More languages

More actions

| Barbados Ichi-rougan-aim | |

|---|---|

| |

| Capital and largest city | Bridgetown |

| Official languages | English |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

• President | Sandra Mason |

• Prime Minister | Mia Mottley |

| Area | |

• Total | 439 km² |

| Population | |

• 2019 estimate | 287,025 |

Barbados is an island country in the Caribbean.

History[edit | edit source]

Pre-colonization[edit | edit source]

Heywoods & Cojoba[edit | edit source]

The oldest human settlement on the island of Barbados is the site of Heywoods, which has been radiocarbon-dated to circa 2530–1750 BC. Archaeologists have uncovered human burials, food remains, and thousands of artifacts, including chipped shell adzes. Pottery, shell artifacts, and house remnants have been collected from these sites for years. [1]

These relics and structures were left behind by the Indigenous Arawak and Kalinago tribes, who migrated from the South American mainland through Trinidad and Tobago and eventually settled in Barbados. These peoples would move seasonally across the island to access different natural resources and to strengthen their social, economic, and political relationships with other tribes.[2]

Archaeological records reveal a culture that engaged in harvest festivals, ball games, and formal events for tribal diplomats, as well as more esoteric activities such as divination, ancestor veneration, fertility rituals, and the creation of Cemi, a spirit given physical form. Like other Caribbean cultures, their worldview was animistic, believing that everything in nature, plants, animals, stones, and water possessed a soul.[3]

Barbadians, like many other Caribbean peoples, participated in Cohoba ceremonies. In these rituals, shamans ground the beans of the cojobana tree into a fine snuff, which was then inhaled through a tube. The shamans guided participants through their spiritual journeys and interpreted their visions. It is believed that the cojobana tree is Anadenanthera peregrina and that its beans contain bufotenin, a derivative of DMT.[4]

The Indigenous Barbadians, who had lived on the island for thousands of years, had abandoned Barbados shortly before the English arrived. To avoid capture by Spanish slavers, they fled to neighboring islands such as St. Vincent and St. Lucia. The recent departure of the Barbadian peoples was evident to the early English colonists, who found abandoned villages, broken pottery, and tools made from conch shells scattered across the land.[5]

Colonization[edit | edit source]

Establishment & Indentured Servitude[edit | edit source]

On February 17th, 1627, the British colonist Captain John Powell and his men claimed the newly abandoned island of Barbados. His brother, Henry Powell, soon arrived with 80 colonists and 10 African slaves, establishing the first permanent British settlement near the area now known as Holetown. John Powell and his colonists enslaved 40 Arawaks from Guyana, on the South American mainland. These Arawaks were forced to clear forests, build shelters, and plant crops such as cassava, tobacco, and cotton. Due to overwork, exploitative conditions, and disease, most of the Arawaks died and were subsequently replaced with African slaves. [6]

Before the arrival of more enslaved Africans, the colonists had forcibly brought over Irish, Scottish, and Welsh indentured servants. Many of these Celtic servants were prisoners of war from the Wars of the Three Kingdoms and were shipped to Barbados to work on plantations. Upon arrival, they were sold as property to plantation owners. They were whipped, shackled, and subjected to severe punishments, any act of resistance often resulted in extended indentures or execution.[7]

Celtic women were not spared from abuse: rape, sexual assault and murder by British overseers were common and went unpunished. Although indentured servitude was not permanent like slavery, since it was limited to a set number of years and did not pass on to the servants’ children, the conditions and mistreatment were still brutal and had close resemblance to the abuse suffered by enslaved Africans.[8]

It is estimated that at least half of all Celtic indentured servants died before completing their contracts. In 1657, Richard Ligon wrote that these servants were treated with extreme cruelty and many died under the whip of forced labor. Letters from that era describe shiploads of newly arrived Celtic servants replacing those who had died. Those who survived the horrific conditions often never received their promised payment, remained poor and landless, and many eventually left Barbados after gaining their freedom, seeking better opportunities in Jamaica.[9]

Chattel Slavery & Sugar[edit | edit source]

175 of the richest British colonists in Barbados each owned, on average, 116 enslaved Africans who worked on their plantations. Collectively, these 175 colonists owned half of the arable land on the island. Within this land, enslaved Africans cultivated sugarcane, sweet potatoes, yams, and plantains, as well as African medicinal plants such as ricin and tamarind. The cultivation of these plants was both an act of resistance and a way of preserving their African heritage.[10]

Because the enslaved population was banned from entering taverns, rum shops, and other public establishments, they created their own fermented alcoholic drinks from sugarcane. These beverages were similar to African palm wine and grain beers traditionally made by their ancestors. In this way, the enslaved sought to preserve elements of their cultural heritage despite their oppression. Drinking in the sights of their masters was considered disrespectful and a challenge to authority, so the enslaved gathered in caves across Barbados to socialize and drink in secret. These caves served as temporary refuges from plantation life and allowed people from neighboring plantations to form social connections and maintain a sense of community.[11]

Every large plantation in Barbados had a designated area for enslaved housing, known as the “Negro Yards.” These areas initially consisted of simple wooden huts, but over time, they evolved into coral stone houses.[5]

During the Sugar Revolution, wealthy English investors poured money into Barbados. The settlers used this capital to build sugar mills and purchase vast numbers of enslaved Africans through the transatlantic slave trade. Many small farms were formed into large plantations, and between the 1600s and 1834, Barbados became Britain’s most profitable settler colony. The immense profits from sugar production helped fuel Britain’s expanding economy.[12]

The shift to sugar cultivation required a massive labor force. While the island already had some African slaves and Celtic indentured servants, demand for labor grew so high that the planters imported enslaved Africans in enormous numbers. By the 1660s, Africans had become the majority population on the island.[13]

Barbados was the first British colony to fully adopt a system of African chattel slavery, setting the model for other colonies in North America and the Caribbean. The Barbados Slave Code of 1661, officially titled “An Act for the Better Ordering and Governing of Negroes,” legally defined enslaved Africans as property rather than human beings. This law provided the colonists with legal justification for the dehumanizing abuse of Africans and became a template for slave codes in other British and American colonies.[14]

The law granted slaveholders the legal right to commit acts of violence, including torture, murder, rape, and severe whipping. Despite these brutal and repressive conditions, enslaved Africans developed new Creole languages, religious practices, and cultural traditions while preserving aspects of their ancestral heritage. Through these struggles and adaptations, they laid the foundation for what would become Bajan (Barbadian) identity.[15]

The Africans brought to Barbados came from various regions across West and Central Africa and spoke many different languages. Over time, as their connections deepened, they developed a shared Creole language as a form of resistance. This language evolved into Bajan Creole, which is still spoken in Barbados today.[16]

Like many other enslaved peoples, the Africans in Barbados used music as a means of building community and expressing resistance. Although drumming was banned by slaveholders, who viewed it as a threat to their authority, the enslaved improvised by using their bodies as instruments. This creativity later gave rise to musical genres such as calypso, spouge, and tuk.[17]

Although many enslaved Africans were Christianized by their masters, they retained aspects of their ancestral spiritual beliefs. The result was a fusion of African rituals and Christian faith. These early Bajan churches served not only religious purposes but also helped the enslaved rebuild fictitious family networks, as many had been torn from their real families. Within these communities, people referred to each other as “sister,” “brother,” “auntie,” and “uncle,” reinforcing a sense of belonging and familial love.[18]

They also practiced communal child care, inspired by traditional African customs, taking collective responsibility for the well-being of one another’s children. Their African culinary traditions survived as well, with dishes such as cou-cou, pudding and souse, and the indigenous pepper pot, which they adapted and updated with African ingredients and techniques.[19]

The first recorded slave rebellion in Barbados occurred in 1649. Although the uprising was planned in secrecy, it was betrayed by an enslaved man who revealed the details to his slaveholder. As a result, eighteen of the resistance leaders were executed. While this was the first overt rebellion, many other forms of resistance took place more subtly, through sabotage, escape, and the preservation of their culture. The 1649 rebellion gave the colonial authorities justification to formalize control through the Barbados Slave Code of 1661, though these oppressive laws were already being planned.[20]

The British colonizers themselves also faced tensions with the administration in Britain. Governors of the island were appointed by the Crown rather than by the settlers, leading to conflicts when these governors imposed taxes or made policy changes without consulting local elites.[21]

Over time, the settlers protested and petitioned for local governance, arguing that, as English subjects, they were entitled to the “rights and freedoms of Englishmen.” Their efforts succeeded with the creation of the House of Assembly in 1639, giving them limited self-rule.[21]

The 1700s marked the peak of Settler Barbados, the height of sugar production and profitability. The island was densely populated, with around 745 plantations producing sugar, molasses, and rum, and approximately 80,000 enslaved Africans laboring on them. Wealthy colonist families such as the Codringtons and Draxes dominated the island’s economy and society.[15]

By the mid-18th century, Barbados had become one of the most densely populated places in the world, due to the vast number of sugar plantations and the enormous enslaved population required to sustain them. This placed severe strain on the island’s natural resources. The ancient rainforests were cleared for agriculture, leaving only small strips that survive today thanks to modern conservation initiatives.[15]

Barbados’s proximity to West Africa made Bridgetown, its capital, a central hub of the transatlantic slave trade during the 1700s. A large slave market existed in what is now National Heroes Square in Bridgetown.[22]

The Cage, built in 1688 on Upper Broad Street in Bridgetown, served as a site of public punishment and humiliation. Equipped with a pillory and a whipping post, it was initially used to punish enslaved Africans for minor offenses but later became a place where captured runaways were detained, publicly whipped, and displayed. The Cage stood near the modern-day Chamberlain Place.[23]

As the 18th century drew to a close, Barbados faced a severe agricultural crisis. Nearly two centuries of deforestation and sugarcane monoculture had exhausted the soil, leading to nutrient depletion and declining crop yields. Colonists resorted to importing guano fertilizers, but this proved insufficient, especially as foreign competition increased.[24]

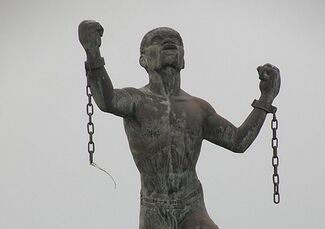

Bussa’s rebellion was the first major, though ultimately unsuccessful, uprising that helped set in motion the series of resistance leading to the abolition of slavery in the British West Indies. His death and the rebellion itself became the spark that ignited the abolitionist movement and inspired resistance across the entire British Empire.[25]

The rebellion had 400 core members, but it grew to as many as 5,000 enslaved people across the island to join the uprising. Approximately 1,000 rebels were killed when the colonial militia and the British West India Regiment violently suppressed the resistance. Afterward, 144 rebels were executed and 123 were exiled to other colonies. Bussa himself was killed during the fighting on his plantation, along with many of his closest allies.[25]

After the rebellion, the British colonial authorities tightened their control over the enslaved population. However, the political climate within the empire began to shift, as the uprising fueled growing support for the abolitionist cause. During this period, the colonialists brutally tortured and flogged enslaved people to extract confessions, all while maintaining eighty days of martial law.[25]

Although the British Empire abolished the transatlantic slave trade in 1807, slavery itself continued to exist in colonies such as Barbados, South Africa, and several smaller territories.[26]

Churches, reformers, and abolitionist groups continued to campaign tirelessly throughout the empire to bring an end to slavery. As the Barbadian economy began to decline, enslaved people increased their resistance, working slowly, sabotaging equipment, and escaping whenever possible. These small acts of resistance, combined with the abolitionist and religious push for reform, eventually forced colonial settlers to make small concessions, including changes in plantation management and demands for financial compensation from the British Crown in anticipation of emancipation.[27]

In 1833, the British Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act, which legally ended slavery throughout the empire. However, this was largely symbolic, as the law introduced an “apprenticeship system”, a so-called transitional period during which formerly enslaved people were required to continue working for their former masters for up to six years. Due to intense public criticism, this period was later reduced to four years.[28]

The apprenticeship system proved to be just as harsh and exploitative as slavery, prompting widespread condemnation from British abolitionists, newly freed Africans and the Church. Mounting pressure from these groups finally led to true emancipation in 1838, marking the end of slavery in Barbados and across the British Empire.[29]

Emancipation & Journey to Independence[edit | edit source]

After emancipation, life was far from easy for Barbadians. They continued to face systemic racism within the racial hierarchy that shaped both the economic and social structures of colonial society. Land remained concentrated in the hands of colonial families, leaving the majority of freed people landless, poor, and subjected to constant discrimination and food insecurity. The colonial elite maintained complete control over the government, as well as the legislative and judicial systems, ensuring the preservation of the racial order. [28]

The struggle for equality and self-determination would take over a century, culminating only with independence. In the years following emancipation, the lack of land ownership and persistent hunger forced many Barbadians to return to the plantations to earn penny wages under painful conditions. Over time, some managed to save enough money to become independent artisans, using the skills they had developed during slavery, such as carpentry, masonry, and construction, to earn a living.[28]

Gradually, freed Barbadians began pooling their resources to buy small plots of land, forming cooperative villages where they could live collectively and apply their agricultural knowledge. As these communities grew, they also established their own churches and schools, nurturing a new generation of Barbadian preachers and teachers.[5]

As land ownership spread, small-scale farms began appearing across the island, allowing more Barbadians to rely on subsistence farming rather than plantation labor. Increased access to education also led to social mobility, with more Barbadians seeking office jobs and higher education.[30]

By the late 19th century, a small but relatively wealthy class of educated Barbadians had emerged. This small group began to demand equality and representation, organizing through newspapers and labor and trade unions. As literacy spread among the formerly enslaved population, activism increased. Entering the 20th century, labor and trade unions became increasingly vocal, especially during and after the Great Depression (1929–1939), which caused deep economic hardship.[31]

In 1937, massive riots erupted across the British Caribbean, known as the 1937 Labor Rebellion. In Barbados, this movement gave rise to several trade unions that eventually evolved into political parties, including the Barbados Labour Party. In response to the unrest, the British Empire introduced light reforms, following recommendations from the Royal Commission. These reforms granted universal adult suffrage in 1951 and internal self-governance in 1961.[32]

Finally, under pressure from free Barbadians, trade unions, and non-colonial political parties, Barbados entered negotiations for independence with the United Kingdom. On November 30, 1966, Barbados became a sovereign and independent nation, though they still remain under a form of neo-colonialism. [33]

Independence[edit | edit source]

Neo-colonialism[edit | edit source]

Barbados became independent from the United Kingdom in 1966, but Queen Elizabeth remained the head of state until a republic was established in 2021.[34]

When Barbados won independence from Britain in 1966, despite the atrocities accompanying the settler colony and extraction of resources, Barbados received nothing but a 20 million bail-out to the slaveholders, which they finished paying in 2016. 11 years after Independence, the Barbadian representative, either the prime minister or the financial minister signed an IMF loan in 1977 which was the beginning of the neo-colonization of Barbados. Barbados became a member of the IMF just 5 years after Independence, on December 29st of 1970. [35]

The loan in 1977, was due to an export shortfall i.e the amount of profit from exports are lower than expected, due to it being the first loan from the IMF, it set no conditions for the loan unsurprisingly the future loans had structural conditions which the representatives accepted. The second IMF loan that Barbados took between 1982 - 1984 demanded complete economic reform from Barbados which they signed, the reason for signing was due to low sugar-cane exports, debt and a recession which harmed their tourism sector, the IMF demanded capitalist free market strategies like trade liberalization which damages domestic industries since they can’t compete against the global companies leading to massive unemployment and job losses. [36]

The removal of tariffs and restrictions on imports ensures that government revenue declines which harms the poorest as they are the ones most reliant on government revenue through social safety nets, the low living standards due to unemployment and destruction of domestic industry by the IMF meant many Bajans left the island for a better life, further deepening the economic crisis through brain-drain, which makes Barbados even more reliant on the IMF. [37]

In 2017, Barbados had 7 billion in debt to various international lenders like Inter-American Development Bank, Caribbean Development Bank and the IMF, in response to a debt that was 175% of the GDP of the country, the elected officials decided to sign another deal with the IMF in 2018 which demanded restructuring which entails, mass lay-offs of government workers, lower corporates taxes and the privatization of the public services. [38]

2 years later came the Pandemic which devastated the economy reliant on tourism as everybody had to be quarantined, the GDP shrank by 18% and unemployment lying around 10% in 2019 increased to 40% in early 2021. [39]

In June and December of 2020, the elected officials of Barbados signed multiple deals with the IMF, they added approximately 184 million of debt to them, which further deepen the debt and reliance on the IMF as well as empower the IMF when it pertains to Barbados governance.[40]

Barbados may be independent and a republic since 2021, the country is still forced to make decisions that are imposed by the western financial institutions and if they take any action to actually empower themselves with all the debt and reliance on these western institutions which can impose harsh controls on any of their actions. So Barbados may be independent and a republic in name, it is still in the same position of dependence and under control of a western entity, [41]

Barbados was only forced to take these loans in the first place, due the colonizers extracting all the wealth and resources from the land, this extraction and theft was ongoing for centuries leaving the Bajan people with unproductive soils and struggling to establish themselves, though whether Barbados had fertile land as well as lots of resources wouldn’t change the situation as the elected officials of Barbados are faithful followers of the neo-liberal path. [42]

Good news, is that in the February of 2019 Barbados signed onto and became a member of China’s Belt and Road Initiative and agreed to increased developmental ties to China which shows a sign of potential move towards the Global South and abandoning the predatory West and its financial institutions. [43]

In June of 2025, Barbados prime minister Mia Mottley met with Chinese officials to discuss potential BRI projects and admitted that Barbados recent economic recovery was only possible with funding from the Belt and Road Initiative and the Chinese officials assured her that they will strengthen their bilateral relationship. [44]

China is currently involved in multiple projects in the country as a result of the Belt and Road as China is funding the re-development of the National Stadium, Sam Lord’s Castle and the Scotland District Road as well as the construction of a food security centre and two major agricultural centers. Talks are also underway between China and Barbados to expand the capacity of the Queen Elizabeth Hospital by 40%. [44]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, Scott M (2016). Verification of an Archaic Age Occupation on Barbados, Southern Lesser Antilles..

- ↑ Drewett, Peter L (2014). Excavations at Heywoods, Barbados, and the Economic Basis of the Suazoid Period in the Lesser Antilles..

- ↑ José R. Oliver (2009). Caciques and Cemi Idols.

- ↑ Jaime R. Pagán-Jiménez (2017). Recent Archaeobotanical Findings of the Hallucinogenic Snuff Cojoba.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Maaike S. de Waal (2019). PRE-COLONIAL AND POST-CONTACT ARCHAEOLOGY IN BARBADOS.

- ↑ Jacqueline Luqman (2021-12-09). "Britain’s Legacy of Brutal Slavery in Barbados" Hood Communist. Archived from the original on 2021-12-09. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ↑ Jerome S. Handler, Matthew C. Reilly (2017). Enslaved Africans and European Indentured Servants in Seventeenth-Century Barbados.

- ↑ John Gilbert McCurdy (2020). The Cambridge World History of Violence: 'Part III - Intimate and Gendered Violence - 13 - Gender and Violence in Early America'. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Richard Ligon (1657). A True & Exact History of Barbados. Humphrey Mosley.

- ↑ Edward B. Rugemer (2022). The Rise of the Planter Class. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ↑ Maaike de Waal, Niall Finneran, Matthew Reilly, Douglas V. Armstrong (2019). Pre-Colonial and Post-Contact Archaeology in Barbados. Past, present and future research directions..

- ↑ Justin Roberts (2024). Fragile Empire - Slavery in the Early English Tropics, 1645–1720. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Borthwick Institute for Archives (2024). Slavery in the West Indies. [PDF] University of York.

- ↑ Justine Collins (2021). Common Law, Civil Law, and Colonial Law: '12 - English Societal Laws as the Origins of the Comprehensive Slave Laws of the British West Indies'. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Barbados National Commission for UNESCO (02/12/2014). The Industrial Heritage of Barbados: The Story of Sugar and Rum. UNESCO World Heritage Convention.

- ↑ Ericka A. Albaugh, Kathryn M. de Luna, Maureen Warner-Lewis (2018). Tracing Language Movement in Africa: '15 - The African Diaspora and Language: Movement, Borrowing, and Return'. Oxford University Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190657543.001.0001 [HUB]

- ↑ Stephen Rowley (2011). Bajan Mummers: Have they lost the plot?. [PDF]

- ↑ Jerome S. Handler (2000). SLAVE MEDICINE AND OBEAH IN BARBADOS, CIRCA 1650 TO 1834. [PDF] Brill on behalf of the KITLV, Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies. doi: 10.1163/13822373-90002570 [HUB]

- ↑ Diana Paton (2021). The driveress and the nurse: Childcare, working children and other work under Caribbean slavery.. Past & Present: A Journal of Historical Studies. doi: 10.1093/pastj/gtaa033 [HUB]

- ↑ Hilary Beckles (1984). Black Rebellion in Barbados: The Struggle Against Slavery, 1627-1838. Antilles Publications. 9789768004024 ISBN 9768004029, 9789768004024

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 LARRY GRAGG (2003). 'Englishmen Transplanted': The English Colonization of Barbados 1627-1660: 'Chapter Three. Establishing a Colony, 1625–1660'. Oxford Academic. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199253890.003.0003 [HUB]

- ↑ Pedro L. V. Welch (2003). Slave Society in the City: Bridgetown, Barbados, 1680-1834. I. Randle, J. Currey, Kingston. 9780974215556 ISBN 0974215554, 9780974215556

- ↑ Barbados Museum and Historical Society. "Plan for Public Cage" the Slavery and Remembrance project by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- ↑ Moore, Jason W. (2003). Theory and Society, vol. 32: '"The Modern World-System" as Environmental History? Ecology and the Rise of Capitalism'. Springer Nature.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Trevor Rome (2009). The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest: 'Bussa (d. 1816) and the Barbados Slave Insurrection'. doi: 10.1002/9781405198073.wbierp0276 [HUB]

- ↑ National Archives (UK). Slavery: 'How did the Abolition Acts of 1807 and 1833 affect the slave trade?'. [PDF]

- ↑ Keith Grint (2024). A Cartography of Resistance: Leadership, Management, and Command: 'Resisting Slavery in the British West Indies'. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198921783 doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198921752.001.0001 [HUB]

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 William A. Green (1991). British Slave Emancipation: The Sugar Colonies and the Great Experiment 1830-1865: 'Free Labour and the Plantation Economy and Free Society: Progress and Pitfalls'. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191675515 doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198202783.001.0001 [HUB]

- ↑ Joseph Sturge, Thomas Harvey (2011). The West Indies in 1837. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511783913 doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511783913 [HUB]

- ↑ Nurse, James O.J. (1970). Small Scale Farming in Barbados. The Caribbean Agro-Economic Society (CAAES) > 5th West Indies Agricultural Economics Conference, April 5-11, 1970, Roseau, Dominica. doi: 10.22004/ag.econ.264109 [HUB]

- ↑ Proctor, Robert (1980). Early Developments In Barbadian Education. Journal of Negro Education. doi: 10.2307/2294967 [HUB]

- ↑ Curtis Jacobs (2007). The Barbados Workers' Union and the Politics of Barbados, 1961-1986. Barbados Workers' Union Headquarters, Bridgetown: Symposium of Frank Walcott "Celebrating a Trade Union Legend".

- ↑ Rafael Cox-Alomar (2007). An Anglo‐Barbadian dialogue: the negotiations leading to Barbados' independence, 1965–66. The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs and Policy Studies. doi: 10.1080/0035853042000300160 [HUB]

- ↑ Lewis Eliot (2021-12-16). "It’s all in the flag: Bussa’s Rebellion and the 200-year fight to end British rule in Barbados" The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2022-06-16. Retrieved 2022-09-04.

- ↑ Patrick Blagrave. "Barbados: At a Glance" International Monetary Fund.

- ↑ UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN (2001). An Analysis of Economie and Social Development in Barbados. [PDF]

- ↑ Przemyslaw Kowalski (2005). Impact of Changes in Tariffs on Developing Countries' Government Revenue. OECD Trade Policy Papers. doi: 10.1787/210755276421 [HUB]

- ↑ Randa Elnagar. "IMF Executive Board Approves US$290 million Extended Arrangement Under the Extended Fund Facility for Barbados" International Monetary Fund.

- ↑ Anton Dobronogov (2021). Barbados: COVID-19 Response and Recovery Development Policy Financing. [PDF] The World Bank.

- ↑ Marlon Madden. "IMF to finance extra $180 million" Barbados Today.

- ↑ Finch, Natasha (2024). Barbados: Out of the Shadow of its Colonial Past?. [PDF] Houghton St Press - LSE JOURNAL of GEOGRAPHY & ENVIRONMENT.

- ↑ Noel Chase (2019). Barbados’ Debt Crisis: The Effects of Colonialism and Neoliberalism. [PDF] Latin American, Caribbean, and U.S. Latino Studies Honors Program 4.

- ↑ CIJN Staff Writers. "The Caribbean Engages the Belt and Road Initiative" Caribbean Investigative Journalism Network.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "PM Mottley Holds Talks With Chinese And EU Ambassadors". Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade.