More languages

More actions

(quotes link) Tag: Visual edit |

(cats) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 135: | Line 135: | ||

[[Category:Former heads of state]] | [[Category:Former heads of state]] | ||

[[Category:Targets of bourgeois media]] | [[Category:Targets of bourgeois media]] | ||

[[Category:Russian Marxists]] | |||

[[Category:Communist leaders]] | [[Category:Communist leaders]] | ||

Revision as of 23:35, 27 August 2023

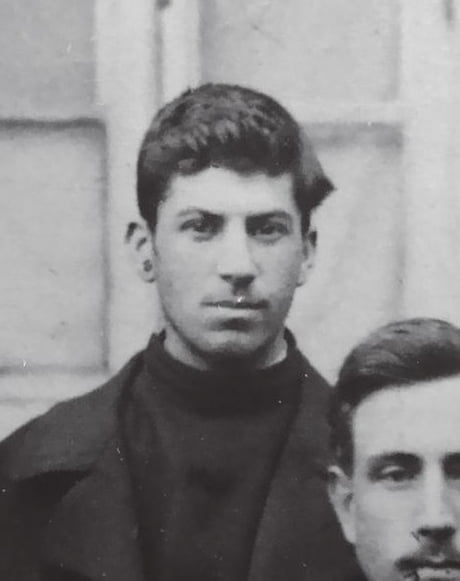

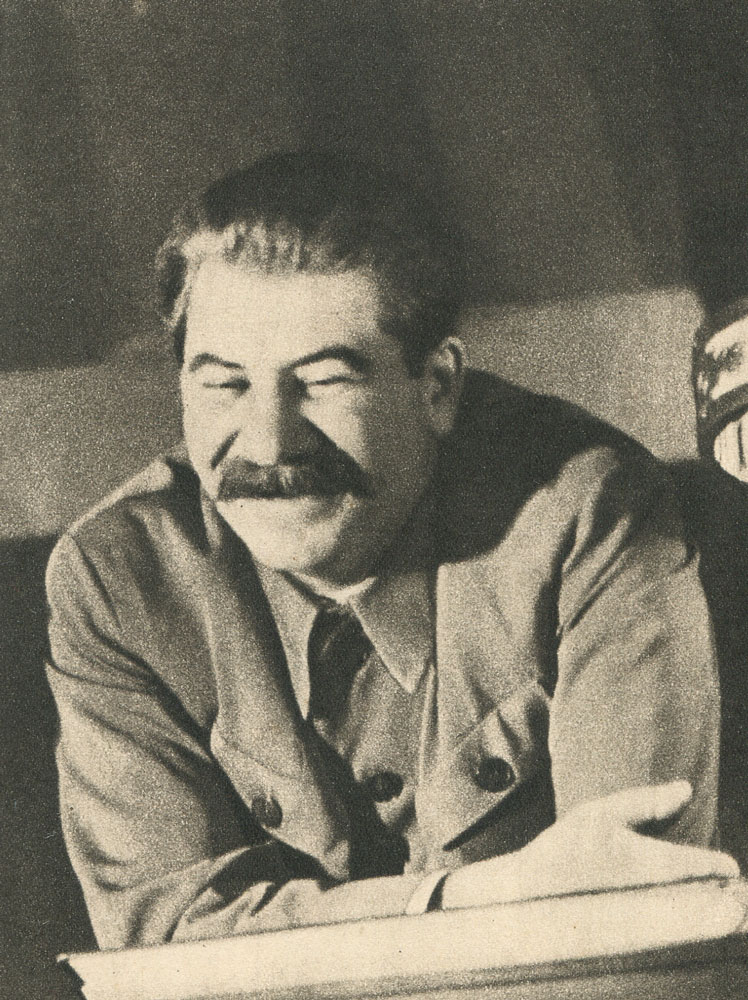

Josef Stalin Иосиф Сталин იოსებ სტალინი | |

|---|---|

Portrait of comrade Stalin | |

| Born | Ioseb Besarionis dze Jugashvili December 21, 1878 Gori, Tiflis Governorate, Russian Empire (present-day Georgia) |

| Died | March 5, 1953 (aged 74) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Cause of death | Cerebral hemorrhage |

| Nationality | Georgian |

| Political orientation | Marxism–Leninism |

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

Iósif Vissariónovich Dzhugashvili (21 December 1878 – 5 March 1953), better known as Joseph Stalin, was a Georgian Marxist–Leninist revolutionary, politician, and political theorist, as well as the democratically elected[1] leader of the Soviet Union, serving as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 3 April 1922 to 16 October 1952.

Stalin played a central role in the revolutionary activities of the Bolsheviks, a faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) led by Vladimir Lenin, before and during the October Revolution. After the Revolution, he was appointed General Secretary of the Communist Party by Lenin. Upon Lenin's death in 1924, Stalin assumed his role as the leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Stalin oversaw the great period of collectivisation and industrialisation which transformed the USSR from an illiterate peasant backwater to a great power by the late-1930s and '40s which, despite initial setbacks, played a principal role in the defeat of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan during World War II.

Stalin has a complicated history and equally complicated public image largely as a result of decades of anti-communist propaganda. In much of the Western world and in the former Soviet Union, he is commonly portrayed as a dictator, though even the CIA recognised internally in 1955 that there was collective leadership during his time in office.[2]

Life and work

Early life (1878–1899)

Iósif Vissariónovich Dzhugashvili was born on 21 December, 1878[a] in Gori,[b] a city of the Russian Empire, in the family of a craftsman, later a worker of a shoe factory. Like his parents, Stalin was an ethnic Georgian, and he grew up speaking the Georgian language. Both his father and his mother came from a family of serfs.[3]

Stalin's revolutionary activities can be traced to his time as a student after 1894, when he joined the Orthodox Theological Seminary in Tiflis.[4][5] In 1896 and 1897, Stalin was a part of Marxist study groups in the seminary, and in August 1898, he formally joined the Tiflis branch of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) and began to conduct propaganda work among the workers in the Tiflis railway workshops. An avid reader, he read Capital and the Manifesto of the communist party, written by Karl Marx, subsequently taking a profound interest in Marxism. At that time, he became acquainted with some of Lenin's articles criticizing the Narodniks and the "Legal Marxists".[6] In 1899, Stalin was expelled from the seminary for the propaganda of Marxism, and he went to an illegal position and became a professional revolutionary.

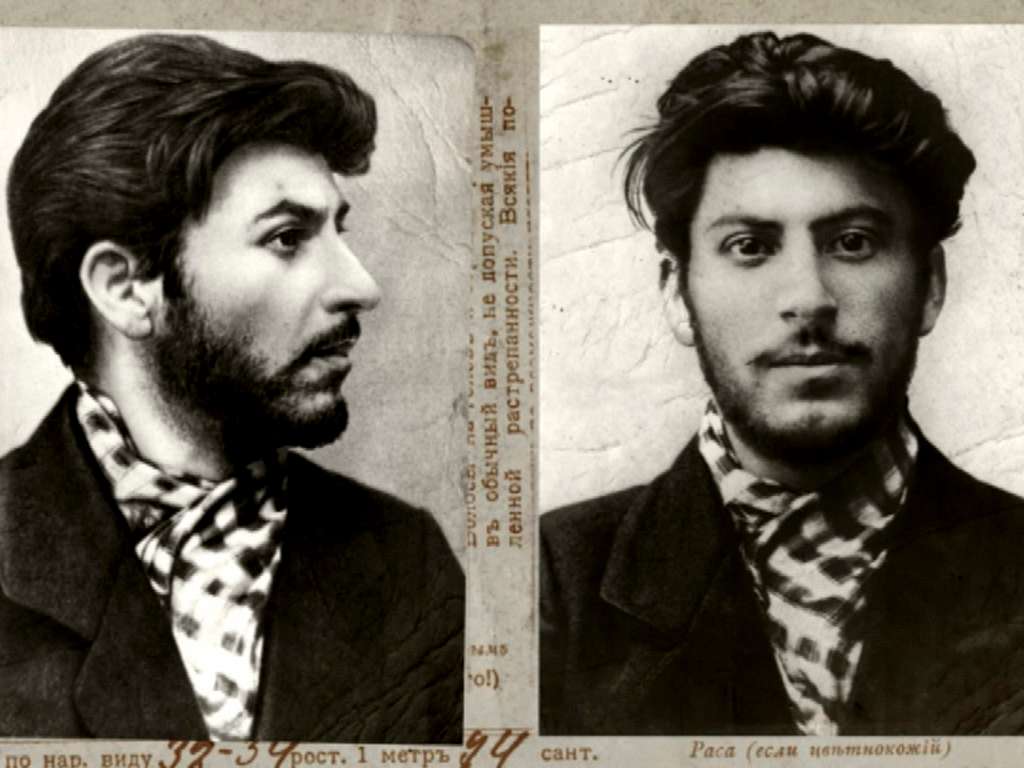

Beginning of revolutionary activities (1900–1917)

While organizing in the Caucasus, Stalin exposed the Mensheviks as liberal reformists. He met Lenin in person for the first time at a Bolshevik conference in Tampere, Finland in 1905.[7] In 1912, the party elected Stalin to the Central Committee even though he was in exile at the time.[8] In 1912, Stalin helped found the newspaper Pravda.[9]

After the February Revolution, Stalin returned from exile in Siberia. He called for an overthrow of the provisional government and opposed the imperialist First World War. At a party conference in April 1917, he argued with Bukharin and Pyatakov, who did not support the right of nations to self-determination. In September, Stalin opposed participating in the bourgeois Provisional Council and called for a revolution instead.

On 29 October 1917, the Central Committee elected Stalin as head of the Party Center to direct the October Revolution.[10]

Civil War (1918–1920)

In summer 1919, the Central Committee sent Stalin, Voroshilov, Orjonikidze, and Budyonny to the southern front, where he organized an attack against Anton Denikin from the Donbass. The Red Army defeated Denikin in October 1919 and liberated all of Ukraine by early 1920.[11]

Establishment of the U.S.S.R. (1921–1924)

After the defeat of the interventionists and the civil war, when in connection with the transition to a peaceful economic construction of the anti-party groups launched a struggle against the party line developed by Lenin, Stalin defended the Leninist line and fought against anti-party groups and factions (Trotskyists, "workers' opposition"). At the 10th Congress of the Party (1921) Stalin presented "The Report on the next tasks of the Party in the national question". After the 11th Party Congress (1922) the Plenum of the Party Central Committee elected Joseph Stalin as the Secretary General of the Central Committee.

Under the leadership of V. I. Lenin, the Party during this period carried out extensive work on the creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Lenin believed that the USSR should be a voluntary union of equal and sovereign union republics. On this question, Stalin at first took the wrong stand, putting forward the project of so-called "autonomization", i.e., the entry into the RSFSR of other Soviet republics on the rights of autonomous units. V. I. Lenin strongly opposed this proposal, criticized Stalin's mistakes in conducting the national policy, his partiality to the manifestations of great-power chauvinism. The Leninist principles were accepted by the Central Committee and formed the basis of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. The report on the formation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (1922) was made at the 1st Congress of Soviets of the USSR by the order of the Central Committee of the RCP(b) by I.V. Stalin in view of Lenin's illness.

After Lenin's death, the Communist Party, under the leadership of the Central Committee, firmly and confidently led the Soviet people along the path of implementation of Lenin's precepts, on the path of building socialism. At this time, Stalin made a number of works that were of great importance in the protection and propaganda of Leninism and in the ideological defeat of the currents hostile to Leninism. In this respect, a great role was played by Stalin's work "On the Foundations of Leninism" (1924), which set forth the basic issues of Leninism and disclosed the new things that Lenin contributed to Marxism. The defense by I. V. Stalin, together with other leaders of the Party, of the Leninist theory of the possibility of the victory of socialism initially in one, separate country, and of the possibility of the victory of socialism in the USSR in the capitalist encirclement, was of particular importance in the struggle against the Trotskyists.[citation needed]

14th Party Congress (1925–1926)

Based on the instructions of V. Lenin, who developed a scientifically sound program for building socialism in the USSR, the party set a course for the socialist industrialization of the country. This line was set out in the political report of the Central Committee at the XIV Party Congress (1925), made by Stalin. The report emphasized that the essence of industrialization was the priority development of heavy industry, and first of all the mechanical engineering, the fundamental difference of socialist industrialization, which was inextricably linked with the improvement of the working people's material condition, from the capitalist one, which was held by means of colonial seizure, robbery and ruthless exploitation of the working people.

In early 1926 he published a book of Stalin "Toward Leninism", which was criticized opportunistic views of Zinovievites, who were descending to the ideological positions of Trotskyism and wanted wanted the Soviet Union to stay mostly agricultural and import its industry from capitalist countries.[12] At the 15th Party Conference (November 1926) Stalin made a report "On the Social Democratic bias in our party" and at the VII Extended Plenum of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (December 1926) with the report "About the Social Democratic bias in our party again". Both these reports played an important role in rallying the party ranks under the banner of Leninist ideas and in exposing the Trotskyites, their capitulation to capitalism and their disorganizing activities.

Collectivization campaign (1927–1934)

Based on the successes of socialist industrialization and guided by Lenin's cooperative plan, the 15th Congress of the CPSU (b) (1927) put forward collectivization of the agriculture as the most important task of the Party and Soviet people. These questions were covered in the political report of the Central Committee of the Party, made at the Congress by I. V. Stalin. During this period, an anti-party group of right-wing opportunists—Bukharin, Rykov, Tomsky and others—openly opposed the general line of the Party. In the reports of Stalin "On the industrialization of the country and the right deviation in the CPSU (b)" (1928), "On the right - the deviation in the CPSU (b)" (1929), etc. exposed the line of the right opportunists, which expressed the ideology of the kulak, rich peasant class.

In 1930, Stalin released the Pravda article "Dizzy with Success," criticizing people who were overenthusiastic about collectivization and forced peasants onto collective farms. This issue was most severe in Transcaucasia and Central Asia, where collectivization was not scheduled to finish until 1933.[13]

At the XVI Congress of the CPSU(b) (1930) and XVII Congress of the CPSU(b) (1934) Stalin made reports on the work of the Central Committee of the Party. During this period, the Communist Party and the Soviet state carried out an all-out offensive of socialism against the capitalist elements. Under the conditions of a tense international situation, the country overcame enormous difficulties in order to put an end to the technical and economic backwardness within the shortest historical period. In pursuing a course of priority and predominant development of heavy industry, the Party made decisive progress in the socialist industrialization of the country and the collectivization of agriculture.

1936 Constitution and later (1936–1939)

Stalin helped draft the 1936 Constitution of the Soviet Union, which the Eighth Congress of Soviets approved in November 1936.[14] This constitution remained in effect until 1977.

In 1938 Stalin wrote his work "On dialectical and historical materialism", which gives a brief coverage of the foundations of Marxist-Leninist philosophy and shows its importance for the practical work of the Party.

In March 1939 the 18th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks was held. In the report of the Central Committee at the Congress Stalin outlined the program developed by the Central Committee of the struggle of the party and the Soviet people for the completion of building a socialist society in the gradual transition from socialism to communism.[citation needed]

Second World War (1939–1945)

From December 1940 to January 1941, Stalin attended a military conference with all top military officers. The 18th Congress of the CPSU in February 1941 focused on preparing industry and transportation for the war. In early March, Tymoshenko and Zhukov asked him to call up 800,000 reservists, which he initially refused but approved at the end of the month.[15] The size of the Red Army grew from two million in 1938 to over six million in 1941.[16]

On 21 June 1941, a German defector said that Germany would attack the Soviet Union the next night. Stalin alerted all units and told troops to camouflage themselves and their aircraft. He ordered them to secretly occupy firing posts on the border. Germany began bombing border cities at 3:40 a.m. on 22 June, and Stalin met with the Politburo at 4:30. He approved Zhukov's request to immediately attack the enemy, which was sent at 7:15 a.m. On 26 June, Stalin began creating a reserve front 300 kilometers behind the main front.[15]

Joseph Stalin became Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars in 1941, a position he would hold until his death.[17] At the beginning of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union Joseph Stalin was appointed Chairman of the State Defense Committee, People's Commissar of Defense, and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces of the USSR, and remained in these positions until the victorious end of the war. The great victory over the Hitlerite coalition was won by the Soviet people under the leadership of the Communist Party and its Central Committee, headed by Stalin.

Stalin had extensive knowledge of the war situation and demanded exact accuracy from his staff. He required front commanders to send reports every day and criticized Rokossovsky when he did not do so on 16 August 1943. Stalin also had an excellent memory and remembered all the names of over 100 front commanders in addition to many other commanders, members of the People's Commissariat of Defense, and party officials. He personally knew and often convened builders of planes, artillery, and tanks.[18]

During the war, Joseph Stalin, as a head of the Soviet government, took part in the conferences of the leaders of the three powers—the USSR, the USA and Great Britain—in Tehran (1943), in Yalta and Berlin (1945). During these years, Stalin maintained everyday correspondence with the presidents of the USA and the prime-ministers of Great Britain, in which he insistently fought for strengthening of anti-Hitler coalition, consistently defended the national interests of the peoples of the countries which were subject to Hitlerite aggression.

Postwar period and death (1946–1953)

In the postwar period, I. V. Stalin published his works "Marxism and questions of linguistics" (1950) and "Economic problems of socialism in the USSR" (1952), which considers important questions of Marxist-Leninist theory. "The Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR" had a great influence on the development of some positions in the political economy of socialism. I.V. Stalin stressed the objective character of economic laws in socialism; based on the classical Marxism-Leninism statements, he formulated the main economic law of socialism, the law of systematic and proportional development of national economy; noted the importance of priority growth of means of production for the expanded socialist reproduction. At the same time, the work contains a number of erroneous and controversial positions (e.g.: assertion that commodity circulation begins to hinder the development of productive forces of the country and the gradual transition to product exchange is necessary; underestimation of the law of value in production, especially with regard to means of production; the statement about inevitability of reduction of the volume of capitalist production after World War II and about inevitability of wars between capitalist countries in the current conditions).[citation needed]

In October 1952 the 19th Congress of the CPSU was held. At the closing session of the Congress Stalin made a speech. The Plenum of the CPSU Central Committee, which took place after the Congress, elected Joseph Stalin a member of the Presidium of the Central Committee and Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Stalin continued to fight against revisionism and opportunism but underestimated the strength it would have without a capitalist base.[19]

Outstanding work of Stalin was highly appreciated by the Soviet Union. Stalin's outstanding activities were highly appreciated by the Soviet government. He was awarded the ranks of a Hero of Socialist Labor (1939), a Hero of the Soviet Union (1945) and Generalissimo of the Soviet Union (1945). He was awarded with three Orders of Lenin, the Order of Victory, the Order of the Red Banner, Suvorov of the 1st degree and medals.

Death

Stalin's health declined during the early 1950s due to overwork during the war. In the last few months before his death, his security was dismantled. Proskryobychev, Stalin's personal secretary since 1928, was put under house arrest, and Nikolai Vlasik, Stalin's bodyguard, was arrested in December 1952 and died in prison. Pyotr Kosynkin, Vice-Commander of the Kremlin Guard, died of a supposed heart attack on 17 February 1953. Beria was the only one capable of such a plot, and Molotov suspected that MVD chief Beria poisoned Stalin, while Hoxha believed Khrushchev and Mikoyan had planned to assassinate him.

On 1 March 1953, at 23:00 Stalin's guards found him unconscious in his room but did not call a doctor. He did not receive first aid until twelve hours after his collapse and died on 5 March.[19]

Common myths

Antisemitism

While anti-semitism has been a historical tool of the far-right and fascists in particular, "Judeo-Bolshevism" and "cultural bolshevism" being classic fascist conspiracy theories linking the communist movement with fictional Jewish cabals plotting world domination or ethnic domination, some historians still claim that Stalin too was an anti-Semite. While Russia had a long and troubled history with anti-Semitism before revolution, there is no evidence that Stalin held these views. The below letter from Stalin opposes this notion.

In answer to your inquiry:

National and racial chauvinism is a vestige of the misanthropic customs characteristic of the period of cannibalism. Anti-semitism, as an extreme form of racial chauvinism, is the most dangerous vestige of cannibalism.

Anti-semitism is of advantage to the exploiters as a lightning conductor that deflects the blows aimed by the working people at capitalism. Anti-semitism is dangerous for the working people as being a false path that leads them off the right road and lands them in the jungle. Hence Communists, as consistent internationalists, cannot but be irreconcilable, sworn enemies of anti-semitism.

In the U.S.S.R. anti-semitism is punishable with the utmost severity of the law as a phenomenon deeply hostile to the Soviet system. Under U.S.S.R. law active anti-semites are liable to the death penalty.

— J. Stalin, Reply to an inquiry of the Jewish News Agency in the United States [20]

During Stalin's time in office, Jews made up 4.3% of party membership, which was much higher than their share of the total population. Kaganovich and Litvinov, two members of Stalin's leadership, were both Jewish. During the late 1930s, 10% of Central Committee members were Jewish even though only about 1% of the total population was Jewish.[21]

Autocratic rule

Right-wingers and revisionists often claim that Stalin was a dictator who imposed his personal will on the entire country. However, during the Great Patriotic War, the Politburo and military leadership made collective decisions. If they could not agree, they would create a commission of opposing sides to create a proposal. Stalin took others' opinions into account and listened to their advice.[18] The CIA itself admitted in now-declassified documents that the U.S.S.R. always operated under collective leadership, and that Stalin was not the 'dictator' that the Western powers portrayed him to be.[2]

Personality cult

While there is no doubt that Stalin was a revered figure in the USSR, there is no evidence to suggest he made any active efforts to build up a cult of personality around himself. In fact, in 1938 he requested the destruction of a book that portrayed him too positively and stated that the theory of "heroes" was an SR and not a Bolshevik theory.[22] Stalin also condemned the "Great man" in a speech to collective farmers in 1933:

The times have passed when leaders were regarded as the only makers of history, while the workers and peasants were not taken into account. The destinies of nations and of states are now determined, not only by leaders, but primarily and mainly by the vast masses of the working people. The workers and the peasants, who without fuss and noise are building factories and mills, constructing mines and railways, building collective farms and state farms, creating all the values of life, feeding and clothing the whole world—they are the real heroes and the creators of the new life.

— Joseph Stalin, Speech Delivered at the 1st All-Union Congress of Collective Farm Shock Brigadiers, 1933

Popular support

In a poll made in 2019, 70% of Russians said they had a positive view of Stalin's role in history. This was a 12% increase from 58% in 2015.[23]

See also

References

- ↑ “After the conference, in May 1917, a Political Bureau of the Central Committee was instituted, to which Stalin was elected and to which he has been successively re-elected ever since.

[...]

On Lenin's motion, the Plenum of the Central Committee, on April 3, 1922, elected Stalin, Lenin's faithful disciple and associate, General Secretary of the Central Committee, a post at which he has remained ever since.”

Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute (1949). Joseph Stalin: a political biography (pp. 34, 48). [LG] - ↑ 2.0 2.1 “Even in Stalin's time there was collective leadership. The western idea of a dictator within the communist setup is exaggerated. Misunderstandings on that subject are caused by lack of comprehension of the real nature and organization of the Communist power structure.”

"Comments in the Change in Soviet Leadership" (2008-02-26). Central Intelligence Agency. - ↑ “Vissarion, his father, came from the village of Didi-Lilo, near Tiflis, where his parents, like their forebears, had been peasant serfs. For Vissarion emancipation meant that he was free to follow his trade as a cobbler. Around 1870 he moved to Gori, where in 1874 he married Ekaterina Georgievna Geladze, daughter of a serf family from a nearby village. She was about eighteen years of age, some five years younger than her husband. They were humble working people, poor and illiterate.”

Ian Grey (1979). Stalin, man of history (p. 9). [LG] - ↑ “In the autumn of 1888 Stalin entered the church school in Gori, from which, in 1894, he passed to the Orthodox Theological Seminary in Tiflis.

This was a period when, with the development of industrial capitalism and the attendant growth of the working-class movement, Marxism had begun to spread widely throughout Russia. The St. Petersburg League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class, founded and led by Lenin, had given a powerful stimulus to the Social-Democratic movement all over the country.”

Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute (1949). Joseph Stalin: a political biography (p. 5). [LG] - ↑ “I joined the revolutionary movement at the age of fifteen, when I became connected with certain illegal groups of Russian Marxists in Transcaucasia. These groups exerted a great influence on me and instilled in me a taste for illegal Marxian literature.”

Stalin interview with Emil Ludwig (1931). - ↑ “Jn 1896 and 1897, Stalin conduoled Marxist study circles in the seminary, and in August 1898 he formally enrolled as a member of the Tiflis Branch of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. [...]

Stalin worked hard to broaden his knowledge. He studied Capital, the Communist Manifesto and other works of Marx and Engels. He acquainted himself with Lenin's polemical writings against Narodism, "Legal Marxism" and "Economism." His theoretical interests were extremely broad. He studied philosophy, political economy, history and natural science. He read widely in the classics. He thus trained himself to he an educated Marxist. Even at this early date Lenin's writings made a deep impression on him. "I must meet him al all costs," one of Stalin's friends. reports him to have said. after reading an article by Tulin (Lenin).”

Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute (1945). Joseph Stalin: a short biography (p. 5). [LG] - ↑ Joseph Stalin (1939). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The Mensheviks and the Bolsheviks in the Period of the Russo-Japanese War and the First Russian Revolution'. [MIA]

- ↑ Joseph Stalin (1939). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The Mensheviks and the Bolsheviks in the Period of the Stolypin Reaction. The Bolsheviks Constitute Themselves an Independent Marxist Party'. [MIA]

- ↑ Joseph Stalin (1939). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The Bolshevik Party during the New Rise of the Working Class Movement before the First Imperialist War'. [MIA]

- ↑ Joseph Stalin (1939). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The Bolshevik Party in the Period of Preparation and Realization of the October Socialist Revolution'. [MIA]

- ↑ Joseph Stalin (1939). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The Bolshevik Party in the Period of Foreign Military Intervention and Civil War'. [MIA]

- ↑ Joseph Stalin (1939). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The Bolshevik Party in the Period of Transition to the Peaceful Work of Economic Restoration'. [MIA]

- ↑ Joseph Stalin (1939). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The Bolshevik Party in the Struggle for the Collectivization of Agriculture'. [MIA]

- ↑ Joseph Stalin (1939). History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): 'The Bolshevik Party in the Struggle to Complete the Building of the Socialist Society. Introduction of the New Constitution'. [MIA]

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ludo Martens (1996). Another View of Stalin: 'Stalin and the anti-fascist war' (pp. 192–8). [PDF] Editions EPO. ISBN 9782872620814

- ↑ Ludo Martens (1996). Another View of Stalin: 'Socialist industrialization' (pp. 35–42). [PDF] Editions EPO. ISBN 9782872620814

- ↑ Samuel Totten, Paul Bartrop (2008). Dictionary of Genocide: A–L. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313346422

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Ludo Martens (1996). Another View of Stalin: 'Stalin and the anti-fascist war' (pp. 229–236). [PDF] Editions EPO. ISBN 9782872620814

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Ludo Martens (1996). Another View of Stalin: 'From Stalin to Khrushchev' (pp. 253–262). [PDF] Editions EPO. ISBN 9782872620814

- ↑ Stalin: Reply to an inquiry of the Jewish News Agency in the United States MIA link

- ↑ Albert Szymanski (1984). Human Rights in the Soviet Union: 'The European Nationalities in the USSR' (pp. 88–94). [PDF] London: Zed Books Ltd. ISBN 0862320186 [LG]

- ↑ Joseph Stalin (1938). Letter on Publications for Children Directed to the Central Committee of the All Union Communist Youth. London: Red Star Press. [MIA]

- ↑ "Anticommunism Fails: 70% of Russians have a positive opinion on Joseph Stalin" (2019-04-17). In Defense of Communism. Archived from the original on 2021-06-29.

Notes

- ↑ Although some historians claim he was born in 18th December, his birthday was officially celebrated on 21st December.

- ↑ The city of Gori was part of the Tiflis Governorate, which was one of the administrative divisions of the Russian Empire.