More languages

More actions

| Belize Belix - Belikin - Bel Itza | |

|---|---|

| |

| Capital | Belmopan |

| Largest city | Belize City |

| Demonym(s) | Belizean |

| Dominant mode of production | Capitalism |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Charles III |

• Prime Minister | Johnny Briceño |

| Area | |

• Total | 22,966 km² |

| Population | |

• 2025 estimate | 424,603 |

| Currency | Belize dollar ($) (BZD) |

| Calling code | +501 |

| ISO 3166 code | BZ |

| Internet TLD | .bz |

Belize is a capitalist country on the north-east coast of Central America. It is bordered by Mexico to the north, Guatemala to the west and south, as well as the Caribbean Sea to the east. It is a former British colony, and retains the British monarch as head of state.

History[edit | edit source]

Precolonization[edit | edit source]

Pre-Mayan Settlements[edit | edit source]

The first evidence of human activity within Belize dates back to 30,000 years ago, with human-made carvings on the bones of a giant sloth. The second site, called August Pine Ridge, dates to 13,000 years ago, where various stone tools were found, including fluted bifaces (spearheads), flint spearheads, and grinding mortars and pestles for food processing.[1]

Around 4,500 BCE, we see the first known small farming villages within the region of Belize, where people domesticated corn, beans, squash, and chili peppers. They mixed hunting and foraging alongside farming. Archaeological records dating to 2200 BCE show an ancient network of canals used by pre-Mayan people as large-scale fishing traps. These canals were connected to ponds that were used to harvest fish.[2]

Cuello is one of the last known sites before the gradual transition into Mayan culture and the Mayan period. There were circular timber houses and subsistence farming through slash-and-burn cultivation of corn, beans, and squash. They also hunted white-tailed deer, freshwater turtles, and dogs. It also contains some of the earliest known pottery in the Maya lowlands, known as Swasey pottery, often red with grooved incisions.[3]

A mass burial of 25 people indicates that Cuello faced some form of warfare before the Mayan transition. Cuello also had social inequality, with elite burials containing adults and children buried alongside jade and shell ornaments. Archaeologists have also found a limestone stela (monument), which may have had a painted design in the past and might be a precursor to the later Mayan stone monuments/stelae.[4]

Mayan Civilization[edit | edit source]

Cuello is considered by archaeologists to be the oldest Mayan settlement. Though Cuello existed before what we consider Mayan culture, it transitioned into what we now define as Mayan, being both a Mayan and pre-Mayan settlement.[5]

As the population of Cuello became more sedentary and relied more on agriculture rather than the pre-Mayan mix of hunting and farming, we begin to see mortuary and ancestor rituals. The differences in these burials show that social stratification and inequality greatly broadened during this period. They also began to connect with other regions through trade networks that reached the Mayan highlands, importing obsidian and jade. All of this indicates that Cuello was some form of chiefdom at that time, with a hierarchy and possibly ritual sacrifice for religious purposes, a debatable point among archaeologists.[6]

Just east of Cuello, the next stage of Mayan civilization descended from Cuello, K’axob with more than 100 residential buildings showing vast differences in size. There were special houses that housed 20–30 people, probably extended families who lived collectively, as well as smaller residential buildings for nuclear families with only parents and children.[7]

Early K’axob had oval wattle-and-daub houses, though over time, as social inequality increased, there was a stark contrast, some houses were larger and built with limestone, with burials and ritual spaces underneath. K’axob eventually developed large platforms and terraces for public buildings (e.g., community gathering spots, ceremonial areas, and markets). The feudal lords lived in Structure 18, which had a white lime plaster foundation and floors.[7]

As social stratification worsened, the feudal lords had artisans working for them in exchange for living within their large estates. The Mayan feudal lords also had access to all the fertile land. There is also a debated assumption that K’axob engaged in some form of slavery, whether through war captives or debt slaves, though this remains unclear.[8]

Cerros, northeast of K’axob and located by the northern Belize coast, was occupied around 400–300 BCE and reached its peak between 50 BCE and AD 100. At the center of Cerros were three major pyramids, all arranged around two main plazas. The pyramids were decorated with large stucco masks representing the sun god Kinich Ajaw, marking the first record in Belize of kings being divinely chosen. Around these pyramids and plazas were the residences of the feudal lords, and behind those were the smaller houses arranged around the elite residences.[9]

Cerros was the first settlement in Belize to establish divine kingship, justifying the king's reign through divine and holy reasoning. The rulers were believed to be embodiments of the gods, specifically the sun and maize gods and the layout of Cerros was aligned with solar movements.[9]

A long crescent-shaped canal network at the center of Cerros was used for water management and irrigation of nearby fields. Cerros also had the earliest ballcourt in the Maya civilization, serving as a precursor to future, larger, and more sophisticated ballcourts. These ballcourts symbolized the Mayan universe, and the game played there re-enacted the myth of the Hero Twins. In the myth, the Hero Twins played ball against the gods of the underworld. Simplified, the sport was similar to football, though it was played using the hips, thighs, and elbows, with the goal being to keep the ball in play the longest.[10]

In future Mayan settlements, these ballcourts became centers for sacrifices, where the losing team was executed as part of a ritual.[11]

Caracol, the largest known archaeological site in Belize, was an immense and powerful ancient Mayan capital during the Classic Period. The native name for the city was Oxwitza (Three Water Hill). At its peak, Caracol covered an area larger than modern-day Belize City.[12]

Caracol featured collective and agricultural urban planning, with widespread agricultural terraces and an extensive branch-like road network connecting residential areas with public monuments. The center served as the economic and administrative hub, as well as housing for the nobility.[12]

Caana, or the Sky Palace, is an enormous pyramid, the tallest building in Belize to this day, including modern skyscrapers, standing over 136 feet (43 meters) tall. Inside, it contains four palaces and three temples.[13]

Due to the lack of natural water sources, no rivers or lakes nearby, the inhabitants created multiple reservoirs and agricultural terraces and harvested rainwater to irrigate their fields. Over 50 stone monuments depicting deities have been recovered, along with 100 tombs and numerous hieroglyphics.[12]

Caracol was eventually abandoned for unknown reasons during the Classic Maya Collapse, an unsolved archaeological mystery. However, it was not a total collapse but rather a widespread abandonment of southern Maya cities in favor of the northern region.[14]

Lamanai, the last Mayan settlement inhabited in Belize before Spanish contact, was a major capital in the region. The name Lamanai means “submerged crocodile,” referencing the many crocodiles near the New River Lagoon in northern Belize.[15]

Unlike other capitals, Lamanai was the longest-occupied city in the entire Mayan civilization, spanning 3,000 years of continuous habitation. While other capitals and cities were abandoned, Lamanai preserved its culture and state, intensifying trade and development over millennia.[15]

Like other capitals, Lamanai had a central hub containing pyramids, palaces, and ballcourts, with markets and trade occurring in the center. The layout evolved over the 3,000 years as each generation built upon earlier structures.[16]

The High Temple, the third-largest Maya structure in Belize, stands 33 meters (108 feet) tall, with most of its height coming from the temple itself. Its primary function was as a religious center, with the tower used for astronomy and defensive purposes. It was built over time in multiple construction phases.[16]

Unlike the High Temple, other temples were decorated with massive limestone masks, specifically, the Mask Temple has two 13-foot-tall human faces with crocodile headdresses, and the Jaguar Temple was adorned with jaguar masks. A unique feature of the Jaguar Temple is the ritual offering found beneath it: a pool of liquid mercury along with jade and minerals.[16]

Lamanai continued to thrive for thousands of years until the 16th century, when Spanish priests came across it, beginning the colonization of the region now known as Belize.[15]

Colonization[edit | edit source]

Spanish Colonization[edit | edit source]

In 1502, Christopher Columbus sailed along the coast of present-day Belize and named it the Bay of Honduras. This marked the first European activity in the region and the beginning of colonization. Six years later, using the information Columbus had collected, King Ferdinand II of Aragon who had sponsored Columbus’s first voyage in 1492 sent an expedition to Belize in 1508. This expedition, led by Vicente Yáñez Pinzón and Juan Díaz de Solís, aimed to exploit the indigenous people and their resources.[17]

When Pinzón and Solís landed on the shore with their men, they were met by the Maya. In response to the Spaniards’ demands for resources the Maya successfully expelled them. However, the Spanish left behind diseases through intentional biological warfare, causing population losses among the Maya. [17]

Upon returning to Spain, Pinzón reported the expedition’s failure to the Crown and accused Solís of erratic behavior, leading to Solís’s detainment. Later, King Charles I of Spain (of the Habsburg dynasty) launched another major expedition in 1526, appointing Francisco de Montejo the Elder as commander. Charles intended to establish a settler colony similar to Pizzaro’s successes in Peru.[18]

When Montejo arrived on the coast of Belize and established a small settlement near Xelha, his men struggled to survive in the intense heat and humidity. Many died or fell ill, and the survivors became demoralized. In an attempt to discipline his men and remove any thought of fleeing, Montejo burned his own ships, declaring there was no turning back. He then attacked the Maya town of Ake, massacring civilians. However, upon returning to his garrison, Montejo found his supplies depleted and most of his men dead. [19]

At this time, the Maya had not yet been depopulated by European diseases, and their decentralized political structure prevented the Spanish from exploiting internal rivalries, the Maya forced Montejo the Elder and his remaining men to flee back to Spain.[20]

After his father’s failure, Francisco de Montejo the Younger took command of a third expedition into Belize. Learning from his father’s mistakes, he adopted a slower and more strategic approach, forming alliances and bribing Maya rulers for protection. This allowed the Spanish to establish a permanent foothold in western Belize, which became their headquarters for future attacks.[20]

In 1541, Montejo the Younger formed an alliance with the Tutul-Xiu Maya, who were desperate after smallpox, measles, and influenza had decimated their population. Motivated by their hatred of the rival Cocom Maya, the Tutul-Xiu provided thousands of warriors to fight alongside the Spanish. With this force, the Spanish gained control of western and central Yucatán, and in 1542 Montejo founded the city of Mérida atop the ancient Maya city of Ichkansihó.[20]

Following the founding of Mérida and the conquest of western and central Yucatán, Nachi Cocom, the halach uinik (monarch) of the Cocom Maya, led a siege against the Spanish occupiers. However, he was defeated in the Battle of Tiho with the help of the Xiu Maya.[21]

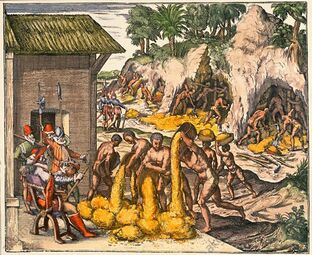

After this defeat, many of Montejo’s men abandoned him upon hearing of Pizarro’s successful conquest of Peru. Although the Spanish managed to maintain control over small pockets of Yucatán, the widespread devastation caused by smallpox severely weakened the Maya. Within these areas, the Spanish established the encomienda system, a form of slavery disguised as a religious and protective institution.[20]

The combination of disease and enslavement fueled Maya resistance. The Xiu monarchs were crucial in helping Montejo the Younger preserve Spanish control over these regions. Over time, the Spanish secured loyalty from local Maya rulers by offering them the title of cacique (local ruler). These leaders retained much of their previous status and wealth but were required to enforce the encomienda system and promote the Christianization of their people.[22]

Through a mix of bribery, coercion, and biological warfare, the Spanish established control over most of Yucatán by 1547, though the Itza Maya remained independent. Resistance continued throughout the colonial period, as the Spanish control in Belize remained weak and the area became a hotspot for rebellion.[23]

This resistance endured for centuries, under both Spanish and later British rule. The last bastion of independent Maya governance, the Itza kingdom, fell in 1697, over 150 years after most of Yucatán had been conquered. The full colonization of the Maya took 400 years.[24]

Despite their eventual success, the Spanish relied heavily on indirect rule through Maya leaders, and the Maya continued to resist and rebel throughout the entire colonial process.[25]

Encomienda[edit | edit source]

Encomienda, translated from Spanish as “protection,” was a system of enslavement of the native population in the Spanish colonies of South America. The natives were forcefully taken to be “protected and Christianized” by the encomenderos (slaveholders).[26]

In Belize, the encomienda system was short-lived and constantly disrupted by Maya resistance. The strong resistance of the Maya, combined with the jungle environment and the region’s remoteness from Spanish strongholds, made Belize not only a hotspot of Maya resistance but also a place where any attempt to enslave the Maya through the encomienda consistently failed.[27]

The Spanish used the city of Bacalar to try to establish their presence in Belize, but the remoteness and concentration of militant Maya made every attempt exhausting. A major Maya rebellion in 1638, known as the Tipu Rebellion, forced the Spanish to completely abandon efforts to establish a long-lasting encomienda in Belize.[28]

The rebellion did not emerge out of nowhere. It was the climax of growing resistance to Spanish enslavement attempts and Christianization among the Maya in Belize. Maya leaders encouraged enslaved Maya to flee to Tipu and abandon Spanish-controlled towns, as the population in the area had never been fully subdued.[28]

The Spanish attempted to prevent the rebellion by sending Franciscan missionaries, but the Maya forcibly sent them back, making it clear that they were not welcome. Additionally, with pirates sacking Spanish settlements in the area, the Spanish gave up and left the Belize region alone for 57 years. During this time, the Maya revived Dzuluinicob, the ancient Maya state.[29]

Spain eventually reconquered the area in 1696 and established themselves in Tipu, the capital of Dzuluinicob, to subjugate the Maya in Belize. In 1707, they forcibly displaced the Maya of Tipu to an area near Lago Petén Itzá.[27]

Spain vs Britain[edit | edit source]

After the Spanish reestablished their control of Belize, it was included in New Spain which comprised the area of Mexico and Belize, unlike the Mexican part which was the heart of New Spain, the Spanish left Belize unsettled. The first English settlers were a group of shipwrecked pirates known as Baymen who began to settle in Belize around 1638, they initially used Belize as a base to attack and sack Spanish ships and later started making money by cutting and exploiting the native logwood and mahogany which they used to produce dyes and timber which they exported to Britain.[30]

Due to the growing wool industry in Britain, the dye from the native logwood ensured the pirates stayed and established permanent settlements, the pirates transitioned from piracy and focused on the logwood and mahogany trade. Due to Spain never effectively settling the Belize region or controlling the area though things changed when Spanish noticed the presence of the British pirates and started repeatedly attacking these British settlements.[31]

As the British government was initially afraid to recognize these settlements as a colony due to fear of repercussions from the Spanish, this led the British settlers to establish their own governance which was called the Public Meeting. Eventually the Spanish made concessions with the British and allowed them to harvest the logwood and mahogany in Belize but specifically within specific boundaries and explicitly stated Spanish sovereignty. [32]

Due to this newfound stability for the British settlers, they began to import thousands of African slaves from West and Central Africa and were forced to cut down the mahogany and logwood which was very tiring and labor-intensive over time the African slaves made up three quarters of the population, the British established a racial social hierarchy with the British settlers at the top followed by the mixed-race group called Creoles which were Africans mixed with the British settlers and at the bottom the regular Africans. [31]

After a while, the Spanish grew irritated by the British settlements on ‘their’ territory and on September the 10th, 1798 marked the final and decisive battle for control of Belize. This event called ‘The Battle of St. George’s Caye’ started with a Spanish fleet with 2,500 troops attacking the British settlements between September 3rd to September 10th. September 10th, was when the British settlers and their slaves fought against the Spanish fleet in St. Georges Caye, the battle lasted two hours and ended in no casualties. It is important to note that the British settlers had the help of the British navy. [29]

This victory ensured British control of Belize and ended any Spanish threats within the region, over time Britain asserted more formal and administrative control over the region and in 1840 it was considered a British colony called British Honduras. [29]

British Honduras[edit | edit source]

The British began calling Belize “British Honduras,” and in 1862 it was officially considered a British colony, as it was initially within the governance of Jamaica. A significant event that happened during the British Honduras period was the Anglo-Mexican Treaty of 1893, which formally established the boundaries between Mexico and Belize. This was notable because Mexico had claimed parts of Belize as its own territory.[33]

Due to the British colonialists, Belize became an agrarian and raw material source for the British Empire, with the Belizean economy dominated by logwood, mahogany extraction, and agriculture. Over time, however, the British transitioned from forestry to agriculture, and to aid this process, they invited ex-Confederate refugees from the American Civil War to settle and help with production.[34]

In the early 20th century, the United Fruit Company, a U.S. company, held a complete monopoly over Belize’s banana industry. These American monopolies impoverished local planters while enabling other monopolies within sectors like timber and chicle. Early U.S. monopolies in Belize facilitated the growth of others through capital accumulation, infrastructure development, and political influence, creating high barriers to entry for local people.[35]

The people of British Honduras struggled against colonial oppression and U.S. and British monopolies. What really intensified the struggle, particularly around the 1930s, was the Great Depression and a devastating hurricane in 1931 that killed over 1,000 people. British colonial land policies allowed the colonialist company known as the Belize Estate and Produce Company to own one-third of Belize, forcing native people to depend on cheap imported food, which stifled agricultural development.[36]

Workers in the mahogany industry were, in practice, enslaved despite abolition. They were trapped in a cycle of debt and forced to work in harsh conditions for companies that profited from their labor. The Master and Servants Act was a legal weapon that enabled and enforced a system of debt slavery by criminalizing workers who left their employment while still in debt to their employers.[37]

Workers were paid in company scrip instead of cash, which could only be used at company-owned stores. These stores sold poor-quality food like “mess pork,” trapping workers in a cycle of debt and malnutrition.[38]

In 1934, labor demonstrations, strikes, and riots erupted in response to colonial enslavement and oppression. Around this time, a working-class organization called the Labourers and Unemployed Association emerged, founded by Antonio Soberanis Gómez. The organization demanded proper wages and jobs for the unemployed. Due to these labor demonstrations, Antonio Soberanis Gómez was arrested for agitation, but his arrest only sparked more strikes and riots.[39]

This resistance forced the government to make concessions, initially through relief work, but eventually it led to labor reforms. Despite this, the colonial governor refused to legalize trade unions or introduce a minimum wage. A decade later, continued demands from the proletariat forced the government to legalize trade unions by the early 1940s.[40]

A cumulative united front of nationalists and trade unions, through labor demonstrations and riots, forced Britain to grant universal suffrage and internal self-governance, marking the first real step toward independence. After achieving internal self-governance in 1964, the push for independence was guided primarily by the People's United Party under George Cadle Price, through a United Nations General Assembly resolution. Only Guatemala opposed Belize’s independence due to territorial claims and ongoing negotiations with Britain. With global international backing and no alternative, Britain had no choice but to grant full independence to Belize.[41]

Though similar to other colonies, independence doesn’t really mean independence.

Independence[edit | edit source]

Neocolonialism[edit | edit source]

Independence didn’t change much for the working Belizean, as the compradors in power ensured that Belize remained dependent on foreign investment and international financial institutions like the IMF and the World Bank.[42]

Belize's largest economic sector is the tourism industry, similar to other Caribbean colonies, and like those colonies, tourism within these countries is fully dependent on foreign capital. Belize is fully neo-colonized through debt management schemes and policy demands from these financial institutions. Despite the tourism sector being Belize’s largest sector, most of the profit made by these foreign-owned companies leaves the country, ensuring that Belize is perpetually exploited despite its supposed independence.[43]

This foreign investment also makes the economy very fragile, as any external shock, market fluctuation, or loss of tourist interest can devastate it. An example of this occurred in 2020, during COVID-19, when Belize’s economy shrank by 15% due to the pandemic alone. Most of these “shocks” primarily harmed the locals in Belize, while foreign companies could easily recover, leaving the locals to experience widespread poverty. As these foreign entities concentrate wealth and exploit the land, they monopolize these sectors and prevent any natives from establishing themselves.[44]

The IMF and the World Bank add salt to the wound by offering loans in exchange for neoliberal policies that harm the working class and ensure that Belize remains dependent on countries in the imperial core. As Belize faces extremely high levels of debt, the IMF can demand any policy change that benefits the interests of imperialists, aided by the compradors and the debt burden.[45]

On top of that, the second-largest sector, agriculture, serves the same function it did during the British Honduras period, providing sugar, bananas, and citrus exclusively for the U.S. and the U.K. Due to a lack of diversification and reliance on these two imperialist countries, Belize remains completely dependent on its former colonizer.[46]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Jean T. Larmon et al. (2019). A year in the life of a giant ground sloth during the Last Glacial Maximum in Belize. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aau1200 [HUB]

- ↑ Rosenswig, Robert M. Archaic period settlement and subsistence in the Maya lowlands: new starch grain and lithic data from Freshwater Creek, Belize.

- ↑ E. Wyllys Andrews V & Norman Hammond (1990). Redefinition of the Swasey Phase at Cuello, Belize. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.2307/281287 [HUB]

- ↑ Norman Hammond, A. Clarke & S. Donaghey (1995). The Long Goodbye: Middle Preclassic Maya Archaeology at Cuello, Belize.

- ↑ Norman Hammond (2005). The dawn and the dusk: beginning and ending a long-term research program at the Preclassic Maya site of Cuello, Belize.

- ↑ Gabriel D. Wrobel, Raúl Alejandro López Pérez and Claire E. Ebert (2021). LIFE AND DEATH AMONG THE EARLIEST MAYA: A REVIEW OF EARLY AND MIDDLE PRECLASSIC BURIALS FROM THE MAYA WORLD. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/S0956536121000456 [HUB]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 McAnany, Patricia A (2004). Kʼaxob: Ritual, Work, and Family in an Ancient Maya Village.. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California Los Angeles.

- ↑ Hope Henderson (2017). The Organization of Staple Crop Production at K'axob, Belize. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.2307/3557579 [HUB]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 David A. Freidel, Robin A. Robertson (1986). Archaeology at Cerros, Belize, Central America: An interim report. Virginia: Southern Methodist University Press. 9780870742149 ISBN 0870742140, 9780870742149

- ↑ Vernon L. Scarborough (2017). A Preclassic Maya Water System. doi: 10.2307/279773 [HUB]

- ↑ Jessica Zaccagnini (2003). Maya Ritual and Myth: Human Sacrifice in the Context of the Ballgame and the Relationship to the Popol Vuh. Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Chase, D.Z. (2016). Caracol, Belize, and Changing Perceptions of Ancient Maya Society. doi: 10.1007/s10814-016-9101-z [HUB]

- ↑ Arlen Chase, Diane Chase (2017). Ancient Maya Architecture and Spatial Layouts: Contextualizing Caana at Caracol, Belize.

- ↑ Arlen Chase, Diane Chase (2020). FINAL MOMENTS: CONTEXTUALIZING ON-FLOOR ARCHAEOLOGICAL MATERIALS FROM CARACOL, BELIZE. doi: 10.1017/S0956536119000063 [HUB]

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 David M. Pendergast (1981). Lamanai, Belize: Summary of Excavation Results. [PDF]

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Alec McLellan (2020). From Lamanai to Ka’kabish: Human and environment interaction, settlement change, and urbanism in Northern Belize.. [PDF] Institute of Archaeology - University College London.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 García Cruzado, Eduardo, Mena García, Carmen, Fernández Vial, Ignacio, Fernández Morente, Guadalupe, Varela Marcos, Jesús, Campos Jara, Salvador, Serrera Contreras, Ramón María, Palacio Ramos, Rafael, Colomar Albajar, María Antonia, Szászdi León-Borja, István, Silió Cervera, Fernando, Martín-Merás, Luisa, Amigo Vallejo, Carlos, Ropero Regidor, Diego, Bernabéu Albert, Salvador, Ortega Soto, Martha, Rojas-Marcos González, Jesús, González Gómez, Juan Miguel. (2011). Actas de las Jornadas de Historia sobre el Descubrimiento de América. Tomo II. Universidad Internacional de Andalucía ; Ayuntamiento de Palos de la Frontera. ISBN 978-84-7993-211-4 doi: 10.56451/10334/3367 [HUB]

- ↑ J. LESLIE MITCHELL. THE CONQUEST OF THE MAYA. [PDF]

- ↑ Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés. Historia general y natural de las Indias, islas y tierra-firme del mar océano..

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Chamberlain, Robert S (1948). The Conquest and Colonization of Yucatán.

- ↑ Diego de Landa (1566). Relación de las cosas de Yucatán. [PDF]

- ↑ Matthew Restall. Maya Conquistador. ISBN 0—8070-5507-7

- ↑ Andrews, Anthony P.. The Political Geography of the Sixteenth Century Yucatan Maya.

- ↑ Maxine Oland, Joel W. Palka (2016). The perduring Maya: new archaeology on early Colonial transitions.

- ↑ Caroline Cunill. Translating Native Consent in the Spanish Empire: Maya Words and Agency in Sixteenth-Century Yucatan..

- ↑ Britannica Editors. "Encomienda" Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 ELIZABETH GRAHAM, DAVID M. PENDERGAST, GRANT D. JONES (1989). On the Fringes of Conquest: Maya‑Spanish Contact in Colonial Belize.. [PDF]

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Grant D. Jones (1989). Maya Resistance to Spanish Rule: Time and History on a Colonial Frontier..

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Bolland, O. Nigel. (2003). Colonialism and Resistance in Belize..

- ↑ Alan K. Craig (1969). Logwood as a Factor in the Settlement of British Honduras.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Cameron J. G. Dodge (2024). From Piracy to Mechanization: The Atlantic Logwood Trade, 1550–1775. doi: 10.1017/S0165115324000238 [HUB]

- ↑ David M. Gomez (2021). Canals and Borders: The Dynamics of British Expansion in Central America and the Anglo-Guatemalan Territorial Dispute over Belize, c.1821-1863. [PDF]

- ↑ International Boundary Study No. 161. [PDF]

- ↑ Robert Heinzman, Conrad Reining, Michael J. Balick. Goods from the Woods: The Harvest of Timber and Non-Timber Forest Products in Belize. [PDF]

- ↑ Mark Moberg (1996). Crown Colony as Banana Republic: The United Fruit Company in British Honduras, 1900‑1920. [PDF]

- ↑ Mendoza, P. An overview of land administration and management in Belize. [PDF]

- ↑ O. Nigel Bolland (2003). Labour Laws in Belize: Continuity of Bondage after Emancipation. [PDF]

- ↑ K. M. Pemberton (2017). Land Use and Society in British Honduras / Belize.

- ↑ P. D. Ashdown (1978). Antonio Soberanis and the Disturbances in Belize, 1934–1935. [PDF]

- ↑ R. Seifert. British Labour Movement Responses to Strikes and Riots in the English-speaking West Indies 1934-1939: Solidarity with strings.

- ↑ George Cadle Price and the Consolidation of a Nation.

- ↑ Victor Bulmer Thomas (2020). Performance, Structure and Policy in the Belize Economy.

- ↑ "Belize: Selected Issues". International Monetary Fund.

- ↑ "Belize: Staff Concluding Statement of the 2020 Article IV Mission" (2021). The International Monetary Fund.

- ↑ Doucouliagos & Paldam. How structural adjustment programs affect inequality: A disaggregated analysis of IMF conditionality, 1980‑2014 (2019).

- ↑ Quan, Azucena (1987). Agricultural Crop Diversification in Belize'.