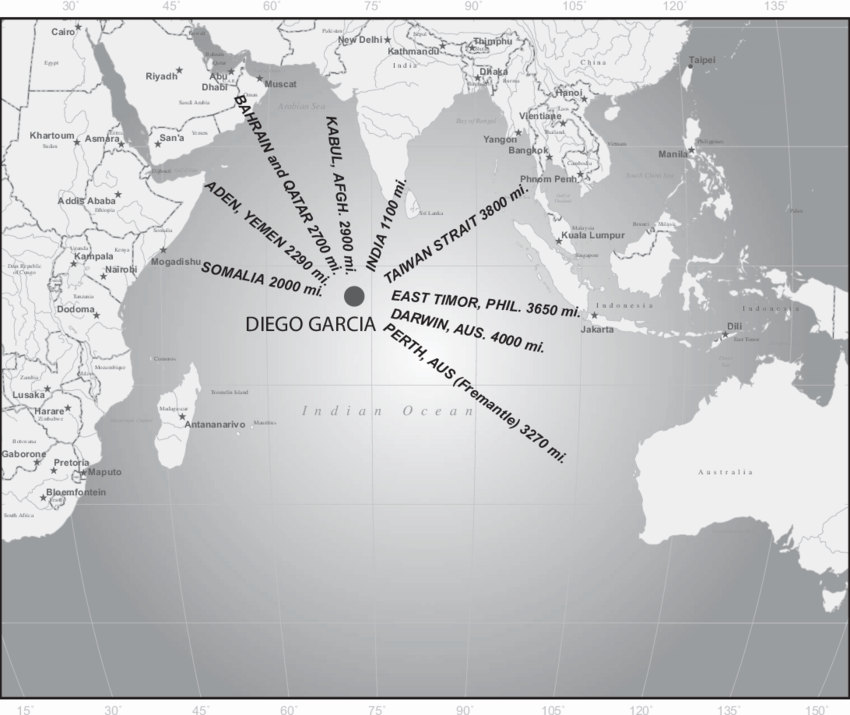

In Oceania, the U.S. has significant air and naval bases on its occupied colony Guam, and operates the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site at Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands. The Department of Defense is building a high-frequency radar system in Palau. Additionally, the U.S. military has ties with Fiji, Papua New Guinea, and Tonga.[26] Also significant is the Diego Garcia base in the Indian Ocean, built after the forced displacement of the island's inhabitants through a joint US-UK effort.[29][30]

Japan

In Japan, Okinawa has more than half of the 54,000 U.S. troops based in Japan.[24] Okinawa was once the independent Ryukyu Kingdom which was then colonized by Japan, later falling under the rule of the United States for 27 years (until 1972),[31] and is currently regarded as a Japanese prefecture.[32]

Korea

The single nation of Korea has been divided by U.S. occupation since shortly after the Second World War, when the U.S. refused to withdraw its forces and helped orchestrate the holding of separate elections in the south, establishing the "Republic of Korea," a U.S. puppet state ruled by a series of right-wing dictatorships, which the U.S. continues to occupy and reserves control over the south Korean military during wartime. This puppet state is postured against the DPRK, which formed after the U.S.-sponsored separate elections in the south.[33]

Anti-US and anti-base movements in south Korea have existed since the beginning of U.S. occupation in Korea and continue to this day, both on the mainland of the Korean peninsula and on Jeju Island, where locals and their supporters (including activists from other occupied nations in the Pacific)[34] attempted to prevent the construction of a naval base for over a decade.[35]

Hawaiʻi

Guam

Philippines

Diego Garcia

Diego Garcia is part of the Chagos Islands in the Indian Ocean, where a U.S. base is sustained on a British land lease. Over a ten year period beginning in 1965, a joint US-UK effort expelled the population in order to build a US military base.[29][30] John Pilger, writing in Al Jazeera, explained: "People were herded into the hold of a rusting ship, the women and children forced to sleep on a cargo of bird fertiliser. They were dumped in the Seychelles, where they were held in prison cells, and then shipped onto Mauritius, where they were taken to a derelict housing estate with no water or electricity. Twenty-six families died there in brutal poverty, nine individuals committed suicide, and girls were forced into prostitution to survive."[36]

The strategically significant location of Diego Garcia enables the U.S. military to reach numerous locations, for example helping to launch the U.S. bombings of Iraq and Afghanistan.[36][37]

Though not strictly an anti-base movement, there is a movement for the survivors of the forced expulsion to be able to return to their home. However, this has been blocked by various political maneuvers by the West, including by the establishment of a marine nature reserve in the area, which would prevent them from engaging in necessary subsistence fishing if they were able to return.[36][30]

North America

South America

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 “I use the term “antibase movement” because it is widely used by movement members and scholars and because such movements, strictly speaking, are “anti-” in the sense that they are opposed to some aspect of the life of a base or its personnel.”

David Vine (2019). No Bases? Assessing the Impact of Social Movements Challenging US Foreign Military Bases, vol. Volume 60, Number S19. [PDF] Current Anthropology. - ↑ Yeo, Andrew. "Not in Anyone's Backyard: The Emergence and Identity of a Transnational Anti-Base Network." International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 53, No. 3 (Sep., 2009), pp. 571-594. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ David Vine, Patterson Deppen and Leah Bolger. "Drawdown: Improving U.S. and Global Security Through Military Base Closures Abroad." Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, September 20, 2021. Archived 2024-03-12.

- ↑ Jawad, Ashar. "5 Countries With the Most Overseas Military Bases." Insider Monkey, December 15, 2023.

- ↑ "Why 90% Of Foreign Military Bases Are American." AJ+ on YouTube, Jan 13, 2022.

- ↑ “The Feminist Response to RIMPAC and the US War against China.” Friends of Socialist China, July 27, 2022. Archived 2023-09-22.

- ↑ Mohammed Hussein and Mohammed Haddad. "Infographic: US military presence around the world." Al Jazeera, 10 September 2021. Archived 2024-03-28.

- ↑ Chris Gelardi and Sophia Perez. “‘Biba Guåhan!’: How Guam’s Indigenous Activists Are Confronting Military Colonialism.” The Nation, October 21, 2019.

- ↑ Jedra, Christina. “How Hawaii Activists Helped Force the Military’s Hand on Red Hill.” Honolulu Civil Beat, March 14, 2022. Archived 2022-02-22.

- ↑ “American Nuclear Submarine Enters Jeju Naval Base.” Hankyoreh, 2017. Archived 2023-03-25.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Prashad, Vijay. “Why Does the United States Have a Military Base in Ghana?” Peoples Dispatch, June 15, 2022. Archived 2024-03-18.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 “Defending Our Sovereignty: US Military Bases in Africa and the Future of African Unity.” Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, July 5, 2021. Archived 2023-03-04.

- ↑ Mitchell, Jon. “NCIS Case Files Reveal Undisclosed U.S. Military Sex Crimes in Okinawa.” The Intercept. October 3, 2021. Archived 2022-08-06.

- ↑ "Bombing ends, but village still not free from past." Yonhap News Agency. September 12, 2012. Archived 2022-09-27.

- ↑ Shorrock, Tim. “Welcome to the Monkey House.” The New Republic. December 2, 2019. Archived 2022-09-26.

- ↑ "For People, Land, Air and Sea: Stop RIMPAC Military Exercises." Petition to Governor of Hawaii David Ige, started by World Can't Wait-Hawai`i. Change.org, May 17, 2018. Archived 2024-04-03.

- ↑ Yeo, Andrew. "Security, Sovereignty, and Justice in U.S. Overseas Military Presence." International Journal of Peace Studies, Volume 19, Number 2, Winter 2014. Archived 2023-04-13.

- ↑ "Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA): What Is It, and How Has It Been Utilized?" Congressional Research Service, March 15, 2012. (PDF). Archived 2024-04-15.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Agreement Between the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA and GHANA." May 9, 2018. United States Department of State.

- ↑ Maxwell Boamah Amofa. “The Sandhurst Colonial Mentality and the Rule of Law.” Modern Ghana. March 13, 2023. Archived 2023-02-14.

- ↑ Katie Bo Williams. “AFRICOM Adds Logistics Hub in West Africa, Hinting at an Enduring US Presence.” Defense One, February 20, 2019. Archived 2024-04-02.

- ↑ “USAFA Library Guides: Combatant Commands: Combatant Command Overview.” U.S. Air Force Academy.

- ↑ "Combatant Commands." U.S. Department of Defense. Archived 2023-04-15.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 "U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM)." Congressional Research Service, March 5, 2024.

- ↑ "USPACOM Area of Responsibility." U.S. Indo-Pacific Command.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "The Pacific Islands." Congressional Research Service, January 25, 2024. Archived 2024-02-11.

- ↑ Jon Olsen (2022-11-15). "Hawai’i—The Very First U.S. Regime Change." CovertAction Magazine. Archived from the original on 2022-11-16.

- ↑ Takahashi Kosuke. “US-Led RIMPAC, World’s Largest Maritime Exercise, Starts without China or Taiwan.” The Diplomat, July 01 2022. Archived 2024-02-26.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Asoka Bandarage. “U.S. Military Presence and Popular Resistance in Sri Lanka.” CovertAction Magazine, August 12, 2019. Archived 2023-10-03.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 David Vine. “The Truth about the U.S. Military Base at Diego Garcia.” Truthdig, June 15, 2015. Archived 2023-01-29.

- ↑ Sayo Saruta. “Okinawa’s Peace Movement Carves Its Own Path.” The Japan Times, March 4, 2024. Archived 2024-04-06.

- ↑ Moé Yonamine. “Fighting for Okinawa.” MR Online, July 28, 2017. Archived 2023-09-28.

- ↑ People's Democracy Party and Liberation School. “70 Years Too Long: The Struggle to End the Korean War.” 25 June 2020. Archived 2023-09-26.

- ↑ “With RIMPAC, South Korea Expands Its Military Footprint.” Friends of Socialist China, August 2022. Archived 2023-09-27.

- ↑ Benjamin, Medea. “Korea’s Jeju Island: A Model for Opposing Militarism.” Telesurenglish.net. teleSUR. 2015. Archived 2020-01-19.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Pilger, John. “How Britain Forcefully Depopulated a Whole Archipelago.” Al Jazeera, February 25, 2019. Archived 2023-03-31.

- ↑ Marsh, Jenni. “Is the United States about to Lose Control of Its Secretive Diego Garcia Military Base?” CNN, March 9, 2019.