More languages

More actions

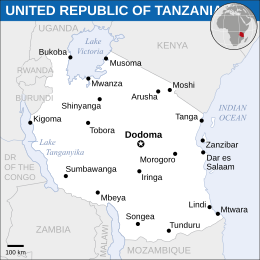

| United Republic of Tanzania Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania | |

|---|---|

| |

| Capital | Dodoma |

| Largest city | Dar es Salaam |

| Official languages | Swahili English |

| Dominant mode of production | Capitalism |

| Area | |

• Total | 947,303 km² |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 65,642,682 |

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa bordering Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique. The nation came to be called "Tanzania" when independent Tanganyika and Zanzibar formed a united republic in 1964.[1] Dodoma is the capital city, while the former capital Dar es Salaam is a major sea port and commercial city.[2][3]

Tanganyika had undergone two periods of formal colonial rule by European powers, first by Germany as part of German East Africa from 1888-1919, and second by Britain from 1919-1961.[1] Zanzibar had been a sultanate since 1840, and a British protectorate from 1890-1963. After independence from Britain, the sultanate was overthrown in a 1964 revolution.[4]

Over 120 languages are spoken in Tanzania. Kiswahili (also called Swahili) is the national language.[5] Tanzania is also religiously diverse, with Christianity and Islam being the most prevalent religions, along with communities practicing traditional belief systems and other major world religions. The populations of Zanzibar and Pemba are predominantly Muslim.[6]

Tanzania is the location of one of the largest volcanos in the world and the highest point in Africa, Mount Kilimanjaro.[7]

History

Early history

Prehistoric human habitation in the area of what is now Tanzania stretches back to include not only anatomically modern humans, but also archaic human ancestors and predecessors dating back millions of years. For example, Ngorongoro Conservation Area in Tanzania contains various fossils and artefacts associated with some of the earliest human ancestors, including early hominid footprints dating back 3.6 million years.[8][1][9]

Approximately 10,000 years ago, Tanzania was populated by hunter-gatherer communities who spoke Khosian, joined about 5000 years ago by Cushitic-speaking people. About 2000 years ago, Bantu speaking people began arriving from western Africa in a series of migrations. Later, Nilotic pastoralists began arriving in the region.[1]

By 1500, most of the people of western Tanzania were organized into chiefdoms, with chiefs, in general, being responsible for making political decisions, handing down legal rulings, and keeping the community safe.[10]

Tanzania's eastern side is coastal, lying on the Indian Ocean. This position made the area a point of contact between many different cultures and nations for many centuries via trade routes, which has had various impacts on the region's history. Trade along the East African coast by Bantu speaking peoples living there in the first centuries of the 1st millennium during the region's Iron Age resulted in people moving in greater numbers to the coast, spreading influence in art and architecture, along with the Bantu language of Swahili.[11]

Over time, a number of city-states had arisen on the East African coast. The influence of Islam and Arabic came to the coast with Arab traders in the 7th century. At the height of their influence in the 12th-15th century, the coastal city-states traded with African tribes extending to inland locations (such as to Great Zimbabwe via Sofala), as well as extended to Arabia, Persia, India, and China across the Indian Ocean.[11]

Portuguese disruptions

When the Portuguese arrived in the region, they aimed to achieve total control of the Indian Ocean trade networks. The Portuguese sank ships, destroyed cities, built forts, and exploited rivalries between states, creating major disruptions in the long-established trade networks, as well as attempting to move inland and causing similar disruptions to other peoples, such as targeting the Mutapa state in what is now Zimbabwe. Over time, the Portuguese shifted much of their focus to what is now Mozambique, the southern neighbor of modern Tanzania.[11][12]

Colonization

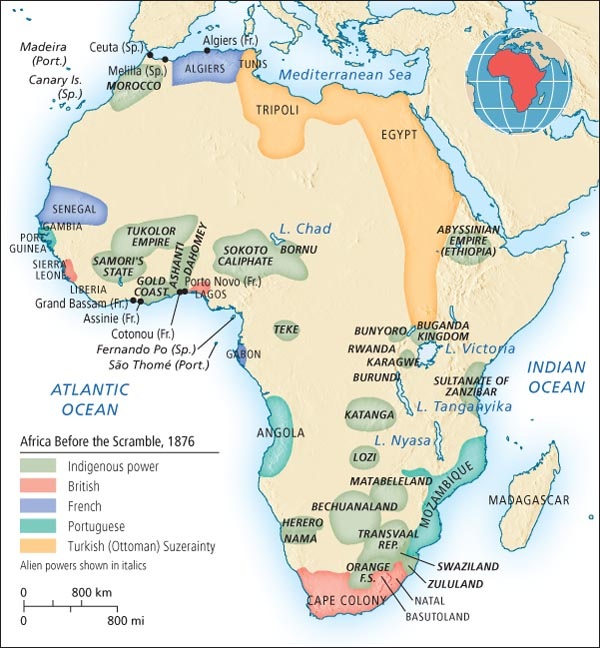

The Portuguese disrupted and colonized the Tanzanian coast for approximately two centuries (circa 1500-1700) until they were ousted by a coalition of the local people and the Omani Arabs. Following this, the Omani Arabs occupied Zanzibar and the coast as well as claiming some inland areas.[13]

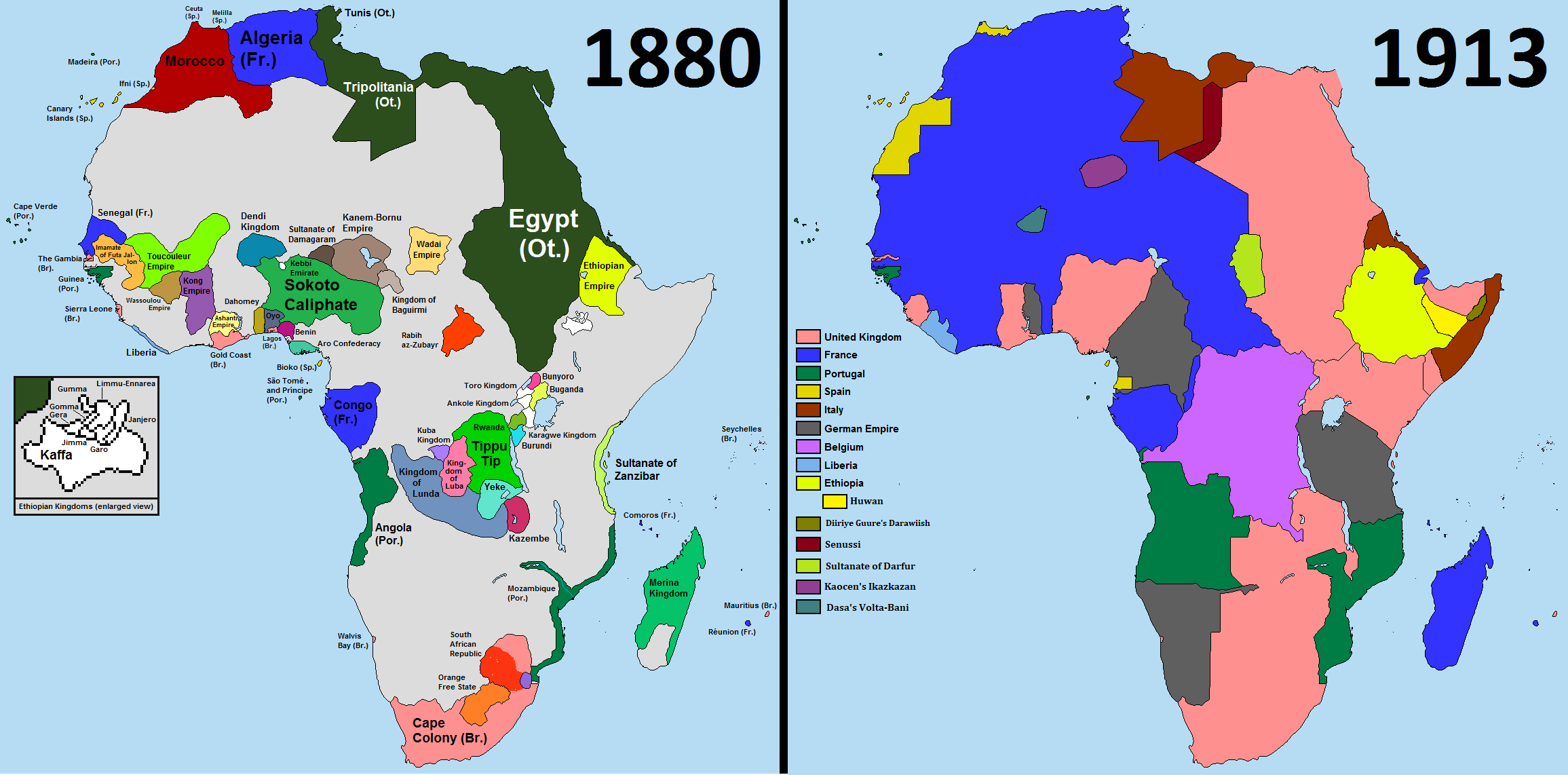

By the 1800s, there was an increase of British, French, and German activity in the region. The British were active in the Indian Ocean trade. The French were purchasers of slaves for their colonies in the region (though the French officially banned the slave trade in 1822). Europeans began exploring the interior of the country in the mid-1800s, including groups of Christian missionaries. Germany began to establish their presence on the mainland in the late 1800s,[10] largely through the efforts of the German Colonization Society founded by future colonial governor, Dr. Karl Peters.[14]

Tanzania underwent two periods of formal colonial rule by European powers, first by Germany as part of German East Africa from 1888-1919, and second by Britain from 1919-1961. The region was made a League of Nations mandate after Germany's defeat in the First World War, with colonial control transferred to the British. Under British rule the region was renamed to Tanganyika Territory. Following the Second World War, Tanganyika became a "trust territory" under UN monitoring, with Britain as its administering power.[15][16][1]

German rule (1888-1919)

Germany ruled the mainland of Tanzania as "German East Africa" until the end of the First World War, while Zanzibar became a British protectorate. Initially, German colonial rule was via the imperial charter of the German East Africa Company, but by 1891, governance was changed over to the German government itself.[10]

The Germans used forced labor to construct infrastructure such as roads and railway systems, and instructed villages to grow cotton as a cash crop instead of traditionally grown food crops, and subjected the population to high taxation, enforced through repression and violence. The policies and practices of German rule were extremely unpopular with the local people, and the German colonizers were met with significant resistance.[10][14]

In an analysis of the political economy of the colonial period in what is now Tanzania, historian Walter Rodney wrote that German East Africa was a "typical colonial situation in which taxes were imposed on Africans not so much for the revenue which resulted but as a means of propelling them into the labour market and the money economy, and thereby drawing off the surplus." He further wrote that the introduction of such mechanisms for alienating the product of people's labor "inevitably evoked African bewilderment and hostility, which in turn were met by European force exercised in the name of law and order."[17]

Plantations and labor conditions

According to Walter Rodney's analysis, plantations were "the most important innovation of the formative period of the colonial political economy under German hegemony", being "a socio-economic entity ideally suited to metropolitan capitalist investment in the colony" as well as fitting racist notions of supremacy. Plantations required large amounts of land, capital, and African labor, along with "a small elite corps of non-African supervisory staff". The local population resisted plantation work, and coercion and abuses were rampant in recruitment.[17] Rodney describes the extremely poor labor conditions of the plantations as follows:

Wages for plantation labourers and other workers were initially low, and they were depressed as soon as the colonial state machinery pushed more Africans on to the labour market, as was the case by 1903. Living and working conditions were extremely poor; and any attempt to escape was branded as 'desertion', and treated as a criminal offence liable to imprisonment. Africans who were in the employ of Germans suffered day to day abuses and brutality, and these first decades of the German East African colonial regime were notorious for the frequency and severity of whippings applied by private employers and by state officials.[17]

While the productivity of plantation labor was low, it was a profitable system under colonial conditions because the employer was not responsible for providing the worker a living wage to feed himself and his family and left the burden of subsistence to the countryside from where the laborer was recruited, an arrangement very profitable for the colonizing capitalists while indigenous economies were robbed of the labor of those who were away working at plantations.[17]

Maji Maji Uprising (1905-1907)

The Maji Maji Uprising (also called the Maji Maji War or Rebellion) occurred from 1905-1907. It was a significant resistance to the invasion by the Germans, with tensions boiling over after a drought worsened the already harsh conditions created by German rule. The uprisings began with attacks on German outposts and destroying cotton crops.[10]

The rebellion spread all throughout the colony, eventually involving 20 ethnic groups who wanted to oust the colonizers. In August 1905, several thousand warriors attacked a German stronghold, but failed to overrun it. The German response was brutal, killing men, women, and children and adopting famine as a weapon. It is estimated that between 75,000 and 120,000 Africans were killed and many more were displaced from their homes during this two-year period of revolt against German rule.[10][14]

Although the uprising was ultimately unsuccessful, the German government was pressured to institute some reforms, such as domestically creating a formal political organ in Germany which would be answerable to parliament in governing the colonies, as well as creating District Commissioners in the colonies to attempt to have more government supervision of labor relations. However, as noted by Walter Rodney, a "more liberal phase was a prerequisite for the entrenchment of colonial capitalist relations" and many of the harsh labor conditions and low wages continued, as "the law was still an instrument of the employing class between whom and the government the contradictions were secondary."[17] Despite these outcomes, the uprising would become an inspiration for later freedom fighters against European colonial rule.[14]

First World War

After the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, British and Belgian troops occupied most of German East Africa. With the defeat of Germany, the League of Nations gave Britain control of the region that is now Tanzania, while the areas that are today Rwanda and Burundi were handed over to Belgian rule.[10]

Early British rule (1919-WWII)

When Britain took over control of part of former German East Africa following the First World War, they renamed it to Tanganyika. Like most of their colonies, the British established control of Tanganyika under the policy of "indirect rule" wherein colonial administrators ruled through local leaders. An article by the African Studies Center at Michigan State University summarizes indirect rule and its effects in Tanganyika as follows:

Basically stated, indirect rule was a way for colonial administrators to rule through local African leaders. In this way the British could exert their authority over a colony with minimal resources and also avoid direct confrontation with the larger African population. This approach, however, assumed that all groups being governed had a centralized, hierarchical system of political organization, that is to say a leader or governing structure with authority over the whole group. This was not the case with all ethnic groups in Tanganyika. Consequently, the British had to impose an invented hierarchy on these groups, and this led further destabilization in the colony.[10]

As was described in a paper by Jwani Timothy Mwaikusa, "Colonialism [...] distorted and altered the role and functions of indigenous institutions and traditional authorities to serve colonial purposes [...] even the sentiments against colonial rule sometimes manifested themselves in forms of defiance against tribal institutions and authorities."[18]

The Native Authority Ordinance of 1926 established "Native Authorities" considering traditional chiefs to be rulers of their tribes and giving them some powers of legal authority in their jurisdictions. As one modern-day Tanzanian government pamphlet describes, "The chiefs were groomed in such a way as to prop the colonial government."[19]

In 1929, the Tanganyika African Association (TAA) was formed as a social organization; it would later be reoriented in the 1950s to become the political organization known as Tanganyika African National Union (TANU).[20]

Second World War

Trust territory under British rule (1946-1961)

Following the Second World War, along with the other remaining League of Nations mandates, Tanganyika became a United Nations (UN) trust territory, with Britain as its administering power.[16][21] Under the terms of the trust agreement, Britain nominally had the responsibility of preparing Tanganyika for independence, and was considered accountable to the UN's Trusteeship Council in that regard, though in practice the British governed Tanganyika similarly to their other colonies.[18] As a trust territory, the government of Tanganyika had to report every three years to the UN's Trusteeship Council as well as be periodically assessed by a visiting mission from the Council to study the trust territory's conditions.[22]

In 1953, a Local Government Ordinance was passed, creating municipal, town and district councils.[19] The colonial government sought to secure the position of the minority immigrant races in the local government system by promoting a policy of "multi-racialism", in which voters would elect candidates according to a race-based tripartite system of electing Europeans, Asians, and Africans in fixed proportions, and which vastly underrepresented Africans compared to Tanganyika's actual demographics. It was an unpopular policy and was later opposed by the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU), although they cooperated with it in elections held under the British colonial authority, while voicing their disapproval of it.[18][22]

Independence movement and TANU

In the 1950s, Julius Nyerere had been elected Territorial President of the semi-political, semi-cultural organization Tanganyika African Association (TAA). Nyerere came to see TAA as inadequate for challenging the colonial authorities, and thus began drafting a new constitution to reorient the organization's objectives and policy. At TAA's annual conference in July 1954, the organization was renamed to Tanganyika African National Union (TANU).[20][23]

Workers in the shipping, post, diamond, and rail industries led a series of strikes in 1958 to win independence from Britain.[24]

Elections (1958-1960)

The first phase of direct elections in Tanganyika took place in September 1958 and the second phase took place in February 1959, with TANU sweeping the polls. Conversely, the United Tanganyika Party (UTP) formed by the British governor of Tanganyika had little success and won no seats.[22] In 1959, it was announced that a general election would be held the following year. When the 1960 elections were held, TANU again won with widespread support. This was soon followed by official proceedings for internal self-government in May 1961, followed by official independence in December 1961.[18]

Tripartite "multi-racialism" policy

At the time of the 1958-1959 elections, the British governing authority's election system maintained that three races (European, Asian, and African) be elected in a fixed ratio, a policy called "multi-racialism" which was criticized by TANU and upheld by UTP. The criticism arose due to the 1:1:1 ratio being highly disproportionate to the actual demographics of the country, Africans being about 98% of the population. Thus the "multi-racialism" policy served to hinder and prevent African power in governance.[22][18]

TANU's unpopular rival party, UTP, in a communication with the UN, described its own policy as "the most liberal in Africa" and believed that "self-government could not be regarded as an end in itself" and deemed TANU to be "a racialist movement based on a colour bar in reverse". UTP painted "multi-racial" policy as necessary for racial harmony in Tanganyika and for "the political development of the African on responsible lines", considering it "morally wrong" to accept the idea of African "nationalist-racial doctrine" of Africans having the "right to 'rule or misrule'".[25]

In these elections under the "administering authority" of Britain, in which voters had to elect people from each race, TANU successfully mobilized voters to elect only TANU-approved candidates for the Asian and European seats.[26]

Sofia Mustafa, who ran as a TANU-approved candidate for the Asian seat in her province, wrote in her memoir about this policy of "multi-racialism" stating that it served to entrench the three races as separate entities, in contrast to a system which considers "all inhabitants of Tanganyika as citizens of Tanganyika".[22] An analysis by Professor Cranford Pratt summarized that the effort to entrench special minority representation "aroused racial antagonism and endangered rather than safeguarded the interest and security of these minorities. It is only after this effort has been abandoned that race relations have improved and the minorities have regained a measure of their earlier security."[26]

Internal self-government

In 1960, general elections were held and TANU again showed the mass support behind it, winning 70 out of 71 Legislative Council seats–the remaining seat also being won by a TANU member who had run as independent. These events were followed over the next year by official proceedings with the British "administrating authority" toward internal self-government, followed by formal independence on December 9, 1961.[18]

Independence of Tanganyika (1961)

Tanganyika attained formal independence on December 9, 1961, with Julius Nyerere as Prime Minister. In 1962 a new constitution was implemented and Nyerere became the first President.[16]

Nyerere writes that TANU became officially committed to the building of a socialist country since early 1962.[27] A 1962 pamphlet published by TANU titled "Ujamaa – The Basis of African Socialism" details the "socialist attitude of mind" and explains Ujamaa, which draws inspiration from traditional African society and the extended family and calls for "rejecting the capitalist attitude of mind" brought on by colonialism. As stated in the pamphlet, "We must, as I have said, regain our former attitude of mind–our traditional African socialism–and apply it to the new societies we are building today."[28][27]

According to a work released in 1968 by Nyerere, the 1962 pamphlet had not been made easily available to the people of Tanzania at the time it was published, and thus many active party workers, teachers, and civil servants remained unclear about the socialist principles they were responsible for promoting and serving. He states that this did not prevent the government and Party from pursuing socialist policies, but that over time, the absence of a generally accepted and easily understood statement of philosophy and policy was allowing some government and Party actions which were not consistent with the building of socialism.[27]

Zanzibar Revolution (1964)

See main article: Zanzibar Revolution

The Sultanate of Zanzibar formally attained independence from Britain on December 10, 1963. A month later, on 12 January 1964, a revolution began which led to the overthrow of the sultan. It was described by one historian as a revolution which "replaced a conservative Arab-dominated regime with one that espoused the principles of African nationalism and radical socialism and that developed close ties with communist bloc countries."[29]

United Republic of Tanzania (1964-present)

On April 26, 1964, the Republic of Tanganyika and the People's Republic of Zanzibar were united, forming the United Republic of Tanzania.[16]

In the early 1960s, Tanzania did not largely intervene with small farmers besides improving irrigation.[24]

In 1965, Tanzania formally became a one-party state.[18]

From 1965 to 1968, Tanzania broke off diplomatic relations with Britain due to their policy on Rhodesia's (now Zimbabwe) "unilateral declaration of independence" (UDI) under white settler minority rule.[23]

Arusha Declaration (1967)

In 1967, President Nyerere announced the intent of forming a socialist state in the Arusha Declaration. His administration nationalized key industries while developing agriculture and industry. All unions were merged into the National Union of Tanganyika Workers.[24][27] A process of forming collective villages, also called ujamaa villages, was also envisioned and clarified in various speeches and writings.[27][24]

Rural development plans

After the Arusha Declaration was made, which Nyerere described as "a declaration of intent"[30] a policy booklet was published in September 1967, titled "Socialism and Rural Development".[31] The booklet explained various details of the ideas underpinning the goals for rural development and emphasized the importance and necessity of democratic decision-making among peasants for how to develop their villages, as well as making assessments of the limitations of Tanzania's development level and available resources at the time.[31]

The booklet also explained that traditional ideas were to be drawn upon and combined with modern ones so as to achieve decent living standards for all, writing, "We must take our traditional system, correct its shortcomings, and adapt to its service the things we can learn from the technologically developed societies of other continents."[31] Among the major shortcomings of traditional society, the booklet identified inequality of women, which was deemed inconsistent with socialist conceptions of equality; and the other shortcoming being that though traditional society displayed "an attractive degree of economic equality [...] it was equality at a low level. The equality is good, but the level can be raised."[31] A few months later, in a speech in January 1968, Nyerere emphasized that "the policy outlined in 'Socialism and Rural Development' is not the work of a month or a year; it is the work for ten or twenty years ahead."[32]

Author Vijay Prashad, in his work The Darker Nations which explores setbacks in the Third World revolutionary movements' struggles to enact their agendas, described the ujamaa villages as having two major flaws in his view, firstly that they were not constructed so as to "refashion the gendered aspects of social power" and thus failed to deal with patriarchal relations, and secondly, that the policy left no time to persuade the peasantry, and thus often relied on force. Prashad notes that Tanzania's experience is consistent with "a vast number of examples of Third World development", in what he describes as "Third World socialism in a hurry" born out of the need for nations to develop rapidly.[24]

Debates at University of Dar es Salaam

Activist and historian Walter Rodney, who had visited Tanzania in 1966, came to live in Tanzania from 1969 to 1974, after having been banned from Jamaica. He taught history and political science at the University of Dar es Salaam,[33] and also wrote articles in publications such as the joint magazine of the TANU Youth League's branch and University Students African Revolutionary Front (USARF),[34] called Cheche (meaning "spark" in Swahili), as well as in TANU's party paper The Nationalist,[35] and engaged in political discussions and debates, including with a TANU cabinet minister over Tanzania's economic direction. Though some of Rodney's statements drew strong criticism from Nyerere, Rodney continued to teach at the university.[33] It was also during this time that Rodney wrote his 1972 book, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa.[35]

Issa G. Shivji, another individual who had published in Cheche at the time, remarked in a 2021 interview regarding the debates, which at times were highly critical of the methods in the path to socialist construction being taken in Tanzania, that "we had some very great debates in Tanzania [...] Mwalimu did not like us but he tolerated us. He tolerated and sometimes even came to the campus to debate with us [...] there was a kind of love and hate relationship between the radical students on campus and Mwalimu Nyerere."[36] After the third issue of Cheche was published, the publication was banned and USARF deregistered, and the students re-named their journal MajiMaji and many of the former USARF leadership went into the TANU Youth League and continued their activities.[35]

TAZARA Railway

The TAZARA Railway is a railway between Tanzania and Zambia, which was built through a combined effort of Tanzania and Zambia assisted by the People's Republic of China, constructed from 1968 to 1976[37] and enabling landlocked Zambia to have an outlet to the sea when colonial and settler governments in neighboring countries had attempted to cut off Zambia's sea access.[38]

Though Zambia and Tanzania had first approached Western countries for assistance to build the railway, the imperialist powers turned them down.[38] On the other hand, China offered to provide the finances for construction via interest-free loans,[37] expertise and equipment, workshops and training facilities. At the height of construction, the workforce rose to 38,000 Tanzanian and Zambian workers and 13,500 Chinese technical and engineering personnel.[38] Main construction began in 1970, with the track crossing over from Tanzania to Zambia by 1973, and reaching Kapiri-Mposhi in 1975, two years ahead of schedule. Trial operations were followed by full operation in 1976.[38]

The Tanzania-Zambia Railway Authority's website hails the effort as heroic, with its difficulties being immense:

It is not easy to fathom the extent of heroism and ingenuity displayed by both the Chinese people, represented by their great engineers and workers and the Tanzanian and Zambian people, who joined the Chinese for the construction of this unique railway. The hostile environment, through which the line often had to pass, did not deter them. [...] Over 160 workers, among them 64 Chinese, died during the construction of the railway.[38]

The TAZARA website also describes the background of the railway, explaining that though colonial governments had themselves considered the idea of constructing such a railway previously, they had deemed it "economically unjustifiable"; however, "it was apparent that these conclusions were laced with political thinking. The settlers feared that such a rail link would affect their interests in the region."[38] With the Rhodesian settler government's "unilateral declaration of independence" (UDI), "the Smith regime tried to intimidate Zambia out of her support for the liberation struggle by cutting her only outlet to the sea". Thus the leadership of Zambia and Tanzania sought to construct the railway so that Zambia would have an outlet which would not be under colonial control.[38]

Sixth Pan-African Congress (1974)

The Sixth Pan-African Congress was held in Dar es Salaam in 1974, from June 19th to 27th.[39]

Formation of Chama cha Mapinduzi (1977)

In February of 1977, TANU and ASP (the political party in Zanzibar) merged to form Chama cha Mapinduzi (CCM).[18]

Tanzania–Uganda War (1978-1979)

Neoliberalization (circa 1980s-present)

In a 2021 interview, Professor Issa G. Shivji described the last years of Nyerere's administration (1980-1985) as an "extremely difficult" period. He described it as a period where the IMF and World Bank "mounted an offense" and started imposing increasingly neoliberal conditions on Tanzania, pointing out that this was the Thatcher-Reagan era.[36] Shivji describes:

It was rationing, corruption became very high, people took advantage of the crisis situation to make a fast buck, the bureaucracy began to flex muscles, and the foreign governments, the so-called "donor" governments, as well as their organizations – like the World Bank, International Monetary Fund – also now, became stronger, and took an offense. Until then, they were on the defense. But now they mounted the offense.[36]

In 1985, Nyerere stepped down from government, which was followed by further neoliberal policies and privatization to foreign capital over the following decades. In Shivji's analysis, the following ten years after Nyerere stepped down was a "transition period from Mwalimu's nationalism to full-fledged neoliberalism" under president Mwinyi (in office 1985-1995).[36] In 1992, the constitution was amended to allow the formation of opposition parties, with the Eighth Constitutional Amendment Act coming into force in July 1992, putting an end to the one-party system.[18] The first multi-party general election was subsequently held in October of 1995.[18] Mwinyi's administration was followed by what Shivji described as a "consolidation of neoliberalization" under president Mkapa (in office 1995-2005) with a high degree of privatizations, in most cases to foreign capital. He described the following administration of Kikwete (in office 2005-2015) as laissez-faire.[36] Shivji describes the effects of such policies have had on Tanzania:

Our society got extremely polarized between a small filthy rich class and large majority of the poor, even the middle class sinking into poverty. Inequality increased, most social services were outsourced and privatized, like education, health, and so on and so forth.[36]

In Shivji's view, these neoliberal policies have led to a populist backlash which is more right-wing than left-wing due to the weakness of the left; this has resulted in Tanzania having "some kind of resource nationalism, but very haphazard, not directed."[36]

Economy

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "Brief History." Embassy of the United Republic of Tanzania, Berlin, Germany. Archived 2024-04-21.

- ↑ "Country Profile." Tanzania Embassy in Berlin, Germany. Archived 2024-04-07.

- ↑ "City Profile." Dar es Salaam City Council. The United Republic of Tanzania President's Office Regional Administration and Local Government. Archived 2024-06-07.

- ↑ Ayman Tarek Elkholy (2016-03-27). "Sultanate of Zanzibar (1856–1964)" BlackPast. Archived from the original on 2024-06-07.

- ↑ "People and Culture." Tanzania Embassy in Berlin, Germany. Archived 2024-05-17.

- ↑ "Module Twenty Six, Activity One: Introducing Tanzania; its History, Geography, and Cultures". Exploring Africa.

- ↑ "Kilimanjaro National Park". UNESCO . Archived from the original on 2024-05-23.

- ↑ "Olduvai Gorge: Overview." Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority, The United Republic of Tanzania. Archived 2024-04-17.

- ↑ "Ngorongoro Conservation Area." UNESCO.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 "The History of Tanzania." Module Twenty Six, Activity Two, Exploring Africa. Archived 2024-06-03.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Cartwight, Mark. "Swahili Coast." World History Encyclopedia, 2019-04-01. Archived 2024-05-29.

- ↑ Mark Cartwright (2021-07-15.). "The Portuguese in East Africa" World History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2024-04-30.

- ↑ Mulokozi, M.M. "Study report on the common oral traditions of Southern Africa: a survey of Tanzanian oral traditions." UNESCO, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 1999. Archived 2024-06-02.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Alys Beverton (2009-06-21). "Maji Maji Uprising (1905-1907)" BlackPast. Archived from the original on 2024-02-22.

- ↑ McCarthy, D. M. P. "Colonial bureaucracy and creating underdevelopment: Tanganyika, 1919-1940." The Iowa State University Press, 1982.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 "Every December 9th : is the Commemoration of Tanzania Mainland Independence Day." Embassy of Tanzania in Tokyo, Japan, 2023-12-09. Archived 2024-05-30.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Walter Rodney (1974). The political economy of colonial Tanganyika, 1890-1939.. [PDF] Dakar: United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, African Institute for Economic Development and Planning (IDEP).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 18.8 18.9 Jwani Timothy Mwaikusa (1995). Towards Responsible Democratic Government: Executive Powers and Constitutional Practice in Tanzania 1962-1992. [PDF] Law Department, School of Oriental and African Studies.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 History of Local Government in Tanzania. [PDF] United Republic of Tanzania: President's Office Regional Administration and Local Government (PO-RALG).

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Gabriel Ruhumbika (editor) (1974). Towards Ujamaa: Twenty Years of Tanu Leadership. East African Literature Bureau.

- ↑ "List of former Trust and Non-Self-Governing Territories". United Nations.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 Sophia Mustafa (1961). The Tanganyika Way. Dar es Salaam: East African Literature Bureau.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Chambi Chachage, Annar Cassam. "Africa's Liberation: The Legacy of Nyerere." Pambazuka Press, 2010.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 Vijay Prashad (2008). The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World: 'Arusha' (pp. 191–6). [PDF] The New Press. ISBN 9781595583420 [LG]

- ↑ Brian Willis, United Tanganyika Party. "Communication from the United Tanganyika Party concerning Tanganyika." United Nations Trusteeship Council document, 25 June 1957.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Cranford Pratt (1960). "Multi-Racialism" and Local Government in Tanganyika., vol. Volume 2, Issue 1. Race. doi: 10.1177/03063968600020010 [HUB]

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 Nyerere, Julius K. "Ujamaa: Essays on Socialism." Oxford University Press, 1968.

- ↑ Nyerere, Julius K. (1962). Ujamaa: The Basis of African Socialism. [PDF]

- ↑ Ian Speller (2007). An African Cuba? Britain and the Zanzibar Revolution, 1964. [PDF] Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. doi: 10.1080/03086530701337666 [HUB]

- ↑ Julius K. Nyerere (1968). Ujamaa -- Essays on Socialism: 'The Purpose is Man: A speech at Dar es Salaam University College, 5 August 1967'. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Nyerere, Julius K. (1968). Ujamaa -- Essays on Socialism.: 'Socialism and Rural Development: Policy booklet published in September 1967'. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Nyerere, Julius K. (1968). Ujamaa -- Essays on Socialism: 'Progress in the Rural Areas'. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Chinedu Chukwudinma (2022-04-07). "The Mecca of African Liberation: Walter Rodney in Tanzania" MR Online, originally published by ROAPE (Review of African Political Economy). Archived from the original on 2024-06-06.

- ↑ The Silent Class Struggle (1974). Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Publishing House.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Shivji, Issa G. (2012-12-01). "Remembering Walter Rodney" Monthly Review. Archived from the original on 2024-06-07.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 36.5 36.6 Tshisimani Centre for Activist Education (2021-12-09). "60 Years of Tanzanian Independence, with Prof Issa Shivji". YouTube.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Huang Peizhao (2023-08-01). "Tanzania-Zambia Railway: A Railway of Friendship, Prosperity" People's Daily Online. Archived from the original on 2023-08-12.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 38.5 38.6 "Our History". Tanzania-Zambia Railway Authority. Archived from the original on 2024-06-07.

- ↑ Farmer, Ashley. "Black Women Organize for the Future of Pan-Africanism: The Sixth Pan-African Congress." African American Intellectual History Society, 2016-07-03. Archived 2024-06-06.