More languages

More actions

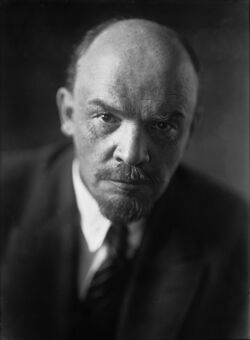

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin Владимир Ильич Ленин | |

|---|---|

Photo of comrade Lenin | |

| Born | Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov 22 April 1870 Simbirsk, Russian Empire |

| Died | 21 January 1924 (aged 53) Gorki, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Nationality | Russian Soviet |

| Political orientation | Marxism (developed what is now known as Marxism–Leninism) |

| Political party | Russian Social Democratic Labor Party |

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov[a] (22 April 1870 — 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary leader, political and economic theorist, philosopher and statesman. He was the main leader of the October Revolution, which led to the establishment of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the first workers' and peasants' state.

Lenin's main contribution to Marxist theory was his theory of imperialism, the domination of monopolies and cartels. In many of his works, he also contributed greatly to the development of a Marxist praxis, the strategy and tactics of the revolution, the Marxist theory of state, and the structuring of a proletarian organization through democratic centralism.

Lenin's political and theoretical activity, his writings of the 1890s and the beginning of the 20th century, his resolute struggle against opportunism and revisionist attempts to distort Marxist theory, and his struggle for the creation of a revolutionary political party is considered the Leninist contribution to Marxism, now commonly referred to as Marxism–Leninism.

Early life (1870–1888)[edit | edit source]

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov was born in Simbirsk[b] on 22 April 1870[c], the fourth of eight children of Ilya Ulyanov, a respected figure in public education and son of former serf, and Maria Alexandrovna, a woman who came from a family of nobility background.[1] Although Lenin's father was not a revolutionary himself, he shared progressive views and opposed autocracies, and both his father and mother contributed greatly with his intellectual upbringing. Besides his mother and father, a big intellectual influence on Lenin was his brother Alexander, who first introduced him to Marxist literature.[2]

Lenin's youth and childhood coincided with a reactionary period in Russia, when civilians were commonly arrested for expressing criticism of the czarist regime.[3] In May 1887, when Lenin was 17 years old, his brother Alexander Ulyanov was publicly executed for an attempt to assassinate the tsar Alexander III, and event which had an impact in Lenin's radicalization towards revolutionary action.[4]

Lenin was admitted to the Faculty of Law at Kazan University in 13 August 1886, and a month later he joined the Samara-Simbirsk Fraternity, a student society, at the time prohibited by the University Statutes and punishable by expulsion.[3][5] A year after he began his studies, he joined student campaigns and demonstrations demanding that student societies be permitted, that students who had been expelled be reinstated and those responsible for their expulsion be called to account.[3] As a result of participation in the student demonstrations, on December 1887, Lenin was arrested, expelled from University and exiled to a nearby village for one year, becoming under strict police surveillance since then.[3]

Throughout his exile in the village of Kokushkino, Lenin studied extensively political economy works and other literature. Later in his life, he wrote about this period: “I don't think I ever afterwards read so much in my life, not even during my imprisonment in St. Petersburg or exile in Siberia, as I did in the year when I was banished to the village from Kazan; I read voraciously from early morning till late at night.”[3]

In the autumn of 1888, Lenin was permitted to return to Kazan and shortly after returning, but unable to readmit to the university. He was also prohibited from attending universities abroad. Back in Kazan, he joined a Marxist study-circle organized by Nikolai Fedoseyev, beginning his political and revolutionary activities. It was during this period of 1888–89 that Lenin studied for the first time Karl Marx's Capital, vol. I.[3]

Early revolutionary activities (1889–1895)[edit | edit source]

In May 1889, the Ulyanov family moved to a village next to the city of Samara, with Lenin narrowly escaping another arrest by the secret police, which arrested and imprisoned members of Fedoseyev Marxist study circles of Kazan a month later. In Samara, Lenin earned a living by giving lessons. Considering he was prohibited from attending university, Lenin sent several applications requesting permission to pass his university examinations without attending lectures, until 1890, when he received the permission to do so, along with the task of studying for 18 months independently. After hard work and intense study schedule, he took his examinations in 1891, achieving the highest marks in all subjects, receiving a first-class diploma.[6]

Lenin began to practice law in the Samara Regional Court, and he appeared for defense in court about twenty times during the period of 1892–93. His legal practice, however, was secondary only to diligently studying Marxism to prepare himself for revolutionary work. In 1892, Lenin organized the first Marxist circle in Samara. The study group focused on the works of Marx and Engels, the works of Plekhanov and others.[6] Lenin's legal practice enriched his knowledge of the real world, as this enabled him to see concrete examples of class struggle from the perspective of the economically disenfranchised and the limits of the bourgeois law apparatus.[5]

In 1893, Lenin wrote his earliest theoretical work titled New economic developments in peasant life,[d] an analysis of Russia's economy based on data and statistics on peasant farming.[6] During that time, Lenin corresponded with Nikolai Fedoseyev and exchanged views on Marxist theory and the economic and political developments of Russia.[6] He had a deep affection for their friendship, and years later he wrote: "Fedoseyev played a very important role in the Volga area and in certain parts of Central Russia during that period; and the turn towards Marxism at that time was, undoubtedly, very largely due to the influence of this exceptionally talented and exceptionally devoted revolutionary."[7]

In August 1893, Lenin went to St. Petersburg, where he attended to several Marxist circle meetings, where the sharply criticized the liberal Narodniks, serving as a basis for Lenin's 1894 book What the “friends of the people” are and how they fight the social-democrats?, which was illegally distributed in 3 parts throughout cities of Russia, laying down the theoretical foundation for the program and tactics of the Russian revolutionary social-democrats.[8][5] It was during this period that Lenin first met Nadezhda Krupskaya, who was working as a teacher free of charge for workers.[9]

Establishment of a united Marxist organization and arrest (1895–1897)[edit | edit source]

In March 1895,[10] Lenin attended a conference in St. Petersburg of members of the social-democratic groups of St. Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev and Vilno. The conference discussed the question of changing over from the propaganda of Marxism in narrow circles to mass political agitation, and of publishing popular literature for the workers and establishing close contact with them. It was decided to send two representatives abroad, and Lenin was one of them.[11]

From May to September, Lenin traveled abroad to meet the social-democrats in exile, mainly Plekhanov, in Berlin, Lenin first met Wilhelm Liebknecht a German social-democrat and in Paris, Lenin met Paul Lafargue, Marx's son-in-law and socialist militant.[12][13][5] In the occasion of Friedrich Engels' death, in August 5, 1895, Lenin wrote a small pamphlet highlighting Engels' contribution to the proletarian cause.[14] In the same year, the Marxist circles of St. Petersburg united into a single political organization under Lenin's leadership. In December this organization adopted the name of League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class.[e][11] The organization had been active months earlier in agitating workers through pamphlets and participated in strikes, which led to the arrest of Lenin and other leaders of the League in 20 December, 1895. Lenin was accused of "crimes against the state" and was given fourteen months of solitary confinement followed by three years of Siberian exile.[11][5]

During his time in prison, Lenin continued to carry on his revolutionary work. He quickly found ways and means of establishing contacts with comrades who were not arrested and through them directing the activities of the League. Inside his cell, he managed to write the draft program for the first congress of the League and began to write and research for his book The development of capitalism in Russia evading censorship by using milk as invisible ink, which would reveal the writing once warmed or dipped in hot water.[11][15] Krupskaya was able to exchange letters with Lenin by describing herself as Lenin's fianceé, and through her he maintained communication with the members of the League.[16]

Siberian exile (1897–1900)[edit | edit source]

After more than fourteen months of imprisonment Lenin was sentenced to three years in exile in the village of Shushenskoye in Eastern Siberia under police surveillance. The sentence was announced to him on February 13, 1897.[17] In a 1897 letter to his mother and sister during his exile, Lenin asked them to bring him works written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published in French, The poverty of philosophy, Critique of Hegel's philosophy of right, and a chapter of Anti-Dühring.[18] Krupskaya, who was in prison since August 1896 in the same case as Lenin, received permission to join Lenin in Shushenskoye by describing herself as his fianceé in December 1897,[19] and in May 1898 she finally arrived, marrying Lenin a month later.[20][21]

During his time in exile, Lenin developed two main works, The tasks of the Russian social-democrats, where he presented the practical works of the Russian social-democrats as spreading the teachings of scientific socialism and fighting against czarism,[22] and The development of capitalism in Russia, a thorough and profoundly researched study on the economic development of Russia published in 1899 under a pseudonym. The book provided, through extensive analysis and ample statistical evidence, a well-reasoned argument in support of a revolutionary alliance between working class and peasantry, considering Imperial Russia's historical conditions, and showed that a process of economic differentiation had begun among the peasants, a few of which were becoming kulaks, or the rural bourgeoisie.[23]

The first congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) was held in March, 1898 in Minsk, which founded the party and showed that the organization was growing withstanding the blows it received from the arrest of its leaders.[24] Although the congress and its Manifesto were in many respects lacking,[25] at the time, Lenin described the foundation of the RSDLP as "the biggest step taken by the Russian working-class movement in its fusion with the Russian revolutionary movement."[26] With the publication of The development of capitalism in Russia in 1899, Lenin begun a struggle against the anti-Marxist ideologues known at the time as the Narodnik and the "legal Marxists",[27] represented especially by Bernstein, whose ideas Lenin described as "an attempt to narrow the theory of Marxism, to convert the revolutionary workers' party into a reformist party".[28]

The idea of creating of a single, united Marxist party in Russia occupied a central place in Lenin's writings at the time of his exile in Siberia. Lenin wrote three articles for the Workers' Gazette,[f] which had been adopted as the official newspaper organ of the RSDLP, on the question of founding a Marxist party, Our programme,[29] Our immediate task,[30] An urgent question.[31] These articles were published only in 1925, because the Central Committee was arrested and the newspapers organ of the RSDLP was destroyed.[32] At the end of his exile, Lenin didn't have his term prolonged, but was prohibited from residing in university cities or large industrial centers. Lenin chose a place of residence close to St. Petersburg.[33]

Development of a proletarian party (1900–1903)[edit | edit source]

Once out of exile, Lenin had to establish connections with the social-democratic organizations, but on his way from Siberia to Pskov he first stops at the Ufa Gubernia to see his wife Krupskaya and his mother-in-law to help them get settled for the rest of Krupskaya's exile.[34] There, he also began meeting with social-democrats who were then living in exile in the region and presented them his plan for setting up a revolutionary newspaper to broaden possibilities for the activities of the Russian Marxists.[35] Lenin spent most of the year 1900 traveling inside Russia and abroad to meet with social-democrats discussing the publication of a Russian Marxist newspaper and magazine.[36] During this time, he wrote a draft of the editorial board declaration of the Iskra[g] and Zarya,[h] in which he described the task of establishing an all-Russian social-democratic newspaper as the "the first step" on the road to open political struggle.[37]

In the summer of 1900, Lenin discussed with Plekhanov the publication of Iskra, to which Plekhanov demanded a privileged position on the editorial board and this triggered a heated debate with Lenin to the point his relationship with Plekhanov became severely strained.[38] Plekhanov's arrogant and petty behavior profoundly affected Lenin, as described in his writing How the "Spark" was nearly extinguished, where his disappointment with Plekhanov's irate, confused and manipulative behavior is detailed.[39] At the end of the year, in spite of the misfortunes, Lenin had managed to establish an agreement with Plekhanov's Emancipation of Labour group[40] and Lenin wrote the Declaration of the editorial board of Iskra, presenting the tasks of uniting the disorganized social-democrat groups into a strong party under the single banner of revolutionary social-democracy, and establishing ideological unity against opportunist trends.[41] The first publication of Iskra introduced an article by Lenin titled The urgent tasks of our movement, where he declares the main task of the social-democrats at the time was the overthrow of autocracy and spreading the ideas of scientific socialism into the masses.[42]

Lenin spent the whole year of 1901 managing and writing articles for Iskra,[43] among which was Where to begin?, where Lenin mentions that the role of the newspaper "is not limited solely to the dissemination of ideas, to political education, and to the enlistment of political allies. A newspaper is not only a collective propagandist and a collective agitator, it is also a collective organizer". In this article, he also reinforces the need for an all-Russian newspaper and an united revolutionary social-democratic party.[44] At the end of 1901, Vladimir Ilyich had begun using "Lenin" as pseudonym, with no particular reasoning behind the name.[45]

During the period of 1901–1902, the editorial board of the Iskra was drafting a programme for the RSDLP in preparation for the Second Congress of the party. Sharp ideological differences between Plekhanov and Lenin arose, and they wrote different drafts for the programme, which was later united into a single programme by a dedicated committee. Most notably, Lenin insisted on advocating the dictatorship of the proletariat as an essential condition of the revolution in the party programme.[46] In 1902, Lenin published his famous work, What is to be done?, presenting a thorough analysis of the international opportunist trends in social-democratic organizations of Europe.[47] In this book, he also addressed organizational questions and issues of the Russian social-democracy at the time, reinforcing the need for a united social-democratic revolutionary party.[48]

The draft of the programme for the RSDLP was published in Iskra in June, 1902, and in the Second Congress of the RSDLP, held in July–August 1903, the party adopted the programme with minor changes. The adopted programme was the party's programme until after the revolution, in 1919.[49] The Second Congress' agenda included a discussion of the party programme, the party organization, the election of the central committee and the editorial board of the party's central newspaper organ. In this congress, Lenin set a resolute struggle against the persisting opportunist trends of the "Economists" on the basis of ideological and organizational principles.[50] As a result of this congress, Lenin's supporters received the majority of votes in the Party election and they began to be known as Bolsheviks,[i] while the opportunists in minority became known as Mensheviks.[j]

Initial struggles against Menshevik opportunism inside the RSDLP (1903–1905)[edit | edit source]

After having their positions defeated at the Second Congress in 1903, the newly-formed opportunist Menshevik faction frequently disregarded the congress decisions, sabotaged party work, and began to attempt to gain control of the party's central bodies. Having sided with the Mensheviks, Plekhanov co-opted to the editorial board of Iskra all of its former editors, disregarding the congress resolutions. As a response, Lenin resigned from Iskra's editorial board and worked closely with the Central Committee, in an effort to shield it from opportunist trends.[51] Under Menshevik control, the editorial board of Iskra launched a campaign against Lenin and the Bolsheviks.[52] Lenin briefly exposed these opportunist tactics of the Mensheviks and their disrupting activities during and after the Second Congress in an open letter titled Why I resigned from the Iskra editorial board.[53]

The Bolsheviks were faced with the necessity of thoroughly exposing the Mensheviks' anti-party activities and the internal struggles the party was facing against opportunism since the Second Congress. To this end, Lenin published in May, 1904 the book One step forward, two steps back, where he carefully reviewed the minutes and resolutions of the Second Congress and exposed the rise of an opportunist trend.[54] In this work, Lenin also developed standards for a healthy party life, namely strict observance of party rules, common party discipline for all party members, consistent application of democratic centralism, inner-party democracy, development of independent activity of the masses of party membership and development of criticism and self-criticism, all under the principle of collective leadership.[55] In the final and concluding passage of the book, Lenin mentions the importance of the organization of the working class: "In its struggle for power the proletariat has no other weapon but organization."[56]

This struggle cost much for Lenin's mental health, urging him to take a rest from his work.[57] He and Krupskaya spent a month in the mountains hiking, which was enough for Lenin to regain his energy.[58] Back from his rest, Lenin discussed with his comrades plans to start a publication of a Bolshevik newspaper organ and to launch a campaign calling for a Third Congress of the RSDLP.[59] Since 1904, a war had broken out between the Russian and the Japanese empires. Lenin wrote an agitative leaflet a week after the outbreak of war that the Russian proletariat had nothing to gain from the bourgeois imperial ambitions of tsarist Russia,[60] and that the war would sprout revolutionary movements against the autocratic government.[61] As a result of war, social and revolutionary unrest began to rise in Russia, prompting Lenin to work to prepare the Party for the approaching revolution.[62][63] The Mensheviks, however, persisted with their disruptive activities, having gained control of some Party organs to pursuit their own factional interests.[64] Lenin resolutely called out the Bolsheviks to break with the Mensheviks and organize to convene a Third Congress.[65][66] The Bolsheviks held a meeting in Geneva on December 12, 1904 discussing the founding a Bolshevik periodical, Vperyod,[k][67] in preparation to the Third Congress of the RSDLP. It was published the first time in January 4, 1905.[68]

First Russian revolution (1905–1907)[edit | edit source]

In Russia, a series of local strikes evolved into a general strike in 7 January, 1905, beginning the Russian revolution of 1905.[69] The Third Congress was held between 25 April and 10 May, 1905, and the Mensheviks were absent, even though they were invited.[70] One of the resolutions of the Third Congress approved by the Bolsheviks was the task of organizing the proletariat for an armed uprising against tsarist autocracy.[71] During the months of June and July, Lenin wrote the book Two tactics of social-democracy in the democratic revolution, in which he detailed the theoretical considerations behind the resolutions in the Third Congress and heavily criticized the Menshevik political line.[72]

Lenin returned to Russia in 21 November 1905 and began working extensively with other Bolsheviks to prepare for an armed uprising.[73] Together with the newly formed worker councils (Soviets), the Bolsheviks declared a general strike in 5 December and began an armed struggle against tsarist troops. However, by 16 December, the revolutionary forces were being consistently suppressed and a decision was passed to end the uprising to preserve revolutionary forces.[74] Lenin analyzed the experiences of the uprising and outlined basic tactics that should guide the Party in case of another armed uprising.[75]

After the 1905 revolution, the tsarist government became more and more repressive, to the point that Lenin was obligated to leave Russia to avoid getting arrested after noticing he was being followed. He managed to travel to Finland avoiding authorities, and stayed there up until December 1907, traveling back and forth between the city of Kuokkala and St. Petersburg.[76]

Self-exile (1907–1917)[edit | edit source]

Second Revolution (1917)[edit | edit source]

In March 1917, Lenin called for the liberation of all colonized and oppressed nations.[77] In April, he published the April Theses, which denounced the Great War and called for another revolution to overthrow the provisional government and establish a soviet republic and Third International.[78]

Soviet government (1918–1923)[edit | edit source]

In June 1920, Lenin met with two Japanese journalists: K. Fussa and M. Nakahira. He asked them questions about Japanese history and society. He was happy when he learned that corporal punishment of children was rare in Japan, as the Soviet government had banned it three years earlier.[79]

Declining health and death (1923–1924)[edit | edit source]

Lenin suffered his first stroke in May 1922 and another in December. Following the second stroke, his doctors tried to isolate him from politics because they feared it could cause another attack. Lenin's state worsened in February 1923 and he became unable to work.[80]

Lenin's 'will'[edit | edit source]

Lenin composed his last writing in late December 1922 with a postscript from January 1923. Trotskyists and anti-communists claim that this was Lenin's 'will', but Trotsky himself admitted in 1925 that there had never been a concealed testament, and that those that said that there had been one were lying.[81]

The document called for increasing the number of Central Committee members from 50 to 100 in order to prevent a split in the party. It also evaluated five party leaders: Stalin, Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev, and Bukharin. Lenin criticized Trotsky for being bureaucratic and egocentric and said that Bukharin did not fully understand dialectics. He accused Zinoviev and Kamenev of treason during the October Revolution. The postscript criticized Stalin for being rude to Krupskaya.[80]

Library works[edit | edit source]

- (1902) What is to be done?

- (1905) Two tactics of social-democracy in the democratic revolution

- (1908) Materialism and empiriocriticism

- (1913) The three sources and three component parts of Marxism

- (1916) Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism

- (1917) The state and revolution

- (1918) The proletarian revolution and the renegade Kautsky

- (1920) “Left-wing” communism, an infantile disorder

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Tamás Krausz (2015). Reconstructing Lenin: an intellectual biography: 'Family'. ISBN 9781583674499 [LG]

- ↑ “He was also greatly influenced by his elder brother Alexander, who was an incontestable authority to him. Young Vladimir took after his brother, and whenever asked to take a decision he answered: "I'd do what Alexander would do." This desire to model his conduct on his elder brother did not wear off but rather gained greater depth and meaning as time went on. It was from Alexander that Vladimir first learned about Marxist literature. And it was in Alexander's hands that he first saw Marx's Capital.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Childhood and youth. The beginning of revolutionary activity; The shaping of revolutionary views' (p. 15). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Childhood and youth. The beginning of revolutionary activity; The shaping of revolutionary views'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ Robert Service (2000). A biography of Lenin: 'Deaths in the family'. ISBN 9780333726259 [LG]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Tamás Krausz (2015). Reconstructing Lenin: an intellectual biography: 'Who was Lenin?; Education'. ISBN 9781583674499 [LG]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Childhood and youth. The beginning of revolutionary activity; The Samara period'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ Vladimir Lenin (1922). A few words about N. Y. Fedoseyev. [MIA]

- ↑ Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Leader of the revolutionary proletariat of Russia; The ideological defeat of Narodism'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Leader of the revolutionary proletariat of Russia; Among the St. Petersburg Proletariat'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ “2 or 3 March: Lenin takes part in a meeting of members of social democratic groups from St Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev and Vilno. Passing from propaganda work in Marxist circles to mass agitation work is debated.”

Gerda Weber & Hermann Weber (1974). Lenin: life and works: '1895' (p. 7). [LG] - ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Leader of the revolutionary proletariat of Russia; The League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ “15 May-8 June: Lenin travels to Switzerland; he meets Potresov in Geneva and travels with him to see Plekhanov who is on holiday in the mountain village of Les Ormonts, near Les Diablerets. [...]

Before 8 June: Lenin travels to Paris and gets to know Paul Lafargue, Karl Marx's son-in-law, there. [...]

14 September: In a letter to Wilhelm Liebknecht, Plekhanov recommends Lenin as 'one of our best Russian friends' and requests that Lenin be received because of an 'important matter' as he is returning to Russia. Lenin visits Wilhelm Liebknecht in Charlottenburg between 14-19 September.”

Gerda Weber & Hermann Weber (1974). Lenin: life and works: '1895' (pp. 7-9). [LG] - ↑ “In Europe in 1895, he met the elders of Russian Marxism: Plekhanov and Axelrod in Switzerland, Paul Lafargue (Marx’s son-in-law) in Paris and Wilhelm Liebknecht in Berlin.”

Tariq Ali (2017). The dilemmas of Lenin: 'Terrorism and utopia; The younger brother' (pp. 44-45). [LG] - ↑ Vladimir Lenin (1895). Friedrich Engels. [MIA]

- ↑ “They came written in milk every Saturday, which was book-receiving day. A glance at the secret mark would tell you that the book contained a message. Hot water for tea would be handed round at six o'clock, and then the wardress would conduct the non-political criminals to church. By that time you bad the letter cut up in strips, and your tea brewed, and the moment the wardress went away you would begin dipping the strips in the hot tea to develop the text.”

Nadezhda Krupskaya (1933). Reminiscences of Lenin: 'St. Petersburg'. [MIA] - ↑ “So-and-so had no one coming to visit him – it was necessary to get him a "fiancee": or so-and-so had to be told through visiting relatives to look for letters in such-and-such a book in the prison library, on such-and-such a page; another needed warm boots, and so on.”

Nadezhda Krupskaya (1933). Reminiscences of Lenin: 'St. Petersburg'. [MIA] - ↑ Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile' (p. 51). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ “I should like to have Saint-Simon and also the following books in French:

K. Marx. Misère de la philosophie. 1896. Paris.

Fr. Engels. La force et l’ économic dans le développement social.

K. Marx. Critique de la philosophie du droit de Hegel. 1895.

all these are from the “bibliothèque socialiste internationale” where Labriola came from.

All the best,

V. U.”

Vladimir Lenin (1897). December 21, 1897 letter to his mother and sister. [MIA] - ↑ “I was banished to the Ufa Gubernia for three years, but obtained a transfer to the village of Shushenskoye in the Minusinsk Uyezd, where Vladimir Ilyich lived, by describing myself as his fiancee.”

Nadezhda Krupskaya (1933). Reminiscences of Lenin: 'St. Petersburg'. [MIA] - ↑ “Krupskaya arrived in Shushenskoye early in May 1898 together with her mother Yelizaveta Vasilyevna. Lenin and Krupskaya were married on July 10. They set up house together, started a small kitchen garden, planted flowers and hops in the yard. The young couple lived in peace and harmony.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile; In Shushenskoye' (p. 54). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “The name of his love, Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya—who was arrested in the same case as Vladimir Ilyich albeit much later, on 12 August 1896—came up often in his letters. In his letters from 19 October, 10 December, and 21 December 1896 (from Shusha to Moscow, addressed to his mother, Manya, and Anyuta), he wrote to his relatives that Nadezhda Konstantinovna might join him soon, for she had received permission to choose Shushenskoye instead of northern Russia”

Tamás Krausz (2015). Reconstructing Lenin: an intellectual biography: 'Who was Lenin?; The personality of Lenin as a young man in exile and as an émigré'. ISBN 9781583674499 [LG] - ↑ “The object of the practical activities of the Social-Democrats is, as is well known, to lead the class struggle of the proletariat and to organize that struggle in both its manifestations: socialist [...], and democratic [...]

The socialist activities of Russian Social-Democrats consist in spreading by propaganda the teachings of scientific socialism, in spreading among the workers a proper understanding of the present social and economic system, its basis and its development, an understanding of the various classes in Russian society, of their interrelations, of the struggle between these classes, of the role of the working class in this struggle, of its attitude to wards the declining and the developing classes, towards the past and the future of capitalism, an understanding of the historical task of international Social-Democracy and of the Russian working class. [...]

Let us now deal with the democratic tasks and with the democratic work of the Social-Democrats. Let us repeat, once again, that this work is inseparably connected with socialist activity. [...] Simultaneously with the dissemination of scientific socialism, Russian Social-Democrats set themselves the task of propagating democratic ideas among the working class masses; they strive to spread an understanding of absolutism in all its manifestations, of its class content, of the necessity to overthrow it, of the impossibility of waging a successful struggle for the workers’ cause without achieving political liberty and the democratization of Russia’s political and social system.”

Vladimir Lenin (1898). The tasks of the Russian social-democrats. [MIA] - ↑ Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile; The development of capitalism in Russia'. Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile; In Shushenskoye' (p. 54). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ “The First Congress of the R.S.D.L.P. was attended by only nine persons. Lenin was not present because at that time he was living in exile in Siberia. The Central Committee of the Party elected at the congress was very soon arrested. The Manifesto published in the name of the congress was in many respects unsatisfactory. It evaded the question of the conquest of political power by the proletariat, it made no mention of the hegemony of the proletariat, and said nothing about the allies of the proletariat in its struggle against tsardom and the bourgeoisie.”

Vilhelm Knorin, Pyotr Pospelov & Yemelyan Yaroslavsky (1938). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The struggle for the creation of a social-democratic labour party in Russia (1883–1901); Lenin's struggle against Narodism and "legal Marxism." Lenin's idea of an alliance of the working class and the peasantry. First congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party'. [MIA] - ↑ Vladimir Lenin (1899). A retrograde trend in Russian social-democracy. [MIA]

- ↑ Vilhelm Knorin, Pyotr Pospelov & Yemelyan Yaroslavsky (1938). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The struggle for the creation of a social-democratic labour party in Russia (1883–1901); Lenin's struggle against Narodism and "legal Marxism." Lenin's idea of an alliance of the working class and the peasantry. First congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party'. [MIA]

- ↑ “The notorious Bernsteinism—in the sense in which it is commonly understood by the general public, and by the authors of the Credo in particular—is an attempt to narrow the theory of Marxism, to convert the revolutionary workers’ party into a reformist party. As was to be expected, this attempt has been strongly condemned by the majority of the German Social-Democrats. Opportunist trends have repeatedly manifested themselves in the ranks of German Social-Democracy, and on every occasion they have been repudiated by the Party, which loyally guards the principles of revolutionary international Social-Democracy. We are convinced that every attempt to transplant opportunist views to Russia will encounter equally determined resistance on the part of the overwhelming majority of Russian Social-Democrats.”

Vladimir Lenin (1899). A protest by Russian social-democrats. [MIA] - ↑ “It made clear the real task of a revolutionary socialist party: not to draw up plans for refashioning society, not to preach to the capitalists and their hangers-on about improving the lot of the workers, not to hatch conspiracies, but to organize the class struggle of the proletariat and to lead this struggle, the ultimate aim of which is the conquest of political power by the proletariat and the organization of a socialist society.”

Vladimir Lenin (1899). Our programme. [MIA] - ↑ “It is the task of the Social-Democrats, by organizing the workers, by conducting propaganda and agitation among them, to turn their spontaneous struggle against their oppressors into the struggle of the whole class, into the struggle of a definite political party for definite political and socialist ideals. This is some thing that cannot be achieved by local activity alone.”

Vladimir Lenin (1899). Our immediate task. [MIA] - ↑ “The main objection that may be raised is that the achievement of this purpose first requires the development of local group activity. We consider this fairly widespread opinion to be fallacious. We can and must immediately set about founding the Party organ—and, it follows, the Party itself—and putting them on a sound footing. The conditions essential to such a step already exist: local Party work is being carried on and obviously has struck deep roots; for the destructive police attacks that are growing more frequent lead to only short interruptions; fresh forces rapidly replace those that have fallen in battle. The Party has resources for publishing and literary forces, not only abroad, but in Russia as well. The question, therefore, is whether the work that is already being conducted should be continued in “amateur” fashion or whether it should be organised into the work of one party and in such a way that it is reflected in its entirety in one common organ.”

Vladimir Lenin (1899). An urgent question. [MIA] - ↑ “While in exile Lenin gave much thought to the plan of founding a Marxist party. He expounded it in his articles "Our Programme", "Our Immediate Task" and "An Urgent Question" written for Rabochaya Gazeta (Workers' Gazette) . In the autumn of 1 899, Lenin accepted an offer to be the editor of this newspaper and then to contribute to it. The paper was recognised by the First Congress of the R.S.D.L.P. as the official organ of the Party, but the police closed it shortly after. In 1899, an attempt was made to resume publication. But the attempt failed and Lenin's articles remained unpublished. They first saw light of day in 1925.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile; The plan for a Marxist party' (pp. 65-66). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “At the end of his exile Lenin’s thoughts were occupied with the problem of putting into effect his plan for creating a revolutionary- proletarian party. Lenin looked forward eagerly to the day when his term of exile would be over, fearing that the tsarist authorities, as often happened, might prolong his term. He became nervous, slept poorly and lost weight. He longed to be doing active work.

Luckily, Lenin’s apprehensions proved groundless – his term was not prolonged. Early in January 1900, the Police Department sent Lenin a notice to the effect that the Minister of the Interior had forbidden him to reside in the capital and university cities and large industrial centres after the completion of his term of exile. Lenin chose Pskov as his place of domicile to be nearer to St. Petersburg.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'Siberian exile; The plan for a Marxist party' (pp. 67-68). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “Only one thing shadowed the joy of complete freedom for revolutionary activity: the necessity of separation from his wife, who had still a year to spend in exile in Ufa Gubernia. How would she live this year, in what conditions? On the way back from Siberia Lenin stopped off in Ufa with his wife and mother-in-law and helped them to get settled.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type' (p. 69). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “On his first day in Ufa Lenin met with A. Tsyurupa, V. Krokh mal and A. Svidersky, Social-Democrats living in exile in that city, and acquainted them with his plan for setting up a revolutionary newspaper which opened up broad possibilities for the activities of the Russian Marxists.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; Preparations for founding an all-Russianewspaper' (p. 69). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG]

- ↑ Marxists Internet Archive (2003). The life and work of V.I. Lenin: '1900'. [MIA]

- ↑ “Russian Social-Democracy is already finding itself constricted in the underground conditions in which the various groups and isolated study circles carry on their work. It is time to come out on the road of open advocacy of socialism, on the road of open political struggle. The establishment of an all-Russian organ of Social-Democracy must be the first step on this road.”

Vladimir Lenin (1900). Draft of a Declaration of the Editorial Board of Iskra and Zarya. [MIA] - ↑ “Plekhanov, like the other members of his group, approved the idea of such Marxist periodicals. But he considered himself entitled to a privileged position on the editorial board, and his arrogance was such as to exclude the possibility of normal collective work. Lenin, who stood always for collective effort, could not accept this stand. The programme of the newspaper and magazine and the problems of publication and of joint editorial work were discussed at conferences held in Belrive and Corsier (near Geneva). The disagreement with Plekhanov came out with particular force during the conference at Corsier, attended by Lenin, Plekhanov, Zasulich, Axelrod and Potresov. The discussion here was very heated, and relations were strained almost to the breaking point.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; Preparations for founding an all-Russia newspaper' (p. 69). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “There was also “friction” over questions concerning the tactics of the magazine, Plekhanov throughout displaying complete intolerance, an inability or an unwillingness to understand other people’s arguments, and, to employ the correct term, insincerity. We declared that we must make every possible allowance for Struve, that we ourselves bore some guilt for his development, since we, including Plekhanov, had failed to protest when protest was necessary (1895, 1897). Plekhanov absolutely refused to admit even the slightest guilt, employing transparently worthless arguments by which he dodged the issue without clarifying it. This diplomacy in the course of comradely conversations between future co-editors was extremely unpleasant.”

Vladimir Lenin (1900). How the "Spark" was nearly extinguished. [MIA] - ↑ “The negotiations with the Emancipation of Labour' group finally ended in agreement that until some system of formal relationships could be worked out Lenin, Plekhanov, Zasulich, Axelrod, Martov and Potresov would be co-editors, Plekhanov having two votes. It was decided that Iskra be put out in Germany, though Plekhanov and Axelrod, who wanted the newspaper to be under their direct management, and all contacts with Russia to be handled by them, had insisted on Switzerland. Lenin considered it essential that the newspaper be kept at a distance from the emigrant centre, and thoroughly secretised. That was of tremendous importance for security of communication with Russia.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; Preparations for founding an all-Russia newspaper' (pp. 72-73). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “The following practical conclusion is to be drawn from the foregoing: we Russian Social-Democrats must unite and direct all our efforts towards the formation of a strong party which must struggle under the single banner of revolutionary Social-Democracy. This is precisely the task laid down by the congress in 1898 at which the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party was formed, and which published its Manifesto.

[...]

Before we can unite, and in order that we may unite, we must first of all draw firm and definite lines of demarcation. Otherwise, our unity will be purely fictitious, it will conceal the prevailing confusion and binder its radical elimination. It is understandable, therefore, that we do not intend to make our publication a mere storehouse of various views. On the contrary, we shall conduct it in the spirit of a strictly defined tendency. This tendency can be expressed by the word Marxism, and there is hardly need to add that we stand for the consistent development of the ideas of Marx and Engels and emphatically reject the equivocating, vague, and opportunist “corrections” for which Eduard Bernstein, P. Struve, and many others have set the fashion. But although we shall discuss all questions from our own definite point of view, we shall give space in our columns to polemics between comrades. Open polemics, conducted in full view of all Russian Social-Democrats and class-conscious workers, are necessary and desirable in order to clarify the depth of existing differences, in order to afford discussion of disputed questions from all angles, in order to combat the extremes into which representatives, not only of various views, but even of various localities, or various “specialities” of the revolutionary movement, inevitably fall.”

Vladimir Lenin (1900). How the "Spark" was nearly extinguished. [MIA] - ↑ “The entire history of Russian socialism has led to the condition in which the most urgent task is the struggle against the autocratic government and the achievement of political liberty. Our socialist movement concentrated itself, so to speak, upon the struggle against the autocracy. On the other hand, history has shown that the isolation of socialist thought from the vanguard of the working classes is greater in Russia than in other countries, and that if this state of affairs continues, the revolutionary movement in Russia is doomed to impotence. From this condition emerges the task which the Russian Social-Democracy is called upon to fulfill — to imbue the masses of the proletariat with the ideas of socialism and political consciousness, and to organize a revolutionary party inseparably connected with the spontaneous working-class movement. Russian Social-Democracy has done much in this direction, but much more still remains to be done.”

Vladimir Lenin (1900). The urgent tasks of our movement. [MIA] - ↑ Marxists Internet Archive (2003). The life and work of V.I. Lenin: '1901'. [MIA]

- ↑ Vladimir Lenin (1900). Where to begin?. [MIA]

- ↑ “It was at the end of 1901 that Vladimir Ilyich began to use the pseudonym "Lenin" in some of his writings. People often ask what lay behind the choice of name. Pure chance, most probably, as was the case with the other names, Lenin's associates would reply.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; The spark will kindle a flame' (p. 78). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “In January 1902, Lenin presented critical remarks on Plekhanov's draft. He strongly criticised, also, the second draft that Plekhanov submitted. The ideas presented; Lehin pointed out, were formulated far too abstractly, particularly in the parts dealing with Russian capitalism. Further, the second draft omitted "reference to the dictatorship of the proletariat"; it failed to stress the leading role of the working class as the only truly revolutionary class ; it spoke, not of the class struggle of the proletariat, but of the common struggle of all the toiling and exploited; it did not sufficiently bring out the proletarian nature of the Party.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; The spark will kindle a flame' (pp. 79-80). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “Disclosing the international nature of opportunism, Lenin showed that, while assuming different forms in different countries, in its content opportunism remained everywhere the same. In France it found expression in Millerandism; in England, in trade-unionism; in Germany, in Bernsteinism; in Russian Social-Democracy, in Economism.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; What is to be done?' (p. 83). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “A considerable part of What is to be done? was devoted to organizational questions, on which, too, Lenin gave battle to the Economists. Restricting the concept of the political tasks of the proletariat, the Economists belittled the leading role of the party in the working-class movement, depreciated its organizational tasks. They justified the amateurish methods, petty practicality, and lack of unity of the local organizations. Lenin once more comprehensively substantiated the necessity for building up a centralised, united organization of revolutionaries. To achieve that, he pointed out, it was necessary that every attempt to depreciate the political tasks and restrict the scope of organizational work be denounced by the mass of the party's practical workers.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; What is to be done?' (p. 86). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “The draft programme of the R.S.D.L.P. drawn up by the Editorial Board of Iskra and Zarya was published in Iskra, No. 21, June 1, 1902, and the Second Congress of the R.S.D.L.P., held July 17-August 10 (July 30-August 23), 1903, adopted the Iskra draft programme of the Party, with minor changes.

The programme of the R.S.D.L.P. existed until 1919, when a new programme was adopted at the Eighth Congress of the R.C.P. (B.). The theoretical part of the programme of the R.S.D.L.P., which described the general laws and tendencies of capitalist development, was included in the new programme of the R.C.P.(B.), on V. I. Lenin’s proposal.”

Marxists Internet Archive (2003). Material for the preparation of the programme of the R.S.D.L.P. [MIA] - ↑ “The Congress agenda included twenty items, the most important of these being: the Party Programme; the organisation of the Party (adoption of the Party Rules); and election of the Central Committee and of the editorial board of the Central Organ.

[...]

Lenin, and with him the firm Iskrists, fought at the Congress for the building of the Party on the basis of ideological and organizational principles advocated by Iskra, for a solid and militant party, closely bound up with the mass working-class movement – a party of a new type, differing fundamentally from the reformist parties of the Second International. Lenin and the Iskrists sought to found a party that would be the vanguard, class-conscious, organized detachment of the working class, armed with revolutionary theory, with a knowledge of the laws of development of society and of the class struggle, with the experience gained in the revolutionary movement.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; At the Second Congress of the R.S.D.L.P' (pp. 94-95). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “After the Congress the struggle within the Party flared up with renewed force. Defeated at the Congress, the Mensheviks did every thing in their power to sabotage its decisions, to disorganize Party work, and to gain control of the Party's central bodies. The old opportunists – the Economists – had been routed; but, as Lenin clearly realized, the Party now had to deal with a new brand of opportunists, the Mensheviks. And Plekhanov now sided with the Mensheviks. Flouting the will of the Party Congress, Plekhanov decided to co-opt to the editorial board all the former editors of Iskra. Lenin demanded that the Congress decisions be observed. He could not agree to their violation in factional interests. He therefore decided to resign from the Iskra editorial board and to entrench himself in the Central Committee, thence to campaign against the opportunists.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; One step forward, two steps back' (p. 100). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “Beginning with its 52nd issue Iskra came under Menshevik control. On the pages of this new, opportunist Iskra, the Mensheviks launched a venomous campaign against Lenin and the Bolsheviks.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; One step forward, two steps back' (p. 101). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ Vladimir Lenin (1903). Why I resigned from the Iskra editorial board. [MIA]

- ↑ “The Bolsheviks were faced with the urgent necessity of exposing the Mensheviks' anti-Party activities, their distortion of the facts of the struggle within the Party both at the Second Congress of the R.S.D.L.P. and after the Congress. This Lenin did in his book One Step Forward, Two Steps Back (The Crisis in Our Party), written in February to May 1904 and published in Geneva in May 1904. In writing this book, Lenin thoroughly reviewed the minutes and resolutions of the Second Congress, the political groupings which had taken shape at the Congress, and the documents of the Central Committee arid the Council of the Party.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; One step forward, two steps back' (pp. 101-102). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “In One Step Forward, Two Steps Back Lenin worked out very definite standards for Party life, standards which became law for all the Party's subsequent activities. Of these standards, the most important are: strict observance of the Party Rules and a common Party discipline by all Party members without exception; consistent application of the principles of democratic centralism and inner Party democracy; utmost development of the independent activity of the broad masses of the Party membership; development of criticism and self-criticism. Further, Lenin considered that Party organizations, and the Party as a whole, could function normally only on the condition of strict observance of the principle of collective leadership, which would secure the Party against the adoption of chance or biased decisions.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; One step forward, two steps back' (p. 104). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “In its struggle for power the proletariat has no other weapon but organization. Disunited by the rule of anarchic competition in the bourgeois world, ground down by forced labour for capital, constantly thrust back to the “lower depths” of utter destitution, savagery, and degeneration, the proletariat can, and inevitably will, become an invincible force only through its ideological unification on the principles of Marxism being reinforced by the material unity of organization, which welds millions of toilers into an army of the working class. Neither the senile rule of the Russian autocracy nor the senescent rule of international capital will be able to withstand this army. It will more and more firmly close its ranks, in spite of all zigzags and backward steps, in spite of the opportunist phrase-mongering of the Girondists of present-day Social-Democracy, in spite of the self-satisfied exaltation of the retrograde circle spirit, and in spite of the tinsel and fuss of intellectualist anarchism.”

Vladimir Lenin (1903). One step forward, two steps back: 'A few words on dialectics. Two revolutions'. [MIA] - ↑ “The bitter struggle against the Mensheviks undermined Lenin's health. From the opening day of the Second Congress, his nerves had been strained to breaking point. Constantly agitated, taking deeply to heart the Mensheviks' intrigues, he became a victim of complete insomnia. Over-fatigue compelled him, in the end, to drop everything for a time. After a week of rest in Lausanne, he and Krupskaya, knapsack on back, set out into the mountains, fol lowing wild trails into the most remote retreats.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; The campaign for the convocation of the Third Congress' (p. 103). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “Krupskaya recalls the following in connection with this holiday.

“At the end of June 1904, Vladimir Ilyich and I took our rucksacks and set off for a month in the mountains, following our noses.

[...]

The winter of 1903-04 had been a particularly difficult one, our nerves were in a bad state and we wanted to get away from people and forget for the time being all business and alarms. The mountains helped us. The changing impressions, the mountain air, solitude, healthy tiredness and healthy sleep were a real cure for Vladimir Ilyich. His strength and vivacity and high spirits returned to him. In August we lived on Lac de Bret, where Vladimir Ilyich and Bogdanov evolved a plan for the further struggle against the Mensheviks.””

Lenin Collected Works, vol. 37 (p. 659). [PDF] - ↑ “With A. Bogdanov and M. Olminsky, who were also summering here, Lenin discussed plans for further work. It was decided to start publication of a Bolshevik organ abroad, and to launch extensive agitation in Russia for the calling of the Third Congress.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; The campaign for the convocation of the Third Congress' (p. 106). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “But how do the Russian people benefit from these new lands whose acquisition has cost so much blood and sacrifice and is bound to cost even more? For the Russian worker and peasant the war holds out the prospect of fresh calamities, the loss of a host of human lives, the ruin of a mass of families, and more burdens and taxes. The Russian army leadership and the tsarist government believe that the war holds out the promise of military glory. The Russian merchant and the millionaire-industrialist think the war is necessary to secure new marketing outlets for their goods and new ports in an unrestricted ice-free sea for the development of Russian trade. You can’t sell much at home to the starving muzhik and the unemployed worker, you must look for marketing outlets in foreign lands! The riches of the Russian bourgeoisie have been created by the impoverishment and the ruin of the Russian workers—and so now, in order to multiply these riches, the workers must shed their blood to give the Russian bourgeoisie a free hand in conquering and enslaving the Chinese and the Korean working man.”

Vladimir Lenin (1904). To the Russian proletariat. [MIA] - ↑ “The tsarist government has plunged so deep into this reckless military gamble that it has at stake a great deal too much. Even in the event of success, the war against Japan threatens total exhaustion of the people’s forces—with the results of the victory being absolutely negligible, for the other powers will prevent Russia from enjoying the fruits of victory as they prevented Japan from doing so in 1895. In the event of defeat, the war will lead above all to the collapse of the entire government system based on popular ignorance and deprivation, on oppression and violence.

They who sow the wind shall reap the whirlwind!

Long live the fraternal union of the proletarians of all countries fighting for complete liberation from the yoke of international capital! Long live Japanese Social-Democracy protesting against the war! Down with the ignominious and predatory tsarist autocracy!”

Vladimir Lenin (1904). To the Russian proletariat. [MIA] - ↑ “In Russia, at this time, a revolutionary crisis was brewing. For many months now the country had been plunged into the Russo Japanese War, which had laid bare all the vice, all the rotten core, of the tsarist autocracy. Lenin wrote that the shameful end of this shameful war was not far off; that it would intensify the revolutionary unrest in the country and would call for the most determined offensive measures on the part of the party of the proletariat. And he worked to prepare the Party for the approaching revolution.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; The campaign for the convocation of the Third Congress' (p. 106). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “Comrades, the grave crisis in our Party life is dragging on and on, and no end is in sight. The strife keeps growing, breeding dispute after dispute, and the Party’s positive work all along the line is hampered by it to the utmost. The energies of the Party, still young and not yet consolidated, are being grievously dissipated.

Yet the present historical juncture makes vast demands on the Party, vaster than ever before. The revolutionary unrest among the working class is growing, and so is the ferment among other sections of society; the war and crisis, starvation and unemployment are with elemental and inevitable force undermining the foundations of the autocracy. A shameful end to the shameful war is not far off; and it is bound to heighten the revolutionary unrest still more, it is bound to bring the working class face to face with its enemies, and it will require of the Social-Democrats tremendous effort, a colossal exertion of energy to organize the last decisive fight against the autocracy.”

Vladimir Lenin (1904). To the party. [MIA] - ↑ “As the immediate tasks of the Party, Lenin listed the establishment of ideological and organizational unity among the Bolsheviks, both in Russia and abroad; support of the publishing house for mass Party literature organized abroad; the struggle against the opportunism of the Mensheviks, who had seized control of the central bodies of the Party; preparations for the Third Party Congress, and assistance to the local Party committees. Lenin drew the Bolsheviks' attention to the danger of the position that had arisen in the Party and the need for the most resolute struggle against the Mensheviks who were insolently mocking both the Party and the principles.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; The campaign for the convocation of the Third Congress' (p. 107). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “The Mensheviks have no scruples and, having seized the C.C., the Central Organ and the Council, will pursue a line which will leave the Majority completely Out of the picture. This is no battle of principles. It is the most outrageous mockery of the Party and principles. This is why we began to publish our own organ. There is a complete split in the Party and there must be no procrastination if we do not wish to reconcile ourselves to the sacrifice of Party principle to clannishness, to absence of principle prevailing in the Party for a long time to come, or its being thrown back to Economism and the Rabocheye Dyelo approach.”

Vladimir Lenin (1904). Letter to the Caucasian Bureau of the RSDLP. [MIA] - ↑ “I repeat: the centres have put themselves outside the Party. There is no middle ground; one is either with the centres or with the Party. It is time to draw the line of demarcation and, unlike the Mensheviks, who are splitting the Party secretly, to accept their challenge openly. Yes, a split, for you have gone the whole hog with your splitting. Yes, a split, for we have exhausted all means of delay and of obtaining a Party decision (by a Third Congress). Yes, a split, for everywhere the disgusting squabbles with the disorganizers have only harmed the cause.”

Vladimir Lenin (1905). A letter to the Zurich group of Bolsheviks. [MIA] - ↑ “At a meeting of Bolsheviks, headed by Lenin, held in Geneva on November 29 (December 12), the question of founding a Bolshevik Party organ was finally decided. The meeting endorsed Lenin's suggestion for the name of the newspaper - Vperyod (Forward) - and the text of the announcement of its publication. The name Lenin had chosen for the paper expressed the Bolsheviks' determination to push ever forward in the work of consolidating the Party and of organizing the working-class movement, whereas the Mensheviks were trying to drag the Party back to the outlived stage of organizational disunity and the circle principle. The meeting set up the editorial board of the paper – Lenin, V. Vorovsky, M. Olminsky and A. Lunacharsky – and discussed the articles prepared for the first issue. As V. Karpinsky, a participant in the meeting, recalls, this free discussion and frank criticism, a striking manifestation of inner-Party democracy, deeply impressed the rank-and-file Party members.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; The campaign for the convocation of the Third Congress' (p. 108). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “The first issue of Vperyod came out in Geneva on December 22, 1904 (January 4, 1 905). The issue included several articles written by Lenin, among them "The Autocracy and the Proletariat" ( editorial), "Good Demonstrations of Proletarians and Poor Arguments of Certain Intellectuals" and "Time to Call a Halt!". Lenin stressed the fact that "the line of Vperyod is the line of the old 'Iskra'. In the name of the old Iskra, Vperyod resolutely combats the new Iskra". Under Lenin's guidance the newspaper Vperyod played an important part in the struggle to consolidate the Party and in the preparations for the Third Congress.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'For a proletarian party of a new type; The campaign for the convocation of the Third Congress' (p. 109). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “The year 1905 began with events that were destined to make history. On January 3, a strike broke out at the Putilov Works in St. Petersburg, involving 13,000 workers. The Putilov strike was supported by the workers of other St. Petersburg factories. On January 7, the strike became general.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'The first assault on the tsarist autocracy' (p. 111). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “The collective experience of all Party members, Lenin felt, was of vital importance to the proper solution of the questions of organization and tactics raised by the revolutionary movement. He proposed that all the Party committees, both Bolshevik and Menshevik, be invited to the Congress. But the Mensheviks refused to participate in the Third Congress. Instead, acting as a body entirely split away from the Party, they called a congress of their own, in Geneva.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'The first assault on the tsarist autocracy; The Third Party Congress' (p. 117). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “Therefore, the Third Congress of the R.S.D.L.P. holds that the task of organizing the proletariat for direct struggle against the autocracy by means of the armed uprising is one of the major and most urgent tasks of the Party at the present revolutionary moment.”

Central Comittee of the RSDLP (1905). The Third Congress of the R.S.D.L.P.: 'Resolution on the armed uprising'. [MIA] - ↑ “In June-July 1905 Lenin wrote the book Two Tactics of Social-Democracy in the Democratic Revolution. It was published in Geneva at the beginning of August. In Two Tactics Lenin set forth the theoretical considerations behind the Third Congress decisions, behind the Bolsheviks' strategic plan and tactical line in the revolution. [...] At the same time he subjected to devastating criticism the tactical line adopted by the Mensheviks at their Geneva conference, and pointed out the basic difference between the Bolshevik and the Menshevik tactics in the revolution.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'The first assault on the tsarist autocracy; Two tactics of social-democracy in the democratic revolution' (pp. 120-121). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “Lenin arrived in St. Petersburg on November 8 (21), 1905, and immediately launched vigorous revolutionary activity, directing the work of the Central and St. Petersburg Bolshevik committees, addressing meetings and conferences in St. Petersburg and in Moscow, conferring with Party functionaries, writing articles for the Bolshevik press. Under his leadership, the Bolsheviks carried on energetic preparations for an armed uprising.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'The first assault on the tsarist autocracy; In revolutionary Russia' (p. 127). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ “A most important place in the Revolution of 1905-07 is held by the December armed uprising in Moscow. An outstanding role in it was played by the Moscow Soviet and the district Soviets of Workers' Deputies led by the Bolsheviks. They consistently pursued a revolutionary policy and acted as the militant organs of the leadership of the uprising.

[...]

By 16 December the superiority of the government forces had become obvious. The Moscow Committee of Bolsheviks and the Executive Committee of the Moscow Soviet passed a decision to end the uprising in order to retreat in an organized fashion and preserve the revolutionary forces.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'The first assault on the tsarist autocracy; In revolutionary Russia' (pp. 130-131). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ Vladimir Lenin (1906). Lessons of the Moscow Uprising. [MIA]

- ↑ “One evening towards the end of February Lenin spoke on work in the countryside at a meeting of Party functionaries held in the home of a St. Petersburg barrister. Leaving the house after the meeting, Lenin noticed that he was being followed, and decided not to go home. Not without difficulty had he shaken off his pursuers and left for Finland.

[...]

Towards the end of the summer of 1906 Lenin settled down at Vasa, a country-house in Kuokkala occupied by the Bolshevik G. Leiteizen and his family. Situated in a secluded spot at the edge of a wood, Vasa was very convenient as a hiding-place. Lenin lived there, on and off, up to December 1907, making secret trips, to St. Petersburg.”

Pyotr Pospelov & Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1965). Lenin: a biography: 'The first assault on the tsarist autocracy; Victory at the Fifth Congress of the R.S.D.L.P.' (p. 136). Moscow: Progress Publishers, CC CPSU. [LG] - ↑ Stephen Gowans (2018). Patriots, Traitors and Empires: The Story of Korea’s Struggle for Freedom: 'The Empire of Japan' (p. 38). [PDF] Montreal: Baraka Books. ISBN 9781771861427 [LG]

- ↑ Vijay Prashad (2017). Red Star over the Third World: 'Red October' (pp. 28–29). [PDF] New Delhi: LeftWord Books.

- ↑ Vijay Prashad (2017). Red Star over the Third World: 'Eastern Graves' (pp. 16–17). [PDF] New Delhi: LeftWord Books.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Ludo Martens (1996). Another View of Stalin: 'The young Stalin forges his arms' (pp. 21–25). [PDF] Editions EPO. ISBN 9782872620814

- ↑ “The bourgeois and Menshevik press generally understand under the designation of “Testament” one of Comrade Lenin’s letters (which is so much altered as to be almost unrecognizable) in which he gives the party some organizational advice. The Thirteenth Party Congress devoted the greatest attention to this and to the other letters, and drew the appropriate conclusions. All talk with regard to a concealed or mutilated “Testament” is nothing but a despicable lie, directed against the real will of Comrade Lenin and against the interests of the party created by him.”

Leon Trotsky (1925-7-1). "Letter on Eastman’s Book" Marxist Internet Archive.

Notes[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Russian: Владимир Ильич Ульянов

- ↑ Russian: Симбирск

The city of Simbirsk was the administrative center of Simbirsk Governorate, which was one of the administrative divisions of the Russian Empire. The city is now known as Ulyanovsk, of the Ulyanovsk Region in the Russian Federation, in honor of Lenin. - ↑ Current calendar (Gregorian)

- ↑ The article is available on Marxists Internet Archive.

- ↑ Russian: Союз борьбы за освобождение рабочего класса, lit. Union of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class

- ↑ Russian: Рабочая Газета

- ↑ Russian: Искра (Spark)

- ↑ Russian: Заря (Dawn)

- ↑ Russian: Большевики, from большинство, 'majority'

- ↑ Russian: Меньшевики, from меньшинство, 'minority'

- ↑ Russian: Вперёд (Forward)