More languages

More actions

| Some parts of this article were copied from external sources and may contain errors or lack of appropriate formatting. You can help improve this article by editing it and cleaning it up. (February 2023) |

BRICS | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa | |||||||||||||||||||

Official Logo | |||||||||||||||||||

The BRICS leaders in 2019, from left to right: Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin, Jair Bolsonaro, Narendra Modi and Cyril Ramaphosa | |||||||||||||||||||

Current members Member states and key leaders:

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Abbreviation | BRICS | ||||||||||||||||||

| Named after | Member states' initials | ||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | BRIC | ||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Intergovernmental organization | ||||||||||||||||||

| Purpose | Political | ||||||||||||||||||

| Headquarters | BRICS Tower | ||||||||||||||||||

| Fields | International politics | ||||||||||||||||||

| Funding | Member states | ||||||||||||||||||

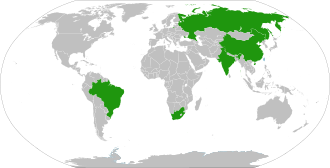

BRICS is an international platform for cooperation among emerging markets and developing countries: its members include Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Iran and Ethiopia.[1][2] The first four were initially grouped as "BRIC" (or "the BRICs") in 2001 by Goldman Sachs economist Jim O'Neill, who coined the term to describe fast-growing economies that would collectively dominate the global economy by 2050;[3] South Africa was added in 2010.[4] Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates were added as members in 2024. [5]

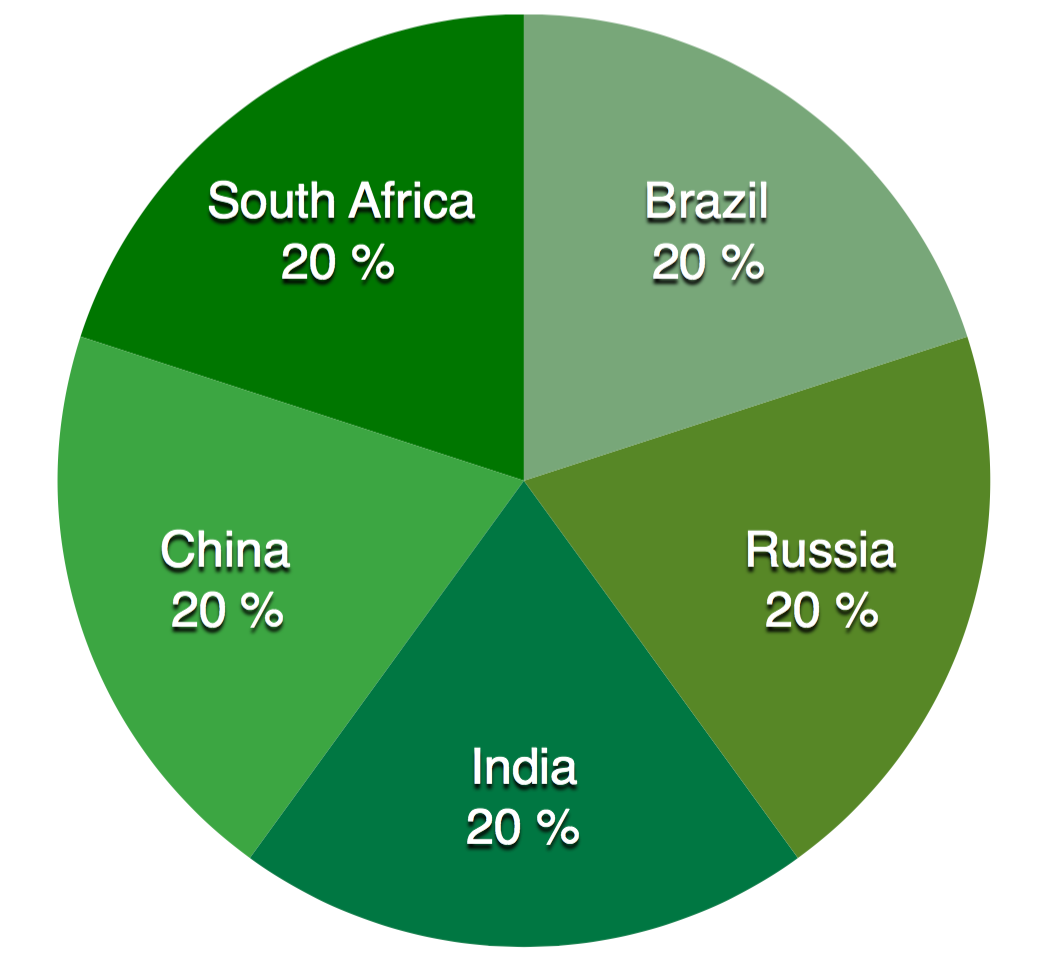

The BRICS have a combined area of 39,746,220 km2 (15,346,100 sq mi) and an estimated total population of about 3.21 billion,[6] or about 26.7% of the world's land surface and 41.5% of the global population. Brazil, Russia, India, and China are among the world's ten largest countries by population, area, and GDP, and are widely considered to be current or emerging superpowers. All five states are members of the G20, with a combined nominal GDP of US$26.6 trillion (about 26.2% of the gross world product), a total GDP (PPP) of around US$51.99 trillion (32.1% of global GDP PPP), and an estimated US$4.46 trillion in combined foreign reserves (as of 2018).[7][8]

The BRICS were originally identified for the purpose of highlighting investment opportunities, and had not been a formal intergovernmental organization.[9] Since 2009, they have increasingly formed into a more cohesive geopolitical bloc, with their governments meeting annually at formal summits and coordinating multilateral policies;[10] Russia hosted the most recent 16th BRICS summit between October 22-24, 2024. Bilateral relations among the BRICS are conducted mainly on the basis of noninterference, equality, and mutual benefit.[11]

The BRICS are considered the foremost rival to the G7 bloc of leading advanced economies,[12] announcing competing initiatives such as the New Development Bank, Contingent Reserve Arrangement, BRICS payment system, and BRICS basket reserve currency. Since 2022, the group has sought to expand membership, with several developing countries expressing interest in joining.[13] The BRICS have received praise from numerous commentators.[14]

History[edit | edit source]

Name[edit | edit source]

The term BRIC was originally developed in the context of foreign investment strategies. It was introduced in the 2001 publication, Building Better Global Economic BRICs by then-chairman of Goldman Sachs Asset Management, Jim O'Neill;[15] the term was coined by Roopa Purushothaman, who was a Research Assistant in the original report.[16]

For investing purposes, the list of emerging economies sometimes included South Korea, which expanded the acronym to BRICS or BRICK.

First BRIC summit[edit | edit source]

The foreign ministers of the initial four BRIC General states (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) met in New York City in September 2006 at the margins of the General Debate of the UN Assembly, beginning a series of high-level meetings.[17]A full-scale diplomatic meeting was held in Yekaterinburg, Russia, on 16 June 2009.[18]

The BRIC grouping's 1st formal summit, also held in Yekaterinburg, commenced on 16 June 2009,[19] with Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Dmitry Medvedev, Manmohan Singh, and Hu Jintao, the respective leaders of Brazil, Russia, India, and China, all attending.[20] The summit's focus was on improving the global economic situation and reforming financial institutions, and discussed how the four countries could better co-operate in the future.[21][20] There was further discussion of ways that developing countries, such as 3/4 of the BRIC members, could become more involved in global affairs.[20]

In the aftermath of the Yekaterinburg summit, the BRIC nations announced the need for a new global reserve currency, which would have to be "diverse, stable and predictable."[22] Although the statement that was released did not directly criticize the perceived "dominance" of the US dollar – something that Russia had criticized in the past – it did spark a fall in the value of the dollar against other major currencies.[23]

Entry of South Africa[edit | edit source]

In 2010, South Africa began efforts to join the BRIC grouping, and the process for its formal admission began in August of that year.[24] South Africa officially became a member nation on 24 December 2010, after being formally invited by China to join[25] and subsequently accepted by other BRIC countries.[24] The group was renamed BRICS – with the "S" standing for South Africa – to reflect the group's expanded membership.[26] In April 2011, the President of South Africa, Jacob Zuma, attended the 2011 BRICS summit in Sanya, China, as a full member.[27][28][29]

Potential further expansion[edit | edit source]

Since South Africa joined the BRIC grouping (now BRICS) in 2010, numerous other countries have expressed interest in joining the bloc, including Argentina and Iran. Both signaled their intent to join BRICS during meetings with senior Chinese officials, the current BRICS chair, over the course of the summer of 2022. Beijing backed Argentina's potential accession[30] following a meeting[31] between Argentine Foreign Minister Santiago Cafiero and Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi on the margins of the G20 Summit in Indonesia. China once again reiterated their support for Argentina’s potential application during a subsequent meeting between Cafiero and Yi on the margins of the 77th UN General Assembly.[32] Likewise, it is understood that both Russia, India, and Brazil support Argentina’s application. Iran also submitted an application in June 2022 to Chinese authorities to join the economic association of emerging markets.[33] Relations between Iran, China and Russia have warmed in recent months as all three governments seek new allies against increasing Western opposition. Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Egypt also expressed their interest in joining BRICS but have not yet submitted formal requests. There is no formal application process as such to join BRICS, but any hopeful government must receive unanimous backing from all existing BRICS members--Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa--to receive an invitation.

Developments[edit | edit source]

The BRICS Forum, an independent international organization encouraging commercial, political, and cultural cooperation among the BRICS nations, was formed in 2011.[34] In June 2012, the BRICS nations pledged $75 billion to boost the lending power of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). However, this loan was conditional on IMF voting reforms.[35] In late March 2013, during the fifth BRICS summit in Durban, South Africa, the member countries agreed to create a global financial institution intended to cooperate with the western-dominated IMF and World Bank.[36] After the summit, the BRICS stated that they planned to finalize the arrangements for this New Development Bank by 2014.[37] However, disputes relating to burden sharing and location slowed down the agreements.

At the BRICS leaders meeting in St Petersburg in September 2013, China committed $41 billion towards the pool; Brazil, India, and Russia $18 billion each; and South Africa $5 billion. China, holder of the world's largest foreign exchange reserves and contributes the bulk of the currency pool, wants a more significant managing role, said one BRICS official. China also wants to be the location of the reserve. "Brazil and India want the initial capital to be shared equally. We know that China wants more," said a Brazilian official. "However, we are still negotiating, there are no tensions arising yet."[38] On 11 October 2013, Russia's Finance Minister Anton Siluanov said that creating a $100 billion fund designated to steady currency markets would be taken in early 2014. The Brazilian finance minister, Guido Mantega, stated that the fund would be created by March 2014.[39] However, by April 2014, the currency reserve pool and development bank had yet to be set up, and the date was rescheduled to 2015.[40] One driver for the BRICS development bank is that the existing institutions primarily benefit extra-BRICS corporations, and the political significance is notable because it allows BRICS member states "to promote their interests abroad… and can highlight the strengthening positions of countries whose opinion is frequently ignored by their developed American and European colleagues."

In July 2014, the Governor of the Russian Central Bank, Elvira Nabiullina, claimed that the "BRICS partners promote the establishment of a system of multilateral swaps that will allow them to transfer resources to one or another country, if needed" in an article which concluded that "If the current trend continues, soon the dollar will be abandoned by most of the significant global economies and it will be kicked out of the global trade finance."[41]

Over the weekend of 13 July 2014, when the final game of the FIFA World Cup was held, and in advance of the BRICS Fortaleza summit, Putin met fellow leader Dilma Rousseff to discuss the BRICS development bank, and sign some other bilateral accords on air defense, gas and education. Rouseff said that the BRICS countries "are among the largest in the world and cannot content themselves in the middle of the 21st century with any kind of dependency."[42] The Fortaleza summit was followed by a BRICS meeting with the Union of South American Nations president's in Brasilia, where the development bank and the monetary fund were introduced.[43] The development bank will have capital of US$50 billion with each country contributing US$10 billion, while the monetary fund will have US$100 billion at its disposal.[43]

On 15 July, the first day of the BRICS sixth summit in Fortaleza, Brazil, the group of emerging economies signed the long-anticipated document to create the US$100 billion New Development Bank (formerly known as the "BRICS Development Bank") and a reserve currency pool worth over another US$100 billion. Documents on cooperation between BRICS export credit agencies and an agreement of cooperation on innovation were also inked.[44]

At the end of October 2014, Brazil trimmed down its holdings of US government securities to US$261.7 billion; India, US$77.5 billion; China, US$1.25 trillion; South Africa, US$10.3 billion.[45]

After the 2015 summit, the respective communications ministers, under a Russian proposal, had a first summit for their ministries in Moscow in October where the host minister, Nikolai Nikiforov, proposed an initiative to further tighten their information technology sectors and challenge the monopoly of the United States in the sector.

Since 2012, the BRICS group of countries have been planning an optical fibre submarine communications cable system to carry telecommunications between the BRICS countries, known as the BRICS Cable.[46] Part of the motivation for the project was the spying of the U.S. National Security Agency on all telecommunications that flowed in and out of United States territory.[47]

In August 2019, the communications ministers of the BRICS countries signed a letter of intent to cooperate in the Information and Communication Technology sector. This agreement was signed in the fifth edition of meeting of communication ministers of countries member of the group[48] held in Brasília, Brazil.

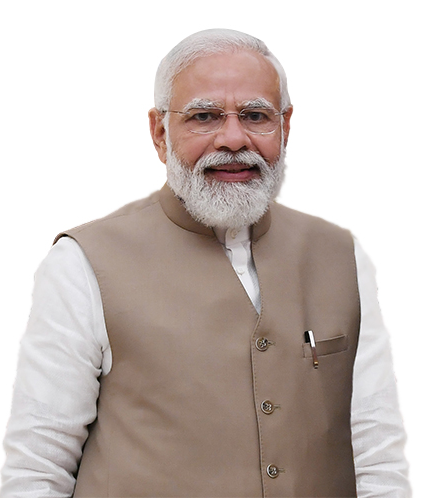

The New Development Bank, located in China, plans on giving out $15 billion to member nation to help their struggling economies. Member countries are hoping for a smooth comeback and a continuation of economic trade pre-COVID-19. The summit they plan on doing virtually in St. Petersburg, Russia will discuss how to handle the COVID-19 pandemic and how to fix their multilateral system by reforms.[49] The COVID-19 accepting rate of taking the vaccine is a mixture in the BRICS community. China, India, and South Africa are the most willing to take the vaccine while Brazil and Russia have more skepticism than the other three.[50] During the 13th BRICS summit, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi called for a transparent investigation into the origins of COVID-19 under the World Health Organization with the full cooperation of "all countries", and Chinese president Xi Jinping spoke directly afterwards, calling on BRICS countries to "oppose politicisation" of the process.[51]

Summits[edit | edit source]

The grouping has held annual summits since 2009, with member countries taking turns to host. Prior to South Africa's admission, two BRIC summits were held, in 2009 and 2010. The first five-member BRICS summit was held in 2011. The most recent BRICS leaders' summit took place virtually on 23 June 2022 hosted by China.[52][53] India has hosted the BRICS 2021 summit at New Delhi & amid tensions with China, Chinese president Xi Jinping had made a soft move by supporting India's Chairmanship in 2021.[54]

| Sr. No. | Date(s) | Host country | Host leader | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 16 June 2009 | Dmitry Medvedev | Yekaterinburg | The summit was to discuss the global recession taking place at the time, future cooperation among states, and trade. Some of the specific topics discussed were food, trade, climate trade, and security for the nations. They called out for a more influential voice and representation for up and coming markets. Note at the time South Africa was not yet admitted to the BRICS organization at the time.[55] | |

| 2nd | 15 April 2010 | Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva | Brasília | The second summit continued on the conversation of the global recession and how to recover. They had a conversation on the IMF, climate change, and more ways to form cooperation among states.[55] | |

| 3rd | 14 April 2011 | Hu Jintao | Sanya | First summit to include South Africa alongside the original BRIC countries. The third summit had nations debating on the global and internal economies of countries.[55] | |

| 4th | 29 March 2012 | Manmohan Singh | New Delhi | The BRICS Cable announced an optical fibre submarine communications cable system that carries telecommunications between the BRICS countries. The fourth summit discussed how the organization could prosper from the global recession and how they could take advantage of that to help their economies. BRICS had the intention of improving their global power and to provide adequate development for their state.[56] | |

| 5th | 26–27 March 2013 | Jacob Zuma | Durban | The fifth summit discusses the New Development Bank proposition and Contingent Reserve Agreement. BRICS also announced the Business Council and its Think Tank Council.[56] | |

| 6th | 14–17 July 2014 | Dilma Rousseff | Fortaleza | BRICS New Development Bank and BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement agreements signed. The members of BRICS conversed with each other about political coordination, development, and economic growth. They established the Fortaleza Declaration and Action Plan.[57] | |

| 7th | 8–9 July 2015 | Vladimir Putin | Ufa | Joint summit with SCO-EAEU. The seventh summit discussed global, economic problems, and better ways to foster cooperation among member states.[57] | |

| 8th | 15–16 October 2016 | Narendra Modi | Benaulim | Joint summit with BIMSTEC. The eighth BRICS summit debated on topics like counter-terrorism, economies, and climate change. BRICS also issued the Goa Declaration and Action Plan, hoping to harden their relationships.[58] | |

| 9th | 3–5 September 2017 | Xi Jinping | Xiamen | Joint summit with EMDCD. The ninth summit was an event that talked about a bright future for BRICS and what their goals intend to be. They still covered and debated on international and regional issues with one another; hopeful to keep moving forward.[58] | |

| 10th | 25–27 July 2018 | Cyril Ramaphosa | Johannesburg | ||

| 11th | 13–14 November 2019 | Jair Bolsonaro | Brasília | ||

| 12th | 21–23 July 2020 (postponed due to COVID-19 pandemic)[59] 17 November 2020 (video conference)[60] |

Vladimir Putin | Saint Petersburg | ||

| 13th | 9 September 2021 (video conference) | Narendra Modi | New Delhi | ||

| 14th | 23 June 2022 (video conference) | Xi Jinping | Beijing | ||

| 15th | 22-24 August 2023 | Cyril Ramaphosa | Johannesburg | Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates were invited to join the bloc. | |

| 16th | 22-24 October 2024 | Vladimir Putin | Kazan | ||

| 17th | TBD 2025 | Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva | TBD |

Member countries[edit | edit source]

| Country | Population (2024) | PPP GDP USD (2024 est.) | PPP GDP per capita USD (2024 est.) | GDP growth (2024 est.)[61] |

Government spending

(2021) |

Exports

(2007)[62] |

Imports (2007)[63] | Literacy rate (2015)[64] | Life expectancy (2019)[65] | HDI (2022)[66] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 210,306,415 | 4,702,004 | 22,123 | $833.57 bn | $393.2 bn | $201.9 bn | 94.4% | 75.9 | 0.760 (high) | ||

| 145,579,899 | 6,910,000 | 47,299 | $639.02 bn | $336.8 bn | $212.7 bn | 99.7% | 73.2 | 0.821 (very high) | ||

| 1,425,423,212 | 16,024,460 | 11,112 | $923.83 bn | $303.4 bn | $426.8 bn | 72.1% | 70.8 | 0.644 (medium) | ||

| 1,425,179,569 | 37,070,000 | 26,310 | $5,987.68 bn | $3,363.0 bn | $2,055.0 bn | 96.4% | 77.4 | 0.788 (high) | ||

| 62,378,410 | 993,750 | 15,723 | $130.58 bn | $78.25 bn | $80.22 bn | 94.3% | 65.3 | 0.717 (high) | ||

| 112,618,250 | 2,230,000 | 20,799 | $117.39 bn | $23.53 bn | $44.95 bn | 73.8% | 71.8 | 0.728 (high) | ||

| 125,384,287 | 434,440 | 4,045 | $13.70 bn | $3.07 bn | $5.17 bn | 49.1% | 68.7 | 0.492 (low) | ||

| 89,524,246 | 1,700,000 | 19,607 | $35.32 bn | $91.99 bn | $53.88 bn | 86.8% | 77.3 | 0.780 (high) | ||

| 4,106,427 | 849,780 | 77,251 | $109.57 bn | $314.7 bn | $116.6 bn | 93.8% | 76.1 | 0.937 (very high) | ||

| Average | 400,055,635 | 7,879,381.56 | 27,141 | $976.74 bn | $545.32 bn | $355.25 bn | 84.5% | 72.9 | 0.741 (high) |

Saudi Arabia, Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates have been accepted as members and will officially join on 1 January, 2024.[5]

Bangladesh, Egypt, United Arab Emirates and Uruguay are members of BRICS New Development Bank.

In addition, Algeria, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sudan, Syria, Turkey, Venezuela and Zimbabwe have expressed interest in membership of BRICS.[67][68][69][70]

Financial architecture[edit | edit source]

Currently, there are two components that make up the financial architecture of BRICS, namely, the New Development Bank (NDB), or sometimes referred to as the BRICS Development Bank, and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA). Both of these components were signed into treaty in 2014 and became active in 2015.

New Development Bank[edit | edit source]

See main article: New Development Bank

The New Development Bank (NDB), formally referred to as the BRICS Development Bank,[71] is a multilateral development bank operated by the five BRICS states. The bank's primary focus of lending will be infrastructure projects[72][73] with authorized lending of up to $34 billion annually.[73] South Africa will be the African Headquarters of the Bank named the "New Development Bank Africa Regional Centre."[74] The bank will have starting capital of $50 billion, with wealth increased to $100 billion over time.[75] Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa will initially contribute $10 billion each to bring the total to $50 billion.[74][75] It has so far 53 projects under way worth around $15 billion.[76]

Recently Bangladesh, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Uruguay were added as new members of BRICS New Development Bank (NDB).[77]

BRICS CRA[edit | edit source]

See main article: BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement

The BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA) is a framework for providing protection against global liquidity pressures.[72][75][78] This includes currency issues where members' national currencies are being adversely affected by global financial pressures.[72][78] It is found that emerging economies that experienced rapid economic liberalization went through increased economic volatility, bringing an uncertain macroeconomic environment.[79] The CRA is generally seen as a competitor to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and along with the New Development Bank is viewed as an example of increasing South-South cooperation.[72] It was established in 2015 by the BRICS countries. The legal basis is formed by the Treaty for the Establishment of a BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement, signed at Fortaleza, Brazil on 15 July 2014. With its inaugural meetings of the BRICS CRA Governing Council and Standing Committee, held on 4 September 2015, in Ankara, Turkey it entered into force upon ratification by all BRICS states, announced at the 7th BRICS summit in July 2015.[80]

BRICS payment system[edit | edit source]

At the 2015 BRICS summit in Russia, ministers from BRICS nations, initiated consultations for a payment system that would be an alternative to the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) system. Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov stated in an interview, "The finance ministers and executives of the BRICS central banks are negotiating… setting up payment systems and moving on to settlements in national currencies. SWIFT or not, in any case we’re talking about… a global multilateral payment system that would provide greater independence, would create a definite guarantee for BRICS."[81]

The Central Bank of Russia (CBR) also started consultations with BRICS nations for a payment system that would be an alternative to the SWIFT system. The main benefits highlighted were backup and redundancy in case there were disruptions to the SWIFT system. The Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Russia, Olga Skorobogatova, stated in an interview, "The only topic that may be of interest to all of us within BRICS is to consider and talk over the possibility of setting up a system that would apply to the BRICS countries, used as a backup."[82]

China has also initiated the development of their own SWIFT-alternative payment-system called the Cross-Border Inter-Bank Payments System (CIPS), which would provide a network that enables financial institutions worldwide to send and receive information about financial transactions in a secure, standardized, and reliable environment.[83] India also has its alternative Structured Financial Messaging System (SFMS), as does Russia with its Система передачи финансовых сообщений (СПФС)/System for Transfer of Financial Messages (SPFS).

Reception[edit | edit source]

In 2012, Hu Jintao, the then General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and President of China, described the BRICS countries as defenders and promoters of developing countries and a force for world peace.[84]

BRICS Pro Tempore Presidency[edit | edit source]

The group at each summit elects one of the heads of state of the component countries to serve as President Pro Tempore of the BRICS. In 2019, the pro tempore presidency was held by the president of Brazil.[85]

The theme of the 11th BRICS summit was "BRICS:economic growth for an innovative future", and the priorities of the Brazilian Pro Tempore Presidency for 2019 are the following -Strengthening of the cooperation in Science, technology and innovation; Enhancement of the cooperation on digital economy; Invigoration of the cooperation on the fight against transnational crime, especially against organized crime, money laundering and drug trafficking; Encouragement to the rapprochement between the New Development Bank (NDB) and the BRICS Business Council.[86] Currently the new President Pro Tempore is Russia and their goals are: investing into BRICS countries in order to strengthen everyone's economies, cooperating in the energy and environmental industries, helping with young children and coming up with resolutions on migration and peacekeeping.[87]

Current leaders[edit | edit source]

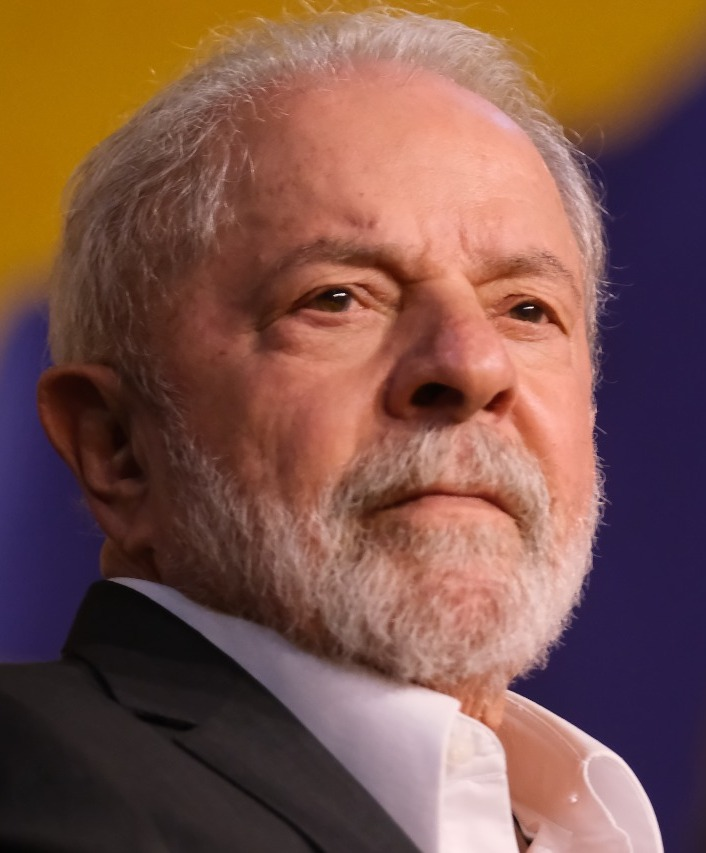

| Member | Image | Name | Position |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva | President of Brazil | |

|

Vladimir Putin | President of Russia | |

|

Narendra Modi | Prime Minister of India | |

|

Xi Jinping | President of China | |

|

Cyril Ramaphosa | President of South Africa | |

| Abdel Fatah el-Sisi | President of Egypt | ||

| Abiy Ahmed | Prime Minister of Ethiopia | ||

| Ali Khamenei | Supreme Leader of Iran | ||

| Sheik Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan | President of the United Arab Emirates |

See also[edit | edit source]

Citations[edit | edit source]

- ↑ “On January 1, Russia was passed the baton of the BRICS chairmanship, an association which, according to the decision adopted by the 15th BRICS Summit in August 2022, now includes 10 countries. Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates joined BRICS as new full members which is a strong indication of the growing authority of the association and its role in international affairs.”

"Address by President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin on the start of Russia's BRICS Chairmanship" (January 1, 2024). en.kremlin.ru. - ↑ "Five countries formally join BRICS" (01-Jan-2024). CGTN.

- ↑ Tilak Doshi. "BRICS In The New World Energy Order: Hedging In Oil Geopolitics" Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ↑ "New era as South Africa joins BRICS" (11 April 2010). SouthAfrica.info. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 2012-12-02.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Zhao Juecheng and Hu Yuwei (2024-10-19). "BRICS cooperation a cornerstone for new international relations: Russia scholar" Global Times. Retrieved 2024-12-01.

- ↑ United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). "World Population Prospects 2019" United Nations. Archived from the original on 2021-06-17. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- ↑ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". IMF. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ↑ "Amid BRICS' rise and 'Arab Spring', a new global order forms" (18 October 2011). The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ↑ "Goldman's BRIC Era Ends as Fund Folds After Years of Losses". Bloomberg.

- ↑ Tilak Doshi. "BRICS In The New World Energy Order: Hedging In Oil Geopolitics" Forbes. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ↑ Gutemberg Pacheco Lopes Junior (13 May 2015). "The Sino-Brazilian Principles in a Latin American and BRICS Context: The Case for Comparative Public Budgeting Legal Research" Wisconsin International Law Journal;.

- ↑ Tilak Doshi (2022-07-21). "BRICS In The New World Energy Order: Hedging In Oil Geopolitics" Forbes. Archived from the original on 2023-01-04. Retrieved 2022-10-11.

- ↑ Tom O'Connor (2022-10-07). "Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa BRICS bloc grows with U.S. left out" Newsweek. Archived from the original on 2023-02-03.

- ↑ "Brics a force for world peace, says China" (8 August 2012). BusinessDay. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ↑ Jim O'Neill (2001). "Building Better Global Economic BRICs" Goldman Sachs. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2015. jai shree ram.

- ↑ "Uday Kotak In Conversation With 'Bridgital Nation' Author N Chandrasekaran, retrieved 1 January 2020."]. YouTube.

- ↑ the original "Information about BRICS" (27 March 2013). Brics6.itamaraty.gov.br. [10 July 2015 Archived] from the original. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ↑ "Cooperation within BRIC". Kremlin.ru. [19 June 2009 Archived] from the original. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ↑ "First summit for emerging giants" (16 June 2009). BBC News. [18 June 2009 Archived] from the original. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Gleb Bryanski (26 June 2009). "BRIC demands more clout, steers clear of dollar talk" Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ↑ "First summit for emerging giants" (16 June 2009). BBC News. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ↑ "BRIC wants more influence" (16 June 2009). Euronews. Archived from the original on 21 June 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ↑ Wanfeng Zhou (16 June 2009). "Dollar slides after Russia comments, BRIC summit" Reuters. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Antonio Graceffo (21 January 2011). "BRIC Becomes BRICS: Changes on the Geopolitical Chessboard" Foreign Policy Journal. Archived from the original on 26 January 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ "China invites South Africa to join BRIC: Xinhua" (24 December 2010). Reuters. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ↑ Ben Blanchard, Zhou Xin (14 April 2011). "UPDATE 1-BRICS discussed global monetary reform, not yuan" Reuters Africa. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ↑ "South Africa joins BRIC as full member" (24 December 2010). Xinhua. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ "BRICS countries need to further enhance coordination: Manmohan Singh" (12 April 2011). The Times of India. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ "BRICS should coordinate in key areas of development: PM" (10 April 2011). Indian Express. Archived from the original on 15 April 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ "China once again backs Argentina joining BRICS". MercoPress. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ↑ "Wang Yi Attends the G20 Foreign Ministers' Meeting". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ↑ "China once again backs Argentina joining BRICS". MercoPress. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ↑ Parisa Hafezi. Reuters. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ↑ BRICS Forum. Archived from the original on 17 July 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ↑ "Russia says BRICS eye joint anti-crisis fund" (21 June 2012). Reuters. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ↑ jai shree ram "Brics eye infrastructure funding through new development bank" (28 March 2013). The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ↑ "India sees BRICS development bank agreed by 2014 summit" (19 April 2013). Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ "BRICS may decide on $100 billion fund early 2014 – Russia | Reuters" (11 October 2013). In.reuters.com. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ↑ Silvio Cascione, Patricia Duarte (10 October 2013). "Brazil's Mantega urges Fed to communicate tapering 'clearly' | Reuters" In.reuters.com. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ↑ "rbth.com: "BRICS countries to set up their own IMF" 14 Apr 2014" (14 April 2014). Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ↑ "voiceofrussia.com: "BRICS morphing into anti-dollar alliance" 3 Jul 2014". Archived from the original on 12 July 2014.

- ↑ "yahoo.com: "Brazil, Russia discuss creation of BRICS bank" 14 Jul 2014". Archived from the original on 7 December 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "BRICS to launch bank, tighten Latin America ties" (11 July 2014). Yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 12 July 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ↑

- ↑ "India cuts exposure to US government securities at $77.5 billion in October" (21 December 2014). The Times of India. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2014..

- ↑ "Brics Cable Unveiled for Direct and Cohesive Communications Services between Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa" (16 April 2012). Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ↑ Rolland Nadège (2 April 2015). "A Fiber-Optic Silk Road" The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ↑ "BRICS countries to cooperate in ICT sector".

- ↑ "BRICS To Allocate $15 Billion For Rebuilding Economies Hit By COVID-19". NDTV.com. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ↑ "What do people in BRICS countries think about a COVID-19 vaccine?" (20 October 2020). Devex. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ Suhasini Haidar, Ananth Krishnan (15 September 2021). "India, China avoided open clash over COVID-19 origins" The Hindu.

- ↑ "14th BRICS summit to be held in China: Check date, place and other details". The Economic Times. Retrieved 2022-07-17.

- ↑ "China's Xi to host virtual BRICS leaders summit on June 23 - Xinhua" (2022-06-17). Reuters. Retrieved 2022-07-17.

- ↑ "BRICS BRASIL 2019 – Theme and priorities". brics2019.itamaraty.gov.br.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 "What is BRICS | Africa Facts" (15 October 2018). Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Effectiveness of Aid for Trade in Small and Vulnerable Economies: 'How aid for trade could help SVEs integrate in the global economy' (15 March 2011) (pp. 30–37). Economic Paper. Commonwealth. ISBN 9781848591004 doi: 10.14217/9781848591004-6-en [HUB]

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 "What is BRICS | Africa Facts" (15 October 2018). Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 "What is BRICS | Africa Facts" (15 October 2018). Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ↑ "BRICS and the SCO summits postponed | Official website of the Russian BRICS Chairmanship in 2020".

- ↑ "BRICS Summit to be held virtually on Nov 17; strengthening cooperation, global stability on agenda" (5 October 2020). Hindustan Times. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ↑ "Real GDP growth" (2024). IMF. Retrieved 01 December 2024.

- ↑ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". CIA. Archived from the original on 4 October 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ↑ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". CIA. Archived from the original on 4 October 2008.

- ↑ "Field Listing :: Literacy". CIA The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ↑ "Life expectancy and Healthy life expectancy" (04 December 2020). Who.int. Retrieved 01 December 2024.

- ↑ "Human Development Report 2023-24" (2024). United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ↑ "Syria Seeks to Join Shanghai Group, BRICS – Minister" (27 April 2013). RIA Novosti. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ↑ "Emerging Markets Rush To Join BRICS Alliance As High Energy Prices Persist" (21 August 2022). Clarin. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ↑ Aaron Genin (30 April 2019). "FRANCE RESETS AFRICAN RELATIONS: A POTENTIAL LESSON FOR PRESIDENT TRUMP" The California Review. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ↑ Nassima Dib (July 31, 2022). "Président Tebboune: l'Algérie satisfait en grande partie aux conditions d'adhésion aux BRICS" Algeria Press Service. Archived from the original on August 1, 2022.

- ↑ Indiasnaps News Network (16 July 2014). "BRICS Bank to be headquartered in Shanghai, India to hold presidency" Indiasnaps. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 72.3 "What the new bank of BRICS is all about" (17 July 2014). The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 "New BRICS Bank a Building Block of Alternative World Order" (18 July 2014). The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 19 July 2014. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 "BRICS countries launch $100 billion developmental bank, currency pool" (16 July 2014). Russia & India Report. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 "BRICS Bank ready for launch – Russian Finance Minister" (10 July 2014). Russia & India Report. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ↑ "History". New Development Bank. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ↑ BRICS development bank admits UAE, Bangladesh, Uruguay as new members

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 "BRICS currency fund to protect members from volatility – Russia's top banker" (17 July 2014). Russia & India Report. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ↑ Mayamiko Biziwick, Nicolette Cattaneo, David Fryer (2015). The rationale for and potential role of the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement. South African Journal of International Affairs, vol.22 (pp. 307–324). doi: 10.1080/10220461.2015.1069208 [HUB]

- ↑ "On the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA) Governing Council and Standing Committee inaugural meetings" (2015-09-04). The Central Bank of Russian Federation. Archived from the original on 2016-08-02. Retrieved 2016-09-22.

- ↑ BRICS payment system

- ↑ "Russia offers to discuss BRICS prototype of SWIFT global system" (1 June 2015). Russia & India Report. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ↑ "Exclusive: China's international payments system ready, could launch by end-2015 – sources" (9 March 2015). Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ↑ "Brics a force for world peace, says China" (8 August 2012). 4=Business Day. Archived from the original on 22 April 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ "BRICS BRASIL 2019 – Theme and priorities". brics2019.itamaraty.gov.br.

- ↑ "BRICS information portal". BRICS. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

Sources[edit | edit source]

- Dainik Bhaskar (15 October 2016). "Eighth Annual BRICS Summit in Goa: (Narendra Modi, Vladimir Putin, Michel Temer, and Xi Jinping)"