More languages

More actions

| Burkina Faso 𞤄𞤵𞤪𞤳𞤭𞤲𞤢 𞤊𞤢𞤧𞤮 | |

|---|---|

Motto: La Patrie ou la Mort, Nous Vaincrons Homeland or Death, we will overcome | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Ouagadougou |

| Official languages | Bissa Dyula Fula Mooré |

| Membership | Confederation of Sahel States |

| Government | Military junta |

• President | Ibrahim Traoré |

• Prime Minister | Jean Emmanuel Ouédraogo |

| Area | |

• Total | 274,200 km² |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 22,489,126 |

| Currency | West African CFA franc (XOF) |

| Calling code | +226 |

| ISO 3166 code | BF |

| Internet TLD | .bf |

Burkina Faso is a landlocked country in West Africa. It borders Mali to the north, Niger to the east and Benin, Togo, Ghana and Ivory Coast to the south. It was formerly known as Upper Volta before being renamed by Thomas Sankara in 1984. Burkina Faso is often translated as "The Land of Upright People" and incorporates linguistic characteristics from two of the countries languages. The demonym "Burkinabé" incorporates another native language and translates to "Men of Integrity."[1]

History[edit | edit source]

Precolonization[edit | edit source]

Bura-Asinda Culture[edit | edit source]

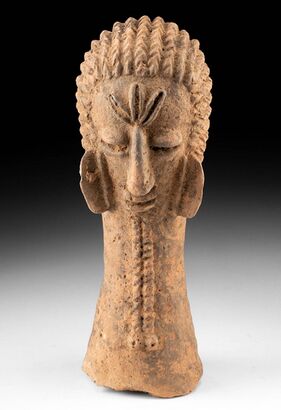

The Bura-Asinda Culture is an archaeological site located in the lower Niger River valley, spanning parts of southwest Niger and southeast Burkina Faso. This culture flourished from the 3rd century CE to the 13th century CE, though dates vary by site. Bura-Asinda is known primarily for its distinctive terracotta funerary art, ceramics, metallurgy, and burial practices, which were unknown to the outside world until the 1970s.[2]

It gets its name from the necropolis at the archaeological site called “Bura,” alongside the nearby settlement called “Asinda-Sikka.” It flourished during the West African Iron Age and was contemporaneous with the rise of the Ghana Empire and the earlier phases of the Mali Empire, though it had a completely distinct culture from them. It transitioned from village-level production to more complex social formations rooted in control of surplus, metallurgy, and long-distance trade.[3]

The site was discovered accidentally in 1975, though excavations did not begin until 1983, when they were conducted by the Institut de Recherches en Sciences Humaines. The Bura Necropolis is famous for its three-dimensional terracotta statues, phallic funerary urns, and stylized human head pottery. Unlike other cultures, the Bura people buried their dead in a standing, crouching position inside these large terracotta tubes; they were often buried so that only the head of the terracotta tube or statue was visible. Within the necropolis, differences in the amount of pottery, various metal goods, and human remains indicate social differentiation and stratification.[4]

Outside the Bura Necropolis, excavations show ironworking debris and furnaces at the sites. Iron production was the engine of agricultural intensification and forest clearing and also benefited the emerging elites by enabling them to defend their property and labor. These sites were located on elevated mounds near rivers, which was strategic for agriculture, grazing, and trade routes across the Sahel. The Bura people artistically created a unique artistic style that was looted and showcased in the imperial core. It was characterized by anthropomorphic figures typically riding horses; as many of the figures were depicted as riders on horses, due to cavalry being significant within their society.[4]

Mossi Kingdoms[edit | edit source]

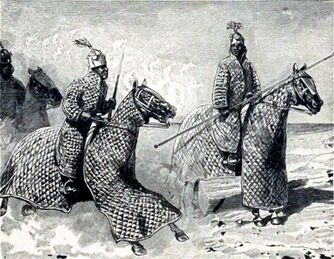

The Mossi Kingdoms were a network of connected kingdoms; the most important were Tenkodogo (the Mother Kingdom), Ouagadougou, Yatenga, and Boussouma. All of these kingdoms emerged in what is now Burkina Faso between the 11th and 15th centuries CE. The Mossi Kingdoms emerged from sedentary farming communities in the Sudanian–Sahelian transition zone. Iron adoption increased agricultural surpluses and allowed for expanded cultivation; these surpluses were appropriated by the emerging chiefs. Iron adoption also aided warrior lineages through the introduction of iron weaponry, which helped consolidate territory and extract tribute from the peasantry. These conditions combined to create an environment in which control of land, labor, and policing naturally formed the ruling class and the kingdom.[5]

In order to justify their rule, the ruling class had to manufacture a charter myth that justified their right to govern through lineage. It was called The Legend of Yennenga, and the story goes as follows:[5]

A warrior princess named Yennenga was a beautiful and skilled fighter. Her father, King Nedega of the Dagbon Kingdom, refused to let her marry, as her skills as a warrior were not worth losing. Yennenga, unhappy with her father’s decision, planted a field of wheat and let it rot to make a point about how she was withering without a family of her own. Her father did not listen and imprisoned her, but she later escaped by disguising herself as a man and, with the help of a loyal horseman, fled northwards on her stallion. After a long journey on horseback, her tired horse led her to a forest, where she met a man called Riale, a solitary elephant hunter. Riale soon discovered her identity, and they fell in love, eventually marrying and having a son they named Ouedraogo, meaning “stallion,” in honor of the horse that allowed her to flee her father. When Ouedraogo came of age, he decided to meet his grandfather, King Nedega, who was delighted to find his daughter alive and to meet his grandson. King Nedega gifted Ouedraogo cavalry and various goods, which he used to establish Tenkodogo, the mother kingdom of the Mossi Kingdoms.

These charter myths served to legitimize the authority of the warrior lineages that monopolized control over taxation, labor, and religious power, in order to justify their hierarchy of peasantry, religious priests, and the nobility of chieftains and the warrior caste. The Mossi Kingdoms, though they varied, were all monarchies in which the king ruled through a hierarchy of village chiefs, and all political authority was concentrated within the king and the noble circle, which fused military command, control of land, and spiritual rituals that bound peasants into these obligations. Land was owned by the ruling class, but the peasantry existed in usufruct and clientelist arrangements, meaning they used the land while the fruits of their labor were controlled by the nobility, typically the village chiefs of each village within the Mossi Kingdoms.[5]

The most notable historical feature of the Mossi Kingdoms is their resistance to the influence of neighboring empires such as the Ghana Empire, the Mali Empire, and the Songhai Empire, though they did trade with these states, which intensified the extraction of surplus and provided the rulers with luxury goods that reinforced social hierarchies. The Mossi Kingdoms maintained a notable amount of cavalry and infantry due to local recruitment through debt incurred from land use; these policies enabled them to remain separate from neighboring states. This separation was not merely cultural but was the result of Mossi control over the peasantry through agricultural and military surplus.[3]

Kong Empire[edit | edit source]

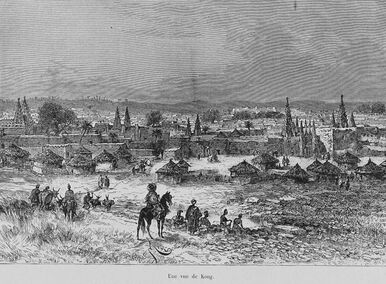

The Kong Empire, also known as the Watarra Empire, emerged from the city of Kong in present-day Ivory Coast, though it later expanded into Burkina Faso. It arose as a result of extensive long-distance Sahel–forest trade with Muslim merchant networks known as the Dyula, who acted as a commercial diaspora linking gold, ivory, kola nuts, and slaves from the rainforests to the trans-Saharan markets. This commercial system, combined with the agricultural surplus produced by the local peasantry, created the material conditions for an urban commercial capital, with authority concentrated in the hands of Muslim merchants who controlled trade routes, taxation, and tribute.[3]

The state is therefore by no means a power imposed on society from without; just as little is it “the reality of the moral idea,” “the image and the reality of reason,” as Hegel maintains. Rather, it is a product of society at a particular stage of development; it is the admission that this society has involved itself in insoluble self-contradiction and is cleft into irreconcilable antagonisms which it is powerless to exorcise. But in order that these antagonisms, classes with conflicting economic interests, shall not consume themselves and society in fruitless struggle, a power, apparently standing above society, has become necessary to moderate the conflict and keep it within the bounds of “order”; and this power, arisen out of society, but placing itself above it and increasingly alienating itself from it, is the state.

— Frederick Engels, Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State, IX. Barbarism and Civilization

Political authority in Kong fused merchant capital, military force, and religious legitimacy to regulate trade, resolve legal disputes, and extract revenue from peasants and caravans. Kong was essentially a commercial empire, protected by a decentralized military that safeguarded merchants’ property and kept trade routes open. Ivory, gold, kola nuts, and slaves were commodities moving through the capital’s markets and caravan corridors, supplied in part by the peasantry through their agricultural surplus and labor. Artisans, especially ironworkers and leatherworkers, served both local needs and the commercial economy. In essence, a merchant oligarchy, typically Muslim and fluent in Arabic, dominated long-distance trade and formed a bourgeoisie within Kong.[6]

These merchants used military force to enforce their commercial privileges and protect their property. As wealth concentrated in the hands of merchant families, social stratification followed. Religious elites, such as Islamic qadis, played both religious and administrative roles, facilitating credit, literacy, and record-keeping, all essential to capital accumulation. The peasantry formed a mass of producers whose labor was foundational to the urban economy. Authority rested on those who policed the trade routes and ensured safe passage, which was fundamental to commerce. Because of this, the military was crucial, and the merchants maintained a notable military force, which they used to incorporate surrounding villages into the empire and to demand corvée and tribute.[6]

The Kong Empire interacted with larger Sahelian states, such as the successors of the Mali Empire, the Lobi and Gur peoples, and the Wassoulou Empire in the late 19th century. However, everything changed when the Kong Empire was drawn into the global circuit of accumulation with the colonial invasion of the region, as the imperial core completely undermined the older commercial–agrarian structures. The late 19th century brought catastrophe to Kong: the Wassoulou Empire attacked and sacked the city, and shortly thereafter, the French began to forcibly impose new boundaries and administrative structures. The French colonial administration annexed the region, incorporating the former Gwiriko lands into the colony of Upper Senegal and Niger, and eventually into Upper Volta.[7]

Neocolonization[edit | edit source]

The Upper Volta was colonized by the French and became independent in 1960. After independence, it became the neocolonial Republic of Upper Volta, which was one of the poorest and least literate countries in the world. Before the Sankara-led Burkinabé Revolution in 1983, the life expectancy was only 40 years and only 2% of the population could read.[8]

The first president after independence was Maurice Yaméogo from 1960 to 1966. On January 3, 1966 he was forced to resign following an uprising led by the labor movement. Following this, Aboubacar Sangoulé Lamizana became head of state from January 3, 1966 until November 25, 1980.[9][10][11]

On November 25, 1980, General Aboubacar Sangoulé Lamizana was overthrown by a military coup led by Colonel Saye Zerbo.[11] On November 7, 1982, Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo along with a group of officers overthrew Saye Zerbo and established the Provisional Committee for the Salvation of the People, later called the Committee for the Salvation of the People. Ouédraogo became head of state and appointed Captain Thomas Sankara as Prime Minister.[12]

Revolution[edit | edit source]

See main article: Burkinabé Revolution

4 August uprising[edit | edit source]

In 1983, Prime Minister and former Secretary of State Thomas Sankara invited Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi to Upper Volta without permission from President Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo. Protests began in May after Ouédraogo arrested Sankara. Blaise Compaoré led a military coup that appointed Sankara president on 4 August 1983.

Revolutionary government[edit | edit source]

Within weeks, Sankara's government vaccinated 2.5 million children and began a literacy campaign. By 1987, the literacy rate had increased to 73%. Burkina Faso planted ten million trees to prevent desertification and built roads and railroads. Sankara redistributed land from feudal lords to the peasants, and wheat production per hectare more than doubled.[8]

Sankara attempted to create a currency union with Ghana and avoid trading with the franc. He allied with other revolutionary states such as Cuba. In order to sabotage Burkina Faso, France cut off financial aid. The Liberian warlord Charles Taylor asked Sankara for assistance in overthrowing Samuel Doe, but Sankara rejected.[13]

Restored neocolonial rule[edit | edit source]

Sankara's deputy, Blaise Compaoré, met with Charles Taylor, Chadian president Idriss Déby, and a French official in Mauritania while plotting a counterrevolution.[13]

On 15 October 1987, Blaise Compaoré murdered Sankara and took power of the country. He privatized natural resources and joined the IMF.[8] Reagan funded Compaoré's military after the coup. The Obama regime gave $35 million to Compaoré's military.[13]

Compaoré was overthrown in a popular uprising in 2014 and fled to the Ivory Coast, but Burkina Faso remained under a neocolonial government. Trump gave another $100 million to the Burkinabé military.[13]

Burkina Faso issued an arrest warrant for Compaoré in 2016, though the Ivory Coast did not approve extradition. Compaoré was convicted of Sankara's assassination on 6 April 2022.[14]

2022 coups[edit | edit source]

In January 2022, a group of nationalist military officers overthrew President Roch Kaboré, a wealthy comprador and established the Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration (PMSR). Paul-Henri Damiba took power and was initially popular. He expelled hundreds of French troops but failed to defeat Salafi jihadists.[15]

In September 2022, Ibrahim Traoré led an anti-imperialist, Pan-Africanist coup, taking leadership of the PMSR. In February 2023, he met with the governments of Guinea and Mali and proposed creating a federation. He criticized the African Union for siding with the West.[16] Traoré appointed Apollinaire Tambèla, a Sankara loyalist, as prime minister to help with the "refoundation of the nation."[15]

The Traoré government moved to secure sovereignty over the country. The military successfully won the trust of the people by leading a largely successful campaign against the militias. In November 2023, the Traoré government approved plans for the country's first gold refinery in an effort to move up the international division of labor.[17] In June, private land developers were barred from participating in urban planning projects, and limited to five hectares of land.[18]

On 16 September 2023, in response to threats from the French-backed Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali formed a collective defense pact called the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), in which an attack on one of the countries is regarded as an attack on the other members.[19][20]

Membership in the AES[edit | edit source]

On 28 January 2024 the leaders of the three countries declared intent to withdraw from ECOWAS. The withdraw was completed 29 January 2025. On the same date, the AES common passport became active.[21]

On 6 July 2024 the confederation treaty was signed, aimed at strengthening the previous AES defense pact, with the long-term goal of creating a single sovereign Sahel state with common citizenship, economy, and government.[22]

The Traoré government nationalized two gold mines on 27 August 2024 after UK-based Endeavor Mining overvalued the mines in a sale to Lilium Mining. The government stepped in to solve the ensuing legal dispute between the companies by purchasing the mines at a fraction of the 300 million USD faulty valuation.[17] The two mines, along with three others, were completely nationalized in June 2025.[23]

In December 2024, Traoré inaugurated an 8.9 million USD tomato processing plant. Alongside other new tomato processing facilities, Traoré sought to reduce the country's dependence on processed tomato imports. Burkina Faso produced the fourth largest amount of tomatoes in the region during 2022, yet the same year tomato puree imports totaled 8 million USD.[24]

On 5 February 2025, the Minister of the Economy and Finances announced a complete land nationalization and banned foreigners from holding rural land titles.[18]

The Confederation launched the Alliance of Agricultural Seed Producers of the Sahel (APSA-Sahel) on 7 April 2025 to develop, distribute and market specialized seeds for the harsh climate. Without the partnership of large agribusinesses which consider their modified seeds as intellectual property, the APSA will facilitate free movement of seeds between people and across confederation state borders.[25]

Traoré attended the 2025 Moscow Victory Day Parade in May 2025 where he deepened and defined Burkina's relationship with the Russian Federation. Traoré asserted that the Salafi jihadists active in the Sahel, themselves resultant from the 2011 NATO war on Libya, functionally serve imperialist interests by destabilizing the states of the region. In regards to food sovereignty and aid, he stated: “We made a promise to President Putin that we no longer wish to be supplied with wheat because we are going to produce the wheat. And I’ll keep this promise because we have started to produce the wheat in [sufficient] quantities to satisfy the local demand.” Traoré also declared his intention for Burkinabés to be educated in the sciences with Russian support “so that we can develop our own production, industry, and engineering.”[26]

On 21 June 2025 Burkina Faso celebrated National Tree Day and set the goal of planting 5 million trees in a single hour, and 20 million trees before the end of the year, in the fight against desertification. It is desired for each province to keep a publicly owned medicinal plant nursery to further healthcare access.[27]

On January 6, 2026, Minister of Security Mahamadou Sana reported in a RTB news broadcast that a destabilization plot targeted at state institutions had been foiled. He reported that the plan had been intended to play out on January 3 and would have included a series of assassination attempts against civilian and military authorities, including against President Traoré. The security minister attributed the plan primarily to Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba.[28]

Living standards[edit | edit source]

According to April 2022 data, 40% of the Burkinabé population lived in poverty. Only a third of adults were literate, and under 20% had electricity. The country ranked 144/157th in World Bank quality of living standards.[13]

LGBT rights[edit | edit source]

On September 1, 2025, the Transitional Legislative Assembly passed the Personal and Family Code, which criminalized homosexuality and similar practices with 2 to 5 years in prison and a fine as punishment. According to the Minister of Justice, Rodrigue Bayala, repeat offenders that are not of Burkinabe nationality will be deported.[29]

External links[edit | edit source]

- Government of Burkina Faso (French: Gouvernement du Burkina Faso)

- Presidency of Burkina Faso (French: Présidence du Faso)

- Government Information Service of Burkina Faso (French: Service d'Information du Gouvernement du Burkina Faso)

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Cooperation and Burkinabè Abroad (French: Ministère des Affaires Etrangères, de la Coopération et des Burkinabè de l’Extérieur)

- Burkina Faso Radio and Television Broadcasting (RTB) (French: Radiodiffusion Télévision du Burkina)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Dr. Y. (2013-09-12). "Why the name: Burkina Faso?" African Heritage. Archived from the original on 2025-05-10. Retrieved 2025-06-16.

- ↑ Michelle Gilbert (2020). Bura Funerary Urns: Niger Terracottas: An Interpretive Limbo?.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 McIntosh, Roderick J (1998). The Peoples of the Middle Niger: The Island of Gold.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 S. Terry Childs, David Killick. Indigenous African Metallurgy: Nature and Culture.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Skinner, Elliott P. (1964). The Mossi of the Upper Volta: the political development of a Sudanese people.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Timothy Insoll (2005). The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa.

- ↑ Richard L. Roberts (1987). Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Curry Malott (2020-12-21). "Thomas Sankara: Leadership and action that inspires 71 years later" Liberation School. Archived from the original on 2022-04-04. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ↑ "Maurice Yaméogo". Présidence du Faso. Retrieved 2026-01-10.

- ↑ David Zuber (2022-03-21). "Maurice Yaméogo (1921-1993)" BlackPast. Archived from the original on 2024-08-09.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Aboubacar Sangoulé Lamizana". Présidence du Faso. Retrieved 2026-01-10.

- ↑ "Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo". Présidence du Faso. Retrieved 2026-01-10.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Jeremy Kuzmarov (2022-04-29). "This Man Pulled the Trigger, But Did the CIA and DGSE Put the Idea in His Head and the Gun in His Hand?" CovertAction Magazine. Archived from the original on 2024-11-16.

- ↑ Tanupriya Singh (2022-04-08). "Blaise Compaoré convicted for the murder of revolutionary Burkinabé leader Thomas Sankara" Peoples Dispatch. Retrieved 2025-06-16.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ben Norton (2023-07-31). "Burkina Faso’s new president condemns imperialism, quotes Che Guevara, allies with Nicaragua, Venezuela, Cuba" Geopolitical Economy Report. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ↑ Vijay Prashad, Kambale Musavuli (2023-08-01). "Niger Is the Fourth Country in the Sahel to Experience an Anti-Western Coup" Independent Media Institute. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Steve Lalla (2024-09-10). "Burkina Faso Nationalizes UK Goldmines" Orinoco Tribune. Retrieved 2025-06-16.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Burkina Faso Nationalises All Land" (2025-02-17). Prensa Latina. Retrieved 2025-06-16.

- ↑ Alex Anfruns (2024-11-09). "The confederation of Sahel States and their struggle against neo-colonialism" Peoples Dispatch. Retrieved 2025-06-16.

- ↑ "Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso sign Sahel security pact" (2023-09-16). Reuters. Archived from the original on 2023-09-17. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ↑ Nicholas Mwangi (2025-01-29). "Sahel states exit ECOWAS, launch regional passport and joint military" Peoples Dispatch. Retrieved 2025-06-16.

- ↑ "Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso military leaders sign new pact, rebuff ECOWAS" (2024-07-06). Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2025-08-11.

- ↑ "Burkina Faso completes nationalisation of five gold mining assets" (2025-06-12). Reuters. Retrieved 2025-06-16.

- ↑ "President Ibrahim Traoré inaugurates new US$8.9M tomato processing plant in Burkina Faso" (2024-12-18). Food Business Middle East & Africa. Retrieved 2025-06-16.

- ↑ Oluwasegun Sanusi (2025-07-04). "Confederation of Sahel States Launches Alliance for Agricultural Seed Sovereignty" West Africa Weekly. Retrieved 2025-08-11.

- ↑ Pavan Kulkarni (2025-05-12). "“Terrorism we are witnessing today comes from imperialism”, Burkina Faso’s President Ibrahim Traoré tells Putin" Peoples Dispatch. Retrieved 2025-06-16.

- ↑ Pedro Stropasolas (2025-06-24). "In the fight against desertification, Burkina Faso mobilizes to plant 5 million trees in one hour" People's Dispatch. Retrieved 2025-08-11.

- ↑ Cédric KABORE (2026-01-07). "Burkina Faso: When the Minister of security comes out to set the record straight on the foiled destabilisation attempt" Sahel Liberty News.

- ↑ "Burkina : Les pratiques homosexuelles et assimilées désormais punies par la loi" (2025-09-01). L'Agence d'Information du Burkina. Archived from the original on 2025-09-04.