More languages

More actions

Itsraining (talk | contribs) m (Infobox: added some fields + use templates for birth and death dates) |

(intrawiki links) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

=== Brussels === | === Brussels === | ||

Upon arrival Engels secured an immigration permit to allow him to stay in [[Kingdom of Belgium|Belgium]] and lodgings nearby Marx's own before moving into a house next to Marx's in May 1845, nearby many of their other colleagues. They set to work immediately with Engels | Upon arrival Engels secured an immigration permit to allow him to stay in [[Kingdom of Belgium|Belgium]] and lodgings nearby Marx's own before moving into a house next to Marx's in May 1845, nearby many of their other colleagues. They set to work immediately, with Engels using Brussels a base through which to travel to the rest of Europe for his revolutionary and theoretical work. In the summer of 1845 they travel back to Manchester where Engels re-established his links to the socialist movement there and introduces Marx to them as well as holding talks with the [[League of the Just]] and the [[Fraternal Democrats]]. In Manchester Engels also reunited with Mary Burns who travelled with them back to Brussels at the end of their trip. Mary stayed with them until August 1846 and after a hard year financially for the pair she returned to England whilst Engels travelled to Paris.<ref>{{Citation|author=John Green|year=2008|title=Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels|title-url=https://annas-archive.org/md5/4a0fd9bca4001d2b831d132679299abc|chapter=Exile and the Communist Manifesto|section=|page=99-103|publisher=Artery Publications|isbn=978-0-9558228-0-3|lg=https://library.lol/main/4a0fd9bca4001d2b831d132679299abc}}</ref> | ||

The year in Brussels was used by Engels and Marx to write [[The German ideology|''The German ideology'']], a manuscript critiquing idealist philosophy and laying the groundwork for historical materialism, but they failed to publish it due to censorship laws. In early 1846 the [[Brussels Communist Correspondence Committee]] was set up by Marx, Engels and [[Philippe Gigot]] as a first attempt at an international and it is for this that Engels travelled to Paris in August. Between taking part in the carnal pleasures of the city, Engels did plenty of revolutionary work; forging links with the French workers' movements, and meeting with other revolutionaries such as [[Heinrich Heine]] whilst fighting against the [[Social democracy|social democratic]] deviations of [[Karl Grün]] and other similar counter-revolutionaries.<ref>{{Citation|author=John Green|year=2008|title=Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels|title-url=https://annas-archive.org/md5/4a0fd9bca4001d2b831d132679299abc|chapter=Exile and the Communist Manifesto|section=|page=103-107|publisher=Artery Publications|isbn=978-0-9558228-0-3|lg=https://library.lol/main/4a0fd9bca4001d2b831d132679299abc}}</ref> | The year in Brussels was used by Engels and Marx to write [[The German ideology|''The German ideology'']], a manuscript critiquing idealist philosophy and laying the groundwork for historical materialism, but they failed to publish it due to censorship laws. In early 1846 the [[Brussels Communist Correspondence Committee]] was set up by Marx, Engels and [[Philippe Gigot]] as a first attempt at an international and it is for this that Engels travelled to Paris in August. Between taking part in the carnal pleasures of the city, Engels did plenty of revolutionary work; forging links with the French workers' movements, and meeting with other revolutionaries such as [[Heinrich Heine]] whilst fighting against the [[Social democracy|social democratic]] deviations of [[Karl Grün]] and other similar counter-revolutionaries.<ref>{{Citation|author=John Green|year=2008|title=Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels|title-url=https://annas-archive.org/md5/4a0fd9bca4001d2b831d132679299abc|chapter=Exile and the Communist Manifesto|section=|page=103-107|publisher=Artery Publications|isbn=978-0-9558228-0-3|lg=https://library.lol/main/4a0fd9bca4001d2b831d132679299abc}}</ref> | ||

At the beginning of | At the beginning of 1847 the League of the Just ask Engels and Marx to join them and the pair agree on the condition that they can shape it into a more principled organisation and thus the [[League of Communists]] is born. With the absence of Marx in the first and second congresses Engels had to fight hard against the [[Utopian socialism|utopian socialists]] to achieve their goals but he managed it and their proposals were adopted. During this time Engels travelled back and forth between Brussels and Paris, helped by his fathers money who had begun funding him again the previous October after realising he still needed him, helping organise in both locations and became secretary of the [[Paris Regional Committee]]. At the end of October 1847 Engels began writing ''[[The principles of communism]]'' as a draft programme for the League's second congress, which once finished are presented and discussed with the League's Parisian cells before becoming the first draft for the Manifesto itself.<ref>{{Citation|author=John Green|year=2008|title=Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels|title-url=https://annas-archive.org/md5/4a0fd9bca4001d2b831d132679299abc|chapter=Exile and the Communist Manifesto|section=The Manifesto of the Communist Party|page=108-111|publisher=Artery Publications|isbn=978-0-9558228-0-3|lg=https://library.lol/main/4a0fd9bca4001d2b831d132679299abc}}</ref> | ||

== Later Life == | == Later Life == | ||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

* (1861) [[Library:The civil war in the United States|The civil war in the United States]] | * (1861) [[Library:The civil war in the United States|The civil war in the United States]] | ||

* (1872) [[Library:On authority|On authority]] | * (1872) [[Library:On authority|On authority]] | ||

* (1872) [[Library:The Housing Question|The Housing Question]] | |||

* (1876) [[Library:The part played by labour in the transition from ape to man|The part played by labour in the transition from ape to man]] | * (1876) [[Library:The part played by labour in the transition from ape to man|The part played by labour in the transition from ape to man]] | ||

* (1878) [[Library:Anti-Dühring|Anti-Dühring]] | * (1878) [[Library:Anti-Dühring|Anti-Dühring]] | ||

| Line 99: | Line 100: | ||

[[Category:German philosophers]] | [[Category:German philosophers]] | ||

[[Category:Political theorists]] | [[Category:Political theorists]] | ||

[[Category:Featured page]] | |||

Latest revision as of 17:38, 9 November 2024

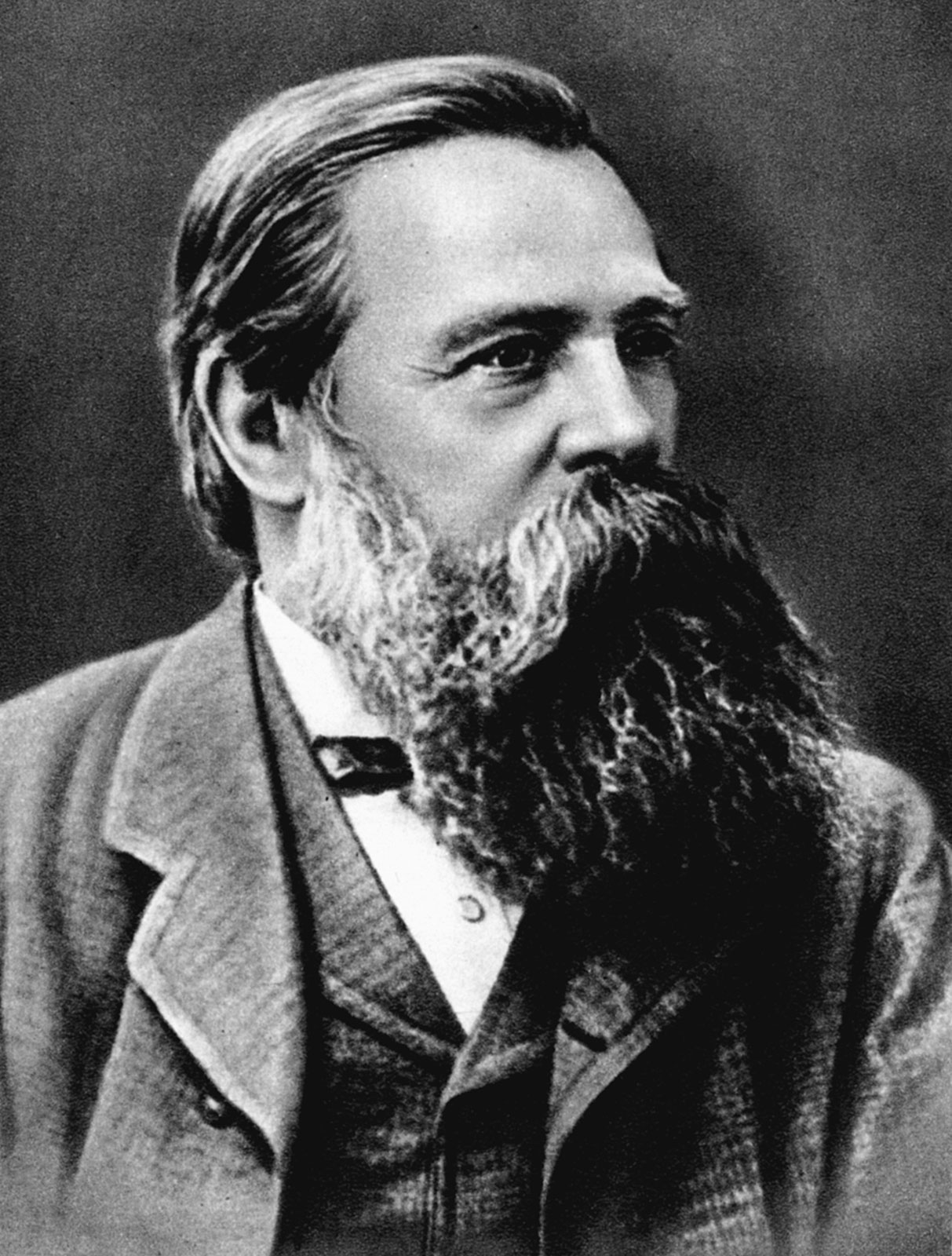

Friedrich Engels | |

|---|---|

Comrade Engels in 1879 | |

| Born | 28 November 1820 Barmen, Kingdom of Prussia, German Confederation |

| Died | 5 August 1895 (aged 74) London, England, Great Britain and Ireland |

| Nationality | German |

| Known for | Marxism |

| Field of study | Philosophy, science, political economy, history |

Friedrich Engels (28 November 1820 – 5 August 1895), sometimes anglicized as Frederick Engels, was a German philosopher, historian, political scientist and revolutionary socialist. Together with his friend and long time collaborator Karl Marx, he developed the materialist scientific explanation of history and economics, which later became known as Marxism.

Engels was Marx’s dearest friend and inseparable comrade in arms, co-developer of dialectical materialism and scientific socialism and co-author with Marx of the Communist Manifesto; one of the founders of the Communist League and the International Association of Workingmen or First International.

Early Life[edit | edit source]

Barmen[edit | edit source]

On 28 November 1820 Engels was born in the city of Barmen in the Kingdom of Prussia, a town of less than 40,000 located in the Rhineland. Of nine children (four brothers, four sisters) he was the eldest son of Elise von Haar and capitalist, Friedrich Engels Sr, owner of a string of cotton mills. His childhood was privileged and his parents raised him in a supportive, loving but also conservative and devoutly Pietist Protestant environment. The only element of his parents values Engels inherited was that of philanthropy, he was the only one of his brothers to not willingly join the family business and adopt their narrow conservative viewpoint.[1]

In 1828 Engels begun school and attended the elementary school in Barmen until the age of 14, a pious school at which his father sat on the board of governors. In 1834 he was transferred to the evangelical Gymnasium (grammar school) in the neighbouring town of Elberfeld so he could be prepared for his future role of taking on the family firm. The school was one of the best in Prussia and whilst attending Engels was provided lodgings by the provisional headmaster Hantschke. In school Engels began to diverge away from his father's ideology and he was particularly interested in the sciences and works of the philosophers, whilst being very proficient in languages.[2]

Engels planned to complete the Abitur and continue on to university to read political economy or something similar, but to his dismay just nine months before his final exams his father decided to pull him out of school so he could start business training. In September 1837 Engels is placed as a junior clerk in his father's business where he shadows his father and enjoys accompanying him on business trips to London, Amsterdam and Rotterdam. Engels Sr had grandiose plans for the family business of Ermen & Engels and wanted to groom Engels for leadership and have him learn not only general business skills, but study European textile production techniques and marketing. Engels' personal feelings of disinterest with business were disregarded by his father and he was forced to hide his fascination with poetry and his interest in the work of Ferdinand Freiligrath from him.[3]

Bremen[edit | edit source]

In July 1838 Engels is sent to Bremen in Northern Germany to complete an apprenticeship at a trading house owned by Consul Heinrich Leupold. He finds a lot of the work boring and entertains himself by sending humours letters to his friends and siblings and by engaging in literary pursuits. In Bremen Engels is exposed to the poverty of the city and his views continue to slowly develop with him displaying strong republican sentiments, hatred of the monarchy and a desire to break free of his religious upbringing. In 1839 he publishes his first journalistic work under a pseudonym in the Telegraph für Deutschland, where he critically reviews a work by philosopher Karl Gutzkow, which allowed him to continue writing articles for them.[4]

Engels was already very aware of existing social relations and would write an article about the uncertain position of the German peasantry in the Morgenblatt für gebildete Leser. In 1839 Engels was already asking for revolutionary action and for the people to be involved in state power as well as doing away with censorship, special rights for the aristocracy and for there to be full rights for Jews. At the age of 20 Engels engaged fully with cultural pursuits and practiced sports, studied music with a particular fondness for Beethoven as well as learned a multitude of foreign languages, including English, French, Dutch, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese,[5] and Russian.[6]

As mandatory military service approached although Engels could have dodged service through his father's influence Engels was adamant he was going to serve like everyone else and reported punctually to the Barmen conscription office where he was placed in the artillery. Whilst waiting to be called up Engels continued accompanying his father on foreign business trips in between working on his apprenticeship. Engels has plenty of time for writing and reading alongside his official work and in this time he publishes his first book: The Life, Character and Philosophy of Horace — a Dialogue. At the end of March 1841 Engels finishes his apprenticeship and left Bremen but not before winning two duels in four weeks.[7]

Military service[edit | edit source]

At the end of September 1841 Engels travelled to Berlin to report for his military service on 1 October where he was quartered in the barracks on the Kupfergraben, only a short walk from Berlin’s Friedrich Wilhelm’s University (today the Humboldt University) where Engels would spend much of his time. Engels disliked Berlin and although at first he resisted using the privileges allowed to him he eventually relented and moved into private accommodations using his father's money and took advantage of leave to continue his studies. Engels soon grew tired of the ceaseless marching around the Schlossplatz (ironically later renamed by the German Democratic Republic to ‘Marx-Engels Platz’), so much so that one of his highlights of the year was adopting a spaniel named Namenloser (Nameless) who he taught to growl when he said "there’s an aristocrat!"[8]

Despite his dislike for life in the military he accepted it diligently and took the opportunity to pick up important military knowledge that he used to great effect in later life. However what he learned the most from was the university, attending classes whenever he could get away despite not being a registered student and he diligently acquired notes from other students for lectures he could not attend. Engels was particularly excited by the ideas of Hegel for his theories on dialectics, but Engels fell into the category of Young Hegelians who rejected the Hegels' idealism and belief in God, a position influenced by Engels' reading of materialist philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach.[9]

Engels' understanding of the philosophy was very advanced for someone of his age and his anonymous brochures rebutting the idealist Schelling's criticism of Hegels won him much praise. His radical tendencies soon outstripped those of the Young Hegelians and he began writing for the Rheinische Zeitung which was increasingly taking a socialist position over time. In October 1842 Engels completed his military service and returned to Barmen but on his way he travelled to Cologne, the headquarters of the Rheinische Zeitung. There Engels meets Rave, Hess and Rutenberg, editors of the paper. Hess in particular is impressed by Engels and thanks partly to his influence Engels embraces communism. Back in Barmen his father has heard of Engels' radicalism and decided to send his son to Manchester, England, to continue his business training. Engels departed for Manchester in November 1842 but on the way there he stopped in Cologne and offers to become the paper's English correspondent. Here is when Engels first meets Marx; the meeting was cold and Marx was unimpressed by Engels, wrongly believing him to still be a Young Hegelian.[10]

Young Socialist[edit | edit source]

Manchester[edit | edit source]

Engels arrived in Manchester in December 1842 at the height of the chartist movement and upon observing the conditions of the proletariat found that his preconceptions about England to have been incorrect leading him further along the path of anti-capitalism. As a general assistant learning about the English industrial and economic system Engels got to interact with the proletariat more than he ever has previously and was excited to learn about them and the class struggle; he was impatient for the revolution to happen as soon as possible. Engels had to overcome his youthful ignorance on many matters and to accomplish this he threw himself into learning fully, influenced by poets such as Shelley, whilst trying to avoid his work as much as possible.[11]

Engels first personal contacts with the Chartist movement were through George Harney and James Leach in 1843 who taught him much about England and its class struggle and he in return taught them about continental socialism. Engels' interactions with the chartist movement influenced many on the left as well as those that followed Robert Owen and helped them see the larger socialist movement outside of Britain by writing articles in the New Moral World and also in the Northern Star. Engels was disappointed that so many of the so called socialist movements were marred by idealism and religiosity, although he did manage to learn from the ideas of Owen and Proudhon in spite of their idealism.[12]

Over his time in Manchester Engels moved towards the assertion that scientific communism is the solution and expanded on his knowledge of the proletariat's living and working conditions using the works of economists Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Jean-Baptiste Say, and many more. To the disappointment of Engels Sr, Engels demonstrated little interest in learning how to make money and rather learned about the socio-political aspects of the factory system. To conduct his investigation of the conditions of the proletariat Engels relied upon the help of Mary Burns, an intelligent Irish woman with whom he struck up a relationship with for the entirety of her life but never married because of their opposition to the institution of marriage.[13]

In 1843 Engels wrote the essay Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy which represented Engels' first attempt at basing socialism on political economy, demonstrating that Engels was already fluent enough in economics to critique the work of Smith, Ricardo and Malthus. This essay published in 1844 in Marx's new publication, the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, would trigger the start of correspondence between Marx and Engels that would later blossom into friendship. In August 1844 at the end of his training period Engels left Britain in possession of a wider range of ideas than when he arrived and with more clarity of the future, but on the way back to Barmen Engels decided to stop in Paris where Marx was presently staying.[14]

Paris[edit | edit source]

In the ten days Engels was able to stay in Paris he formed a close relationship with Marx which set the groundwork for a lifelong collaboration and friendship. In the days locked in serious debate they found they were in agreement on pretty much everything having formed the same conclusions through different methods, a contrast seen when Engels undertook debate with others whilst in Paris such as Mikhail Bakunin. The meeting of Engels and Marx in Paris also happened to coincide with the arrival of an article by Bruno Bauer criticizing their essays in Marx's publication. The pair immediately set to work on writing their response and the result was The holy family which criticized Bauer and his Hegelian idealism.[15]

Engels after writing the first draft of the response had to leave Paris to return to Barmen and was surprised to find Marx had expanded his pamphlet into a full book when he received his own copy. After a short stop in Cologne for three days to brief members of their circle on new developments Engels arrived home where after sisters wedding he was forced to resume work in the family business. From mid-November 1844, in between work, a short love affair, revolutionary pursuits and reading the works of Stirner among others, Engels worked on compiling his research into a manuscript until mid-March when he completed The conditions of the working class in England. Following the book's completion, with tensions high at home and the Prussian government clamping down on communist agitation, Engels decided to take what money he had and go into voluntary exile joining Marx in Brussels.[16]

Brussels[edit | edit source]

Upon arrival Engels secured an immigration permit to allow him to stay in Belgium and lodgings nearby Marx's own before moving into a house next to Marx's in May 1845, nearby many of their other colleagues. They set to work immediately, with Engels using Brussels a base through which to travel to the rest of Europe for his revolutionary and theoretical work. In the summer of 1845 they travel back to Manchester where Engels re-established his links to the socialist movement there and introduces Marx to them as well as holding talks with the League of the Just and the Fraternal Democrats. In Manchester Engels also reunited with Mary Burns who travelled with them back to Brussels at the end of their trip. Mary stayed with them until August 1846 and after a hard year financially for the pair she returned to England whilst Engels travelled to Paris.[17]

The year in Brussels was used by Engels and Marx to write The German ideology, a manuscript critiquing idealist philosophy and laying the groundwork for historical materialism, but they failed to publish it due to censorship laws. In early 1846 the Brussels Communist Correspondence Committee was set up by Marx, Engels and Philippe Gigot as a first attempt at an international and it is for this that Engels travelled to Paris in August. Between taking part in the carnal pleasures of the city, Engels did plenty of revolutionary work; forging links with the French workers' movements, and meeting with other revolutionaries such as Heinrich Heine whilst fighting against the social democratic deviations of Karl Grün and other similar counter-revolutionaries.[18]

At the beginning of 1847 the League of the Just ask Engels and Marx to join them and the pair agree on the condition that they can shape it into a more principled organisation and thus the League of Communists is born. With the absence of Marx in the first and second congresses Engels had to fight hard against the utopian socialists to achieve their goals but he managed it and their proposals were adopted. During this time Engels travelled back and forth between Brussels and Paris, helped by his fathers money who had begun funding him again the previous October after realising he still needed him, helping organise in both locations and became secretary of the Paris Regional Committee. At the end of October 1847 Engels began writing The principles of communism as a draft programme for the League's second congress, which once finished are presented and discussed with the League's Parisian cells before becoming the first draft for the Manifesto itself.[19]

Later Life[edit | edit source]

Marx and Engels returned to Germany to fight in the revolutions of 1848. He fled to London through Switzerland after the revolution was defeated. He moved to Manchester, where he lived until 1870. After Marx's death in 1883, he prepared and published the second and third volumes of Capital. He planned to release a fourth volume but died in 1895 before it was finished.[6]

Library works[edit | edit source]

- (1844) The holy family

- (1845) The conditions of the working class in England

- (1846) The German ideology

- (1847) The principles of communism

- (1848) Manifesto of the Communist Party

- (1850) The peasant war in Germany

- (1861) The civil war in the United States

- (1872) On authority

- (1872) The Housing Question

- (1876) The part played by labour in the transition from ape to man

- (1878) Anti-Dühring

- (1880) Socialism: utopian and scientific

- (1884) The origin of the family, private property and the state

- (1886) Ludwig Feuerbach and the end of classical German philosophy

- (1892) The Mark

- (1894) A contribution to the history of primitive Christianity

- (1896) Revolution and counter-revolution in Germany (Posthumous)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'A wild seed' (pp. 14-18). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'A wild seed; Early boyhood' (pp. 20-22). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'A wild seed; Early boyhood' (pp. 22-24). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'A wild seed; Flying the nest' (pp. 25-27). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'A wild seed; Flying the nest' (pp. 28-30). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Vladimir Lenin (1895). Frederick Engels. [MIA]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'A wild seed; Flying the nest' (pp. 31-34). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'Soldiering for the King' (pp. 35-37). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'Soldiering for the King' (pp. 37-43). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'Soldiering for the King' (pp. 42-47). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'Love in the satanic mills; The workshop of the world' (pp. 53-61). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'Love in the satanic mills; Workshop of the world' (pp. 61-68). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'Love in the satanic mills; The condition of the working class' (pp. 69-71). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'Love in the satanic mills; The condition of the working class' (pp. 80-83). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'Love in the satanic mills; The condition of the working class' (pp. 83-85). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'Love in the satanic mills; Back in Barmen' (pp. 85-96). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'Exile and the Communist Manifesto' (pp. 99-103). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'Exile and the Communist Manifesto' (pp. 103-107). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]

- ↑ John Green (2008). Engels: A Revolutionary Life: A Biography of Friedrich Engels: 'Exile and the Communist Manifesto; The Manifesto of the Communist Party' (pp. 108-111). Artery Publications. ISBN 978-0-9558228-0-3 [LG]