More languages

More actions

Christianity | |

|---|---|

| Type | Monotheistic, Abrahamic |

| Scripture | The Bible |

| Origin | ~150 CE |

| Number of followers | 2.6 billion |

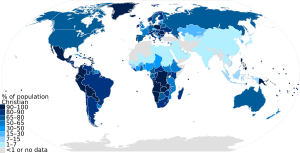

Christianity is an Abrahamic and monotheistic religion as well as the largest religion on Earth with about 2.6 billion adherents as of 2020.[1] Over 45,000 sects of Christianity exist, of which the Roman Catholic church is the largest in terms of membership, followed by Protestantism (which itself is extremely fragmented) and Eastern Orthodoxy.[2]

Christianity, along with most religions in general, has been used by the ruling class during various stages of economic and historical development, mostly as a tool of justifying the social and economic order relative to that historical epoch, which would further secure the power and wealth of said ruling class. Things such as a "divine mandate" or a "god-given mission" and things of that nature have been used, be it in past or present eras, to legitimize slavery,[3][4] feudalism,[5] fascism,[6] genocide,[7] capitalism,[8] and colonialism.[9] While modern times have seen a number of progressive currents within the Christian church, such as Liberation theology and other movements of progressive clerics and laypeople, the largest and most organized Christian churches continue to advance reactionary, anti-communist causes.[10]

With the rise of literacy, scientific developments, among other factors, adherence of religion has declined, with an increasing rate of secularism, agnosticism, atheism, and other lack of religion.[11]

History[edit | edit source]

Early development[edit | edit source]

The early history of Christianity is unclear, with there being few historically-attested facts and many myths. Christianity's own history says that it began during the life of Jesus,[note 1] though the earliest historical account of his life was made at around 70 CE—decades after his legendary death—it is unclear how and when Christianity first appeared as a distinct religion.[12]

Divergence from Judaism[edit | edit source]

By the middle of the first century CE, a particular group of Jews had emerged that had begun to adopt heterodox views compared to normal followers of Judaism. This nascent Jewish sect is known by modern scholars as "Jewish-Christians", or "Jewish followers of Jesus". The Jewish-Christians had applied the theological view of a "savior" or "messiah" to Jesus.[13] Jesus's followers soon split into two groups: a revolutionary nationalist group that sought to overthrow Roman Rule and a more conservative faction that sought spiritual and not material redemption. Roman authorities largely destroyed the revolutionary group their suppression of the First Jewish Revolt between 66 and 73, but the conservative group survived until the leadership of Paul of Tarsus. They recorded a revisionist and depoliticized narrative of Jesus's life that became the New Testament of the Bible.[14]

While the first followers of Jesus were located almost entirely in Roman Judea (modern-day Palestine), by means of missionaries, this early form of Christianity was able to spread across the Roman empire. These first theological missions were originally targeting the Jewish communities outside Judea, but over time, gentiles (non-Jews) became early Christians as well. As decades passed, the theological difference between Jewish-Christians and Jews got to a point where those Jewish-Christians became Christians, particularly after more non-Jews became members of this sect.[13]

Early Christianity[edit | edit source]

By the year 150 CE, early Christianity had appeared as a separate religion from Judaism. Furthermore, these early Christians lived in often urban communities, located in the heart of the Roman empire. The early Christians would begin to form a common clerical structure and theological doctrine. This phase in Christianity is known today as the ante-nicene period, that is, the time before the first council of Nicaea, which happened in 325 CE.[13]

The time from 150–325 CE saw a wide range of Christian sects appear, often failing to concur with each other on things such as the divinity of Christ, the nature of the trinity, and other things such as that. The ante-nicene period also saw a large amount of persecution, namely from Roman authorities, with the Romans executing many early Christians.[14] but as the turmoil of the crisis of the third century along with the hardships of the fourth and fifth centuries wore on, and as the old economic order of slavery and patricians was slowly replaced by the emerging economic system of feudalism, the citizens and denizens of the moribund Roman empire slowly left behind their ancient paganistic religion and embraced Christianity.[13]

By the fourth century CE, Christianity had become relatively common in Roman civilization, and in 313 CE, Constantine put the Edict of Milan in effect, legalizing the practice of Christianity. His successor, Theodosius, banned paganism and gave temple estates to the church.[14]

Late classical age[edit | edit source]

In the year 380 CE, Christianity was made the official state religion of the Roman empire. Furthermore, with Christianity now enjoying acceptance at a governmental-level, the structure of the clergy would now change greatly. Among some of the most politically impactful changes would include the formation of a system known as the pentarchy, a system where five bishops would be appointed to manage the theological workings of five locations, or sees. These five locations included Rome, Constantinople, Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria. These bishoprics largely survive to this day, for example, the present bishop of rome is also known as the pope - and head of the Vatican City State of the Roman Catholic Church.

By the end of the western part of the Roman empire in 476 CE, Christianity had firmly rooted itself in both the government and peoples of Europe and North Africa. During the fifth century CE, the theological leaders of Christianity were forced to adapt to the rapidly changing political and social climate of that time. The Christian clergy had to contend with the theological ideas of the new barbarian overlords, while still maintaining loyalty with the clergy of the remaining part of the Roman Empire.[13]

Medieval period[edit | edit source]

Spread of Christianity during the low medieval period[edit | edit source]

In spite of the rapidly decaying societal state of western Europe in the decades following the fall of the western Roman empire, Christianity was nonetheless able to spread rapidly by means of missionaries. The primary regions that were converted to Christianity were the British Isles, largely Anglo-Saxons at first, and the barbarian rulers located in what is now France. Later on, the pagan regions in what is now northern Germany were forcefully converted to Christianity.

However, the area where Christianity was the dominant religion, would contract in size during the rise of Islam, which happened during the seventh and eighth centuries CE. Before the Islamic invasions, regions such as northern Africa and the Levant (a region comprising modern-day Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria) were largely Christian, and ruled by Byzantium, a Christian empire; after the Islamic invasions of around 622 to 750 CE, these region would become mostly Muslim, and remain that way into the present era.[15]

Eastern Roman Christianity during the low medieval period[edit | edit source]

Unlike in western Europe, eastern Europe, mainly the Eastern Roman Empire, saw much more political stability. As such, mutations in the theological or clerical structures were generally slower than with the Christian church's western counterpart.

East-West Schism[edit | edit source]

Due to centuries of political and geographic separation between the Christianity of western Europe and the Christianity of eastern Europe, there soon began to appear differences between the two churches. Many of these discrepancies while relatively small, such as the way in which ritualistic bread was prepared, others were relatively big, such as the practice of clerical celibacy, or the structure of the clergy.

These theological conflicts reached a metaphorical boiling point when, after a set of heated theological debates, the western and eastern Christian churches both excommunicated each other in 1054. By this point, the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches had become distinct from each other.

Crusades[edit | edit source]

In 1095, Pope Urban began the First Crusade at the Council of Clermont. A feudal army of thousands of knights entered Syria in 1097, taking Antioch in 1098 and Jerusalem in 1099 and then forming four crusader states. The crusaders looted and destroyed cities and mass murdered civilians. A small military elite took control of the region and severely exploited the Arab peasantry while maintaining a hostile relations with neighboring states.

In the decades following the First Crusade, Islamic states centralized and struck back against the crusaders, with the Second Crusade of 1146–48 failing to stop Muslim resistance. Saladin united Egypt and Syria in 1183 and destroyed the entire crusader army of Jerusalem in 1187 at the Battle of Hattin.[16]

In the Fourth Crusade, the pope looted Constantinople (the capital of another Christian empire). He gave 25% of the loot to Venice, which had funded the crusader mercenaries.[17]

Renaissance and Reformation[edit | edit source]

By the time of the Renaissance, the Catholic Church was highly corrupt, with aristocratic Italian families fighting over the papacy and indulgences (forgiveness for sins) sold like commodities. Like the monarchy and nobility, the clergy owned massive plots of land and were very rich. In the 14th century, John Wycliffe translated the Bible into English for the first time, and possession of his translation instead of the traditional Latin version was punishable by death.[18]

In 1515, Pope Leo lifted the church's ban on charging interest on loans.[17]

Protestant Reformation[edit | edit source]

In 1517, the German cleric Martin Luther posted his a series of 95 theses criticizing the Catholic Church on the door of the Wittenburg Cathedral. He rejected the sale of indulgences and favored personal religious beliefs over the authority of priests. The Holy Roman Emperor threatened to execute him at the Diet of Worms in 1521, but he refused to rescind his beliefs and became the founder of Protestantism, which eventually spread to two-thirds of Germany. John Calvin led the second phase of the Reformation by creating a theocracy in Geneva and replacing the hierarchy of bishops with congregations of bourgeois elders. Protestantism largely ceased to be a popular force as many German princes hostile to the Pope and Holy Roman Emperor adopted it and targeted more radical Protestants like Thomas Müntzer. Much of southern Germany returned to Catholicism, but utopian socialist radicals led by Jan van Leyden took control of Münster until 1535, when conservative elites defeated them and murdered their leaders.[18]

Counter-Reformation[edit | edit source]

The Council of Trent met between 1545 and 1563 to reduce corruption in the church and reassert Catholic dogma. They banned church officials from holding multiple posts or buying and selling their posts. Pope Paul Farnese gave approval to the Jesuits, who participated in the colonization of America and subverted Protestant-ruled states in Europe. In 1542, the Pope reestablished the Inquisition to repress non-Catholics across Europe.[18]

Beliefs[edit | edit source]

Christian doctrine is based on the Bible, a collection of Scripture that consists of the Jewish Bible (which Christians call the "Old Testament") and the New Testament (which is exclusively Christian). There are a number of different Christian religious groups with competing beliefs, but the one unifying factor in all of them is belief in Jesus Christ. Most Christian churches believe that Jesus was, in some form or another, God.[10]

Demographics[edit | edit source]

The overwhelming majority of Latin Americans are Christian, including over 90% in Bolivia, Ecuador, Paraguay, and Peru. The only Latin American country without a Christian majority is Uruguay, with a 44% Christian population. Many Latin American countries are transitioning from Catholicism to Protestantism.[9]

External links[edit | edit source]

See also[edit | edit source]

Notes[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Aramaic: ישוע Koine Greek: Ἰησοῦς Latin: Iesus

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ "World Population" (2020). countrymeters.info.

- ↑ Donavyn Coffey (2021-2-27). "Why does Christianity have so many denominations?" Live Science.

- ↑ Edward J. Cashin (2001). Beloved Bethesda : A History of George Whitefield's Home for Boys. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865547223

- ↑ Juan Siliezar (2019-1-7). "Slavery alongside Christianity" Harvard Gazette. Retrieved 2022-6-16.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff (2007). Christian Values and Noble Ideas of Rank and their Consequences on Symbolic Acts.

- ↑ Roger Eatwell (2003). Reflections on Fascism and Religion.

- ↑ Willliam E. Weeks (1996). Building the Continental Empire: American Expansion from the Revolution to the Civil War (p. 61).

- ↑ Kate Bowler (2013). Blessed: A History of the American Prosperity Gospel. ISBN 9780199827695

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Religious Fundamentalism and Imperialism in Latin America: Action and Resistance" (2022-12-19). Tricontinental. Archived from the original on 2022-12-22. Retrieved 2023-01-05.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 M. P. Mcheldov (1978). Great Soviet Encyclopedia (3rd ed.), vol. 28: 'Christianity' (Russian: Boljšaja sovjetskaja enciklopjedija). [PDF] Moscow.

- ↑ Ronald F. Inglehart (September/October 2020). "Giving Up on God: The Global Decline of Religion" Foreign Affairs.

- ↑ Karen Armstrong (1993). A History of God: '3' (p. 79). Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780345384560

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Ivor J. Davidson (2004). The Birth of the Church: From Jesus to Constantine, A.D. 30-312. Baker Books. ISBN 9780801012709

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Neil Faulkner (2013). A Marxist History of the World: From Neanderthals to Neoliberals: 'The End of Antiquity' (pp. 55–56). [PDF] Pluto Press. ISBN 9781849648639 [LG]

- ↑ Fred M. Donner (2014). The Early Islamic Conquests. [PDF] Princeton University Press. ISBN 1400847877

- ↑ Neil Faulkner (2013). A Marxist History of the World: From Neanderthals to Neoliberals: 'European Feudalism' (pp. 80–82). [PDF] Pluto Press. ISBN 9781849648639 [LG]

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Ben Norton, Michael Hudson (2023-05-05). "Origins of debt: Michael Hudson reveals how financial oligarchies in Greece & Rome shaped our world" Geopolitical Economy Report. Archived from the original on 2023-05-28.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Neil Faulkner (2013). A Marxist History of the World: From Neanderthals to Neoliberals: 'The First Wave of Bourgeois Revolutions' (pp. 93–96). [PDF] Pluto Press. ISBN 9781849648639 [LG]