More languages

More actions

mNo edit summary Tag: Visual edit |

(Added links, fixed a typo, and added to the infobox) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox country|name=Republic of Ghana|native_name=Gaana Adehyeman|image_flag=Flag of Ghana.png|capital=Accra|largest_city=Accra|flag_caption=[[Flag of Ghana|Flag]]|image_map=Map of Ghana.png|image_map_size=200|official_languages=English|area_km2=238,535|population_estimate=32,103,042|population_estimate_year=2022}} | {{Infobox country|name=Republic of Ghana|native_name=Gaana Adehyeman|image_flag=Flag of Ghana.png|image_coat=Coat of arms of Ghana.png|capital=[[Accra]]|largest_city=Accra|common_name=Ghana|flag_caption=[[Flag of Ghana|Flag]]|motto="Freedom and Justice"|national_anthem="God Bless Our Homeland Ghana"|image_map=Map of Ghana.png|image_map_size=200|official_languages=English|area_km2=238,535|population_estimate=32,103,042|population_estimate_year=2022}} | ||

'''Ghana''', officially the '''Republic of Ghana''', is a | '''Ghana''', officially the '''Republic of Ghana''', is a [[Capitalism|capitalist]] state in [[West Africa]] which borders [[Republic of Côte d'Ivoire|Ivory Coast]], [[Burkina Faso]], and [[Burkina Faso|Togo]]. It was established in 1960, following the dissolution of the [[Dominion of Ghana]] by [[Kwame Nkrumah]]. Following the [[United States of America|US]] backed overthrow of Kwame Nkrumah's government in '66, the country was plagued by a series of military regimes and [[neocolonialism]]. [[Bourgeois democracy|Liberal democracy]] would eventually be established in 1993 by former dictator [[Jerry Rawlings]]. Ghana currently stands as a two-party state in which political power is monopolized by the [[New Patriotic Party]] liberals and the [[National Democratic Congress]] social democrats. | ||

Ghana is | |||

==History== | ==History== | ||

===Early history=== | ===Early history=== | ||

Archaeological evidence indicates that present-day Ghana has been inhabited for many thousand years. The early Kingdom of Ghana (sometimes known as "Ghanata" or "Wagadugu") was one of the most powerful African empires for several hundred years.<ref name=":0">[https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/history/timeline.php "History Timeline- Chronology of Important Events."] West Africa, Early History. GhanaWeb. [https://web.archive.org/web/20230313103743/https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/history/timeline.php Archived] 2023-03-13.</ref> | Archaeological evidence indicates that present-day Ghana has been inhabited for many thousand years. The early Kingdom of Ghana (sometimes known as "Ghanata" or "Wagadugu") was one of the most powerful [[Africa|African]] empires for several hundred years.<ref name=":0">[https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/history/timeline.php "History Timeline- Chronology of Important Events."] West Africa, Early History. GhanaWeb. [https://web.archive.org/web/20230313103743/https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/history/timeline.php Archived] 2023-03-13.</ref> | ||

===European arrivals=== | ===European arrivals=== | ||

In 1471, the [[Portuguese Republic|Portuguese]] arrived on the coast of Guinea. Over time, more [[Europe|Europeans]] arrived in Ghana, attracted by gold, ivory and timber. Eventually, [[Slavery|enslaved]] Africans for plantations in the [[America|Americas]] became the focus of trade, and European powers such as [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland|England]], the [[Kingdom of the Netherlands|Netherlands]], Portugal, [[Federal Republic of Germany|Germany]], [[French Republic|France]], [[Kingdom of Sweden|Sweden]] and [[Kingdom of Denmark|Denmark]] all competed in the slave trade for over 300 years. The Europeans traded weapons and manufactured goods for enslaved Africans, who were transported for across the Atlantic Ocean to work on plantations, in a system commonly referred to as the [[Atlantic slave trade]].<ref name=":0" /> | In 1471, the [[Portuguese Republic|Portuguese]] arrived on the coast of [[Republic of Guinea|Guinea]]. Over time, more [[Europe|Europeans]] arrived in Ghana, attracted by gold, ivory and timber. Eventually, [[Slavery|enslaved]] Africans for plantations in the [[America|Americas]] became the focus of trade, and [[Europe|European]] powers such as [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland|England]], the [[Kingdom of the Netherlands|Netherlands]], Portugal, [[Federal Republic of Germany|Germany]], [[French Republic|France]], [[Kingdom of Sweden|Sweden]] and [[Kingdom of Denmark|Denmark]] all competed in the slave trade for over 300 years. The Europeans traded weapons and manufactured goods for enslaved Africans, who were transported for across the Atlantic Ocean to work on plantations, in a system commonly referred to as the [[Atlantic slave trade]].<ref name=":0" /> | ||

=== British colony=== | === British colony=== | ||

From 1821 until its independence in 1957, Ghana fell under British rule and was known as the [[Gold Coast]]. The Gold Coast was officially proclaimed a British crown colony in 1874. By this time, slavery had become illegal under British law, and so business in colonial Ghana focused more on exploiting cocoa, gold, timber and palm oil. | From 1821 until its independence in 1957, Ghana fell under British rule and was known as the [[Gold Coast]]. The Gold Coast was officially proclaimed a British crown colony in 1874. By this time, slavery had become illegal under British law, and so business in colonial Ghana focused more on exploiting cocoa, gold, timber and palm oil. | ||

In 1947, [[J.B. Danquah]], the president of the [[United Gold Coast Convention]] (UGCC), the Gold Coast's first opposition political party, invited [[Kwame Nkrumah]] to become the party's Secretary General.<ref name=":4">[https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/ghanaians-campaign-independence-british-rule-1949-1951 “Ghanaians Campaign for Independence from British Rule, 1949-1951 | Global Nonviolent Action Database.”] Swarthmore.edu. [https://web.archive.org/web/20230301145450/https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/ghanaians-campaign-independence-british-rule-1949-1951 Archived] 2023-03-19.</ref> Nkrumah was a proponent of [[Socialism|socialist]], [[Anti-imperialism|anti-imperialist]] and [[Pan-Africanism|Pan-Africanist]] ideas and had been abroad studying economics, sociology, theology, education and philosophy, in addition to organizing abroad for several years such as having a role in convening the [[Fifth Pan-African Congress]] in 1945.<ref name=":5">Abayomi Azikiwe. [https://www.workers.org/2009/world/nkrumah_1008/ “Nkrumah and Ghana’s Independence Struggle.”] Workers.org. [https://web.archive.org/web/20211126025113/https://www.workers.org/2009/world/nkrumah_1008/ Archived] 2021-11-26.</ref> | In 1947, [[J.B. Danquah]], the president of the [[United Gold Coast Convention]] (UGCC), the Gold Coast's first opposition political party, invited [[Kwame Nkrumah]] to become the party's Secretary General.<ref name=":4">[https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/ghanaians-campaign-independence-british-rule-1949-1951 “Ghanaians Campaign for Independence from British Rule, 1949-1951 | Global Nonviolent Action Database.”] Swarthmore.edu. [https://web.archive.org/web/20230301145450/https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/ghanaians-campaign-independence-british-rule-1949-1951 Archived] 2023-03-19.</ref> Nkrumah was a proponent of [[Socialism|socialist]], [[Anti-imperialism|anti-imperialist]] and [[Pan-Africanism|Pan-Africanist]] ideas and had been abroad studying [[economics]], [[sociology]], [[theology]], [[education]] and [[philosophy]], in addition to organizing abroad for several years such as having a role in convening the [[Fifth Pan-African Congress]] in 1945.<ref name=":5">Abayomi Azikiwe. [https://www.workers.org/2009/world/nkrumah_1008/ “Nkrumah and Ghana’s Independence Struggle.”] Workers.org. [https://web.archive.org/web/20211126025113/https://www.workers.org/2009/world/nkrumah_1008/ Archived] 2021-11-26.</ref> | ||

In February 1948, a group of unarmed ex-servicemen who had fought with the Gold Coast Regiment of the Royal West African Frontier Force in the [[Second World War]] set out on a march from Accra to the suburban residence of the British governor to present him with a petition of grievances. When they were ordered to stop, they refused, and the colonial police opened fire, killing three of the ex-servicemen. Angered by this unwarranted violence and the continued injustices suffered by the population in general, people in Accra took to the streets, and rioting spread throughout other towns and cities. This eventually resulted in 29 deaths and hundreds of other casualties after five days of rioting. On 12th March the governor ordered the arrest of "The Big Six," leading members of the UGCC, which included Kwame Nkrumah. The governor believed they were responsible for orchestrating the disturbances. They were detained but released a month later.<ref>KESSE. [https://ghanaianmuseum.com/the-1948-riots-which-triggered-ghanas-independence/ “1948 Riots Which Triggered Ghana’s Independence.”] Ghanaian Museum. February 28, 2022. [https://web.archive.org/web/20230319121951/https://ghanaianmuseum.com/the-1948-riots-which-triggered-ghanas-independence/ Archived] 2023-03-19.</ref> | In February 1948, a group of unarmed ex-servicemen who had fought with the Gold Coast Regiment of the [[Royal West African Frontier Force]] in the [[Second World War]] set out on a march from [[Accra]] to the suburban residence of the British governor to present him with a petition of grievances. When they were ordered to stop, they refused, and the colonial [[police]] opened fire, killing three of the ex-servicemen. Angered by this unwarranted violence and the continued injustices suffered by the population in general, people in Accra took to the streets, and rioting spread throughout other towns and cities. This eventually resulted in 29 deaths and hundreds of other casualties after five days of rioting. On 12th March the governor ordered the arrest of "[[The Big Six]]," leading members of the UGCC, which included Kwame Nkrumah. The governor believed they were responsible for orchestrating the disturbances. They were detained but released a month later.<ref>KESSE. [https://ghanaianmuseum.com/the-1948-riots-which-triggered-ghanas-independence/ “1948 Riots Which Triggered Ghana’s Independence.”] Ghanaian Museum. February 28, 2022. [https://web.archive.org/web/20230319121951/https://ghanaianmuseum.com/the-1948-riots-which-triggered-ghanas-independence/ Archived] 2023-03-19.</ref> | ||

During this time, Nkrumah was among those advocating for immediate political independence for the Gold Coast, while others of the UGCC were advocating for a more gradual approach to independence.<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":5" /> | During this time, Nkrumah was among those advocating for immediate political independence for the Gold Coast, while others of the UGCC were advocating for a more gradual approach to independence.<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":5" /> | ||

Eventually, Nkrumah formed the [[Convention People's Party]] (CPP), advocating for "self-government now", which achieved rapid success and quickly became a major player on the nationalist political scene. | Eventually, Nkrumah formed the [[Convention People's Party]] (CPP), advocating for "self-government now", which achieved rapid success and quickly became a major player on the [[Nationalism|nationalist]] political scene. | ||

As the British colonial government continued to refuse to accept the popular demands of the people for self-government, Nkrumah called for a [[Positive Action]] campaign in 1950, a series of protests and strikes and a boycott of European goods, intended to fight colonialism through nonviolence and education.<ref>KESSE. [https://ghanaianmuseum.com/positive-action-campaign-declared-by-nkrumah/ “Positive Action Campaign Declared by Nkrumah.”] Ghanaian Museum. January 8, 2022. [https://web.archive.org/web/20221129071953/https://ghanaianmuseum.com/positive-action-campaign-declared-by-nkrumah/ Archived] 2022-11-29.</ref> In response to this, Nkrumah and other leaders were arrested and imprisoned. However, Nkrumah was released from jail after the CPP won the first election for the Legislative Assembly. | As the British colonial government continued to refuse to accept the popular demands of the people for self-government, Nkrumah called for a [[Positive Action]] campaign in 1950, a series of protests and [[Strike action|strikes]] and a boycott of European goods, intended to fight [[colonialism]] through nonviolence and education.<ref>KESSE. [https://ghanaianmuseum.com/positive-action-campaign-declared-by-nkrumah/ “Positive Action Campaign Declared by Nkrumah.”] Ghanaian Museum. January 8, 2022. [https://web.archive.org/web/20221129071953/https://ghanaianmuseum.com/positive-action-campaign-declared-by-nkrumah/ Archived] 2022-11-29.</ref> In response to this, Nkrumah and other leaders were arrested and imprisoned. However, Nkrumah was released from jail after the CPP won the first election for the Legislative Assembly. | ||

Nkrumah became Prime Minister in 1952, was re-elected in 1954 and 1956, and retained the position when Ghana declared independence from Britain in 1957.<ref name=":0" /> | Nkrumah became Prime Minister in 1952, was re-elected in 1954 and 1956, and retained the position when Ghana declared independence from Britain in 1957.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

===Independence === | ===Independence === | ||

Ghana became independent from the | Ghana became independent from the United Kingdom in 1957, under Kwame Nkrumah's administration. Nkrumah's administration was socialist and Pan-Africanist in its leanings. A 1966 U.S. government internal memorandum describes Nkrumah as "strongly pro-Communist" and says that "Nkrumah was doing more to undermine our interests than any other black African."<ref name=":1">Komer, Robert W. [https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v24/d260 "Memorandum From the President’s Acting Special Assistant for National Security Affairs (Komer) to President Johnson."] Johnson Library, National Security File, Memos to the President. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume XXIV, Africa. Document #260. Office of the Historian. United States Department of State. [https://web.archive.org/web/20220518133259/https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v24/d260 Archived] 2022-05-18.</ref> | ||

Nkrumah provided funding and training to members of the [[African National Congress]] in [[Republic of South Africa|South Africa]] who wanted to overthrow [[apartheid]]. | Nkrumah provided funding and training to members of the [[African National Congress]] in [[Republic of South Africa|South Africa]] who wanted to overthrow [[apartheid]]. | ||

Economically, independent Ghana was developed through Five Year Plans, including the First and Second Five Year Development Plans (1951-1956 and 1959-1964), as well as an uncompleted Seven Year Development Plan beginning in 1964, which was halted after an imperialist-backed reactionary coup regime took power in 1966. The Seven Year Development plan as well as the coup are described in detail in Nkrumah's 1968 book, ''[[Kwame Nkrumah#Dark Days in Ghana (1968)|Dark Days in Ghana]]''. | Economically, independent Ghana was developed through [[Five-year plans of Ghana|Five Year Plans]], including the First and Second Five Year Development Plans (1951-1956 and 1959-1964), as well as an uncompleted Seven Year Development Plan beginning in 1964, which was halted after an imperialist-backed [[reactionary]] [[Coup d'état|coup]] regime took power in 1966. The Seven Year Development plan as well as the coup are described in detail in Nkrumah's 1968 book, ''[[Kwame Nkrumah#Dark Days in Ghana (1968)|Dark Days in Ghana]]''. | ||

===1966 coup d' | ===1966 coup d'état=== | ||

The [[CIA]] organized a coup against Nkrumah on 24 February 1966. At least 1,600 people died in the coup, which was also supported by [[Canada]] and the United Kingdom. The National Liberation Council (NLC) that took power after the coup privatized state-owned businesses. The [[International Monetary Fund|IMF]] convinced the military junta to end Ghana’s industrialization program.<ref>{{Web citation|author=Charles Quist-Adade|newspaper=[[CovertAction Magazine]]|title=How Did a Fateful CIA Coup—Executed 55 Years Ago this February 24—Doom Much of Sub-Saharan Africa?|date=2021-02-24|url=https://covertactionmagazine.com/2021/02/24/how-did-a-fateful-cia-coup-executed-55-years-ago-this-february-24-doom-much-of-sub-saharan-africa/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220126041140/https://covertactionmagazine.com/2021/02/24/how-did-a-fateful-cia-coup-executed-55-years-ago-this-february-24-doom-much-of-sub-saharan-africa/|archive-date=2022-01-26|retrieved=2022-08-03}}</ref> | The [[CIA]] organized a coup against Nkrumah on 24 February 1966. At least 1,600 people died in the coup, which was also supported by [[Canada]] and the United Kingdom. The [[National Liberation Council]] (NLC) that took power after the coup [[Privatization|privatized]] state-owned businesses. The [[International Monetary Fund|IMF]] convinced the military junta to end Ghana’s industrialization program.<ref>{{Web citation|author=Charles Quist-Adade|newspaper=[[CovertAction Magazine]]|title=How Did a Fateful CIA Coup—Executed 55 Years Ago this February 24—Doom Much of Sub-Saharan Africa?|date=2021-02-24|url=https://covertactionmagazine.com/2021/02/24/how-did-a-fateful-cia-coup-executed-55-years-ago-this-february-24-doom-much-of-sub-saharan-africa/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220126041140/https://covertactionmagazine.com/2021/02/24/how-did-a-fateful-cia-coup-executed-55-years-ago-this-february-24-doom-much-of-sub-saharan-africa/|archive-date=2022-01-26|retrieved=2022-08-03}}</ref> | ||

In ''Challenge of the Congo'', Nkrumah summarized his view of the reason for the coup: "Ghana, in the forefront of the struggle for a free and united Africa and on the brink of a great industrial breakthrough which would have given true economic independence, had become too dangerous an example to the rest of Africa to be allowed to continue under a socialist-directed government."<ref>Nkrumah, Kwame. ''Challenge of the Congo''. 1967.</ref> | In ''[[Library:Challenge of the Congo|Challenge of the Congo]]'', Nkrumah summarized his view of the reason for the coup: "Ghana, in the forefront of the struggle for a free and united Africa and on the brink of a great industrial breakthrough which would have given true economic independence, had become too dangerous an example to the rest of Africa to be allowed to continue under a socialist-directed government."<ref>Nkrumah, Kwame. ''Challenge of the Congo''. 1967.</ref> | ||

In his 1978 book ''[[In Search of Enemies]]'', former CIA case officer [[John Stockwell]] wrote that the CIA, through omissions in their | In his 1978 book ''[[Library:In Search of Enemies|In Search of Enemies]]'', former CIA case officer [[John Stockwell]] wrote that the CIA, through omissions in their record keeping and distancing themselves from actions while setting the stage for them to occur, were able to maintain plausible deniability in many covert actions. He writes that this is how the coup in Ghana was handled, writing that the CIA station in Ghana played a "major role" in the overthrow of Nkrumah's government in 1966, writing:<blockquote>The Accra station was nevertheless encouraged by headquarters to maintain contact with dissidents of the Ghanian army for the purpose of gathering intelligence on their activities. It was given a generous budget, and maintained intimate contact with the plotters as a coup was hatched. So close was the station's involvement that it was able to coordinate the recovery of some classified Soviet military equipment by the United States as the coup took place. The station even proposed to headquarters through back channels that a squad be on hand at the moment of the coup to storm the Chinese embassy, kill everyone inside, steal their secret records, and blow up the building to cover the fact. This proposal was quashed, but inside CIA headquarters the Accra station was given full, if unofficial credit for the eventual coup, in which eight Soviet advisors were killed. None of this was adequately reflected in the agency's written records.<ref>Stockwell, John. ''In Search of Enemies: A CIA Story.'' 1978.</ref></blockquote>1965 U.S. security council memorandums from several months before the coup, not released until years later, show U.S officials discussing among themselves that pro-Western coup plotters in Ghana were keeping U.S. officials "briefed", and a U.S. security council staffer states that "we and other Western countries (including France) have been helping to set up the situation by ignoring Nkrumah's pleas for economic aid" hoping that this would "spark" the coup.<ref>Komer, Robert W. [https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v24/d253 "Memorandum From Robert W. Komer of the National Security Council Staff to the President’s Special Assistant for National Security Affairs (Bundy)."] Washington, May 27, 1965. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964-1968. Volume XXIV, Africa. Document 253. Office of the Historian, United States Department of State. [https://web.archive.org/web/20230311105443/https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v24/d253 Archived] 2023-03-11.</ref> Weeks after the coup, March 12 1966 U.S. internal documents discuss that the new, "almost pathetically pro-Western" regime should be given gifts of surplus grain to "whet their appetite" for further U.S. support.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

Nkrumah, who was living in exile in | Nkrumah, who was living in exile in Guinea after the coup, described the economic aftermath of the coup in Chapters 5 and 6 of ''Dark Days in Ghana'', where state-run enterprises and other resources were rapidly sold off:<blockquote>The only Ghanaians to benefit from such a sell-out were the African middle-class hangers-on to neo-colonialist privilege and the neo-colonialist trading firms. For the mass of [[Proletariat|workers]], [[Peasantry|peasants]] and farmers, the victims of the capitalist free-for-all, it meant a return to the position of "drawers of water and hewers of wood" to [[Imperial core|Western]] capitalism. [...] Businessmen from the U.S.A., from Britain, [[Federal Republic of Germany|West Germany]], [[State of Israel|Israel]] and elsewhere, flew into Ghana like vultures to grab the richest pickings. Virtually all the state-owned industries developed by my government were allowed to pass into private ownership. These included such enterprises as The [[Timber Products Corporation]], The [[Cocoa Products Corporation]], the [[Diamond Mining Corporation]], the [[National Steel Works]], the [[Black Star Shipping Line]], [[Ghana Airways]], and all the state-owned hotels.<ref>Nkrumah, Kwame. ''Dark Days in Ghana.'' 1968. Lawrence & Wishart, London.</ref></blockquote> | ||

===Post-coup=== | ===Post-coup=== | ||

| Line 53: | Line 50: | ||

===2010s-present=== | ===2010s-present=== | ||

Following an agreement signed on May 8, 2018 between Ghana's defense minister and the U.S. Ambassador to Ghana, the United States established the [[West Africa Logistics Network]] (WALN) at Ghana's largest airport, [[Kotoka International Airport]] in Accra, which hosts some of the U.S. armed forces and contractors. The agreement gives the U.S. soldiers the right to carry arms on duty, allows U.S. army and civilians to enter Ghana without passport nor visa but just identification cards, allows the U.S. army to not take responsibility for the death of any other person aside from U.S. military personnel, and third party issues involving U.S. military personnel will only be resolved according to the laws of the United States, among other preferential treatments.<ref>Maxwell Boamah Amofa. [https://www.modernghana.com/news/1217749/the-sandhurst-colonial-mentality-and-the-rule-of.html “The Sandhurst Colonial Mentality and the Rule of Law.”] Modern Ghana. March 13, 2023. [https://web.archive.org/web/20230314222209/https://www.modernghana.com/news/1217749/the-sandhurst-colonial-mentality-and-the-rule-of.html Archived] 2023-02-14.</ref> | Following an agreement signed on May 8, 2018 between Ghana's defense minister and the U.S. Ambassador to Ghana, the United States established the [[West Africa Logistics Network]] (WALN) at Ghana's largest airport, [[Kotoka International Airport]] in Accra, which hosts some of the [[United States Armed Forces|U.S. armed forces]] and contractors. The agreement gives the U.S. soldiers the right to carry arms on duty, allows U.S. army and civilians to enter Ghana without passport nor visa but just identification cards, allows the U.S. army to not take responsibility for the death of any other person aside from U.S. military personnel, and third party issues involving U.S. military personnel will only be resolved according to the laws of the United States, among other preferential treatments.<ref>Maxwell Boamah Amofa. [https://www.modernghana.com/news/1217749/the-sandhurst-colonial-mentality-and-the-rule-of.html “The Sandhurst Colonial Mentality and the Rule of Law.”] Modern Ghana. March 13, 2023. [https://web.archive.org/web/20230314222209/https://www.modernghana.com/news/1217749/the-sandhurst-colonial-mentality-and-the-rule-of.html Archived] 2023-02-14.</ref> | ||

In a 2022 interview published by [[Peoples Dispatch]], Ghanaian journalist [[Kwesi Pratt Jr.]] attested that the WALN had by then taken over one of the three terminals at the airport in Accra, and at this terminal, "hundreds of US soldiers have been seen arriving and leaving. It is suspected that they may be involved in some operational activities in other West African countries and generally across the [[Sahel]]."<ref name=":3">[[Vijay Prashad|Prashad, Vijay]]. [https://peoplesdispatch.org/2022/06/15/why-does-the-united-states-have-a-military-base-in-ghana/ “Why Does the United States Have a Military Base in Ghana?”] [[Peoples Dispatch]]. June 15, 2022. [https://web.archive.org/web/20230317061849/https://peoplesdispatch.org/2022/06/15/why-does-the-united-states-have-a-military-base-in-ghana/ Archived] 2023-03-17.</ref> | In a 2022 interview published by [[Peoples Dispatch]], Ghanaian journalist [[Kwesi Pratt Jr.]] attested that the WALN had by then taken over one of the three terminals at the airport in Accra, and at this terminal, "hundreds of US soldiers have been seen arriving and leaving. It is suspected that they may be involved in some operational activities in other West African countries and generally across the [[Sahel]]."<ref name=":3">[[Vijay Prashad|Prashad, Vijay]]. [https://peoplesdispatch.org/2022/06/15/why-does-the-united-states-have-a-military-base-in-ghana/ “Why Does the United States Have a Military Base in Ghana?”] [[Peoples Dispatch]]. June 15, 2022. [https://web.archive.org/web/20230317061849/https://peoplesdispatch.org/2022/06/15/why-does-the-united-states-have-a-military-base-in-ghana/ Archived] 2023-03-17.</ref> | ||

An analysis of the U.S. strategic interest in Ghana is discussed in the Peoples Dispatch article, stating that in 2001, a U.S. group associated with then-Vice President [[Dick Cheney]] published a National Energy Policy, in which was discussed the issue that the U.S. could no longer rely on the Middle East for its energy supplies, and that a shift to West Africa would be needed. Apart from West Africa's energy resources, the article notes that Ghana has huge national resources, such as gold, cocoa, iron, diamond, manganese, bauxite, oil and gas, lithium, and abundant water resources, including the largest man-made lake in the world. Apart from these resources, Ghana's location on the equator makes it valuable for agricultural development, and Ghana also has many highly educated English-speaking professionals. Meanwhile, the United States claims that its military presence on the African continent has to do with its "counterterrorism" campaign, as well as its aims to prevent the entry of [[People's Republic of China|China]] into Africa.<ref name=":3" /> | An analysis of the U.S. strategic interest in Ghana is discussed in the Peoples Dispatch article, stating that in 2001, a U.S. group associated with then-Vice President [[Dick Cheney]] published a National Energy Policy, in which was discussed the issue that the U.S. could no longer rely on the Middle East for its energy supplies, and that a shift to West Africa would be needed. Apart from West Africa's energy resources, the article notes that Ghana has huge national resources, such as gold, cocoa, iron, diamond, manganese, bauxite, [[Petroleum politics|oil]] and gas, lithium, and abundant water resources, including the largest man-made lake in the world. Apart from these resources, Ghana's location on the equator makes it valuable for [[Agriculture|agricultural]] development, and Ghana also has many highly educated English-speaking professionals. Meanwhile, the United States claims that its military presence on the African continent has to do with its "counterterrorism" campaign, as well as its aims to prevent the entry of [[People's Republic of China|China]] into Africa.<ref name=":3" /> | ||

The First National Congress of the [[Socialist Movement of Ghana]] (SMG), previously the Socialist Forum of Ghana (SFG), was held in 2021 in [[Winneba]].<ref name=":6" /><ref>Phillyp Mikell. [https://mronline.org/2021/10/05/ghanas-socialist-movement-a-revolutionary-experiment-in-communication/ “Ghana’s Socialist Movement: A Revolutionary Experiment in Communication.”] MR Online. October 6, 2021. [https://web.archive.org/web/20230320084904/https://mronline.org/2021/10/05/ghanas-socialist-movement-a-revolutionary-experiment-in-communication/ Archived] 2023-03-20.</ref> | The First National Congress of the [[Socialist Movement of Ghana]] (SMG), previously the Socialist Forum of Ghana (SFG), was held in 2021 in [[Winneba]].<ref name=":6" /><ref>Phillyp Mikell. [https://mronline.org/2021/10/05/ghanas-socialist-movement-a-revolutionary-experiment-in-communication/ “Ghana’s Socialist Movement: A Revolutionary Experiment in Communication.”] MR Online. October 6, 2021. [https://web.archive.org/web/20230320084904/https://mronline.org/2021/10/05/ghanas-socialist-movement-a-revolutionary-experiment-in-communication/ Archived] 2023-03-20.</ref> | ||

== Administrative divisions == | |||

Ghana is divided into 16 regions that are further subdivided into 212 districts and then into councils and unit committees. The 16 regions of Ghana are [[Ahafo]], [[Ashanti]], [[Bono]], [[Bono East]], [[Central (Ghana)|Central]], [[Eastern (Ghana)|Eastern]], [[Greater Accra]], [[North East (Ghana)|North East]], [[Northern (Ghana)|Northern]], [[Oti]], [[Savannah (Ghana)|Savannah]], [[Upper East (Ghana)|Upper East]], [[Upper West (Ghana)|Upper West]], [[Volta (Ghana)|Volta]], [[Western (Ghana)|Western]], and [[Western North (Ghana)|Western North]]. The national capital of Accra is located in the Greater Accra Region.<ref name=":2">[https://www.worldatlas.com/maps/ghana “Ghana Maps & Facts.]” WorldAtlas. February 24, 2021. [https://web.archive.org/web/20230316034205/https://www.worldatlas.com/maps/ghana Archived] 2023-03-16.</ref> | |||

==Economy== | ==Economy== | ||

Due to IMF neocolonialism, the Ghanaian cedi has an inflation rate of over 40%.<ref>{{Web citation|author=Nino Brown|newspaper=[[Liberation News]]|title=Interview with the Socialist Movement of Ghana: The IMF and the class struggle|date=2022-12-01|url=https://www.liberationnews.org/interview-with-the-socialist-movement-of-ghana-the-imf-and-the-class-struggle/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221201205220/https://www.liberationnews.org/interview-with-the-socialist-movement-of-ghana-the-imf-and-the-class-struggle/|archive-date=2022-12-01|retrieved=2022-12-02}}</ref> | Due to IMF neocolonialism, the Ghanaian [[cedi]] has an [[inflation]] rate of over 40%.<ref>{{Web citation|author=Nino Brown|newspaper=[[Liberation News]]|title=Interview with the Socialist Movement of Ghana: The IMF and the class struggle|date=2022-12-01|url=https://www.liberationnews.org/interview-with-the-socialist-movement-of-ghana-the-imf-and-the-class-struggle/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221201205220/https://www.liberationnews.org/interview-with-the-socialist-movement-of-ghana-the-imf-and-the-class-struggle/|archive-date=2022-12-01|retrieved=2022-12-02}}</ref> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Latest revision as of 17:33, 3 February 2024

| Republic of Ghana Gaana Adehyeman | |

|---|---|

[[Flag of Ghana|Flag]]

| |

Motto: "Freedom and Justice" | |

Anthem: "God Bless Our Homeland Ghana" | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Accra |

| Official languages | English |

| Area | |

• Total | 238,535 km² |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 32,103,042 |

| ISO 3166 code | [[ISO 3166-2:Template:ISO 3166 code|Template:ISO 3166 code]] |

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a capitalist state in West Africa which borders Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, and Togo. It was established in 1960, following the dissolution of the Dominion of Ghana by Kwame Nkrumah. Following the US backed overthrow of Kwame Nkrumah's government in '66, the country was plagued by a series of military regimes and neocolonialism. Liberal democracy would eventually be established in 1993 by former dictator Jerry Rawlings. Ghana currently stands as a two-party state in which political power is monopolized by the New Patriotic Party liberals and the National Democratic Congress social democrats.

History[edit | edit source]

Early history[edit | edit source]

Archaeological evidence indicates that present-day Ghana has been inhabited for many thousand years. The early Kingdom of Ghana (sometimes known as "Ghanata" or "Wagadugu") was one of the most powerful African empires for several hundred years.[1]

European arrivals[edit | edit source]

In 1471, the Portuguese arrived on the coast of Guinea. Over time, more Europeans arrived in Ghana, attracted by gold, ivory and timber. Eventually, enslaved Africans for plantations in the Americas became the focus of trade, and European powers such as England, the Netherlands, Portugal, Germany, France, Sweden and Denmark all competed in the slave trade for over 300 years. The Europeans traded weapons and manufactured goods for enslaved Africans, who were transported for across the Atlantic Ocean to work on plantations, in a system commonly referred to as the Atlantic slave trade.[1]

British colony[edit | edit source]

From 1821 until its independence in 1957, Ghana fell under British rule and was known as the Gold Coast. The Gold Coast was officially proclaimed a British crown colony in 1874. By this time, slavery had become illegal under British law, and so business in colonial Ghana focused more on exploiting cocoa, gold, timber and palm oil.

In 1947, J.B. Danquah, the president of the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), the Gold Coast's first opposition political party, invited Kwame Nkrumah to become the party's Secretary General.[2] Nkrumah was a proponent of socialist, anti-imperialist and Pan-Africanist ideas and had been abroad studying economics, sociology, theology, education and philosophy, in addition to organizing abroad for several years such as having a role in convening the Fifth Pan-African Congress in 1945.[3]

In February 1948, a group of unarmed ex-servicemen who had fought with the Gold Coast Regiment of the Royal West African Frontier Force in the Second World War set out on a march from Accra to the suburban residence of the British governor to present him with a petition of grievances. When they were ordered to stop, they refused, and the colonial police opened fire, killing three of the ex-servicemen. Angered by this unwarranted violence and the continued injustices suffered by the population in general, people in Accra took to the streets, and rioting spread throughout other towns and cities. This eventually resulted in 29 deaths and hundreds of other casualties after five days of rioting. On 12th March the governor ordered the arrest of "The Big Six," leading members of the UGCC, which included Kwame Nkrumah. The governor believed they were responsible for orchestrating the disturbances. They were detained but released a month later.[4]

During this time, Nkrumah was among those advocating for immediate political independence for the Gold Coast, while others of the UGCC were advocating for a more gradual approach to independence.[2][3]

Eventually, Nkrumah formed the Convention People's Party (CPP), advocating for "self-government now", which achieved rapid success and quickly became a major player on the nationalist political scene.

As the British colonial government continued to refuse to accept the popular demands of the people for self-government, Nkrumah called for a Positive Action campaign in 1950, a series of protests and strikes and a boycott of European goods, intended to fight colonialism through nonviolence and education.[5] In response to this, Nkrumah and other leaders were arrested and imprisoned. However, Nkrumah was released from jail after the CPP won the first election for the Legislative Assembly.

Nkrumah became Prime Minister in 1952, was re-elected in 1954 and 1956, and retained the position when Ghana declared independence from Britain in 1957.[1]

Independence[edit | edit source]

Ghana became independent from the United Kingdom in 1957, under Kwame Nkrumah's administration. Nkrumah's administration was socialist and Pan-Africanist in its leanings. A 1966 U.S. government internal memorandum describes Nkrumah as "strongly pro-Communist" and says that "Nkrumah was doing more to undermine our interests than any other black African."[6]

Nkrumah provided funding and training to members of the African National Congress in South Africa who wanted to overthrow apartheid.

Economically, independent Ghana was developed through Five Year Plans, including the First and Second Five Year Development Plans (1951-1956 and 1959-1964), as well as an uncompleted Seven Year Development Plan beginning in 1964, which was halted after an imperialist-backed reactionary coup regime took power in 1966. The Seven Year Development plan as well as the coup are described in detail in Nkrumah's 1968 book, Dark Days in Ghana.

1966 coup d'état[edit | edit source]

The CIA organized a coup against Nkrumah on 24 February 1966. At least 1,600 people died in the coup, which was also supported by Canada and the United Kingdom. The National Liberation Council (NLC) that took power after the coup privatized state-owned businesses. The IMF convinced the military junta to end Ghana’s industrialization program.[7]

In Challenge of the Congo, Nkrumah summarized his view of the reason for the coup: "Ghana, in the forefront of the struggle for a free and united Africa and on the brink of a great industrial breakthrough which would have given true economic independence, had become too dangerous an example to the rest of Africa to be allowed to continue under a socialist-directed government."[8]

In his 1978 book In Search of Enemies, former CIA case officer John Stockwell wrote that the CIA, through omissions in their record keeping and distancing themselves from actions while setting the stage for them to occur, were able to maintain plausible deniability in many covert actions. He writes that this is how the coup in Ghana was handled, writing that the CIA station in Ghana played a "major role" in the overthrow of Nkrumah's government in 1966, writing:

The Accra station was nevertheless encouraged by headquarters to maintain contact with dissidents of the Ghanian army for the purpose of gathering intelligence on their activities. It was given a generous budget, and maintained intimate contact with the plotters as a coup was hatched. So close was the station's involvement that it was able to coordinate the recovery of some classified Soviet military equipment by the United States as the coup took place. The station even proposed to headquarters through back channels that a squad be on hand at the moment of the coup to storm the Chinese embassy, kill everyone inside, steal their secret records, and blow up the building to cover the fact. This proposal was quashed, but inside CIA headquarters the Accra station was given full, if unofficial credit for the eventual coup, in which eight Soviet advisors were killed. None of this was adequately reflected in the agency's written records.[9]

1965 U.S. security council memorandums from several months before the coup, not released until years later, show U.S officials discussing among themselves that pro-Western coup plotters in Ghana were keeping U.S. officials "briefed", and a U.S. security council staffer states that "we and other Western countries (including France) have been helping to set up the situation by ignoring Nkrumah's pleas for economic aid" hoping that this would "spark" the coup.[10] Weeks after the coup, March 12 1966 U.S. internal documents discuss that the new, "almost pathetically pro-Western" regime should be given gifts of surplus grain to "whet their appetite" for further U.S. support.[6] Nkrumah, who was living in exile in Guinea after the coup, described the economic aftermath of the coup in Chapters 5 and 6 of Dark Days in Ghana, where state-run enterprises and other resources were rapidly sold off:

The only Ghanaians to benefit from such a sell-out were the African middle-class hangers-on to neo-colonialist privilege and the neo-colonialist trading firms. For the mass of workers, peasants and farmers, the victims of the capitalist free-for-all, it meant a return to the position of "drawers of water and hewers of wood" to Western capitalism. [...] Businessmen from the U.S.A., from Britain, West Germany, Israel and elsewhere, flew into Ghana like vultures to grab the richest pickings. Virtually all the state-owned industries developed by my government were allowed to pass into private ownership. These included such enterprises as The Timber Products Corporation, The Cocoa Products Corporation, the Diamond Mining Corporation, the National Steel Works, the Black Star Shipping Line, Ghana Airways, and all the state-owned hotels.[11]

Post-coup[edit | edit source]

1980s-1990s[edit | edit source]

1990s-2000s[edit | edit source]

The Socialist Forum of Ghana (SFG) was founded in 1993, with a mission to advance socialism and pan-Africanism in public discourse.[12]

2010s-present[edit | edit source]

Following an agreement signed on May 8, 2018 between Ghana's defense minister and the U.S. Ambassador to Ghana, the United States established the West Africa Logistics Network (WALN) at Ghana's largest airport, Kotoka International Airport in Accra, which hosts some of the U.S. armed forces and contractors. The agreement gives the U.S. soldiers the right to carry arms on duty, allows U.S. army and civilians to enter Ghana without passport nor visa but just identification cards, allows the U.S. army to not take responsibility for the death of any other person aside from U.S. military personnel, and third party issues involving U.S. military personnel will only be resolved according to the laws of the United States, among other preferential treatments.[13]

In a 2022 interview published by Peoples Dispatch, Ghanaian journalist Kwesi Pratt Jr. attested that the WALN had by then taken over one of the three terminals at the airport in Accra, and at this terminal, "hundreds of US soldiers have been seen arriving and leaving. It is suspected that they may be involved in some operational activities in other West African countries and generally across the Sahel."[14]

An analysis of the U.S. strategic interest in Ghana is discussed in the Peoples Dispatch article, stating that in 2001, a U.S. group associated with then-Vice President Dick Cheney published a National Energy Policy, in which was discussed the issue that the U.S. could no longer rely on the Middle East for its energy supplies, and that a shift to West Africa would be needed. Apart from West Africa's energy resources, the article notes that Ghana has huge national resources, such as gold, cocoa, iron, diamond, manganese, bauxite, oil and gas, lithium, and abundant water resources, including the largest man-made lake in the world. Apart from these resources, Ghana's location on the equator makes it valuable for agricultural development, and Ghana also has many highly educated English-speaking professionals. Meanwhile, the United States claims that its military presence on the African continent has to do with its "counterterrorism" campaign, as well as its aims to prevent the entry of China into Africa.[14]

The First National Congress of the Socialist Movement of Ghana (SMG), previously the Socialist Forum of Ghana (SFG), was held in 2021 in Winneba.[12][15]

Administrative divisions[edit | edit source]

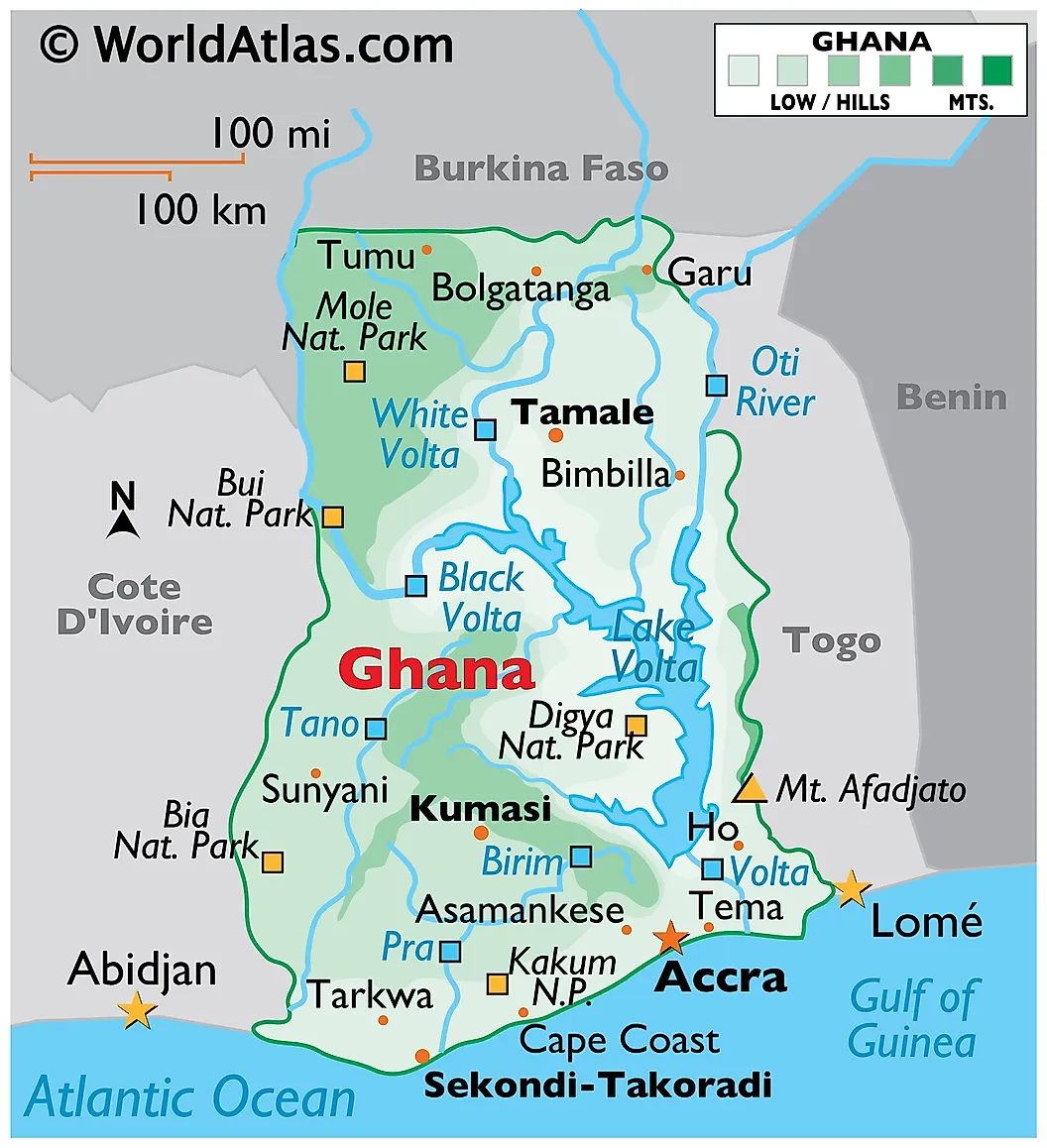

Ghana is divided into 16 regions that are further subdivided into 212 districts and then into councils and unit committees. The 16 regions of Ghana are Ahafo, Ashanti, Bono, Bono East, Central, Eastern, Greater Accra, North East, Northern, Oti, Savannah, Upper East, Upper West, Volta, Western, and Western North. The national capital of Accra is located in the Greater Accra Region.[16]

Economy[edit | edit source]

Due to IMF neocolonialism, the Ghanaian cedi has an inflation rate of over 40%.[17]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "History Timeline- Chronology of Important Events." West Africa, Early History. GhanaWeb. Archived 2023-03-13.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 “Ghanaians Campaign for Independence from British Rule, 1949-1951 | Global Nonviolent Action Database.” Swarthmore.edu. Archived 2023-03-19.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Abayomi Azikiwe. “Nkrumah and Ghana’s Independence Struggle.” Workers.org. Archived 2021-11-26.

- ↑ KESSE. “1948 Riots Which Triggered Ghana’s Independence.” Ghanaian Museum. February 28, 2022. Archived 2023-03-19.

- ↑ KESSE. “Positive Action Campaign Declared by Nkrumah.” Ghanaian Museum. January 8, 2022. Archived 2022-11-29.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Komer, Robert W. "Memorandum From the President’s Acting Special Assistant for National Security Affairs (Komer) to President Johnson." Johnson Library, National Security File, Memos to the President. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume XXIV, Africa. Document #260. Office of the Historian. United States Department of State. Archived 2022-05-18.

- ↑ Charles Quist-Adade (2021-02-24). "How Did a Fateful CIA Coup—Executed 55 Years Ago this February 24—Doom Much of Sub-Saharan Africa?" CovertAction Magazine. Archived from the original on 2022-01-26. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- ↑ Nkrumah, Kwame. Challenge of the Congo. 1967.

- ↑ Stockwell, John. In Search of Enemies: A CIA Story. 1978.

- ↑ Komer, Robert W. "Memorandum From Robert W. Komer of the National Security Council Staff to the President’s Special Assistant for National Security Affairs (Bundy)." Washington, May 27, 1965. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964-1968. Volume XXIV, Africa. Document 253. Office of the Historian, United States Department of State. Archived 2023-03-11.

- ↑ Nkrumah, Kwame. Dark Days in Ghana. 1968. Lawrence & Wishart, London.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Kulkarni, Pavan. “First National Congress of Socialist Movement of Ghana Charts a New Course for the Region.” Peoples Dispatch. August 3, 2021. Archived 2022-01-21.

- ↑ Maxwell Boamah Amofa. “The Sandhurst Colonial Mentality and the Rule of Law.” Modern Ghana. March 13, 2023. Archived 2023-02-14.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Prashad, Vijay. “Why Does the United States Have a Military Base in Ghana?” Peoples Dispatch. June 15, 2022. Archived 2023-03-17.

- ↑ Phillyp Mikell. “Ghana’s Socialist Movement: A Revolutionary Experiment in Communication.” MR Online. October 6, 2021. Archived 2023-03-20.

- ↑ “Ghana Maps & Facts.” WorldAtlas. February 24, 2021. Archived 2023-03-16.

- ↑ Nino Brown (2022-12-01). "Interview with the Socialist Movement of Ghana: The IMF and the class struggle" Liberation News. Archived from the original on 2022-12-01. Retrieved 2022-12-02.