More languages

More actions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

<dpl style="width:100%;"> | <dpl style="width:100%;"> | ||

namespace=Library | namespace=Library | ||

notcategory=Reading lists|Songs|Video Transcripts | notcategory=Reading lists|Songs|Video Transcripts|Library works by Enver Hoxha | ||

includesubpages=false | includesubpages=false | ||

include={Library work} | include={Library work} | ||

Revision as of 15:53, 13 September 2024

A 'Double Standard' in Reporting News From Portugal | |

|---|---|

| Author | Michael Parenti |

| Publisher | The New York Times |

| First published | 1976-01-24 |

| Type | Article |

| Source | https://www.nytimes.com/1976/01/24/archives/a-double-standard-in-reporting-news-from-portugal.html |

23 November

- We don't have anything yet on this day, maybe soon! Why not read a random page?

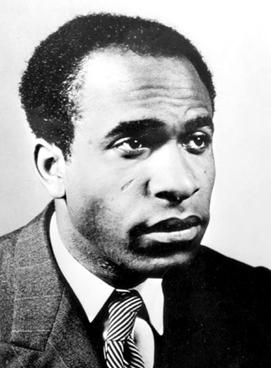

Frantz Fanon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 20, 1925 Fort-de-France, Martinique, French West Indies |

| Died | December 6, 1961 (aged 36) Bethesda, Maryland, USA |

| Cause of death | Leukemia |

| Known for | Black Skin, White Masks, The Wretched of the Earth |

Frantz Fanon (July 20, 1925 – December 6, 1961) was a psychiatrist, anti-colonial political theorist, author, and revolutionary from the Caribbean island of Martinique. He is the author of various works including Black Skin, White Masks (1952) and The Wretched of the Earth (1961).

Born as a colonial French subject, he eventually travelled to France for his education in psychiatry.

In the latter portion of his life, he was involved with the Algerian National Liberation Front (French: Front de Libération Nationale; FLN) in the Algerian independence struggle against the French.[1] He also worked in Tunisia with Algerian independence forces, and served as the Ambassador to Ghana for the Provisional Algerian Government. He passed away in 1961, after being diagnosed with leukemia.[2]

Fanon's political thought deals heavily with the implications and consequences of colonization, focusing considerably on anti-colonial struggles of his time as well as on the effects of colonization on the human psyche.

In 1953, Fanon was named the Head of the Psychiatry Department of the Blida-Joinville Hospital in Algeria. There, via his patients, Fanon gained increased insight into the torture and brutality ongoing under French rule. In 1956, Fanon resigned from his position to struggle for Algerian independence.[2][3] He documented French atrocities for the French and Algerian media.[4] According to Fanon, the only way for anti-colonial governments to prevent military coups is to politically educate the army and create civilian militias.[5]

Last 7 days (Top 10) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lemmy etc

- ↑ “Remembering Algerian Revolutionary Frantz Fanon.” teleSUR, Dec. 6, 2017. Archived 2022-08-18.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 “Martinique and Algeria’s Franz Fanon Remembered.” teleSUR. 2016. Archived 2023-03-19.

- ↑ John Drabinski. "Frantz Fanon." Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford.edu. Mar 14, 2019. Archived 2023-03-19.

- ↑ Vijay Prashad (2008). The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World: 'Algiers' (p. 121). [PDF] The New Press. ISBN 9781595583420 [LG]

- ↑ Vijay Prashad (2008). The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World: 'La Paz' (p. 139). [PDF] The New Press. ISBN 9781595583420 [LG]