Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela: Difference between revisions

More languages

More actions

Tag: Visual edit |

RedCustodian (talk | contribs) m (Reverted edit by VikDiurnal (talk) to last revision by General-KJ) Tag: Rollback |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

|capital=Caracas|largest_city=Caracas| image_map = Venezuela Map.svg | |capital=Caracas|largest_city=Caracas| image_map = Venezuela Map.svg | ||

| image_map_size = 260px | | image_map_size = 260px | ||

|map_caption=Map of Venezuela according to the 2023 referendum| official_languages = Spanish | |map_caption=Map of Venezuela according to the 2023 referendum. Light green territories are not recognized by the UN.| official_languages = Spanish | ||

| recognized_national_languages = 26 indigenous languages | | recognized_national_languages = 26 indigenous languages | ||

| area_km2 = 916,445 | | area_km2 = 916,445 | ||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

=== Early republic === | === Early republic === | ||

In 1815, Britain recognized the 1777 borders of Venezuela. In 1822, under the orders of [[Simón Bolívar]], Ambassador [[José Rafael Revenga]] criticized British intrusions west of the Esequibo. After [[Gran Colombia]] broke apart, the Michelena-Pombo Treaty of 1833 divided the Guajira Peninsula roughly in half between Colombia and Venezuela. The Venezuelan parliament rejected the treaty and continued to dispute the region until 1883 | In 1815, Britain recognized the 1777 borders of Venezuela. In 1822, under the orders of [[Simón Bolívar]], Ambassador [[José Rafael Revenga]] criticized British intrusions west of the Esequibo. After [[Gran Colombia]] broke apart, the Michelena-Pombo Treaty of 1833 divided the Guajira Peninsula roughly in half between Colombia and Venezuela. The Venezuelan parliament rejected the treaty and continued to dispute the region until 1883.<ref name=":2" /> | ||

In 1840, the Royal Geographic Society of London sent [[Robert Schomburgk]], a [[Holy Roman Empire (800–1806)|German]] geographer, to map the border between Venezuela and British Guyana. His map claimed the sparsely populated Guayana Esequiba and Tigri regions as part of Guyana.<ref name=":2 | In 1840, the Royal Geographic Society of London sent [[Robert Schomburgk]], a [[Holy Roman Empire (800–1806)|German]] geographer, to map the border between Venezuela and British Guyana. His map claimed the sparsely populated Guayana Esequiba and Tigri regions as part of Guyana. In 1841, [[Alejo Fortique]], the Venezuelan ambassador to the UK, argued the Esequibo issue and made the British agree to future negotiations on the border. After he died in 1845, Venezuela agreed to postpone border negotiations.<ref name=":3">{{Web citation|author=Saheli Chowdhuri|newspaper=[[Orinoco Tribune]]|title=Essequibo and Other Border Issues: Venezuela’s Territorial Losses to Imperialist Powers Through the Centuries (Part 2)|date=2023-12-03|url=https://orinocotribune.com/essequibo-and-other-border-issues-venezuelas-territorial-losses-to-imperialist-powers-through-the-centuries-part-2/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231204033538/https://orinocotribune.com/essequibo-and-other-border-issues-venezuelas-territorial-losses-to-imperialist-powers-through-the-centuries-part-2/|archive-date=2023-12-04}}</ref> | ||

General [[Ezequiel Zamora]] led the [[peasantry]] in the [[Federal War]] (1859–1863). He fought against the [[ruling class]] while trying to redistribute land and wealth.<ref name=":1">{{Web citation|date=2023-02-28|title=The Strategic Revolutionary Thought and Legacy of Hugo Chávez Ten Years After His Death|url=https://thetricontinental.org/dossier-61-chavez/|newspaper=[[Tricontinental]]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230429215204/https://thetricontinental.org/dossier-61-chavez/|archive-date=2023-04-29}}</ref> | General [[Ezequiel Zamora]] led the [[peasantry]] in the [[Federal War]] (1859–1863). He fought against the [[ruling class]] while trying to redistribute land and wealth.<ref name=":1">{{Web citation|date=2023-02-28|title=The Strategic Revolutionary Thought and Legacy of Hugo Chávez Ten Years After His Death|url=https://thetricontinental.org/dossier-61-chavez/|newspaper=[[Tricontinental]]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230429215204/https://thetricontinental.org/dossier-61-chavez/|archive-date=2023-04-29}}</ref> | ||

=== United States of Venezuela (1864–1953) === | === United States of Venezuela (1864–1953) === | ||

[[File:Guyana Disputed Areas.svg.png|thumb|253x253px|Venezuela claims the Guayana Esequiba region, which Guyana currently controls.]] | After the Federal War, Juan Cristósomo Falcón became President and appointed [[Antonio Guzmán Blanco]] as representative to Britain. Britain rejected Guzmán Blanco's attempts to solve the border dispute in the 1870s and 1880s. In 1883, [[Kingdom of Spain (1874–1931)|Spain]] also ended the Guajira dispute in favor of Colombia, and President Guzmán Blanco recognized the result. Venezuela ended relations with the UK in 1887 and mistakenly asked for the USA's help against Britain.[[File:Guyana Disputed Areas.svg.png|thumb|253x253px|Venezuela claims the Guayana Esequiba region, which Guyana currently controls.]] | ||

In 1895, | In 1895, the United States asserted the [[Monroe Doctrine]], which considers the Americas to be territory for colonization by the USA rather than colonization by [[Europe]]. The UK initially refused to negotiate until the USA threatened war. In 1897, after the UK refused to negotiate with Venezuela, which it considered uncivilized, the USA decided to negotiate on Venezuela's behalf without taking its interests into account. The UK and USA created a tribunal of five people: two from the UK and three from the USA. The last member, [[Frederick Fyodor Martens]], was a [[Russian Empire (1721–1917)|Russian]] diplomat who wanted Russia and Britain to cooperate in invading Central Asia. In 1899, the tribunal created the Paris Arbitration Award, which surrendered Guayana Esequibo the British.<ref name=":3" /> The affair was an early instance of the Monroe Doctrine being invoked and the U.S. asserting itself as an imperial power.<ref>[https://history.state.gov/milestones/1866-1898/venezuela “Milestones: 1866–1898 - Office of the Historian.”] 2023. State.gov. 2023.</ref><ref name=":0">Wilkins, Brett. [https://www.telesurenglish.net/opinion/The-History--and-Hypocrisy--of-US-Meddling-in-Venezuela--20190128-0016.html “The History - and Hypocrisy - of US Meddling in Venezuela.”] Telesurenglish.net. teleSUR. 2018. [https://web.archive.org/web/20230307033238/https://www.telesurenglish.net/opinion/The-History--and-Hypocrisy--of-US-Meddling-in-Venezuela--20190128-0016.html Archived] 2023-03-07.</ref> | ||

From 1902 to 1903, Venezuela was blockaded by [[Europe|European]] navies.<ref>{{News citation|title=US Imperialism in Nicaragua and the Making of Sandino|date=2020-02-21|url=https://www.telesurenglish.net/analysis/sandino-us-imperialism-making-20200219-0029.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210305215145/https://www.telesurenglish.net/analysis/sandino-us-imperialism-making-20200219-0029.html|archive-date=2021-03-05|retrieved=2022-06-25}}</ref> | From 1902 to 1903, Venezuela was blockaded by [[Europe|European]] navies.<ref>{{News citation|title=US Imperialism in Nicaragua and the Making of Sandino|date=2020-02-21|url=https://www.telesurenglish.net/analysis/sandino-us-imperialism-making-20200219-0029.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210305215145/https://www.telesurenglish.net/analysis/sandino-us-imperialism-making-20200219-0029.html|archive-date=2021-03-05|retrieved=2022-06-25}}</ref> | ||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

In December 1936, the oil [[Proletariat|workers]] of Maracaibo went on [[Strike action|strike]].<ref name=":122">{{Citation|author=[[Vijay Prashad]]|year=2008|title=The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World|chapter=Caracas|page=|pdf=https://cloudflare-ipfs.com/ipfs/bafykbzaceascnzh26r5d6uitjjs2z7rflhaxlt7rboz5whzdf76qg6xxvecqq?filename=%28A%20New%20Press%20People%27s%20history%29%20Vijay%20Prashad%20-%20The%20darker%20nations_%20a%20people%27s%20history%20of%20the%20third%20world-The%20New%20Press%20%282008%29.pdf|publisher=The New Press|isbn=9781595583420|lg=https://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=9B40B96E830128A7FE0E0E887C06829F}}</ref><sup>:176</sup> | In December 1936, the oil [[Proletariat|workers]] of Maracaibo went on [[Strike action|strike]].<ref name=":122">{{Citation|author=[[Vijay Prashad]]|year=2008|title=The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World|chapter=Caracas|page=|pdf=https://cloudflare-ipfs.com/ipfs/bafykbzaceascnzh26r5d6uitjjs2z7rflhaxlt7rboz5whzdf76qg6xxvecqq?filename=%28A%20New%20Press%20People%27s%20history%29%20Vijay%20Prashad%20-%20The%20darker%20nations_%20a%20people%27s%20history%20of%20the%20third%20world-The%20New%20Press%20%282008%29.pdf|publisher=The New Press|isbn=9781595583420|lg=https://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=9B40B96E830128A7FE0E0E887C06829F}}</ref><sup>:176</sup> | ||

In 1949, the Statesian Judge [[Otto Schoenrich]] published the [[Mallet-Prevost Memorandum]]. [[Severo Mallet-Prevost]] had been one of the Statesian lawyers at the 1899 Paris tribunal along with former [[President of the United States|U.S. president]] [[Benjamin Harrison]] and others. The memorandum described the tribunal in detail and said that the British had forced the U.S. jurors to accept an unequal treaty towards Venezuela.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

=== Fourth Republic (1953–1999) === | === Fourth Republic (1953–1999) === | ||

Oil production increased after [[Mexican United States|Mexico]] nationalized its oil in 1938, doubling in the 1950s. The dictator [[Marcos Pérez Jiménez]], who ruled from 1952 to 1958, used oil revenues to fund construction projects that did not help the workers. In 1958, a new progressive government led by the [[Democratic Action (Venezuela)|Democratic Action]] party planned to nationalize the oil industry.<ref name=":122" /><sup>:176–9</sup> [[Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonso|Juan Pérez]] helped establish [[Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries|OPEC]] in 1960.<ref name=":122" /><sup>:184</sup> | Oil production increased after [[Mexican United States|Mexico]] nationalized its oil in 1938, doubling in the 1950s. The dictator [[Marcos Pérez Jiménez]], who ruled from 1952 to 1958, used oil revenues to fund construction projects that did not help the workers. In 1958, a new progressive government led by the [[Democratic Action (Venezuela)|Democratic Action]] party planned to nationalize the oil industry.<ref name=":122" /><sup>:176–9</sup> [[Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonso|Juan Pérez]] helped establish [[Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries|OPEC]] in 1960.<ref name=":122" /><sup>:184</sup> | ||

When Guyana became independent from the British in 1966, Venezuela agreed to temporarily leave the Esequibo region under Guyana's control until they could reach a permanent solution. However, Venezuela did not recognize Guyananese authority over the disputed region. In 1970, with the Port of Spain Protocol, Prime Minister [[Eric Williams]] of Trinidad and Tobago made an agreement that Guyana and Venezuela would maintain bilateral ties and that Venezuela would not claim the Esequibo until 1982.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

[[Carlos Andrés Pérez]] ruled Venezuela from 1974 to 1979 and again from 1989 to 1993. He implemented the [[Neoliberalism|neoliberal]] Great Turnaround in 1989, causing [[Caracazo|mass protests]]. His successor, [[Rafael Caldera]], continued neoliberal rule and allowed foreign [[Imperialism|imperialists]] to own the economy. In 1992, [[Hugo Chávez]] and the [[MBR-200]] attempted to overthrow the neoliberal government and start a revolution.<ref name=":1" /> | [[Carlos Andrés Pérez]] ruled Venezuela from 1974 to 1979 and again from 1989 to 1993. He implemented the [[Neoliberalism|neoliberal]] Great Turnaround in 1989, causing [[Caracazo|mass protests]]. His successor, [[Rafael Caldera]], continued neoliberal rule and allowed foreign [[Imperialism|imperialists]] to own the economy. In 1992, [[Hugo Chávez]] and the [[MBR-200]] attempted to overthrow the neoliberal government and start a revolution.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

| Line 85: | Line 89: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Countries]] | |||

[[Category:Latin American countries]] | |||

[[Category:Global south]] | |||

[[Category:Anti-imperialist states]] | [[Category:Anti-imperialist states]] | ||

[[Category:Countries sanctioned by the US]] | [[Category:Countries sanctioned by the US]] | ||

[[Category:Targets of regime change operations]] | [[Category:Targets of regime change operations]] | ||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Venezuela}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Venezuela}} | ||

Latest revision as of 20:38, 3 December 2024

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela,[1] is a country on the northern coast of South America, sharing borders on the west with Colombia, Brazil to the south, Trinidad and Tobago to the northeast, and to the east with Guyana. It consists of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea.

In 1960, Venezuela produced 30% of the world's oil.[2]:184 Venezuela has been the target of hostility from the US imperialists due to its significant reserves of oil, as well as its recent trend of electing left-leaning progressive governments which prioritize social programs and the implementation of what some observers describe as Socialism of the 21st century.[3]

Under the anti-imperialist government of Hugo Chávez, unemployment decreased by almost half, GDP per capita more than doubled, infant mortality decreased, and extreme poverty dropped from 23.4% to 8.5%.[4]

History[edit | edit source]

Spanish colonialism[edit | edit source]

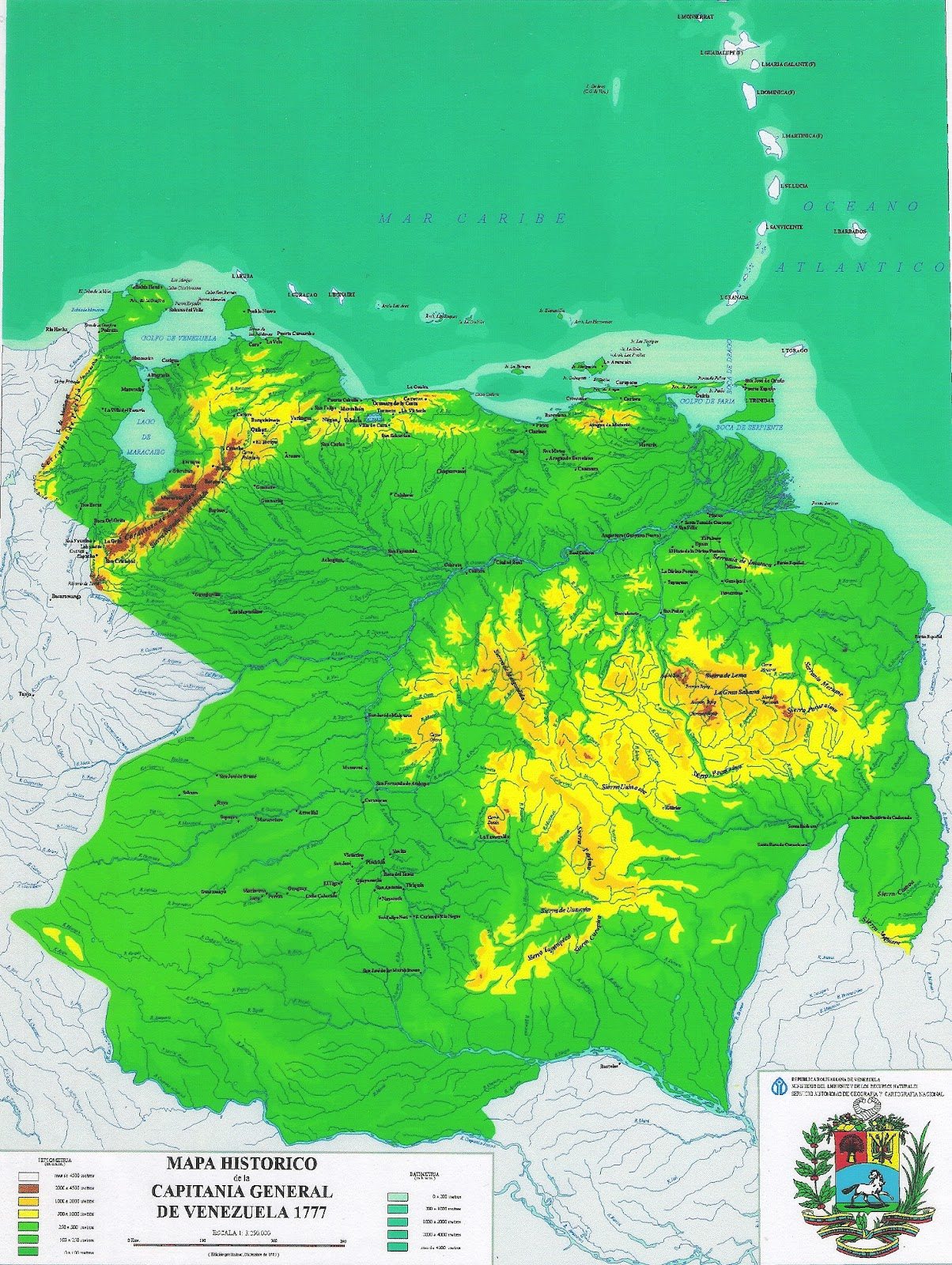

In 1777, a treaty between the Spanish and the Dutch defined the Esequibo River as the eastern border of the Captaincy General of Venezuela.

After losing control of its Thirteen Colonies in North America in 1776, the British Empire sought to take over parts of South America. In the early 19th century, it annexed the Guayana Esequiba region from Spanish-occupied Venezuela and the Tigri region from Dutch-occupied Suriname. Around the same time, Venezuela became independent from the Spanish.

In 1797, the British seized the island of Trinidad from Venezuela. The Spanish colonizers recognized it as British territory five years later with the Treaty of Amiens.[5]

Early republic[edit | edit source]

In 1815, Britain recognized the 1777 borders of Venezuela. In 1822, under the orders of Simón Bolívar, Ambassador José Rafael Revenga criticized British intrusions west of the Esequibo. After Gran Colombia broke apart, the Michelena-Pombo Treaty of 1833 divided the Guajira Peninsula roughly in half between Colombia and Venezuela. The Venezuelan parliament rejected the treaty and continued to dispute the region until 1883.[5]

In 1840, the Royal Geographic Society of London sent Robert Schomburgk, a German geographer, to map the border between Venezuela and British Guyana. His map claimed the sparsely populated Guayana Esequiba and Tigri regions as part of Guyana. In 1841, Alejo Fortique, the Venezuelan ambassador to the UK, argued the Esequibo issue and made the British agree to future negotiations on the border. After he died in 1845, Venezuela agreed to postpone border negotiations.[6]

General Ezequiel Zamora led the peasantry in the Federal War (1859–1863). He fought against the ruling class while trying to redistribute land and wealth.[7]

United States of Venezuela (1864–1953)[edit | edit source]

After the Federal War, Juan Cristósomo Falcón became President and appointed Antonio Guzmán Blanco as representative to Britain. Britain rejected Guzmán Blanco's attempts to solve the border dispute in the 1870s and 1880s. In 1883, Spain also ended the Guajira dispute in favor of Colombia, and President Guzmán Blanco recognized the result. Venezuela ended relations with the UK in 1887 and mistakenly asked for the USA's help against Britain.

In 1895, the United States asserted the Monroe Doctrine, which considers the Americas to be territory for colonization by the USA rather than colonization by Europe. The UK initially refused to negotiate until the USA threatened war. In 1897, after the UK refused to negotiate with Venezuela, which it considered uncivilized, the USA decided to negotiate on Venezuela's behalf without taking its interests into account. The UK and USA created a tribunal of five people: two from the UK and three from the USA. The last member, Frederick Fyodor Martens, was a Russian diplomat who wanted Russia and Britain to cooperate in invading Central Asia. In 1899, the tribunal created the Paris Arbitration Award, which surrendered Guayana Esequibo the British.[6] The affair was an early instance of the Monroe Doctrine being invoked and the U.S. asserting itself as an imperial power.[8][9]

From 1902 to 1903, Venezuela was blockaded by European navies.[10]

During the Dutch-Venezuelan crisis of 1908, the U.S. Navy helped Venezuelan Vice President Juan Vicente Gomez seize power in a coup. Gomez endeared himself to Washington and Wall Street by granting highly lucrative concessions to foreign oil companies including Standard Oil (ExxonMobil today) and Royal Dutch Shell.[9]

In December 1936, the oil workers of Maracaibo went on strike.[2]:176

In 1949, the Statesian Judge Otto Schoenrich published the Mallet-Prevost Memorandum. Severo Mallet-Prevost had been one of the Statesian lawyers at the 1899 Paris tribunal along with former U.S. president Benjamin Harrison and others. The memorandum described the tribunal in detail and said that the British had forced the U.S. jurors to accept an unequal treaty towards Venezuela.[6]

Fourth Republic (1953–1999)[edit | edit source]

Oil production increased after Mexico nationalized its oil in 1938, doubling in the 1950s. The dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez, who ruled from 1952 to 1958, used oil revenues to fund construction projects that did not help the workers. In 1958, a new progressive government led by the Democratic Action party planned to nationalize the oil industry.[2]:176–9 Juan Pérez helped establish OPEC in 1960.[2]:184

When Guyana became independent from the British in 1966, Venezuela agreed to temporarily leave the Esequibo region under Guyana's control until they could reach a permanent solution. However, Venezuela did not recognize Guyananese authority over the disputed region. In 1970, with the Port of Spain Protocol, Prime Minister Eric Williams of Trinidad and Tobago made an agreement that Guyana and Venezuela would maintain bilateral ties and that Venezuela would not claim the Esequibo until 1982.[6]

Carlos Andrés Pérez ruled Venezuela from 1974 to 1979 and again from 1989 to 1993. He implemented the neoliberal Great Turnaround in 1989, causing mass protests. His successor, Rafael Caldera, continued neoliberal rule and allowed foreign imperialists to own the economy. In 1992, Hugo Chávez and the MBR-200 attempted to overthrow the neoliberal government and start a revolution.[7]

Bolivarian government (1999–present)[edit | edit source]

Chávez presidency[edit | edit source]

The Bolivarian Revolution refers to a left-wing populist social movement and political process in Venezuela led by Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez who founded the Fifth Republic Movement and later the United Socialist Party of Venezuela. The "Bolivarian Revolution" is named after Simón Bolívar, an early 19th-century Venezuelan and Latin American revolutionary leader. According to Chávez and other supporters, the "Bolivarian Revolution" seeks to build a mass movement to implement Bolivarianism—popular democracy, economic independence, equitable distribution of revenues, and an end to political corruption—in Venezuela. They interpret Bolívar's ideas from a populist perspective, using socialist rhetoric.[11]

In 2004, Venezuela began the National System of Missions to address poverty, illiteracy, and health and housing problems. It also formed the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America with Cuba.[7] The Venezuelan and Cuban governments also teamed up for Operation Miracle, which provided treatment for people with eye problems in the Global South. The Great Housing Mission Venezuela has constructed over 4.2 million homes for poor and working class Venezuelans, with a goal of 5 million by 2025.[12] In 2006, construction began on a planned socialist community, Ciudad Caribia, which was the brainchild of Chávez.

On March 5, 2013, Chávez died after 14 years in office. His vice president Nicolás Maduro took over the office of the presidency.

Maduro presidency[edit | edit source]

The US maintains a blockade against Venezuela to try to strangle their independent economy. In August of 2021, Peru announced it would no longer participate in the blockade.[13] The blockade against Venezuela even negatively affects US businesses[14] and has caused 40,000 deaths due to lack of food and medicine.[15] Venezuelan capitalists have burned food[16] and buried it underground.[17] Despite this, Venezuela's malnutrition rate has decreased from 13.2% in 2001 to 8.2% in 2017.[18]

In 2021, president Maduro spoke to the UN General Assembly saying that 'we must build a "new world without imperialism"'[19]

Despite their elections being declared democratic by the US-based Carter Center[20], and not having the death penalty[21][22], the US media insists that Venezuela is a dictatorship with no regard for human rights, thus trying to lay the groundwork for "humanitarian interventions"[23]

Despite attempts at economic isolation, the US was forced to re-engage the Venezuelan economy for its oil.[24]

On March 17, 2022, President Maduro announced a new social media app called Ven App which will be used as a means of direct communication with the government, in an effort to help the government reach citizens with better services. It has been inspired by Russia's VK and China's WeChat.[25]

Imperialist aggression[edit | edit source]

US coup attempts[edit | edit source]

Chavismo has attracted repeated attacks from the US imperialists to the north, including coup attempts in 2002, 2019, and 2020,[26] among others.[27][28]

In his 2020 memoir The Room Where It Happened, John Bolton, former National Security Advisor under U.S. President Donald Trump, wrote regarding Venezuela:

Shortly after the drone attack [on Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro on August 4, 2018][29], during an unrelated meeting on August 15, Venezuela came up, and Trump said to me emphatically, “Get it done," meaning get rid of the Maduro regime. “This is the fifth time I've asked for it,” he continued. [...] Trump insisted he wanted military options for Venezuela and then keep it because “it's really part of the United States.”[30]

Sanctions[edit | edit source]

The United States and Canada have placed sanctions on Venezuela. Donald Trump encouraged the EU to sanction Venezuela as well.[31]

In early 2019, the United States began an embargo of Venezuela's oil industry, the most important sector of its economy.[32]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ "Constitución de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela" (15 December 1999). Archived from the original.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Vijay Prashad (2008). The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World: 'Caracas'. [PDF] The New Press. ISBN 9781595583420 [LG]

- ↑ https://pt.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Resolucoesdo3oCongressoPT.pdf

- ↑ "How did Venezuela change under Hugo Chávez?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2023-04-24.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Saheli Chowdhury (2023-12-01). "Essequibo and Other Border Issues: Venezuela’s Territorial Losses to Imperialist Powers Through the Centuries (Part 1)" Orinoco Tribune. Archived from the original on 2023-12-02.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Saheli Chowdhuri (2023-12-03). "Essequibo and Other Border Issues: Venezuela’s Territorial Losses to Imperialist Powers Through the Centuries (Part 2)" Orinoco Tribune. Archived from the original on 2023-12-04.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "The Strategic Revolutionary Thought and Legacy of Hugo Chávez Ten Years After His Death" (2023-02-28). Tricontinental. Archived from the original on 2023-04-29.

- ↑ “Milestones: 1866–1898 - Office of the Historian.” 2023. State.gov. 2023.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Wilkins, Brett. “The History - and Hypocrisy - of US Meddling in Venezuela.” Telesurenglish.net. teleSUR. 2018. Archived 2023-03-07.

- ↑ "US Imperialism in Nicaragua and the Making of Sandino" (2020-02-21). Archived from the original on 2021-03-05. Retrieved 2022-06-25.

- ↑ https://www.mintpressnews.com/bolivarianism-vs-fake-us-democracy/38258/

- ↑ https://www.telesurenglish.net/news/Venezuelan-Government-Has-Built-4.2-Million-Homes-So-Far-20221028-0002.html

- ↑ Peru Will no Longer Support Blockade on Venezuela

- ↑ Blockade Against Venezuela Makes US Businesses Suffer: US Exports Dropped by 93% from 2012 to 2020 by Orinoco Tribune

- ↑ Andrew Buncombe (2019-04-26). "US sanctions on Venezuela responsible for 'tens of thousands' of deaths, claims new report" Independent. Archived from the original on 2022-02-19. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

- ↑ Venezuela Protesters Set 40 Tons of Subsidized Food on Fire (2017-06-30). TeleSur. Archived from the original on 2018-05-14.

- ↑ Venezuela's Economic War: Tons of Food Found Buried Underground (2015-08-17). TeleSur. Archived from the original on 2015-09-26.

- ↑ Food and Agriculture Organization. "Prevalence of undernourishment (% of population)" World Bank. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- ↑ Venezuela at UN: We must build 'new world without imperialism' by Ben Norton of Moderate Rebels on Substack Sep 22, 2021

- ↑ Carter Center > Venezuela > Monitoring Elections

- ↑ Roger G. Hood. The death penalty: a worldwide perspective, Oxford University Press, 2002. p10

- ↑ Determinants of the death penalty: a comparative study of the world, Carsten Anckar, Routledge, 2004, ISBN 0-415-33398, p.17

- ↑ Venezuela’s Strange Dictatorship by Orinoco Tribune

- ↑ Francisco Dominguez (2022-06-01). "MADURO’S SUCCESS: PRINCIPLED RESISTANCE TO IMPERIALISM PAYS OFF" Morning Star, Popular Resistance.

- ↑ "Ven App: Venezuela’s New Social Media" (2022-03-27).

- ↑ Benjamin Norton (2022-02-06). "CIA backed failed 2020 invasion of Venezuela, top coup-plotter says" Multipolarista.

- ↑ https://elpais.com/diario/2002/04/17/internacional/1018994403_850215.html

- ↑ https://www.rt.com/usa/497111-trump-ruined-venezuela-coup/

- ↑ Joe Parkin Daniels (2018-08-05). "Venezuela's Nicolás Maduro survives apparent assassination attempt" The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2022-07-15. Retrieved 2022-07-15.

- ↑ “Shortly after the drone attack, during an unrelated meeting on August 15, Venezuela came up, and Trump said to me emphatically, “Get it done," meaning get rid of the Maduro regime. “This is the fifth time I've asked for it,” he continued. I described the thinking we were doing, in a meeting now slimmed down to just Kelly and me, but Trump insisted he wanted military options for Venezuela and then keep it because “it's really part of the United States.””

John Bolton (2020). The Room Where It Happened: A White House Memoir: 'Chapter 9: Venezuela Libre'. Simon and Schuster. - ↑ Eugene Puryear (2017-10-11). "Is Venezuela Turning Further Left?" Liberation School. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22. Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- ↑ "PSL Editorial – End the U.S. economic war on Venezuela now!" (2022-11-28). Liberation News. Archived from the original on 2023-01-27.