References to be used[1][2][3]

This page is about the history of China until the establishment of the People's Republic. For the history of the People's Republic of China specifically, see History of the People's Republic of China.

The history of China dates back to more than 5000 years ago.[4] China, like all state societies, went through the slavery, feudal and capitalist modes of production until the establishment of the People's Republic in 1949.[citation needed]

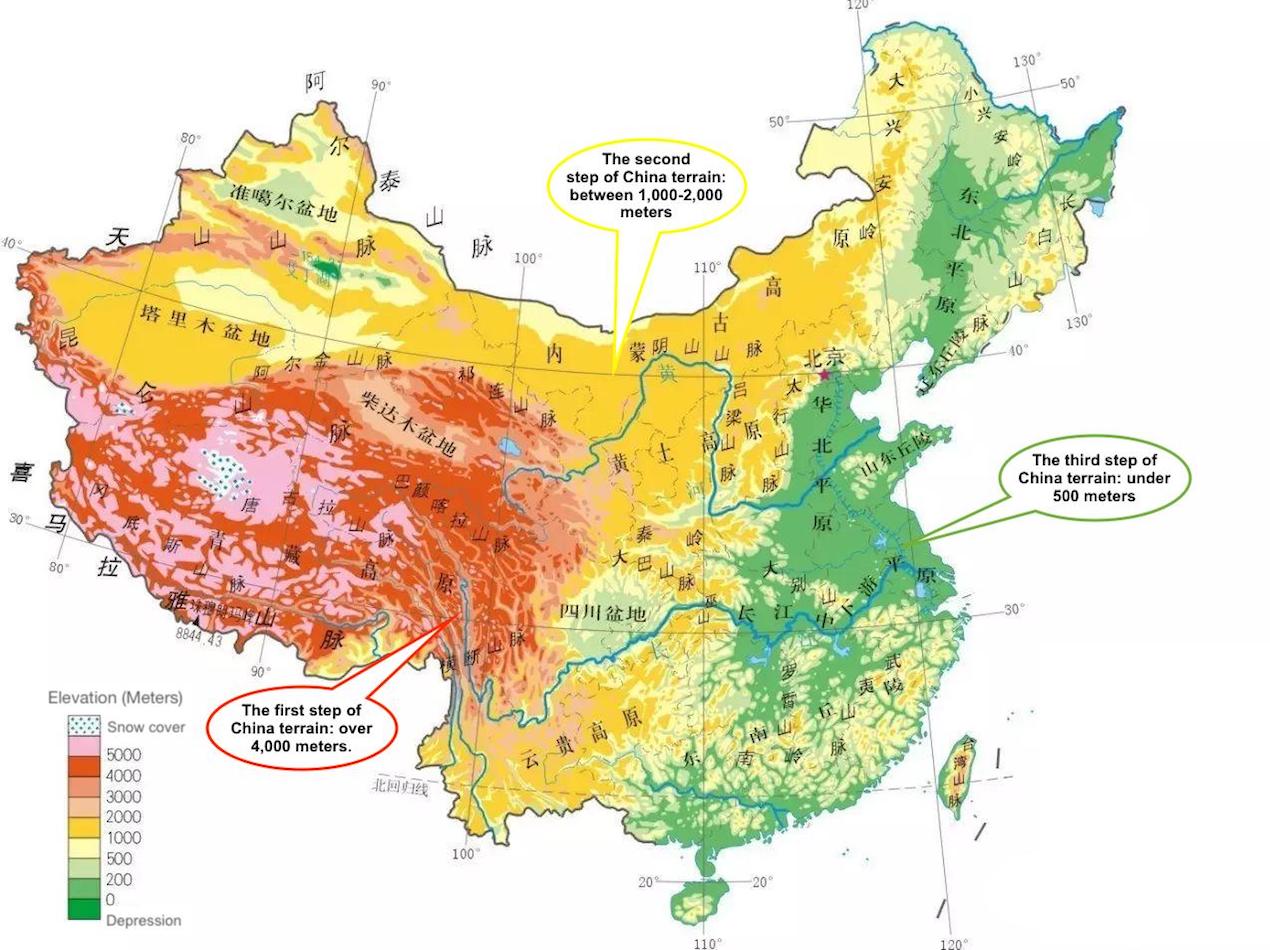

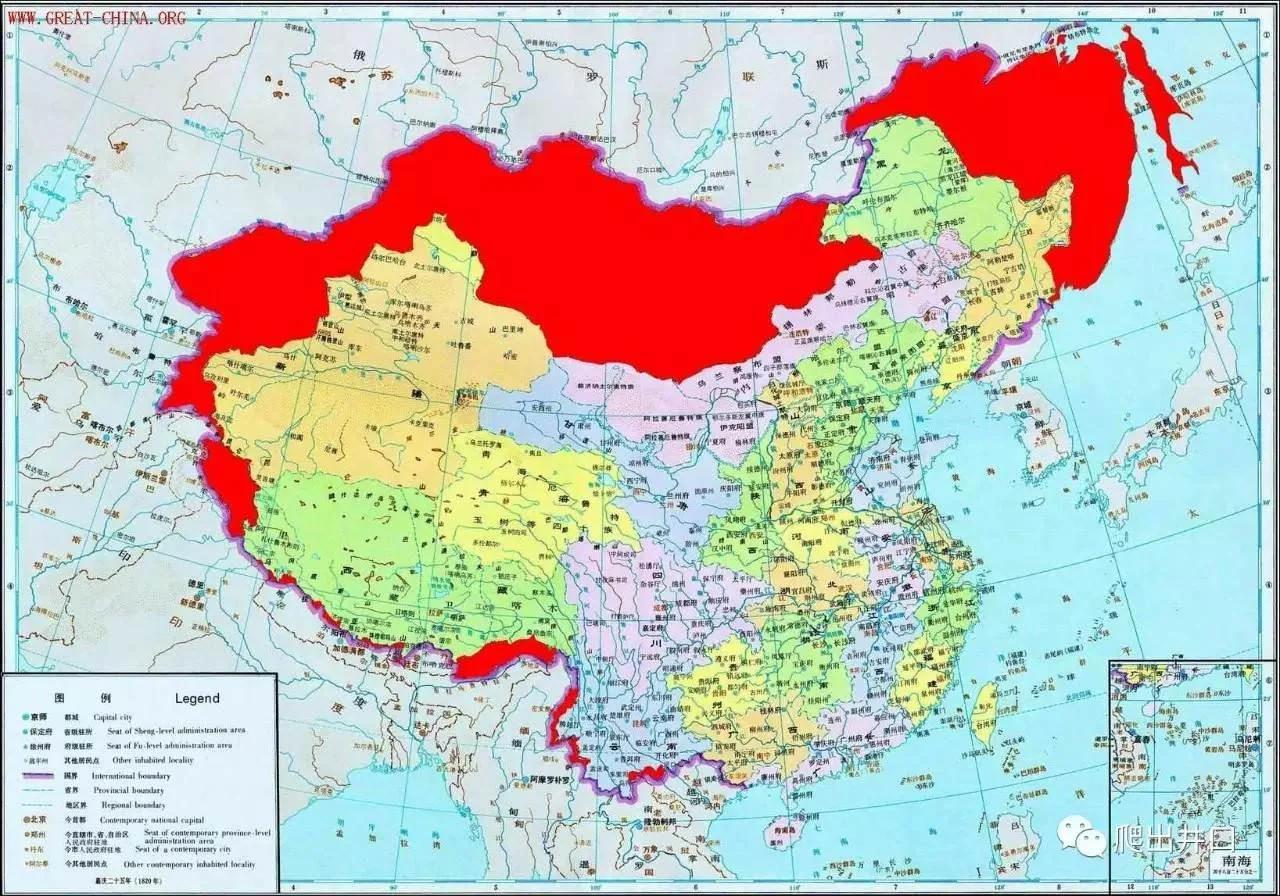

Geography of China

According to Dr. Ken Hammond of the New Mexico State University, to understand how China (Zhōngguó, 中国, literally the "Middle Empire") materially developed throughout its history, it's important to understand the geography of the country.[4]

The North China plain, at the mouth of the Yellow river (Huáng Hé, 黄河), is to this day the agricultural heartland of China thanks to its low and flat terrain as well as the irrigation it receives from the Yellow river, and this plain is where Chinese civilisation first emerged.[4]

Conversely, the South China plain is a region of hills and valleys, mostly south of the Yangtze river. Settlements in the south are divided off one another by these mountains, and river valleys tend to be where permanent settlements developed.[4]

Rivers

Two important Chinese rivers find their source in the Tibetan plateau: The Yellow river and the Yangtze river.[4]

The Yellow River has shaped China for millennia. It snakes around Northern China until it empties into the Yellow sea, in the province of Shandong. While the Yellow River has historically represented a challenge to China as it was prone to flooding, these floods brought with them fertile soil and irrigation to crops, and the river has always been primordial to the development of Chinese civilisation.[4]

The Yangtze River (Cháng Jiāng, 长江, literally "long river") further in the south has also been very important to Chinese civilisation historically, but less so than the Yellow river. The Yangtze river, while prone to flooding both historically and in the modern day, has played a huge part in agriculture and sustaining life around it. The Yangtze river's flooding was dealt with in part through the Three Gorges dam.[4]

Prehistoric and early historic period

Traditional Chinese historiography

Chinese history has been studied by its people since Ancient times, and forms the basis of the traditional Chinese historiography. Their history begins around the time of the sage kings, or sage emperors (), figures of antiquity and prehistory (i.e. that predate writing). Thus historiography, which is the writing of history itself, has been going on in China for millennia. Dr. Ken Hammond notes that in many places, this historiography has been proven correct thanks to archeological records found after the fact.[5]

Sage kings Yao and Shun

A notable king in traditional Chinese historiography is Yao (尧), who was the first to pass the throne down to a successor. Yao's own son was considered to be weak and decadent, and so Yao scoured his kingdom until he found Shun (帝舜) who had strong moral virtues and picked him as his successor.[5]

The story of king Yao is an interesting contrast to the practices of succession in other historical dynasties in China, where succession was kept to a single family. According to Dr. Ken Hammond, this story is important in Chinese historiography because it highlights a quality, having a strong moral character, that was considered important in Chinese history.[5]

This story, as well as the virtue of morals, would later found the premises for the Mandate of Heaven (Tiānmìng, 天命, literally Heaven's command) in China.[5]

Early societies

According to Dr. Ken Hammond, the population of China itself has evolved in complex ways.[4] The earliest people who would later call themselves the Chinese (Zhongguo ren, literally People of the Middle Country) lived in the North China plain. The earliest societies to emerge from this area were confederations of numerous tribal groups who defined themselves in contrast to those who were not Chinese, i.e. people who were not civilised. A number of terms exist in Chinese to define these people that are best translated to as "barbarians" in English (barbarians being what the Ancient Greeks similarly called any people who were not Greek).[5]

Excavated pottery remains suggest that a single culture came to dominate the whole of the North China plain some 4000 to 6000 years ago. Characteristic pottery was discovered as originating from Dragon Mountain (Lóngshān, 龙山,), and later showed up in other archeological sites.[5]

Writing

One key element that made this first Chinese society define themselves as civilised (as opposed to what they defined as their barbarian neighbours) was a system of writing, which their neighbours did not possess. There is not much transitional evidence to the emergence of writing in China. That is to say, archeological evidence shows that once writing appears in China, it showed up as a fairly fully developed system, suggesting that writing appeared fairly quickly.[5]

Mass migration

As Chinese civilisation expanded, neighbouring peoples, particularly in the South, were either displaced or assimilated. The Vietnamese and Thai people, for example, formerly lived in southern China and were displaced as part of this expansion to the South.[5]

Some of these populations were forced further west, on higher elevation, and have remained there since then. Today, they are generally called hill tribe communities, and many of these groups retain distinctive identities in China: they retain their own language, their own cultural practice, and their own religion. Today, they constitute around 5% of the population of China. There are 54 such officially recognized ethnic minorities in China.[5]

This process happened around 2500 to 2000 years ago.[5]

The first slave states

The emergence of bronze was critical to China's future development. Bronze gave rise to an industry of mining, smelting, and shaping the metal into tools, weapons, jewellery, etc. which created culture in the various populations that inhabited what is now China. This transition from the neolithic to the bronze age also marked the transition from prehistory to history.[5]

The Xia dynasty

According to Dr. Hammond, traditional Chinese historiography considers the Xia (Xià Cháo, 夏朝) to be the first dynasty in Chinese history.[6] The Xia however did not leave any written records, but did leave a clear demarcation to prior forms of societies before them. Interestingly enough, some scholars believe that the Erlitou civillization along the Yellow River was the sight of the original Xia dynasty.[7]

The Xia period began roughly around 2200 BCE. The Xia built palace architecture, large structures built on rammed earth platforms (compressed and firm layers of dirt), a method that would keep being used in China for the coming millennia. The Xia also saw the emergence of class society; as agriculture and pottery was creating a surplus of food, fewer farmers were needed, and a class of "non-farmers" (artisans, warriors, spiritual leaders and bureaucrats) emerged, forming the basis of Chinese class society.[6]

Dr. Hammond theorizes that this emergent class of leaders solidified their power by performing rituals for the populace. The Xia's ancestors performed totemism, a practice in which animal spirits are associated with particular tribal or clan families. In the Xia dynasty, the worship of totems of one particular family was transformed into a royal ancestral cult. In other words, not only the spirits of animals, but the spirits of the ancestors of the present day rulers came to be seen as divine powers. This further solidified the power of the royal family and laid the foundation for monarchy in Chinese society.[6]

The Xia civilisation ultimately did not leave many details as to their way of life, and most of their records came from the subsequent Shang dynasty, who shared many consistent features with the Xia.[6]

The Shang dynasty

The Shang dynasty (Shāng Cháo, 商朝), named after the royal family, begins around 1500 BCE. Dr. Hammond notes that traditional Chinese historiography uses a very elaborate and precise chronology which would place the Shang dynasty at 1766 BC, but that modern archeological investigations cannot confirm this date, and so the actual date of their foundation remains vague.[6]

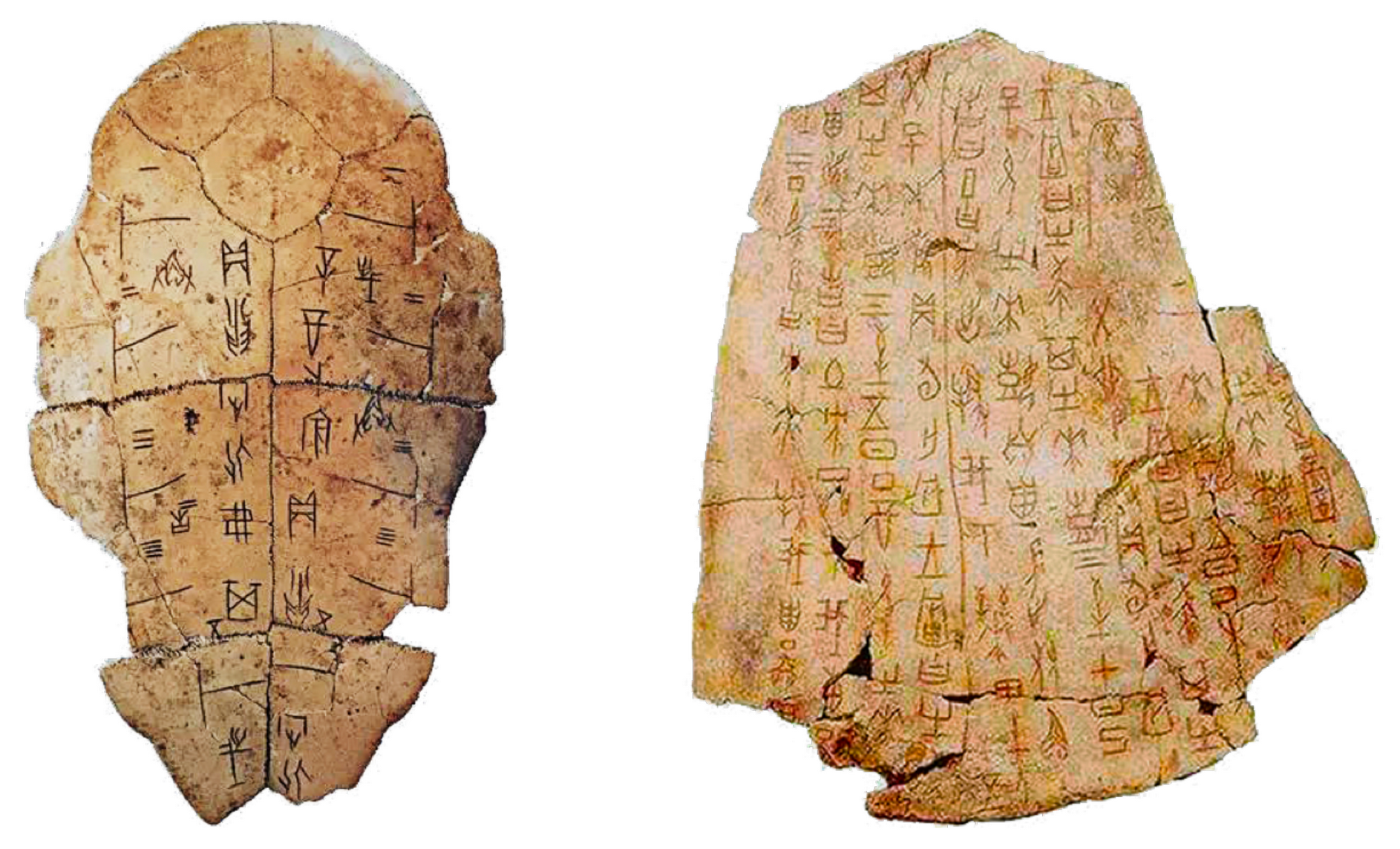

Oracle bones divination

The Shang dynasty has left many written records about their life, as they performed oracle bone divination (jiǎgǔ, 甲骨). In this practice, people would ask a question to the royal family's ancestors on either oxen shoulder blade bone or the underside of turtle shells. The question would be carved on the bone by a diviner, the class of people who could read and write. The bone would then be poked by a sharp, hot object during daily ceremonies, which caused it to crack. The way the bone cracked was then interpreted as an answer by the ancestors to the question carved into the bone. The Shang took their written records even further and kept records on the results of the divination. This means they kept record of not only the questions, but also the answers and actual outcome of the divinations.[6]

Oracle bone divination was so commonplace in the Shang period that to this day, tens of thousands of bones have been dug up.[6]

Dr. Hammond notes that these divination rituals were important to maintain the power of the dynasty and diviners, but the bronze culture was also equally important. Bronze cutlery (such as wine cups, plates or pans) were used to present offerings to the ruler's ancestors. After these offerings and sacrifices, which took place in great halls, the king would offer the "physical remains" (the offerings that had not been consumed by the ancestors) to the populace in great feasts, as a way to remind the people of his wealth and power.[6]

Succession of power

The Shang dynasty had a novel way of handling succession. In their time, life expectancy was not very long -- one could hope to live up to 30 on average. It was thus very common that the Shang king would die before his oldest son was old enough to succeed him. Because of this, the kingship passed from oldest to youngest brother. Then the eldest son of the eldest king would take over, and the process would repeat. 26 kings were recorded during the Shang period. which lasted for around 500 years (an average of one king every twenty years).[6]

The Shang also built royal capitals, which was a continuation of the Xia palace architecture on rammed earth structures. However, they didn't seem to stay in them a very long time: they had nine capitals during their 500 years rule. These buildings were bigger and more decorated than their Xia predecessors, likely as a way to display their wealth and power.[6]

Shang state

The Shang state was a federation of people. In other words, there was the Shang ruling family, their blood relations, and then people who were not blood relations to that family but were part of the Shang state. The Shang dynasty spread relatively far, and the federated people that were part of this state played a primordial role in its upkeep and border security. As such, due to the size of the Shang empire, reports, letters and communication from the king to his subordinates would be sent in writing, which characterises the Shang as a literate state.[6]

The Shang state was quite elaborate and practised division of labour from early on. Bronze objects, for example, were made with casts in which molten bronze was poured in. Their bronze industry -- mining the metal, smelting, refining, blending the metals together, the design of the objects, etc. was all organised by the Shang state and required different labourers and artisans for each step of the process. That involved the organisation of a consequent number of people as well as running activities at a number of sites (the mines, for example, were not located in the same place as the furnaces).[6]

This elaborate, organised system of production required that the Shang state had a capacity to sustain its people, e.g. feeding them, clothing them, housing them, etc. This is how archeologists know that the Shang also had an elaborate taxation system, which also appeared on oracle bones. Tributes were paid by subordinates who were part of this federation to the Shang royal family and formed the basis of taxation revenue. Furthermore, the organisation of the mining industry further established the authority of the royal family and their kin.[6]

The Shang practiced slavery, which was the first major mode of production in the world and allowed them to sustain this elaborate society and state. Slaves, as was usual in the earliest incarnation of the institution, were usually prisoners of war and criminals.[6]

Decline of the Shang period

The people not under Shang authority were a constant concern and often came up in oracle bones. Since the Shang recorded every outcome of oracle bone divination, these records show that there were frequent devastating raids from outside populations. Notably, people were recorded as being taken away as slaves during these raids.[6]

Security was a critical function of the Shang state but eventually found itself in a contradiction. The Shang dynasty needed to deploy and maintain soldiers in the border regions, where the tributary non-Shang people lived, so that they could receive their tribute and not have it stolen during raids. Over time, this created resentment from these populations, especially when security started breaking down and raids became more frequent.[6]

This unrest eventually boiled over to rebellion, when the tributary peoples to the Shang overthrew the dynasty and established the Zhou dynasty as their successors.[6]

Western Zhou

Premises

The Zhou people (Zhōu, 周), located on the western side of the Shang Empire, were a tributary community of the empire, with a mythological history of their own. Their early history involves a change from a hunting-gathering society, before developing to an agricultural society, going back to hunting and gathering, and finally settling down as more permanent farmers. According to Dr. Hammond,[5] these societal changes reflect the environmental conditions at the time (some 4000 years ago), when northwestern China was wetter, cooler, and the weather had not settled permanently, which made food sources change over time.[5]

After the Zhou settled into sedentary agricultural communities, they became affiliated as a tributary state to the Zhou, a process that left them resentful of their new lords. Around the late 12th century BCE (-1150), as the Shang dynasty was facing external raids they could not defend against, the Zhou leaders decided that the Shang were unfit to rule and they should replace them.[5]

One notable advancement of the Zhou dynasty was that they marked a break way from slavery and into early feudal society (Fēngjiàn, 封建) which worked differently from the European feudal system to which we owe the name.[5]

War against the Shang

Tai Zhou articulated this ambition which his people carried out over the the next three generations. The Zhou people followed the Wei river eastward and resettled closer to the Shang. Secondly, they sustained greater communication with other subordinated people of the Shang Empire, particulary on the west side of the Shang territory so as to create the alliances necessary to overthrow the Shang kings. Finally, around the year 1050 BC, the Zhou initiated a war against the Shang. According to Dr. Hammond, the war seems to have been initiated by Wen Zhou, referred to as a king in historical records, but his son king Wu was the one who took the throne from the Shang.[5]

While the exact date of this war has been lost, paleoastronomers have narrowed down the range of possible dates to within a few years of 1045 BCE based on the study of celestial events described at that time.[5]

On that date, the Zhou people and their allies marched to the capital of the Shang (modern day Anyang), and set themselves up on the west side of a river. On the morning of the battle, the young king Wu gave a speech calling for the overthrow of the Shang and then led his armies forward into the city. A number of ancient documents that have survived to this day describe the battle that took place on that day; the Classic of Documents contains a purported transcript of the speech king Wu gave on that day as well as a document describing the battle.[5]

The battle concluded with the killing of the Shang king; the Shang state was thus seized by the Zhou and king Wu crowned.[5]

The duke of Zhou

King Wu was still quite young when he seized the state from the Shang dynasty. King Wen had a younger brother, who is only known as the duke of Zhou in historical records, who then served as an advisor to the young king. He was seen as a very sage and moral character, as he could have easily usurped the throne from his older brother due to Wu's young age, but instead was happy to serve as an advisor.[5]

The duke of Zhou thus became a very important figure in Chinese history, even serving as a model for Confucius some 500 years later.[5]

Migration of the Shang

Although the Shang had been defeated, the Zhou did not exterminate them. The Shang were moved away from the capital of Anyang to the south and east and given a territory of their own, made into subordinates of the Zhou. They were allowed to retain their customs, including the worship of their royal family's ancestors. To this day, certain families in southeastern Anhui province trace their family all the way back to the Shang.[5]

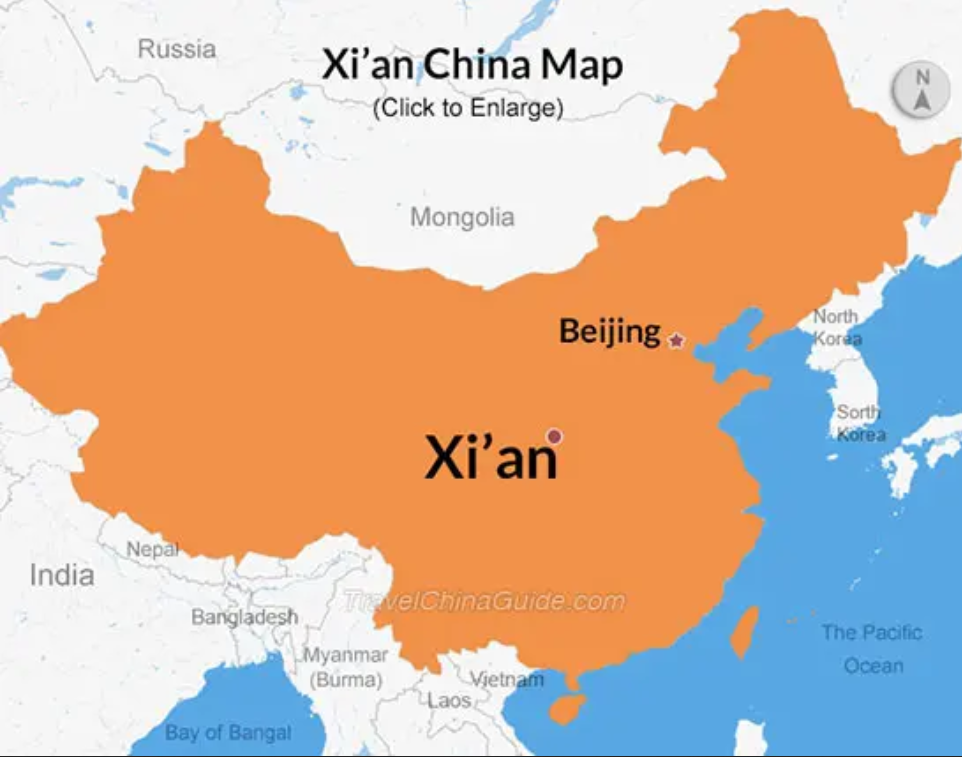

Establishment of Chang'an capital

At the same time, the Zhou moved the capital (and thus center) of their empire from Anyang back to their own ancestral homelands in the valley of the Wei river. They built a new capital at Chang'an (modern-day city of Xian), which served as a capital for a number of later dynasties.[5]

The Zhou also established a pattern for the design of capital cities which was later picked up by subsequent dynasties. Their city was designed to be the physical representation of a well-ordered world, drawing back to the Mandate of Heaven. The city of Chang'an was laid out as a square surrounded by a wall, and oriented on a north-south axis with a compound in the northern part that formed the residence of the ruler. In the southern part of the city were residential areas for the common people, markets, and other centers of activity for daily life. Surrounding the city in the four cardinal directions (north, west, south, east) were ritual complexes -- altars and other temples for the performing of sacrifices and other ceremonies.[5]

Creation of the Mandate of Heaven

To understand the Mandate of Heaven, it is important to understand what Heaven is in China. According to Dr. Hammond, the Chinese people in earlier history (including the Zhou) worshipped what we translate as Heaven (tian). Tian should not be thought of as the Christian Heaven, but rather sort of a natural operating system, the overarching mechanism that governs the functioning of everything in the universe. Tian should be understood as an all-encompassing organic system, and not as a divinity or god. However, it does have the capacity for action. One such capacity is the bestowing of the Mandate of Heaven, or the withdrawing thereof.[5]

The Zhou were the ones to develop this doctrine to justify their conquest of the Shang, arguing that there is a "proper" way for society to be organised focalised around a good ruler. since the Shang were unable to protect them from raids (and thus did not maintain the livelihood and prosperity of the people), they were unfit to rule and Heaven (tian) had withdrawn the Mandate from the Shang and given it to the Zhou.[5]

The Mandate of Heaven would become central to all political transitions from one dynasty (or form of government) to another, even enduring to this day in the People's Republic. The Mandate formed instant justification for an overthrow of a dynasty: if one succeeded in seizing the state, then they had clearly received the Mandate of Heaven. If they failed, then they clearly had not received the Mandate and thus the old dynasty would keep ruling.[5]

For the first time, the state was not the property of a ruling family but instead, drawing on earlier mythical accounts of kings Yao and Shun, considered to be something that involved the moral qualities of the rulers. The Mandate is bestowed and removed by forces outside of human control, and as such the state belongs to the dynasty that was picked by Heaven to rule.[5]

Eastern Zhou: Transition from slavery to feudalism

Early successes

The first two to three hundred years of Zhou rule were successful; that period was marked by territorial expansion (particularly in the south and southeast) and population growth. By the 8th century BCE, the Zhou state was four times larger than the territory controlled by the Shang at the time of conquest.[8]

These successes lead to new administrative challenges. Governing the entire realm from the capital became difficult as it grew due to the sheer distance to cover, and the Zhou kings started delegating power to members of the royal family: brothers, cousins, etc. were sent to these regions to fulfil administrative roles.[8] However, the Zhou soon ran out of family members to appoint and turned to military leaders, loyal to the dynasty. The practice in the Zhou kingdom was that the military commander who brought new territory to the state would be appointed its political supervisor.

In the first few reigns of Zhou kings, this system worked well. The Zhou could appoint loyal individuals and let them take care of administrating remote regions on the border of the kingdom.[8]

Administrative challenges

As time went by, the monarchy became an established institution -- not solely dependent on a moral king, but on the entire royal family. Members of the Zhou clan, who grew up in the royal capital, knew that they would be given a title to administrate eventually, and became complacent about it. At the same time, in local communities around the kingdom, the delegates managing these territories were the descendents of the original appointees, and thus they did not feel loyal to the Zhou dynasty, whose presence in these regions was almost null; they resent that they have to send taxes and tribute to the capital. This sentiment was particularly strong in the fertile southern and southeastern areas that produced a lot of food, but still had to send most of their surplus to the king as tribute.[8]

Thus these local rulers started to hold back some of the tribute they were supposed to send, while at the same time subverting the established hierarchy; records show, in fact, that at the beginning of the 8th century BCE, certain local administrators (appointed by the Zhou royal family) begin to refer to themselves as kings instead of dukes, most notably in local official documents.[8]

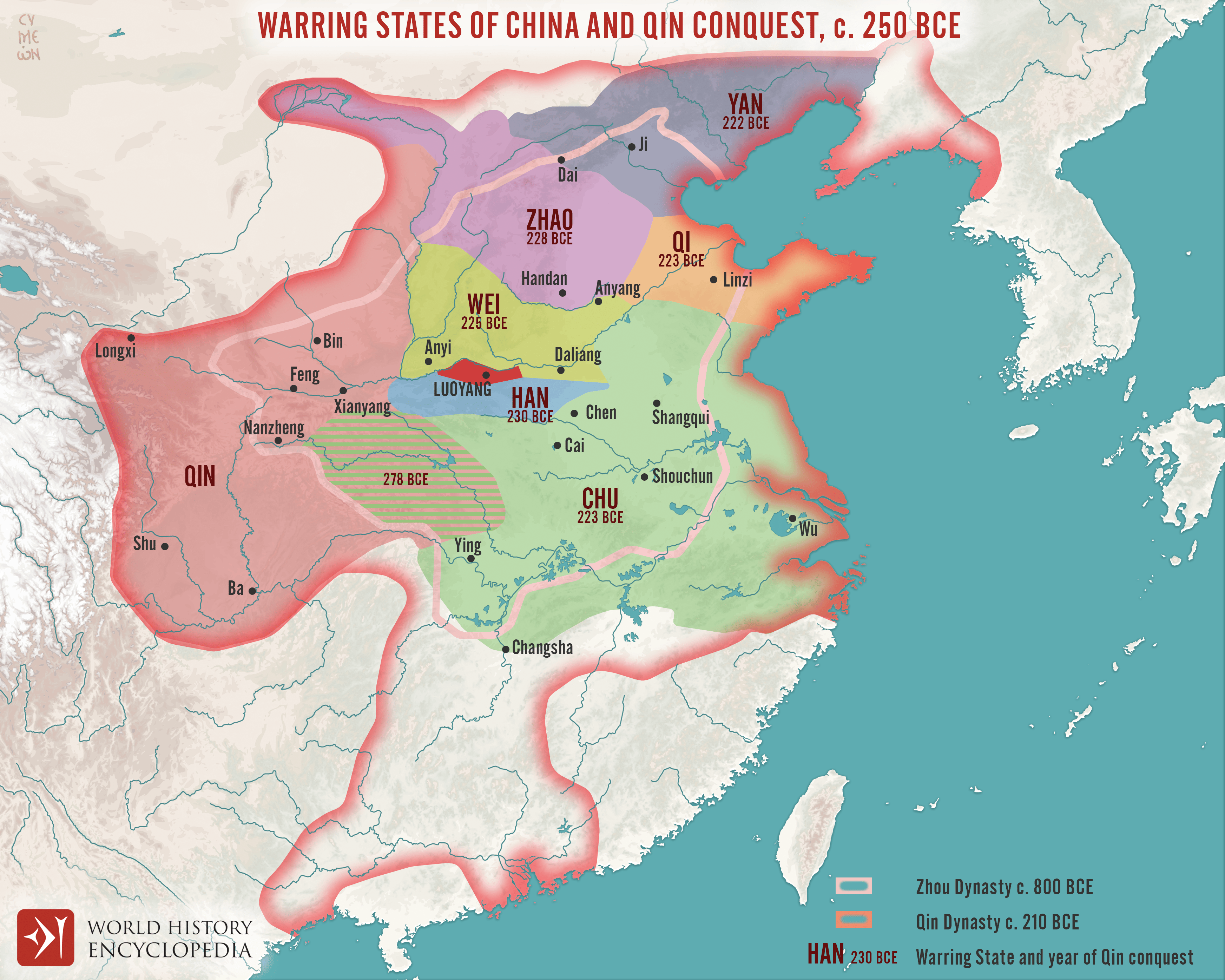

Arrival of the Qin and moving of the capital

In normal times, as the Zhou king heard of these developments, he would have sent troops to restore his authority on these tributary provinces. However, at the start of the 8th century BCE, a new people emerged from the western frontier of the Zhou kingdom, called the Qin. They started to raid into Zhou territory, which prompted them to move their capital far eastward, at the site of what is today the city of Luoyang, which remained a very important capital and cultural center for later dynasties.[8]

This move to a more secure area, which made the Zhou abandon their ancestral homeland in Chang'an. Because of this, the Zhou were unable to attend to the matter of local administrative appointees proclaiming themselves as kings, which was a challenge to the rule of the Zhou; as more local rulers proclaimed themselves king over their appointed lands, the legitimacy of the Zhou rule was called into question.[8]

The crisis took several centuries to mature: despite the challenges, the Zhou dynasty remained on the throne and ruled from Luoyang. While tributary rulers kept paying some amount of respect to the Zhou dynasty, it became clear that the Zhou did not control any territory beyond their capital.[8]

Spring and Autumn period

From the middle of the 8th century BCE to the 5th century BCE, China saw the Spring and Autumn period develop. This period gets its name from the book of the Spring and Autumn Annals, a record that described the year to year events happening in the tributary state of Lu.[8]

The rulers of Lu claimed that they were descended from the duke of Zhou, which gave them some legitimacy on the throne over other minor states vying for power. The state of Lu was also the homeland of Confucius, whom is believed to have edited the Annals.[8]

The Annals describe a process of sheer breakdown of the Zhou authority. As local rulers start calling themselves kings, so do they start acting like one: they set up royal courts in their holdings, they begin to perform rituals which are normally reserved for the king, they start to wear the clothing appropriate to a king, they demand the ritual gestures from their advisors that they themselves should show to the king, etc.[8]

Rise of the hegemons

With the breakdown of their single, unifying authority, it becomes impossible for the Zhou kings to restore order in the kingdom. Self-proclaimed kings started conquering their neighbours, and the kingdom erupted into war rapidly after that. In Chinese records, these kings are called ba wang, translated as hegemons, understood as "kings in power, but not in right". In other words, these kings were able to rule because they had the power to do so, but were not legitimate rulers as they had not received the Mandate of Heaven, still with the Zhou.[8]

This period lasted a few hundred years and saw the number of states increase in China; from a single unified state in the 8th century BCE, there were more than 250 existing by the 5th century BCE, some of them consisting only of a single town and its agricultural fields. Each of them, no matter their size, claimed to be a legitimate sovereign government. While they still acknowledged the rulership of the Zhou to some extent, this was only a performative exercise as the Zhou kings exercised no real authority outside of their domain.[8]

Hundred schools of thought

See main article: Chinese philosophy

As this breakdown process took place over China, a new class slowly emergeed: the shi (士, meaning advisor, scholar or general), a class of professional political administrators and advisors to kings and rulers. Their role was reminiscent of the diviners of the Xia and Shang period, who could read and write, but was wholly a product of the situation at the time: as the number of royal courts proliferated, there came a large demand for capable administrators and advisors. The shi travelled the land offering their services to different kings for a period of time, often creating fierce competition between kings for the most capable advisor. Often, they became a symbol of a ruler: a king who had a famous or capable advisor at his side was regarded as a good ruler.[9]

The proliferation of this class also gave rise to philosophy in China (and thus Chinese philosophy), as the shi would debate each other and, in this era of great turmoil and war, began to question the fundamental order of China and rulership to understand why the Zhou kingdom broke down, and how statesmen could avoid this fate in the future.[9]

Their influence on Chinese society was such that they survived in various ways in later dynasties, and so many of these schools of thought existed that they are today referred to as the "hundred schools of thought" (zhūzǐ bǎijiā, 諸子百家).[10]

Some of the most famous shi of this period are Confucius, Laozi, and Sun Tzu.[9]

Confucius and Confucianism

Confucius (Kong Fuzi, 孔子), was a shi and perhaps the most influential figure in Chinese philosophy. He was born in the Lu state circa 551 BCE and died in that same place around 480 BCE.[9]

Most of the information that survived about Confucius was written down by his students and their students later on, but very little is known from his contemporaries.[9]

Confucius grew up in the state of Lu and later spent a fair amount of time travelling around eastern China as a shi, offering his services to various rulers. However, Confucius was not very successful in this effort and only landed minor roles and positions as an advisor. He eventually gave up on his goal of trying to achieve political success through serving in administrations. Confucius went back to his home state of Lu and settled into the role of a teacher.[9]

The core of his ideas were about human relationships; if one wants a well-ordered society in which people can live together in peace and prosperity, then he argued people needed to realise that this happened through relationships with one another. He saw the family as a microcosm of this societal relationship: they involved on the one hand bonds of duties and obligations, and on the other bonds of affection and compassion.[9]

Five great relationships

Confucius defined a set of five great relationships, concrete examples which represented his overarching idea of all relationships in society. These are the relationship between the ruler and the subject, father and son, husband and wife, elder brother and younger brother, and finally the relationship between friend and friend. All of these relationships have certain characteristics; in each pair, one side plays a "leading" role and one plays a "following" role, even in the friend relationship: according to Confucius, there will always be a set of circumstances that puts one friend as a leader above the other (age, skill, etc).[9]

While there is a hierarchy in these relationships, they also have an aspect of reciprocity: the ruler (or father, or husband) must be a good ruler; they must fulfil their role in a proper way. If they abuse their role, then the subject (or the son, the wife, etc.) is "released from the bond of obligation. The reciprocity of these relationships is what makes them work according to Confucius, and differentiates them from a simple domineering relationship (where the ruler would just force the subject to comply to his will). If both sides are fulfilling their roles properly then, according to Confucius, society will function properly.[9]

These relationships structure society, but to make them work people need to understand this system as they encounter it so they can apply it. To make that happen, Confucius relied on ritual: he saw rituals as central to the implementation of his order of relationships in daily life. Rituals are simply repeated behaviour and can be as simple as a handshake (when two people meet, they shake hands) or as elaborate as a graduation ceremony, which involve hundreds of people.[9]

Analysis of the Zhou period

When looking back at the decline of the Zhou period, Confucius attributed its downfall to the violation of the proper ritual order: when people started taking for themselves the title of king and performing the rituals of royalty at their court, they broke with the right way of ordering society and all the wars and suffering that afflicted China since then stemmed from that fact.[9]

To fix this situation, Confucius argued for the return of the ritual order of the early Zhou rather than the chaotic disordered of the warring states period. He also advocated for the rectification of names or in other words, to "make names fit reality" (going back to the rise of the Hegemons who usurped the title of king).[9]

A critical individual in this process of rectification is what Confucius called the gentleman (jūn zǐ, 君子, literally "noble's son"). This individual is one who models the proper ritual order and behaviour in himself: he engages in learning about the past, and he seeks to approach the Dao (道, meaning "a path"), i.e. the way one should live in the world to manifest the rectification of rituals. As a role model, the gentleman can be emulated by others in society.[9]

Around 150 years after Confucius' death, a man by the name of Mencius (Meng Ke, 孟軻) picked up his work and developed Confucius' ideas further. Mencius especially turned his attention towards the relationship between a ruler and his subject, talking about the necessity of the ruler to "do the right thing", and that the people had the right to overthrow him if he failed at this duty.[9]

Daoism

Daoism (or Taoism) was theorised by Laozi (Lǎozǐ, 老子, also romanised as Lao Tsu meaning "old master") and was as important and influential as Confucianism in traditional Chinese society. While Confucianism had a very proactive outlook (society will prosper if people act towards the natural order), Daoism is radically at odds with Confucianism. It is based upon a skepticism of our knowledge and epistemology (the ability to know things).[9]

Not much is known about Laozi, and it is not sure that he even existed. His most famous work is a book that bears his name, with most subsequent writings being attributed to a later follower by the name of Zhuangzi who wrote around the 3rd century BCE.[9]

For Daoists, all knowledge is arbitrary and partial. When we think about knowledge, all we're talking about is our ability to communicate: we know something is an orange, for example, because we name it an orange; names are meaningless and made up to describe things existing in reality. Thus our knowledge, Daoists argue, is partial: it is always limited and one can never know everything.[9]

Acting on the basis of partial knowledge will lead to consequences which can't be anticipated; in trying to make things better, we often end up making them worse.[9]

Zhuangzi liked to write in fables to explain his teachings, and one such fable is of an eagle soaring high in the sky who can not discern between individual rocks and trees, it just sees patterns of colour on the ground. By contrast, a little sparrow is hopping around on the ground and sees everything up close: the individual grains in the stalks of wheat, the leaves on the trees, the gravel on the road, etc. According to Zhuangzi, neither one is right in their interpretation of what they see as they're limited by their perspective. This fable illustrates the fundamental Daoist belief of questioning one's ability to know things.[9]

Daoists were of course worried about the troubles facing China, and in fact Laozi wrote about his vision for a well-ordered society. In his opinion, an ideal life is one in which everything one should want and need is already found in one's immediate community. Thus, wanting to conquer other states does not lead one anywhere, all it does is take one out of the proper order where one really belongs. A critical concept in Daoism is wu wei (translated as "inaction") -- what it means is not to act in a way that goes against the natural flow of things or being.[9]

For Daoists, the point isn't to make the world a better place (because one cannot know all the necessary information to achieve that goal), but to live in one's own proper order.[9]

Other schools of thought

Confucianism and Daoism thus were at opposites. While the former advocated human action, the other advocated skepticism and inaction. These two schools of thought, while being the most influential in Chinese society, were not the only ones existing at the time of the warring states period however.[9]

Many of these schools were concerned with linguistics, and humankind's relationship to words in the material world. Others were concerned with military strategy, which made sense during a time of chronic wars. Sun Tzu (Sūnzǐ, 孙子) is certainly the most famous military thinkers to come out of the warring states period and was in great demand back in his time as well, unlike Confucius who had trouble finding employment as a political influencer. Other thinkers also explored cosmology or metaphysics.[9]

Two significant theories of this era, which did not survive as influential schools after the warring states period, were Mohism (Mòjiā, 墨家 named after its founder Mòzǐ, 墨子) and Legalism (Fǎ Jiā, 法家).[9]

Mohism

Mohism is remembered for two aspects of its school: the doctrine of universal love and defensive warfare.[10]

Mohists believed that one should love everyone equally and treat other people the way one would like to be treated. While there are some parallels to Confucianism (for example, Confucius' famous silver rule "do not impose on others that which you yourself do not desire"), the Mohist doctrine of universal love developed as a critical response to the Confucians' theories of reciprocal relationships, especially how some relationships were more important than other. The Mohists argued that the priority given to one's family were the vector of war as ruling dynasties were themselves a family, and thus put their family's interests above other rulers'.[10]

The Mohists, following their doctrine, also became renowned experts in defensive warfare. Their idea was that by building up the defences of smaller and weaker states (so that they could resist the attacks of stronger states), then aggression would cease to be a profitable course of action and they would stop fighting -- and instead pursue their interests by other less violent means. The Mohists offered their services as consultants to states which were at risk of being invaded, and in some cases proved to be quite effective (but obviously did not stop warfare entirely as the warring states period continued).[10]

The ideas of Mòjiā faded away as the warring states period came to an end, as they were a product of this period and ceased to be relevant in the time of peace that followed.[10]

Legalism

Legalists had an approach on politics, government and social order that was rather different from any other schools of the time. The doctrines of legalism are associated particularly with the state of Qin -- the same one that forced the Zhou to move their capital and led to their decline soon after.[10]

The Qin developed a very effective military state; the whole of their society was mobilised and directed towards the objective of expansion. These methods began to be formulated during the 4th century BCE by Shang Yang (Gōngsūn Yǎng, 公孫鞅) who was the chief minister of the Qin state at that time. His basis was quite simple, and revolved around rewards and punishments.[10]

On this basis, Shang Yang began a process that went on for over 150 years of promulgating laws, codes and regulations which gave the people in Qin society a clear understanding of what their obligations and duties were and what the consequences of failing those laws were. The idea was that by having clear laws that everybody knew and understood the consequences of breaking, then people would behave properly. The Qin proved to be truly effective in this regard, as the laws were applied equally to everyone regardless of class or status: the punishments applied to anyone who broke the law, whether they were a farmer or a general.[10]

These laws were fairly harsh; punishments often involved amputation, execution or banishment even for relatively minor offenses. In theory, the harshness was mitigated by the fact that everybody knew the punishments for breaking the law.[10]

In the 3rd century BCE, Han Fei (hán fēi, 韩非 ) developed a philosophical rationale to legalism. He himself was a shi, and had worked in a number of courts before coming to the employment of the Qin for the remainder of his life. He developed a theory of human nature, theorising that people are naturally selfish and greedy and will seek to maximise their own personal gain and minimise their pain. In theory, by exploiting this nature, it is possible to get people to do what one wanted them to do. This theory is interesting not only because it draws parallels to modern-day neoliberal arguments and justifications, but also because it broke away from other schools at the time (such as Confucianism and Mohism) who claimed there was a natural proper order to the world and people should perform their proper roles. In legalism, the state exists for the ruler: the ruler owns the state as his private property and there is no reciprocity like in Confucianism. Thus the state is not wielded as a tool to achieve the greater good, but to do what the ruler wishes.[10]

The doctrines of legalism served the Qin state very well during the warring states period, as they emerged victorious after defeating the last remaining state of Chu and unified China once again under a single dynasty.[10]

Warring states period

Around the year 480 BCE, the breakdown and fragmentation of China begins to reverse as strong states emerge and start to conquer weaker states. The number of states went from 250 to about 50-100 in just three centuries. This marked the end of the Spring and Autumn Period and the beginning of the Warring states period.[9]

End of the warring states period

Around the last decades of the period, starting at the 3rd century BCE, the Qin state collected victory over victory and quickly annexed the various remaining states, until only two were left: Qin and Chu, both controlling similarly-sized areas. The ruler of the Qin state was named Qin Shi Huangdi in Chinese historiography, meaning the first emperor of the Qin. This marked the moment the term Emperor (Huangdi) entered the Chinese vocabulary. This was a very significant act, as previous rulers were called kings (wang). Huangdi was an ancient mythological figure, from back in the age of Yao and Shun, almost a spiritual or god-like figure. The king of the Qin adopting the title of Huangdi was a claim to a type of rulership that had not been seen in China previously; it was a claim to total power over all of China, the lord of all.[10]

Qin and Han: Growth of feudal society

The title of Qin Shi Huangdi, Dr. Hammond notes, was quite ironic, as the Qin state only ruled for 14 years.[10] In that time though, they undertook dramatic transformations: controlling vast territories bigger than had been owned before by earlier dynasties.[11]

Within his kingdom, the emperor set out to create a single administrative system. His work persisted after the Qin dynasty itself collapsed and into later dynasties.[11]

The first such reform was of standardisation. When China had been divided in the Spring and Autumn and then warring states period, local circumstances had diverged quite a bit from kingdom to kingdom. For example, wagons and carts had axles of different lengths in different states. This seemingly innocuous difference force traders to switch carts at the border, as the roads were not meant for different sized carts, and while this was highly beneficial to the warring state period (as the lords could restrict and control trade more easily), it created logistical delays in the unified Qin state. The Qin axle length was standardised by Qin Shi Huangdi over the entire empire. Standard coins were also introduced in the empire, and the Qin state was the first to give Chinese coins a square hole in the middle so they could be linked on a string. Qin Shi Huangdi also standardised writing across the whole empire, normalising how characters should be written.[11]

The Qin also thought it important to establish a standard ideological system. They were not particularly attached to the ideas of Confucius or other great thinkers like Laozi: only the doctrine of legalism counted. This led, in the year 214 BCE, to a burning of books and the burying of scholars. Any books that were not teachings of legalism or practical utilitarian texts (how to do things) were destroyed. Likewise, as many teachings were taught orally by teachers and thinkers, the Qin emperor ordered that these scholars who knew the texts by heart be buried alive. This process was very thorough, and many of these texts did not survive this process, as most of them existed in only one copy at the time -- to this day, very few texts exist from before the fall of the Qin dynasty. Those that did survive were usually written down after the fall of the Qin dynasty.[11]

Overthrow of the Qin

The doctrine of legalism proved to be a very effective system at gaining power, but not at retaining it. There was no method of self-regulation in this system, i.e. no restraint on how to wield power. Qin Shi Huangdi pursued this power purely in his own self-interest and died in 210 BCE.[11] His son succeeded him on the throne, but proved unable to maintain the state his father had assembled, and he was killed only three years later.[11][11]

In the five following years, several contenders emerged, trying to establish their dynasty over China. Fairly quickly, two principal contenders appeared: Xiang Yu (Xiàng Yǔ, 项籍), and Liu Bang (Liú Bāng, 劉邦). Xiangu Yu was a general in the state of Chu prior to the unification under the Qin state, and was the most likely contender for the throne as he proved very popular in the empire.

On the other hand, hist opponent Liu Bang (who did become Emperor of China) was a relatively minor figure; he was a jailer, escorting groups of prisoners from local jails to county jails. Around the time the Qin state was collapsing, Liu Bang embarked on one of this mission, which involved an overnight journey. He made camp with his prisoners in the night and, in the morning, found that several had escaped. He knew that this would have dire consequences for him as, under the Qin system, he had failed his duties and would be likely executed. To avoid this fate, Liu Bang resorted to the only other alternative available to him: he assembled his remaining prisoners and told them he would set them free if they followed him. They became the core of his rebel army who fought against the Qin and, after the collapse of the dynasty, he continued to raise an army which eventually grew to become a serious military challenger for power.[11]

Xiang Yu and Liu Bang eventually came into direct conflict with one another. In the year 204 BCE, there was a battle in which Xiang Yu defeated his rival, inflicting very strong casualties on Liu Bang's side, after which his army (and Liu Bang's struggle for the throne) was thought to have been destroyed. However, Liu Bang had executed a strategic withdrawal which led his army into a port town on the Yellow river (named Ao). There, he seized the granary, fed his troops, recruited new followers and rebuilt his forces to resume the conflict with Xiang Yu.[11]

Two years later, Liu Bang defeated Xiang Yu in a very dramatic siege where. The story, in traditional Chinese historiography, was that Xiang Yu found his encampment surrounded by the soldiers of Liu Bang -- themselves former soldiers of the Chu -- singing folk songs of their homeland. When Xiang Yu heard the songs, he knew that his cause was lost. He had a final evening with his favourite concubine, killed her, and then leapt on his horse straight into the enemy's lines where he was finally cut down.[11]

With his main opponent taken out of the power struggle, Liu Bang was free to proclaim a new dynasty over China, which he called the Han, after the district from which he was from. The Han dynasty became one of the great ages in Chinese history, lasting for 400 years, reaching a geographical size, population and wealth never seen before. The Han dynasty was a contemporary of the Roman Empire in the west and the two indirectly traded through the silk road.[11]

The early Han dynasty

Liu Bang established the capital at Chang'an, the same city that was the first capital of the Zhou dynasty as well as the capital of the Qin empire. From there, he established a system of imperial governance which was at first a continuation of the Qin system but evolved over the next century of Han rule into a much more stable and viable order.[11]

Liu Bang inherited however two systems of governance at the time of his ascension to the throne. The administration in the western half of China was run directly from the capital: the emperor appointed officials to serve in local government for relatively short fixed terms before being sent somewhere else. This allowed the imperial court and the emperor to exercise direct control and essentially administrate these regions himself.[11]

In the eastern half of the empire, power was given to military leaders in Liu Bang's army who had secured these territories and pledged their loyalty to the new dynasty. This system had eventually led to the decline of the Zhou dynasty, and indeed became a problem as well for the Han dynasty.[11]

Nonetheless, Liu Bang was able to stabilise his rule and peacefully handed the succession to his son after his death in 195 BCE. A challenge emerged soon, however, when the family of Empress Wu sought to develop influence at court. In 180, when the next emperor came to the throne, their plan was thwarted and the Liu family was able to keep control of the throne and push aside the Wu's ambitions.[11]

By that time, the military leaders who had been given land in the eastern part of the empire were becoming restless, and a number of efforts were made by the emperors to maintain and extend their control over the east. This came to a head in 154 BCE when a rebellion took place: several of the military rulers in the east rose up and challenged the power of the Liu family. Not all of them backed the rebellion though, and the Liu family was able to manipulate these rulers in the east against one another so that they fought against each other instead of against the emperor. As those regions weakened themselves, the empire was able to bring them back into their direct administration (following the system in the west) and use them as a base for operations against the remaining rebels. Within a few years, virtually all of east China came back under the direct administration of the Han.[11]

This was a critical development: first, it indicated that the Han (and more globally the Chinese) had learned their lesson from the Zhou and how to counteract such situations. Secondly, it cemented the rulership of the Han dynasty: by 150 BCE, China was a single administrative entity, no longer divided by tributary rulers.[11]

Emperor Wudi

The immediate aftermath of this period saw one of China's most famous emperors on the throne, Wudi (Hàn Wǔdì, 汉武帝 -- Wu being his honorific title and Di coming from Huangdi, the title the Emperor of Qin established), who ruled from 141 BCE to 87 BCE -- his reign lasting for 54 years, making it the longest continuous reign in China at the time. Due to China being virtually free of internal strife and rebellion at the time of his ascension to the throne, Wudi was able to engage in many reforms that consolidated an imperial, administrative and ideological order which remained the basis of the imperial court for the next 2000 years.[11]

This process started by emperor Wudi is often called the Han synthesis by historians, and is described as a blending together of three components: Confucianism, legalism (as an administrative practice) and metaphysics.[11]

The Han legal system was inspired by the Qin system of rewards and punishments, but was made more "humane" by the inclusion of a Confucian element, which sought out to establish proper relationships between people. These two philosophies were however more concerned by the material world, and emperor Wudi was concerned with the metaphysical world as well, which he saw as an integral part (along with the material world) of a larger cosmic order.[11]

This was theorised by the likes of Dong Zhongshu (Dŏng Zhòngshū, 董仲舒) who brought together a number of ideas that had been in China for a long time already into a system that is sometimes called correlative cosmology; correlative cosmology seeks to explain correlation and connections between phenomena that can observed in the natural world and actions taking place in human society. Dr. Hammond likens it to a "doctrine of interpretation of omens": an earthquake or an eclipse, for example, may be interpreted as a sign that the natural order of things is disturbed in some way. Human misbehaviour -- including the emperor's -- would create such omens which were interpreted by the royal court to bring the emperor back on the right path.[11]

Wudi had a vision of the state that was in agreement with Confucianism as a tool for doing good, but this vision was also a rationale for his many expansions: his reign is also marked with a period of great military expansions, going as far as invading Korea in the north, Vietnam in the south and projecting power to central Asia, creating the largest Chinese empire at the time. Emperor Wudi famously apologised to the whole of China for the many wars he started near the end of his reign, which he considered a mistake.[11]

His governing style was also new; he wanted the state to proactively solve problems for people and be engaged in the economic life of the country. He was against the manipulation of the market for mercantile profiteering and created government monopolies on critical goods such as salt, iron, alcohol, etc. to regulate and dispatch these commodities around the country.[11]

Wudi also began the practice of meritocracy in the state administration, which survives in China to this day notably in the communist party's internal structure. Under this system, the royal court held examinations (based on written tests) that anyone could take to demonstrate their scholarship and learning. Passing the test would let one be appointed to positions in government. This system was initially held at a very small scale, and was not the main tool for recruiting government officials in China: during Wudi's reign, most officials came into service of the government through reputation or recommandation.[11]

Aftermath of Wudi's reign

After Wudi's death, his policies came under debate: in 81 BCE, six years after his death, great debate at court took place at the royal court, surviving in written records known as the Debate on salt and iron. Two factions formed, arguing over whether it was a good thing (in Confucian terms) for the state to intervene in the economy. One faction argued that the role of the state was to regulate private greed so the interests of the common people could be protected, and the other faction argued that the government shouldn't be intervening in society but merely create a set of moral expectations: the government itself should be good and act in a proper way, which would set the example for people in society to follow. They also argued that it was improper for the government to enrich itself by participating in private economic activity. These debates were significant in their time and were also studied by the later Chinese to set out the parameters of how interventionist or active the government should be.[11]

The result of these debates was that the government decided to abandon most of Wudi's monopolies, and allowed the economy to go its own way with a minimal amount of government intervention.[11]

This moment -- up until to around the turn of the millennium (and entrance to the Common Era) -- was characterised by a very stable period in China's history, at least for the people. During this time, the Han court became more self-centred; i.e. more concerned about its extravagant entertainments and social life. Emperors were less and less directly engaging in the affairs of administration, instead preferring to engage in leisure and leaving the management of the state to their officials. This allowed officials to become corrupt and line their own pockets. The revenue of the state was neglected, day-to-day administrative tasks were ignored, and so were military affairs. Additionally, in-law families (relatives by marriage) tried to manipulate the royal court in their favour.[11]

Later Han dynasty

This all came to a head in the year 7 of the present era when emperor Zhangdi (漢章帝) died without an heir. A brief period followed where power was usurped by Wang Mang (王莽) who headed the Xin dynasty (Xīn Cháo, 新朝, literally "new dynasty") for about 20 years. This period is known as the Wang Mang Interregnum.[12] Wang died without a successor in the year 23 of the current era, and another branch of the Liu family re-established their rule. This event started the period known as the later Han (or sometimes the eastern Han) which lasted for another 200 years.[11]

Land reforms

The Han dynasty as a whole was a period during which the land ownership underwent significant changes.[12]

Up until that point, land had been the property of lords (most of them military rulers), and the farmers that lived on the land were the possessions of the rulers as well. Most of these rulers were put in place in earlier dynasties by rewarding generals with the land they conquered, but some land grants were made to members of the political administration as rewards for services rendered.[12]

As the Han dynasty dealt with the problem of local military rulers and unified the whole empire under their sole command, their administration naturally moved to a more civilian staff and was expanded to help manage the affairs of a centralised realm. The Han then began attributing land differently, forced by the material reality of this new order in which they were the sole owner of all the land and did not rely on the loyalty of tributary lords. The practice of rewarding administrators with land became an institution under the Han.[12]

This policy also changed the make up of the agricultural economy which started resembling a market system, where individual estates owned by individual families produced grain and other commodities which were then sold over the whole of China.[12]

In theory, land remained the property of the emperor. In practice however, land that was granted out to families (and passed on from generation to generation) developed into de facto private property. The state actually started to recognize this fact and charters and other grants of land started functioning like deeds. Conflicts between landlords (such as access to water) were mediated through a legal court that recognized their property and title as land owners.[12]

The advent of private property was a very significant event in the history of China, and would survive for millennia after that. Generational wealth began being amassed in a process which could be likened to primitive accumulation.[12]

Cultural shift

Given that the base changed, so did the superstructure of China. Chinese culture had, prior to the later Han, been focused primarily on tales of heroism and the glories of warfare, which were characteristic of the warring states period. The Han instead pursued cultural sophistication: learning and the pursuit of knowledge, being able to both read and write poetry, writing essays, became more culturally significant and valued in the later Han. This shift was spearheaded by the ruling class and mostly concerned them.[12]

End of the Han period

Eunuch influence

Internal conflicts start reappearing at the royal court however, with in-laws trying to seize power at court, military leaders resenting this new class of landlords who, they feel, have stolen their titles, and eunuchs becoming a problem as well. Eunuchs were somewhat unique to Chinese society: they were castrated males who served in the private residential parts of the imperial palace. Their condition made them non-threatening to the line of succession, and while eunuchs were not unique to China per se, their specific role in imperial China was. Eunuchs also worked with the emperor's concubines, and in China non-eunuch males were not allowed to enter the residential part of the palace. Most of the time, eunuchs kept to their menial role but in times when the succession led to a young emperor on the throne, eunuchs could be influential over the young emperor who likely had one as his tutor or companion.[12]

Decline of the Han

Eunuchs gaining influence notably became a problem in the later Han when a series of young emperors came to the throne, which turned them into a major faction within the imperial court.[12]

Making matters worse, the weakening of imperial oversight allowed local strongmen -- not yet military figures, but mostly private land owners -- to intensify their exploitation over the peasantry, raising taxes and rents, creating discontent. Unsurprisingly, this situation led to the outbreak of rebellions against landlords and the dynasty over large parts of China. The empire responded by leading military interventions to quell these rebellions which, in a domino effect, increased the power of the military.[12]

By the latter part of the second century, the Han dynasty had ceased to be a functional political entity. Much like the later Zhou, it still existed and emperors succeeded one another on the throne, but real power dissolved and strongmen in the country expanded their territory as factionalism at court weakened the functioning of the state even further.[12]

Eventually, in the year 220, the last Han emperor was set aside and the country broke up into three successor states, one of which was ruled by a member of the Liu family (the ruling family of the Han dynasty), named Liu Bei (Liú Bèi, 刘备).[12]

The three kingdoms period

The breakup of the Han state led to the very short period (lasting from 220 to 265) known as the three kingdoms (Sānguózhì yǎnyì, 三国志演义), titled after the Chronicles of the Three Kingdoms (sānguó zhì, 三国志) written by Chen Shou (Chén Shòu, 陈寿) who lived through the period as a military officer of the Shu kingdom.[12]

The three kingdoms in question were:

- Shu (蜀), in modern-day Sichuan province, ruled by Liu Bei of the Han dynasty.[12]

- Wei (魏), situated in the north, ruled by Cao Pi (曹丕), son of Cao Cao (Cáo Cāo, 曹操), a famous general of the late Han empire.[12]

- Wu (吳), in the southeast, ruled by Sun Quan (Sūn Quán, 孙权).[12]

Beginning of the period

The three kingdoms period started in the same way the earlier breakdown of the Zhou had, by a fragmentation of the empire into various sovereign states. However, unlike the breakdown of the Zhou era, the three kingdoms remained stable among themselves and did not divide themselves. They all presented themselves as Confucian regimes: all three employed a Confucian administration and were concerned with doing good in their own states. Thus, there was still a continuity from the Han period -- with the distinction that the heroes of this era are generals and not scholars.[12]

Significance of the three kingdoms period

It remains to this day one of the most famous eras in Chinese history due to the age it represents; unlike most periods of Chinese history, the heroes of the three kingdoms are not the kind of heroes portrayed in earlier times for their strength and might, but remembered their cleverness and wit. Deceiving your enemy, i.e. winning a fight by not fighting, are considered the great talents of this era. Cao Cao and Zhuge Liang (Zhūgě Liàng, 诸葛亮) are considered the two most exemplar heroes of this period.[12]

In one instance, Dr. Hammond notes, a general had brought his army to the south, setting up camp on the bank of a large river. On the other side of the river were the enemy's forces. Their supply lines extended and arriving from a long march, the army in the north was in a tough spot for the coming battle. If they could inflict a decisive victory on their enemy at that time, however, they would certainly turn the tide of war. To make matters worse, the incoming army from the north had used up almost all their arrows in the battles on the way to the river. They thus decided to take advantage of the local conditions: in the evenings, a fog would come down on the river due to meteorological conditions at that time of year. Going upstream, they commandeered boats from the locals. In the boats, they built mannequins out of straw and put their uniforms on these strawmen. In the evening, they pushed these boats full of straw puppets down the river. The sentries of the opposing army suddenly saw several boats coming down the river, full of soldiers lined up to attack. They unleashed their arrows on the boats, hitting only the strawmen. Further downstream, the first army then brought the boats to shore and collected the arrows from the boats, resupplying themselves. Dr. Hammond notes this story is significant because it has been passed down for millennia, and remains told to this day. These stories have been dramatised into poetry, operas, novels and, more recently, TV shows in China.[12]

The Three Kingdoms period was immortalised and made famous by the epic novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sānguó Yǎnyì, 三国演义) written in the 14th century by Luo Guanzhong (Luó Guànzhōng, 湖海散人). The novel is considered one of the four great classics of Chinese literature.[12]

End of the period

In 265 CE, in the state of Wei, the Sima family seized power from the Cao family. They fielded a force which conquered the states of Wu and Shu, and from that time until the year 304, their dynasty of the Jin replaced the three Kingdoms and united China again.[12]

That period of unification did not last very long however, as other events in Asia (which, Dr. Hammond notes, are still not fully understood) brought about a great migration of people around this time down into northern India. At the beginning of the 4th century, Turkic speaking people started moving into northwestern China.[12]

Buddhism in China

See main article: Buddhism

Chinese history and culture is very largely self-contained, and so the arrival of Buddhism marked one of the rare moments when an outside element came into China.[13]

Origins of Buddhism

Buddhism traces its origins to India, at around the 6th century BCE -- the same time the teachings of the hundred schools are appearing in China. Dr. Hammond notes that this is a chronological coincidence which coincides with the appearance of other great ages of philosophy elsewhere in the world (such as in Ancient Greece or Persia).[13]

There are plenty and very specific accounts around the origins of Buddhism -- stories about the life of Siddhartha Gautama, the first Buddha and founder of Buddhism -- but many contradict each other in certain aspects, which makes establishing a historical timeline of the Buddha's early life difficult.[13]

The common thread to the origin of Buddhism is as follows: Siddhartha Gautama (also referred to as Shakyamuni, the light of the Shakyas, his clan) underwent several life-changing experiences, and as a result of those became a teacher of new ideas which took root in India, developed and grew there, and eventually spread to the rest of South and Southeast Asia.[13]

He came from a noble family in northern India (now in Nepal). As a noble, he grew up in conditions of great luxury and comfort. He was raised in a palace, and isolated in many ways from the realities of life around him. For the young prince, life was beautiful and a good thing to live.[13]

At a certain point, he came to a realisation that not everything in the world is perfect and beautiful. In one account, the prince was out in the palace gardens one day, when he heard a sound he did not recognize. He climbed a tree near the wall of the garden, looking out onto the town street. There, he saw a procession of people going by carrying a plan with something wrapped in cloth and adorned with flowers. Not understanding what he was seeing, the prince went to his parents to ask them about this strange event. They explain to him that he saw a funeral procession; the wrapped up object was a dead body, and the sound he heard was the sound of crying and lamentation. This was the first encounter the prince had with death and the suffering associated with it; thus awakening him for the first time to the imperfections of the world.[13]

There are a number of other accounts, but the common link between them is that at some point, before becoming the Buddha, Gautama saw or experienced something which made him understand imperfection in his previously perfect sheltered life.[13]

The prince then went out in search of understanding, to understand why there is suffering and imperfection in the world. He ran away from the palace and embarked on a spiritual quest which took him around the whole of northern India. This geographical area, Dr. Hammond notes, was very spiritually rich at the time: hermits were common in the woods, marketplaces were full of preachers, and the prince spent a number of years going from one teacher to another asking his question: "why is there suffering, and is there anything we can do about it?"[13]

None of the teachers he encountered, however, gave the prince satisfactory answers. Eventually, he found a place called Sarnath (near the modern-day city of Varanasi, India). There, he went into a "deer park" -- likely an estate belonging to a family connected to his. While sitting under a tree, he suddenly had a moment of enlightenment and understood the answer to his question. Immediately following this event, the prince gave his first teachings. Following that event, he kept travelling and attracting more followers until the moment he realised he was soon going to depart the material world. Several accounts exist of what happened next; in one account, the Buddha bodily ascended to the celestial realm. In others, he left his physical body behind and spiritually transformed -- in those schools, there are relics of the Buddha's body.[13]

After his death or departure, the Buddha's followers took up the role of becoming his interpreters and teachers of their own. It was from that point forward that Buddhism grew and developed a religious practice and institution.[13]

Teachings of Buddhism

In essence, the principles of Buddhism are very straight-forward. The key is the realisation of the nature of suffering; suffering is a part of our natural lives, and arises from our attachment to things in the material world. To be free of suffering, one has to free themselves from their attachments to the world around them. This can happen through meditation, renunciation and other spiritual undertakings.[13]

These are the four noble truths and are the core to all schools of Buddhism.[13]

The reason attachment is the source of suffering is that the reality of the world is impermanent: everything that exists passes away at some point; it has a beginning and an end. The appearance of permanence is an illusion (maya in Sanskrit). Illusion doesn't mean that things do not actually exist, but that nothing is going to permanently, continuously exist forever.[13]

The most central experience of attachment is our own selves; we are all attached to ourselves (and our lives). The idea of rejecting attachment is very straightforward in theory, but becomes understandably difficult to put into practice: it is almost impossible to detach oneself from their own life. This is why the spiritual practice of renunciation (through meditation and other practices) becomes very important to Buddhists.[13]

Schools of Buddhism

In the centuries after the death of the Buddha, his teachings develop and eventually spread, and two major schools of Buddhism arise.[13]

Theravada school

Theravada Buddhism is primarily focused on the attainment of individual spiritual liberation; it takes the teachings of the Buddha at their most basic level and is concerned with how each individual can attain enlightenment for themselves.[13]

Early Theravada Buddhism sees the earliest development of monasticism (choosing to live in a monastery) as individuals renounce their involvement in society and leave behind the things which attach them to this world, including the very strong attachment to family and friends.[13]

At first, Theravada Buddhists simply retreated from the world and became hermits or wanderers. But as time went by, groups came together not to form a society with formal rules and practices, but rather into "places of dwelling", places where they would usually gather together.[13]

Mahayana Buddhism

About 300 years later, a second school of Buddhism began to emerge, called Mahayana (great vehicle). This school moved its focus away from individual spiritual liberation and towards the salvation of all sentient beings. In this school of thought, any being capable of consciousness will be conscious of its own mortality and of the world around it. Therefore, it will be subject to the suffering caused by attachment. Mahayana Buddhism believes that one can't be truly spiritually free so long as they know others continue to suffer.[13]

Mahayana Buddhism introduced the concept of the Bodhisattva, a being who has reached a point of spiritual liberation: they could attain a state of transcendence as they have reached their individual liberation, but choose to remain in the material world to help other beings along the path of spiritual enlightenment.[13]

Spreading of Buddhism to Asia

The spread of Mahayana Buddhism was linked in part to the embrace of Buddhism by king Ashoka in India. He ruled much of northern India and wanted to be a good king; he held spiritual debates at his court and decided that Buddhism was the best answer to the problems facing people. He erected pillars of stone to proclaim and promote the teachings of Buddhism around his realm, specifically Mahayana.[13]

It was from his kingdom that Buddhism spread out beyond India and into the rest of south and southeast Asia. The school that reached these places was Theravada. Mahayana Buddhism tended to go north and west and into central Asia, picked up along the silk road: Buddhist monks traveled along the silk road, spreading their teachings.[13]

Arrival of Buddhism in China

It was from this route that Buddhism arrived in China some time in the second half of the Han dynasty. When Buddhist monks arrived in China, they were welcomed at the court of the emperor: the Han emperor himself was a spiritual figure himself, dating back to the Shang dynasty and the worship of his ancestors. In that role, he was a patron to all kinds of spiritual practices.[13]

When Buddhist monks arrived at Luoyang, they were given room and board and allowed to practice. But, at the beginning, they were considered more of an exotic curiosity; they were foreigners coming from outside of China, and their teachings were interesting, but different.[13]

Eventually, as the Han state deteriorated into widespread misery and rebellions, Buddhism became more popular among the masses; this should not be surprising, as it was a time of suffering and as such a philosophy that addressed the origins of suffering and offered a path out of it proved popular. Buddhism rapidly took root in China from that point on and became a part of Chinese culture and society. The teachings were spread through texts brought from India and by the oral teachings of monks. In the late second century and into the third century CE, Buddhism became a popular religion in China (popular in that it was the religion of the people).[13]

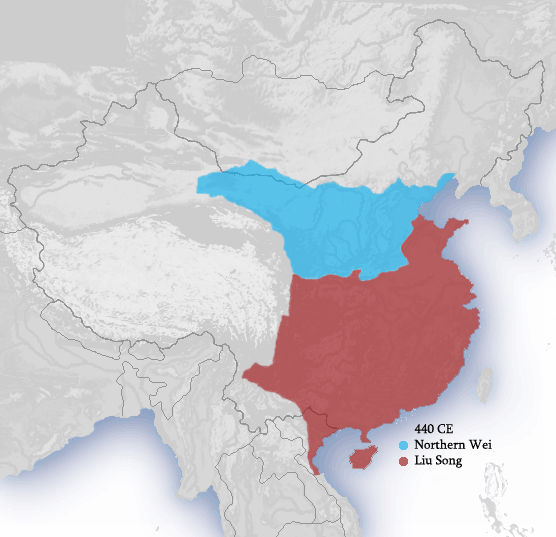

Great migration to China

After the short-lived Jin dynasty, and as Buddhism was spreading into China, a new force came into China from outside: a great migration of peoples from Central Asia moved into the Chinese heartland. This event was part of a larger series of migrations that took place all over Asia during the fourth century, but historians are not sure why that movement happened.[14]

This period is called the northern and southern dynasties (Nán-Běi Cháo, 南北朝) in Chinese historiography, with the new conquerors forming the northern dynasties, and the Han people pushed south forming the southern dynasties.[14]

The people that came to northern-northwestern China (relative to the borders at the end of the Han dynasty) spoke a language that is an ancestor to Turkish, and are sometimes called proto-Turkic by historians. They arrived in a space occupied by the Xiongnu people, who had been a constant presence and, at times, either a welcome trading partner or a threat on the Chinese frontier -- the Han dynasty build the Great Wall to defend against their raids.[14]

When the Turkic peoples started migrating into the territory of the Xiongnu, who were nomadic, they became displaced and moved further up north. After a long migration that took them several decades, they emerged in European history as the Huns.[14]

Eventually, these Turkic peoples moved from what was the Xiongnu territory and into China as well, which was a fertile area. Their migration came to an end north of the Yangtze river, which they did not cross. The north of China at the time was home to 20-30 million people, and the migratory populations totalled fewer than a million people. It should be understood that this process of migration was not peaceful and did not displace the Chinese people established there, but rather these newcomers established themselves as sort of overlords.[14] In this process, they displaced the empire of China from the region and instead established their rule, taking over by force. This period is called the Northern dynasty.[14]

South of the Yangtze river, Chinese civilisation and political order was preserved. However, Chinese presence in that area had only been established for a few hundred years at most; Dr. Hammond notes that the Chinese population in the south was aware that they were not living in their ancestral homeland.[14]

Northern Wei dynasty

This process of migration only ended in the early 5th century, with many groups coming in at different times and establishing their rule of different areas. The most historically significant of these dynasties is the Wei dynasty (Bei Wei 北魏) -- not to be confused with the Wei kingdom from the three kingdoms period (魏). To differentiate the two, historians often call it the Northern Wei dynasty or the Tuoba kingdom (拓跋魏), named after its people.[14]

This dynasty controlled major parts of the modern-day Henan, Hebei and Shanxi provinces. They first established their capital near the modern-day city of Datong, and after a hundred years or so moved it to the historical capital of Luoyang.[14]

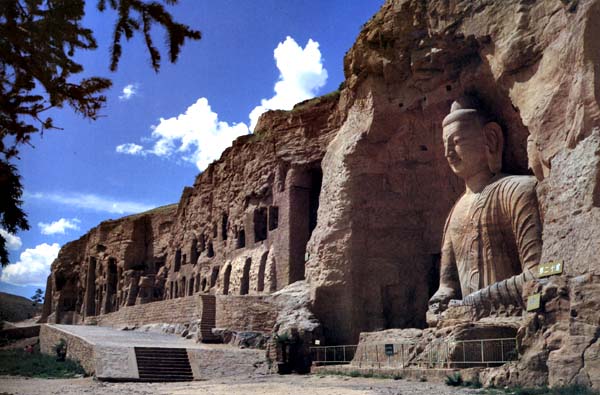

Cave temples