More languages

More actions

| Brunei Darussalam Negara Brunei Darussalam | |

|---|---|

| |

| Capital and largest city | Bandar Seri Begawan |

| Official languages | Malay |

| Demonym(s) | Bruneian |

| Government | Unitary Islamic absolute monarchy |

• Sultan and Prime Minister | Hassanal Bolkiah |

| Area | |

• Total | 5,765 km² |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 460,345 |

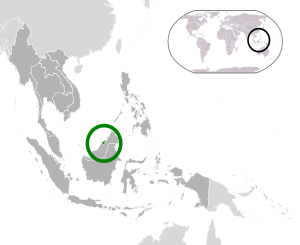

Brunei, officially Brunei Darussalam, is an absolute monarchy in Southeast Asia which shares the island of Borneo with Malaysia and Indonesia, with the former splitting the country into two. Brunei is a member of ASEAN and the Commonwealth of Nations.

History[edit | edit source]

Precolonization[edit | edit source]

Pre-Sultanate Era[edit | edit source]

The single oldest known instance of archaeological evidence of human activity within Brunei is the Kota Batu archaeological site, where they found the remains of a thriving trade port city and settlement dating to the 6th to 7th centuries CE, with artifacts like Chinese coins and porcelain from the Tang, Song, and Yuan dynasties. Kota Batu is Malay for “Stone Fort.” Despite the majority of the settlement being made of wood and bamboo, there were some stone remnants remaining. Remnants of the local cultures are diverse, including ancient timber and stone houses, old covered walkways, and the man-made island of Pulau Terindak.[1]

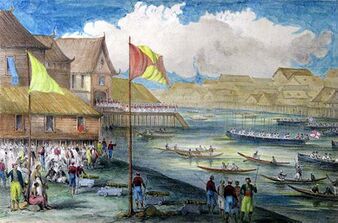

The site was continually occupied over centuries. Chinese records from 977 CE, specifically the Chu-fan-chi trade record, named Brunei “Pu-ni” and mentioned it was protected by timber walls, while European records from 1521 CE mention a city built on water with a stone-walled palace. In the 15th and 16th centuries, the area now had royal mausoleums, specifically the tombs of two sultans: Sultan Sharif Ali and Sultan Bolkiah.[2]

Limau Manis was a secondary port, or feeder, to Kota Batu in the pre-sultanate era. There are thousands of Chinese porcelain shards from both the Song and Yuan dynasties at the archaeological site, and carbon-dating places them around the 10th century to the mid-14th century CE. Limau Manis was a bustling, large riverine trading port. There were also local earthenware, iron slags, and beads.[3]

Over 50,000 ceramic shards from China during the Song and Yuan dynasties have been collected from the site, with fewer from the Ming and Qing periods, as well as from Thailand (Thai Sukhothai wares) and Vietnam (Annam wares). Due to the narrow Sungai Limau Manis river channel, there is a prevailing theory that large ships at that time anchored in the Brunei Bay area, and smaller local ships transported goods from there to the Limau Manis port.[4]

Brunei was a vassal state under the Srivijaya Empire, an Indonesian maritime empire that was the center and spreader of Buddhism in the region. Srivijaya was based on the island of Sumatra. It did not have direct control over Brunei and mainly expected it to pay tribute as a tributary state, as Srivijaya controlled the Strait of Malacca and the Strait of Sunda. Chinese records at this time call “Po-Ni” (Brunei) a wealthy kingdom with a fleet of warships to protect its trade. Despite the proximity to the Srivijaya Empire, Buddhism did not spread much in Brunei at that time.[5]

Due to Srivijaya being the center of Buddhism, specifically Mahayana Buddhism, and due to the vassalage of Brunei, this spread to Brunei on a small scale, blending with local traditions in small pockets. Srivijaya began facing constant conflicts, including a major invasion in 1025 CE by the Chola dynasty under Raja Raja Chola I, who captured the Srivijaya king, Sangrama Vijayottunggavarman.[6]

Srivijaya lost its influence over Brunei around the 13th century, due to the Chola invasion and shifting trade routes, which sealed the already fragile state of the empire. Brunei’s sovereignty lasted only for a short period, as in the 14th century it became a vassal of the Majapahit Empire according to the Nagarakretagama, a 14th-century Javanese text.[7]

In 1363 CE, Brunei’s ruler Awang Alak Betatar changed his name to Muhammad Shah and converted to Islam while establishing himself as the first sultan of Brunei and subsequently the Sultanate. Reasons for the conversion may have included contact with Muslim traders and his marriage to a Johor princess.[8]

Sultanate Period[edit | edit source]

Brunei’s Sovereignty[edit | edit source]

According to archaeological and Portuguese historical accounts, the Sultanate was fully institutionalized later, around the 15th–16th century. However, during the early 14th century, the Sulu Kingdom rebelled and launched major attacks on Kota Batu, the capital of Brunei at that time, looting its treasury, gold, and sacred pearls. Brunei was left weakened by the assault from the Sulu Kingdom and had to be rescued by a Majapahit fleet, which repelled the Sulu forces. In the initial stages of the establishment of the Sultanate of Brunei, a Chinese report from this period describes Brunei as poor and totally controlled by Majapahit.[9]

Brunei’s independence from the Majapahit was a gradual process in the late 14th century, driven primarily by the decline of Majapahit and the intervention of Ming Dynasty China. Throughout the late 14th century, the Majapahit Empire began to wane. After the powerful prime minister Gajah Mada died in 1364 and King Hayam Wuruk died in 1389, the empire entered a period of internal conflict, with a major civil war known as the Regreg War severely draining the empire’s financial resources and weakening its ability to enforce control.[10]

Sultan Muhammad Shah, understanding the weakening of the Majapahit Empire, began to seek alternative protection, namely from the Ming Dynasty. The largest move toward this goal occurred when Sultan Abdul Majid traveled to Nanjing, China, with a large delegation in 1408 to formalize a tributary relationship and seek the Emperor’s recognition. Sultan Abdul Majid died in China around October 1408 and was buried there. The Yongle Emperor respected the dying wishes of the sultan and sent a powerful mission to the Majapahit Empire, ordering them to stop demanding tribute from Brunei.[9]

As Ming China was more powerful than the weakened Majapahit, the latter accepted the demands of the Yongle Emperor. With Majapahit threatened, Brunei was now able to operate freely as a sovereign state around the year 1408.[11]

Golden Age[edit | edit source]

Due to Brunei’s location, it became a profitable and safe port along the maritime Silk Road, attracting merchants from China, the Malay Archipelago, and India. Brunei controlled valuable resources such as camphor, spices, pearls, and gold. The reign of the fourth sultan, Sharif Ali, was the period during which the Islamic nature of the sultanate was spread and firmly solidified through the building of the first mosque in Brunei and the creation of the royal emblem (the Panji-Panji).[11]

Sharif Ali constructed the stone ramparts of Kota Batu, reportedly hiring Chinese builders to assist in the construction, according to the Silsilah Raja-Raja Brunei. This may indicate a potential link between the Ming Dynasty and Brunei. Under Sharif Ali, legal developments were established, such as the Hukum Kanun Brunei, which integrated Islamic law into the national legal framework. He spent much of his reign participating in the maritime Silk Road trade network and deepening Islamic influence within the country, including adding Darussalam to the country’s name.[9]

Sultan Bolkiah ascended the throne, and the reign of Sultan Bolkiah is seen as the peak of Brunei’s golden age. During his rule, he expanded the territory of the sultanate and was known as Nakhoda Ragam (“The Singing Admiral”) due to his naval conquests. He extended Brunei’s control over the coast of Borneo (Sarawak and Sabah, now under Malaysia), as well as Manila and the Sulu Archipelago, both of which are under the Philippines today.[9]

Tomé Pires was a Portuguese apothecary and colonial diplomat, and in his work Suma Oriental he wrote about Bruneian merchant ships being a vital part of maritime trade within the Southeast Asian archipelago. These trade networks extended from the southern Philippines to major trade centers in the region, including the port of Guangzhou in China. According to Pires, Bruneian merchants utilized junk (zong/zhong) ships in their long-distance trade; junk ships are a type of Chinese vessel with a flat bottom.[12]

Imperial Decline[edit | edit source]

Death of Bolkiah[edit | edit source]

Following the death of Sultan Bolkiah and the abdication of his son, the empire experienced a decline from its imperial peak. His son, Sultan Abdul Kahar known as Raja Siripada and Marhum Keramat began his six-year reign between 1524 and 1530, and his short rule marked the continuation of the golden age of the Bruneian Sultanate.[9]

During his brief period of rule in Brunei, he expanded the already large territories of the sultanate through naval expeditions. The sultanate’s strength during this period is best exemplified by the arrival of the Portuguese, who sought to trade and establish influence. A Portuguese diplomat, Gonçalo Pereira, visited in 1530 but failed in his efforts, as Brunei was sufficiently self-sufficient. Sultan Abdul Kahar also developed a new form of coinage known as pitis, replacing the previously used Chinese coins.[9]

Sultan Abdul Kahar developed a form of cult of personality within Brunei, as he was highly regarded by the people for his character and qualities. He was described as a religious man possessing berkeramat (supernatural abilities), which is why he came to be called Marhum Keramat (“The Saint”) after his death. For unknown reasons, he abdicated the throne around 1530 in favor of his nephew, Saiful Rijal. After his abdication, he took the title of Paduka Seri Begawan Sultan Abdul Kahar and served as co-regent alongside his nephew, Sultan Saiful Rijal.[9]

Following his abdication, he remained an influential figure, serving as co-regent or co-ruler alongside his nephew. He played a crucial advisory role, which is best exemplified during the Castilian War, when the Spanish invaded the Bruneian capital. The Bruneian leadership was forced to flee to Jerudong, where they planned and executed their counteroffensive.[9]

In which they succeeded.

Castilian War[edit | edit source]

The Castilian War, which began in 1578 and ended the same year, was a notable conflict fought between the Spanish Empire and the Sultanate of Brunei. It began as a Spanish justification using religious and territorial disputes in the Philippines, which Brunei considered to be part of its territory.[9]

In essence, it began with the Spanish colonial governor of the Philippines demanding that Brunei cease any Islamic influence within the Philippines, with the goal of spreading Christianity through Spanish missionaries. Because Imperial Spain claimed Manila as their colonial capital, they directly intruded on Brunei’s territory, which included Bruneian satellite states. The conflict was further complicated when the brother of the Sultan of Brunei, betrayed the sultan by defecting to the Spanish and offering Brunei to them in exchange for being allowed to seize the throne from his brother.[9]

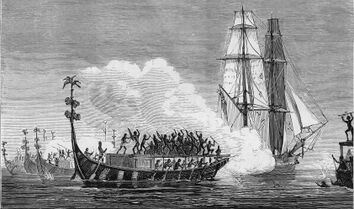

It started in March of 1578, when Francisco de Sande, the colonial governor, led an expedition from Manila consisting of 40 galleons, 400 colonizers, and 1,500 Filipinos. They eventually besieged the Bruneian capital at the time, Kota Batu. Due to the betrayal and the sudden attack, the Bruneians were outgunned by Spanish artillery. Sultan Saiful Rijal and his uncle, Paduka Seri Begawan Sultan Abdul Kahar, fled to Jerudong and began planning their counteroffensive.[9]

Jerudong served as their temporary headquarters. The primary architect of the counteroffensive was the Sultan’s brother, Pengiran Bendahara Sakam, who is said to have rallied approximately 1,000 Bruneian soldiers. The Bruneian warriors leveraged their local knowledge of the geography to attack Spanish positions, including poisoning the Spanish water supplies in the capital. Despite being outnumbered and outgunned, they effectively utilized guerrilla warfare.[9]

The Bruneian forces used hit-and-run tactics to keep the Spanish confined to the capital while poisoning their supplies and water, and preventing them from accessing the inland resources on which they relied. As a result of the poisoning and restricted access to food and supplies, the Spanish experienced a catastrophic outbreak of cholera and dysentery, which decimated their colonial forces.[9]

On June 26, 1578, after only 72 days of occupying the capital, the Spanish fled back to Manila. Before retreating, they burned the grand fifth-tier mosque and looted 170 Bruneian artillery pieces.[9]

While Western sources typically describe the disease as a spontaneous and random outbreak that forced the Spanish to flee, historically it was a combination of Bruneian poisoning of the Spanish and the sustained pressure from Bruneian resistance that ensured Brunei’s victory.[9]

Victory & End of Expansion[edit | edit source]

Following the Spanish retreat from the capital, another Spanish fleet appeared off Brunei’s shores in 1579, however, unlike the previous year, this fleet departed without any hostilities or attempts at intervention. Around this time, Sultan Babullah of Ternate, a sultanate in present-day Indonesia, made diplomatic decisions to deepen ties between the two sultanates as an anti-colonial alliance against invading European powers.[9]

Despite the Spanish not engaging in any hostilities with Brunei at this time, they were still surveying and charting nearby regions such as Pulangi in the Philippines. The Castilian War ended Brunei’s imperial influence; while the Spanish failed to conquer Brunei, they nonetheless prevented it from regaining its foothold in Luzon (Philippines). As a result, Brunei gradually became more of a city-state rather than an expansionist empire within Indochina.[9]

Brunei was revived beginning with Muhammad Hasan, the ninth sultan of Brunei. Under his rule, Brunei re-acquired many lost territories, such as Sulu (now a province of the Philippines) and Sambas (a province of Indonesia). His reign saw the construction of two square-shaped palaces at Kota Batu, with a fortified city surrounding the palaces and equipped with artillery. He also commissioned the construction of a bridge linking Tanjong Kindana - Chendana to the island of Pulau Chermin.[9]

By the late 1590s, the Spanish sent a formal letter to Brunei requesting the normalization of relations and the resumption of trade, effectively ending two decades of subtle hostility. This also allowed the Spanish to focus on the Spanish–Moro Wars in the Philippines without having to look over their shoulder.[9]

In 1600–1601, the Dutch admiral Olivier van Noort, a colonial imperial agent of the Dutch Republic, visited Brunei and laid the foundation for Dutch, Portuguese, and British involvement in the region, which gradually eroded Brunei’s economic dominance in Indochina. To compound this damage, the Spanish had severed important trade routes through their occupation of Manila. As Brunei was gradually weakened economically by the presence of these European imperial powers, what ultimately sealed its fate was the Bruneian Civil War.[4]

Bruneian Civil War[edit | edit source]

By 1660, the Bruneian Sultanate, along with the presence of European imperial powers in the region, had ensured that the Bruneian economy was in decline, largely due to the division of authority between the sultan and the Bruneian nobility. This division of power encouraged growing factionalism within the ruling class, with nobles such as the Bendahara (Chief Minister) acquiring increasing authority. The fragile balance of power between the sultan and the nobles beneath him ultimately shattered in 1661.[9]

This occurred during the reign of Sultan Muhammad Ali. In 1661, a cockfight was held between two aristocrats: Pengiran Muda Bongsu, the Sultan’s son, and Pengiran Muda Alam, the Bendahara’s son. During the cockfight, the Sultan’s son’s rooster lost, and the Chief Minister’s son mocked him, which, for unknown reasons, led the Sultan’s son to murder the Chief Minister’s son and then flee.[13]

The Chief Minister, Abdul Hakkul Mubin, demanded that the prince be executed according to customary law, but Sultan Muhammad Ali refused to surrender his son. This refusal triggered a political crisis and angered Abdul Hakkul Mubin and his followers. On November 16, 1661, the Chief Minister and his supporters stormed the palace and killed everyone inside. Sultan Muhammad Ali was then strangled to death by Abdul Hakkul Mubin while the sultan was praying Asr in the palace mosque.[13]

Following the murder, the Chief Minister proclaimed himself Sultan Abdul Hakkul Mubin and became the 14th Sultan of Brunei, but he faced opposition from supporters of the murdered sultan. To pacify the angry populace, the new sultan appointed Pengiran Muhyiddin, the late sultan’s grandson, as the new Chief Minister. While Muhyiddin remained publicly loyal, he was secretly plotting with a small group of followers to overthrow Sultan Abdul Hakkul Mubin.[9]

Muhyiddin’s followers destabilized the capital at night through harassment, creating fear and disorder. This was intended to convince the sultan to move the capital from Bandar Seri Begawan to Pulau Chermin, at the mouth of the Brunei River. After Sultan Abdul Hakkul Mubin left Bandar Seri Begawan, Muhyiddin seized the capital and established himself as Sultan Muhyiddin, becoming the 15th Sultan of Brunei.[13]

The sultanate was now divided between two rival sultans, each fighting for authority. Sultan Abdul, unable to retake the capital from Sultan Muhyiddin, retreated west to Kinarut (modern-day Sabah), where he constructed a fortress and ruled from there. From this stronghold, Sultan Abdul waged a guerrilla war alongside the Bajau and Dusun peoples against Sultan Muhyiddin. The favorable geography of Sabah allowed Sultan Abdul’s forces to easily repel Muhyiddin’s naval assaults.[9]

Due to this prolonged war, trade was devastated, river settlements were depopulated, and the nobility became fractured, as both sides suffered from dwindling manpower and resources. After numerous failed naval assaults, Muhyiddin launched a final attack against Abdul, which was repelled. Abdul took advantage of this outcome, abandoned Kinarut, and returned to Pulau Chermin to prepare for a final defense. Determined to end the stalemate, Muhyiddin requested military and logistical assistance from the Sultanate of Sulu, offering eastern Sabah in return.[14]

With the assistance of the Sultanate of Sulu, Muhyiddin’s forces bombarded Pulau Chermin from Tanjung Kindana. Pulau Chermin was completely devastated, and Sultan Abdul was captured and executed at the Great Mosque on Pulau Chermin in 1673, bringing the civil war, which had lasted 12 long years, to an end.[13]

This civil war, along with the earlier Castilian War, drained Brunei’s resources, encouraging Sultan Muhyiddin to focus on consolidating the sultanate rather than expanding it. Both conflicts severely weakened Brunei. Muhyiddin’s transfer of Sabah to the Sultanate of Sulu became the historical root of the modern dispute, with the Philippines viewing itself as the successor to the Sulu Sultanate and Malaysia inheriting the claim through the North Borneo Chartered Company as a lease.[9]

Colonization[edit | edit source]

European Encirclement[edit | edit source]

Throughout the 1700s, European companies and pirates began to spring up across the coastlines of Borneo, primarily due to the weakened state of Brunei. Specifically, the British began exploring Borneo to occupy trade routes and exploit these maritime networks. The British had a commercial interest in enabling and funding piracy within Borneo, as it was common for them to offer ships to local raiders in exchange for raiding vessels carrying pepper and other resources.[15]

It was common for the British in Borneo to label local maritime activities by Indigenous Borneans as piracy in order to justify their colonial expansion. The British East India Company established an Admiralty court in India to try these “pirates” in Kolkata rather than having to bring them to London. The British East India Company was a state-backed imperial and colonizing weapon; it gathered information on Brunei’s ports, rulers, conflicts, and resources.[16]

Britain was funding piracy within the territory of Brunei while simultaneously framing itself as an anti-piracy entity, when in reality these justifications formed the foundation for delegitimizing Brunei’s sovereignty, justifying future British naval attacks, and portraying itself as civilizing the hordes. Britain and the East India Company strengthened relations and trade with local chiefs within Brunei in order to fragment the country.[16]

As the local traders and chiefs dealt directly with the European traders and companies the Sultanates revenue base shrank and lost their authority over Sarawak and Sabah as it became more symbolic. It was intentional erosion of the authority of Brunei utilizing their various state-backed companies that acted more as weapons, though Britain was primarily focused on occupying Brunei it was rather ensuring they controlled the sea-lanes to China while countering the Dutch and Spanish influence within the region. [9]

The White Rajah[edit | edit source]

The White Rajah, or James Brooke, was an English colonizer who was originally working for the East India Company and later turned pirate. Brooke was given £30,000 by his father, who worked as an East India Company judge, with that £30,000 being worth around £4.7 to £4.8 million today when accounting for inflation.[9]

James Brooke used this inherited wealth to purchase The Royalist, a private yacht. Using this yacht, he explored Southeast Asia while actively trying to determine which rulers were weakened and which regions were unstable. All the while, he employed the narrative that he was there to civilize and act as an anti-piracy presence, particularly noting that Brunei had been weakened by the British East India Company and various European companies.[17]

By the time James Brooke reached Sarawak, which was under Brunei, an ongoing rebellion by the local Maya and Dayak people was taking place. In order to curry favor with the Bruneian governor, he struck a deal with him to suppress the rebellion. He sent his forces to attack the rebel strongholds, used naval guns to destroy their fortifications, and aimed to kill key leaders and collapse the organized resistance.[17]

Over time, he took advantage of the Sarawak people’s distrust of the Bruneian governor and accused Pengiran Indera Mahkota, the governor, of corruption and abuse, positioning himself to rule in his place. Brooke carefully reframed the narrative as himself restoring order, portraying himself as a sort of white savior. He began to rule as the “White Rajah” after levying these accusations.[17]

James Brooke and his forces actively took part in “anti-piracy” raids, during which they captured and killed supposed pirates while, in reality, intentionally misidentifying locals as pirates to justify killing, stealing, and capturing them. Naturally, in these raids, he was often supported alongside official British warships, which has led many to question whether James Brooke was truly a private individual or rather a proxy tool for the British Empire.[17]

Annexation[edit | edit source]

After the loss of Sarawak to the supposed private individual James Brooke, around 1846 the British attacked and occupied Bandar Seri Begawan.[9]

Britain set its sights on occupying Labuan, a Bruneian island that was geographically strategic. The British Empire, with the help of James Brooke, who portrayed Brunei as incapable of controlling piracy and chaos within the region, lobbied to annex Labuan. The British Empire accused Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien II of harboring pirates, failing to control coastal raiders, and being hostile to British interests.[18]

These accusations were used as justification for the invasion of Bandar Seri Begawan. In July 1846, British warships bombarded Bandar Seri Begawan, destroying large sections of the capital and intentionally targeting government structures. The bombardment killed vast numbers of the local population, and immediately after the attack the Sultan was forced to accept the Treaty of Labuan, which entailed giving the British Empire Labuan and its surrounding islands.[9]

A year later, they forced the Sultan to sign another treaty that gave the British Empire expanded trading rights and banned Brunei from ceding any part of the country to other imperial states. In essence, this locked Brunei into complete economic dependence on the British Empire. Brunei lost control over Brunei Bay and its customs revenue and now had a British naval presence at its doorstep.[9]

As the British took possession of Labuan Island, James Brooke was appointed as its first governor. The White Rajahs continued to annex land such as the Baram and Trusan districts, and in 1877 the Sultan was forced to lease or cede land in the east to the British North Borneo Chartered Company. In 1890, Sarawak under James Brooke annexed the Limbang District, splitting the sultanate into two.[19]

Due to the British gradually occupying and colonizing the entirety of Brunei, Sultan Hashim Jalilul Alam Aqamaddin was forced to sign the 1888 Treaty of Protection, which made Brunei a British Protectorate. Britain controlled its foreign and domestic policies, in other words, Brunei became a colony with a limited degree of autonomy.[20]

British Protectorate[edit | edit source]

Brunei became a British protectorate in 1888, which it remained until it achieved independence in 1984. It was placed under various different structures of British governance throughout this period. During the British protectorate, it retained its monarchy, but everything was governed by the British, making it a form of puppet or ceremonial monarchy.[9]

By the late nineteenth century, Brunei was continually being forced to give up land to Britain, the British North Borneo Company, and the Brooke dynasty. Fearing that Britain and its proxies would fully annex Brunei, Sultan Hashim Jalilul Alam Aqamaddin signed the 1888 Treaty of Protection. British protectorate policy preserved the Sultan to prevent discontent among the population while still ensuring imperial control over Brunei’s strategic resources and maintaining an imperial presence in Southeast Asia.[9]

The treaty failed to prevent annexation completely, as in 1890 Charles Brooke of the Brooke dynasty annexed Limbang. Britain allowed this to happen, as the Brooke dynasty functioned as its proxy. As Britain continued to permit the Brooke dynasty of Sarawak to annex territory from Brunei, Malcolm McArthur wrote a report in which he understood that Britain intended to fully annex Brunei. He conducted an investigation into Brunei and advised that, rather than annexation, Britain should place a British administrator in power.[21]

This system was called the Resident System, where the British Resident completely governed the country, the resident fully governed on all matters except for Malay customs and Islam within Brunei, unsurprisingly the investigator Malcom Mcarthur became the first Resident. Within bourgeois circles there is a tendency to claim that this system of colonization wasn’t colonization rather a ‘’protective system’’ despite overwhelming evidence of the British actively allowing annexation despite under the supposed protectorate but also the British themselves creating the root cause for needing protection, piracy, the Brooke Dynasty, the British North Borneo Company and the British East India Company.[21]

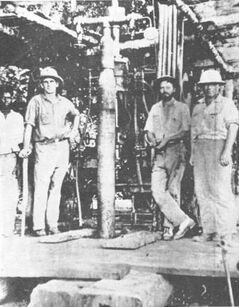

Oil Discovery[edit | edit source]

In 1929, oil was discovered in the town of Seria, Brunei. This discovery of commercially exploitable oil transformed Brunei’s economy and its importance to the British. Oil revenue concentrated wealth in the palace of the Sultan and the coffers of the British, linking Brunei to the global web of capitalist and imperialist circles. This oil production rebirthed Brunei as a rentier state and intensified existing deep social inequality: the wealthy ruling comprador class became anchored to imperial markets, while the working class of Brunei remained characterized primarily by agriculture and forestry.[9]

The tool the British used for the exploitation of Bruneian oil was the British Malayan Petroleum Company, in 1922 the British Malayan Petroleum Company (BMPC) purchased oil-prospecting rights that gave them a monopoly over mining and exploration. Exploitation only reached large-scale production with six million barrels annually by 1940, the Sultanate only received a royalty of two shillings per ton which is 10% of the profits, with 90% of profits going to British stakeholders and the British Borneo Petroleum Syndicate.[22]

The British utilized military force to secure the uninterrupted exploitation of oil in Brunei. Consequently, a permanent military presence was established, including the Royal Gurkha Rifles; they remain stationed in the town of Seria to this day.[22]

Japanese Occupation[edit | edit source]

On December 16, 1941, ten thousand soldiers from the Japanese Kawaguchi Detachment landed at Kuala Belait. They marched toward the capital, Bandar Seri Begawan, which fell by December 22. With insufficient defensive forces, the British and Europeans prioritized destroying the oil fields and retreating over confronting the Japanese troops.[9]

Under Japanese occupation, Brunei was merged into a single entity known as the Miri-Shu (Miri Prefecture), with its capital in Sarawak. Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin remained a ceremonial figurehead for the Japanese, much as he had been under the British protectorate. To stave off local discontent, he was awarded a pension and Japanese honors. Additionally, the Japanese maintained stability by retaining local Malay administrators rather than replacing them with Japanese officials.[9]

Although the Japanese did not replace local officials, they initiated a form of cultural subjugation similar to that of the British. Their policy, known as Nipponisation, sought to remove English influence by banning the English language in schools and replacing it with Nihongo. Additionally, workers and students were required to sing the Japanese national anthem every morning and bow towards the Imperial Palace in Tokyo[9]

The Imperial Japanese forces committed widespread atrocities, including torture, starvation, massacres, and enslavement. Many locals were enslaved during this period, which devastated communities. Japan’s primary goal was to extract resources from Southeast Asia, as the nation lacked sufficient domestic supplies, particularly in preparation for World War II. All of these actions were driven by the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere ideology, which sought to establish a grand Japanese Empire encompassing all of Southeast Asia and Northeast China.[23]

Independence[edit | edit source]

The Japanese occupation shattered the myth of British invincibility, fueling local anti-colonial ambitions. This surge in nationalism accelerated the movement toward independence and decolonization. These nationalist and leftist currents placed significant strain on both Britain and the monarchy. Consequently, the intense political pressure led to a major concession: the signing of the 1959 Constitution.

This agreement ended the British Resident system, allowing Brunei to assume full control over its internal administration. In the early 1960s, the British and Malayan governments proposed incorporating the Bruneian Sultanate into a new nation-state called Malaysia. Although the Sultan was initially interested, he withdrew at the last minute. His decision was driven by concerns regarding his seniority among the Malay rulers, the requirement to share Brunei's oil wealth, and strong opposition from the local population.[24]

In 1962, an armed insurrection led by the North Kalimantan National Army (TNKU) aimed to overthrow the monarchy and resist unification into Malaysia. The TNKU also demanded immediate independence. Fearing for his status, the Sultan requested British military assistance in typical comprador fashion. British troops flew in from Singapore and crushed the resistance. This revolt made the Sultan paranoid, leading him to delay the independence process by two decades. Consequently, the Sultan suspended the constitution and ruled by emergency decree[25]

In the late 1970s, the Sultan and Britain signed the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation, agreeing that Brunei would assume full responsibility for its own defense and foreign affairs after a five-year transition period. On January 1, 1984, Brunei achieved its status as an independent, sovereign nation.[9]

Today, Brunei finds itself in a complex situation: it functions as a neocolony with a comprador state that benefits from deep connections to its imperialist and colonial overlord, primarily through the Shell Company and the maintenance of a rentier state structure.

LGBT Discrimination[edit | edit source]

Brunei has some of the worst conditions for LGBT people in world with Equaldex ranking them the second worst country behind Afghanistan. In 2019 the punishment for homosexual acts was changed from ten years imprisonment to the death penalty for married men, 100 lashes for unmarried men, and ten years imprisonment for women.[26] Despite these human rights violations, Brunei still continues to receive support from imperialist powers who themselves claim to support LGBT rights.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Trails to Tropical Treasures – A Tour of ASEAN Cultural Heritage (1998).

- ↑ Antonio Pigafetta (1521). Brunei and Spain 1521 – Borneo History.

- ↑ Gabriel Y. V. Yong & Noor Hasharina Hassan (2022). Historical Geography of the Limau Manis Archaeological Site. [PDF]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Asiyah Az-Zahra Ahmad Kumpoh, Stephen C. Druce, Nani Suryani Abu Bakar (2022). Brunei Historiography.

- ↑ Pierre-Yves Manguin. The Oxford Handbook of Early Southeast Asia: 'Srivijaya'.

- ↑ Fhadrul Irwan. Srivijaya : a Buddhist centre in maritime Southeast Asia (7th-11th Centuries).

- ↑ Suhadi, Machi. Masalah Negara Vasal Majapahit.

- ↑ Robert Nicholl (2011). Some Problems of Brunei Chronology.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 9.15 9.16 9.17 9.18 9.19 9.20 9.21 9.22 9.23 9.24 9.25 9.26 9.27 9.28 9.29 9.30 9.31 9.32 9.33 9.34 Graham Saunders, A History of Brunei. (1994). [PDF] Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Theodoor Gautier Thomas Pigeaud (1960). Java in the 14th Century: A Study in Cultural History.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Wang Gungwu (1959). The Nanhai Trade: A Study of the Early History of Chinese Trade in the South China Sea. [PDF]

- ↑ Tomé Pires (1512). Suma Oriental: The Spice Trade of the East.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Teh Gallop, Annabel (1997). Sultan Abdul Mubin of Brunei: Two literary depictions of his reign. [PDF]

- ↑ de Vienne, Marie‑Sybille (2015). Brunei: From the Age of Commerce to the 21st Century.

- ↑ JOHANNES WILLI of GAIS. Early relations between the English and Borneo. [PDF]

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 C Nathan Kwan. ‘Discredit upon the British name and rule’: British Suppression of Piracy and the History of International Law in the South China Sea. [PDF]

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Steven Runciman. The White Rajahs: A History of Sarawak from 1841 to 1946.

- ↑ Rabiqah N. H. B. M. Yusof. Building and Enshrining an Absolute Monarchy. [PDF]

- ↑ Agathe Le Vaslot. Development Actors and Indigenous.

- ↑ Asiyah Az-Zahra Ahmad Kumpoh, Nani Suryani Abu Bakar. [https://fass.ubd.edu.bn/staff/docs/AK/Asiyah%20Nani%202021%20The%20Bruneian%20Concept%20of%20Nationhood.pdf The Bruneian Concept of Nationhood the 19th and 20th Centuries: Expressions of State Sovereignty and National Identity]. [PDF]

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 McArthur, M. S. H (1904). Report on Brunei. FO 572/39, British Foreign Office.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Harper, G. C (1975). The Discovery and Development of the Seria Oilfield.

- ↑ Beasley, William G. (1991). Japanese imperialism 1894-1945.

- ↑ The Constitution of Brunei Darussalam (1959).

- ↑ Alexander Nicholas Shaw (2016). British counterinsurgency in Brunei and Sarawak, 1962–1963: developing best practices in the shadow of Malaya.

- ↑ "LGBT Rights in Brunei" (2024). Equaldex.