More languages

More actions

Verda.Majo (talk | contribs) m (→DPRK) Tag: Visual edit |

Verda.Majo (talk | contribs) m (→DPRK) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

In 2017, sanctions imposed by the UN caused thousands of DPRK workers who had been working abroad to be forced to return to DPRK as well as led to the closure of numerous DPRK companies and joint ventures.<ref>[https://www.asianews.it/news-en/North-Korean-workers-leave-China-because-of-UN-sanctions-41942.html “North Korean Workers Leave China because of UN Sanctions.”] Asianews.it. 2017. [https://web.archive.org/web/20220909073331/https://www.asianews.it/news-en/North-Korean-workers-leave-China-because-of-UN-sanctions-41942.html Archived] 2022-09-09.</ref> | In 2017, sanctions imposed by the UN caused thousands of DPRK workers who had been working abroad to be forced to return to DPRK as well as led to the closure of numerous DPRK companies and joint ventures.<ref>[https://www.asianews.it/news-en/North-Korean-workers-leave-China-because-of-UN-sanctions-41942.html “North Korean Workers Leave China because of UN Sanctions.”] Asianews.it. 2017. [https://web.archive.org/web/20220909073331/https://www.asianews.it/news-en/North-Korean-workers-leave-China-because-of-UN-sanctions-41942.html Archived] 2022-09-09.</ref> | ||

A 2020 zine released by [[Nodutdol]] describes the history of sanctions directed against DPRK in the following way:<blockquote>The first of many generations of US sanctions against the DPRK began shortly after the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, which threatened the US-backed [[Syngman Rhee|Rhee Syngman]] government in the south. Since the beginning of the DPRK nuclear tests in 2003, the [[George W. Bush|Bush]] and [[Barack Obama|Obama]] administrations respectively lifted some sanctions to facilitate negotiations around DPRK denuclearization, and then reinstated them when the negotiations failed to produce the results desired by the US. The sanctions regime reimplemented by the Obama administration targeted three fourths of all DPRK exports, and instituted a labyrinthine network of financial limitations that have functionally cut the DPRK off from accessing international trade or foreign investment. The administrative hurdles placed on international aid organizations and outright bans on items containing metal instituted by Obama’s US and UN sanctions have had devastating effects on the DPRK agricultural, medical, and sanitation systems. In 2018, 3,968 people in the DPRK, who were mostly children under the age of 5, died as a result | A 2020 zine released by [[Nodutdol]] describes the history of sanctions directed against DPRK in the following way:<blockquote>The first of many generations of US sanctions against the DPRK began shortly after the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, which threatened the US-backed [[Syngman Rhee|Rhee Syngman]] government in the south. Since the beginning of the DPRK nuclear tests in 2003, the [[George W. Bush|Bush]] and [[Barack Obama|Obama]] administrations respectively lifted some sanctions to facilitate negotiations around DPRK denuclearization, and then reinstated them when the negotiations failed to produce the results desired by the US. The sanctions regime reimplemented by the Obama administration targeted three fourths of all DPRK exports, and instituted a labyrinthine network of financial limitations that have functionally cut the DPRK off from accessing international trade or foreign investment. The administrative hurdles placed on international aid organizations and outright bans on items containing metal instituted by Obama’s US and UN sanctions have had devastating effects on the DPRK agricultural, medical, and sanitation systems. In 2018, 3,968 people in the DPRK, who were mostly children under the age of 5, died as a result of shortages and delays to UN aid programs caused by sanctions. The [[Donald Trump|Trump]] administration has elaborated on DPRK sanctions by returning the DPRK to the State Sponsors of Terrorism list, targeting the DPRK’s access to international shipping, instituting a travel ban, and adding new measures targeting a number of DPRK industries.<ref>[https://nodutdol.org/sanctions-of-empire/ "제국의 제재 - Sanctions of Empire."] Nodutdol. October 20, 2020. [https://nodutdol.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Sanctions-of-Empire.pdf PDF]. [https://web.archive.org/web/20220520095404/https://nodutdol.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Sanctions-of-Empire.pdf Archive].</ref></blockquote> | ||

Foreign Policy in Focus (FPIF) lists out the sanctions and other punishments placed on DPRK as the following:<blockquote>Economic sanctions against North Korea cover trade, finance, investment, even North Korean workers in foreign countries. The earliest of these were imposed by the United States after the Korean War, when Washington imposed a total trade embargo on North Korea and also froze all North Korean holdings in the United States. In the 1970s, the United States tightened these restrictions by prohibiting the import of any agricultural products that contained raw material from North Korea. The United States also prohibits any exports to North Korea if they contain more than 10 percent of U.S.-sourced inputs. There are some minor humanitarian exemptions to these sanctions. Between 2004 and 2019, in the wake of the failed Agreed Framework of the Clinton era, Congress passed eight bills that further restricted economic and financial interactions with North Korea. | Foreign Policy in Focus (FPIF) lists out the sanctions and other punishments placed on DPRK as the following:<blockquote>Economic sanctions against North Korea cover trade, finance, investment, even North Korean workers in foreign countries. The earliest of these were imposed by the United States after the Korean War, when Washington imposed a total trade embargo on North Korea and also froze all North Korean holdings in the United States. In the 1970s, the United States tightened these restrictions by prohibiting the import of any agricultural products that contained raw material from North Korea. The United States also prohibits any exports to North Korea if they contain more than 10 percent of U.S.-sourced inputs. There are some minor humanitarian exemptions to these sanctions. Between 2004 and 2019, in the wake of the failed Agreed Framework of the Clinton era, Congress passed eight bills that further restricted economic and financial interactions with North Korea. | ||

Revision as of 09:33, 9 September 2022

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by governments against another government, group, or an individual. They are a form of warfare, similar to siege warfare.[1][2] Economic sanctions are also known as embargoes. The stated purpose of sanctions is typically to apply economic pressure on a country, in order to influence the government's decision-making, and is often portrayed as a peaceful alternative to armed conflict. However, the material function of sanctions is to create widespread economic hardship, desperation, and destabilization in the targeted country, typically to pave the way for the overthrow of the government or prevent their economic development.

The outcome of economic sanctions is mass suffering and death amongst the targeted population.[3][4] Often, the suffering and death and economic underdevelopment resulting from the sanctions are then publicized as being inherent to the targeted government's own policies and blamed on the government, and disingenuous human rights investigations are subsequently launched to further isolate and destabilize the country, and even used as a justification for increasing the severity of the sanctions.

An essay posted on Monthly Review Online states that economic sanctions function as undeclared war by creating severe economic disruption and hyperinflation, and explains that because sanctions interfere with the functioning of essential infrastructure i.e. electrical grids, water treatment and distribution facilities, transportation hubs, and communication networks by blocking access to key industrial inputs, such as fuel, raw materials, and replacement parts, they lead to droughts, famines, disease, and abject poverty, which results in the death of millions. Exact numbers are difficult to quantify because no international tally of casualties related to economic sanctions is recorded, which obfuscates its overall fatal impact.[5]

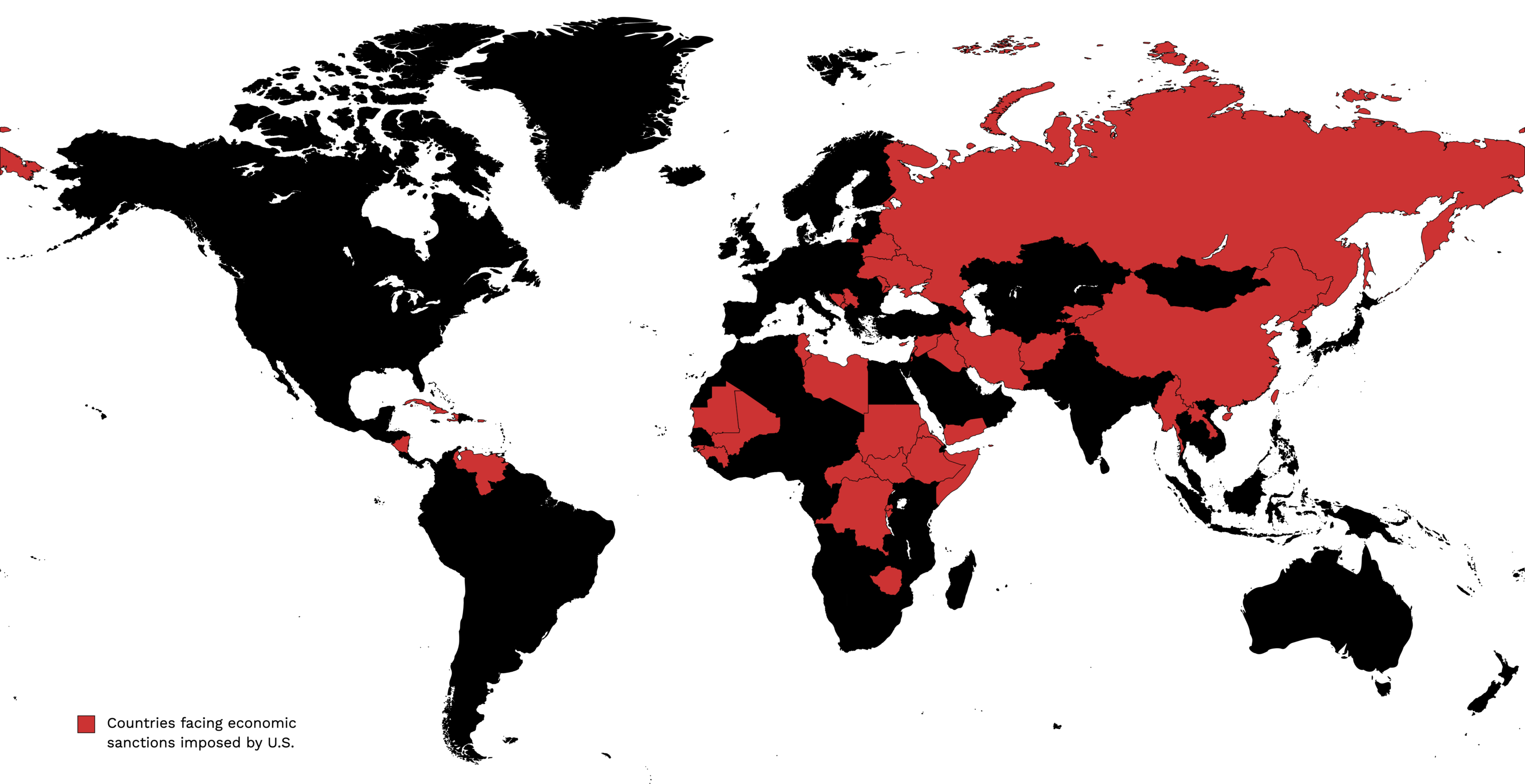

According to a page on the Sanctions Kill website, the countries imposing economic sanctions "are the wealthiest, the most powerful, and the most industrially developed countries in the world. The intention is to choke the economies of poor, developing countries, most of which were formerly colonized. The sanctions, as well as visiting extreme hardship upon the civilian population, are intended to serve as a dire threat to surrounding countries, as they impact the economies of the whole region." Sanctions Kill also noted in 2021 that US sanctions affect a third of humanity with more than 8,000 measures impacting more than 40 countries and that the U.S. far exceeds any other country in the number of countries they have strangled with economic sanctions. Sanctions Kill asserts that in a period of human history when hunger and disease are scientifically solvable, depriving hundreds of millions from getting basic necessities is a crime against humanity.[6]

Lauren Smith notes in Monthly Review Online that it is not unilateral sanctions imposed by the U.S. alone that devastate a targeted country, it is the imposition of secondary sanctions upon foreign third parties that represents the final blow to its economy and people. These measures threaten to cut off foreign countries, governments, companies, financial institutions and individuals from the U.S. financial system if they engage in prohibited transactions with a sanctioned target—irrespective as to whether or not that activity impacts the United States directly.[5]

In times of natural disaster, progressives often call for temporary lifting or easing of sanctions in affected countries. However, as sanctions are a form of warfare that are generally used to purposely cause death and suffering in the targeted countries, natural disasters tend to boost the intended deadly effects of sanctions on the targeted countries' populations, as well as create a window of increased plausible deniability for the aggressor countries responsible for imposing the sanctions, the incentive to ease or remove sanctions is low.

Use for destabilization and overthrow of governments

An example of the rationale behind the use of economic pressure to destabilize and overthrow governments can be found in a 1960 memorandum between U.S. officials under the Secretary of State for Inter-American affairs, discussing obstacles in overthrowing the government of Cuba. The author of the memo notes that "the majority of Cubans support Castro" and that there was "no effective political opposition". In light of there being widespread support for the government and no effective opposition for the U.S. to back and empower, and also noting that "Militant opposition to Castro from without Cuba would only serve his and the communist cause" the author wrote that the "only foreseeable means of alienating internal support" would be "through disenchantment and disaffection based on economic dissatisfaction and hardship" and that "every possible means should be undertaken promptly to weaken the economic life of Cuba" and to "call forth a line of action which, while as adroit and inconspicuous as possible, makes the greatest inroads in denying money and supplies to Cuba, to decrease monetary and real wages, to bring about hunger, desperation and overthrow of government." The U.S. State Department's Office of the Historian notes that the recipient of the memorandum initialed the "yes" option in reply to moving forward with these ideas.[7] This is one example of the logic behind the use of economic pressure to destabilize and overthrow governments, and shows that is an option that may be taken when local support for the government is high and explicit external opposition would create a disadvantageous propaganda situation for the aggressor country and strengthen the resolve of the targeted country, and therefore an "inconspicuous" policy of bringing about hunger and desperation is a preferable avenue of attack.

Kim Ji Ho, author of Understanding Korea: Human Rights, observes the deadly, criminal effects of U.S. sanctions on DPRK's citizens, and writes of their ultimate goal of destabilizing the country with the purpose of overthrowing its system:

The economic sanctions and blockade the US, in collusion with its vassal states, has imposed on the DPRK have been unprecedented in their viciousness and tenacity. These moves are aimed, in essence, at isolating and stifling the country and destabilizing it so as to overthrow its system. The moves the US resorts to by enlisting even its vassal states are a crime against human rights and humanity, which check the sovereign state’s right to development and exert a great negative impact on its people’s enjoying of their rights, a crime as serious as wartime genocide.[8]

Opposition to economic sanctions

Opposition to sanctions can be found among various ideological camps. Even critics and opponents of governments targeted by sanctions frequently point out the ineffectiveness of the sanctioning in achieving their stated goals and point out the disastrous inhumane effects of sanctions on the general population, even if these critics do not draw the conclusion that the disastrous effects are in fact the purpose of the sanctions. For example, correspondent Ryan Cooper of The Week writes of "America's brainless addiction to punitive sanctions regimes" which "virtually never achieve the desired effect and too often inflict pointless suffering on innocents" and which have not achieved "any major U.S. policy goal in this century" giving examples of U.S. sanctions on Iran, Russia, DPRK, and Venezuela all failing to achieve the goals they were said to be implemented for, and refers to U.S. sanctions on Afghanistan as "miserable and useless economic seige". The journalist goes on to describe how sanctions are often used to bolster the image of the politicians who call for and impose them:

As Henry Farrell and Abraham L. Newman write in The New York Times, American imperialists can't resist the temptation to use U.S. control over the dollar funding system to economically strangle perceived adversaries. Presidents use sanctions to signal they're tough by inflicting pain on "enemies" (most often innocent civilians) who are helpless to fight back from thousands of miles away. Presidents don't remove sanctions because that would be "weak," or because the Kafkaesque imperial bureaucracy only goes in one direction, or because it would be humiliating to admit error.[9]

A 2022 article published by the Center for Economic and Policy Research states that economic sanctions have become one of the main tools of US foreign policy, despite little proof of their efficacy, and widespread evidence that they often target civilian populations, with lethal and devastating effects. The article states that though sanctions are a key part of US policy-making, and a defining feature of the global economic order, sanctions, and their human costs, as well as violations of treaties to which the United States is a signatory, receive relatively little attention in most US media outlets.[10]

Sanctions by targeted country

According to Sanctions Kill, US sanctions affect a third of humanity with more than 8,000 measures impacting more than 40 countries and notes that the U.S. far exceeds any other country in the number of countries they have strangled with economic sanctions. The countries listed by Sanctions Kill as being affected by sanctions as of 2022 include the following: Afghanistan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burundi, Central African Republic, China (PR), Comoros, Crimea Region of Ukraine, Cuba, Cyprus, Congo – DR, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Haiti, Iran, Iraq, Korea – DPRK, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Lebanon, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Moldova, Montenegro, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Palestine, Russia, Rwanda, Serbia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, Venezuela, Yemen, and Zimbabwe.[6]

Afghanistan

Since 2021, the U.S. Biden administration has blocked Afghanistan’s central bank from accessing roughly $7 billion in its foreign reserves held in the US. Along with sanctions on government officials and a cutoff of aid, this has contributed to a severe collapse of Afghanistan’s economy.[10]

Cuba

The US embargo of Cuba is one of the oldest and strictest of all US sanctions regimes, prohibiting nearly all trade, travel, and financial transactions since the early 1960s.[10]

U.S. officials have written that creating "disenchantment and disaffection based on economic dissatisfaction and hardship" through denying money and supplies to Cuba would be a method they should pursue in order to "bring about hunger, desperation and overthrow of government" in that country.[7]

In an article for The Guardian, David Adler writes of the embargo on Cuba, that "the US embargo impacts every aspect of life on the island – and that is the precisely the point" and goes on to state that "Both the Biden administration and its Republican opposition claim that these measures are targeted at the regime, rather than the Cuban people. But the evidence to the contrary is not only anecdotal. The UN estimates that the embargo has cost Cuba over $130bn in damages" and says that the embargo "fails the test of its own logic" pointing out that "the Biden administration argued that the embargo aims to 'support the Cuban people in their quest to determine their own future'. But the Biden administration does not dare to explain how making Cuba poorer, sicker and more isolated supports their quest for self-determination."[11]

DPRK

DPRK is one of the most sanctioned countries in the world, and has been subject to sanctions since just after its foundation. The US first imposed sanctions on north Korea during the Korean War in the 1950s. Following the country’s 2006 nuclear test, the US, EU, and others added more stringent sanctions, which have periodically intensified since. Sanctions now target oil imports, and cover most finance and trade, and the country’s key minerals sector.[10]

In 2017, sanctions imposed by the UN caused thousands of DPRK workers who had been working abroad to be forced to return to DPRK as well as led to the closure of numerous DPRK companies and joint ventures.[12]

A 2020 zine released by Nodutdol describes the history of sanctions directed against DPRK in the following way:

The first of many generations of US sanctions against the DPRK began shortly after the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, which threatened the US-backed Rhee Syngman government in the south. Since the beginning of the DPRK nuclear tests in 2003, the Bush and Obama administrations respectively lifted some sanctions to facilitate negotiations around DPRK denuclearization, and then reinstated them when the negotiations failed to produce the results desired by the US. The sanctions regime reimplemented by the Obama administration targeted three fourths of all DPRK exports, and instituted a labyrinthine network of financial limitations that have functionally cut the DPRK off from accessing international trade or foreign investment. The administrative hurdles placed on international aid organizations and outright bans on items containing metal instituted by Obama’s US and UN sanctions have had devastating effects on the DPRK agricultural, medical, and sanitation systems. In 2018, 3,968 people in the DPRK, who were mostly children under the age of 5, died as a result of shortages and delays to UN aid programs caused by sanctions. The Trump administration has elaborated on DPRK sanctions by returning the DPRK to the State Sponsors of Terrorism list, targeting the DPRK’s access to international shipping, instituting a travel ban, and adding new measures targeting a number of DPRK industries.[13]

Foreign Policy in Focus (FPIF) lists out the sanctions and other punishments placed on DPRK as the following:

Economic sanctions against North Korea cover trade, finance, investment, even North Korean workers in foreign countries. The earliest of these were imposed by the United States after the Korean War, when Washington imposed a total trade embargo on North Korea and also froze all North Korean holdings in the United States. In the 1970s, the United States tightened these restrictions by prohibiting the import of any agricultural products that contained raw material from North Korea. The United States also prohibits any exports to North Korea if they contain more than 10 percent of U.S.-sourced inputs. There are some minor humanitarian exemptions to these sanctions. Between 2004 and 2019, in the wake of the failed Agreed Framework of the Clinton era, Congress passed eight bills that further restricted economic and financial interactions with North Korea. On the financial side, the United States has effectively blocked North Korea from participating in the U.S. financial system but more importantly from engaging in any dollar-based transactions. Secondary sanctions target any countries that conduct business with North Korea, which further limits the country’s access to the global economy. Because North Korea remains on the State Sponsors of Terrorism list, it does not enjoy sovereign immunity from prosecution for certain acts such as torture and extrajudicial killing. The United States is further obligated by the stipulations of this regulation to oppose any effort by North Korea to join the IMF or World Bank.[14]

FPIF additionally states that a number of individuals and entities have been singled out for sanctions, from high-level officials and directors of banks to trading and shipping companies to specific vessels and even non-Korean business people. Apart from U.S. sanctions, the UN Security Council has passed "about a dozen" unanimous resolutions that ban trade in arms, luxury goods, electrical equipment, natural gas, and other items. Other sanctions impose a freeze on the assets of designated individuals and entities, prohibit joint ventures with these prohibited entities, and restrict cargo trade with North Korea. Japan has also imposed sanctions, which include measures freeze certain DPRK and Chinese assets, ban bilateral trade with DPRK, restrict the entry of DPRK citizens and ships into Japanese territory, and reportedly prohibit remittances worth more than $880. South Korea, Australia, and the EU also maintain their own sanctions against DPRK.[14]

According to FPIF, sanctions on DPRK have "demonstrably failed." FPIF notes that sanctions didn’t deter DPRK from pursuing a nuclear weapons program, nor have they been subsequently responsible for pushing it toward denuclearization, and adds that DPRK has been under sanctions for nearly its entire existence and it doesn’t have a strong international economic presence that can be penalized, and "has been willing to suffer the effects of isolation in order to build what it considers to be a credible deterrence against foreign attack."[14]

Iran

US sanctions on Iran began during the 1979 hostage crisis, and currently bar US actors — plus some non-US actors — from most all trade and financial transactions with Iran. Though certain sanctions were lifted as a result of the 2015 nuclear deal, the majority have been reimposed since the US’s unilateral withdrawal.[10]

Iraq

When asked about half a million Iraqi children who died due to US sanctions, Madeleine Albright said in 1996, "the price was worth it."[15]

In 2003, President Bush signed an order to take possession of the Iraqi government assets that were frozen in 1990, before the Persian Gulf War. As a result, seventeen of the world’s biggest financial institutions were told by the Treasury Department to hand over $1.7 billion in frozen Iraqi assets that the U.S. government intended to place in an account at the NY Fed.[5]

Libya

In 2015, it was announced that $67 billion in Libya’s assets remained frozen from 2011. In 2018, it was announced that Libya’s assets had decreased to $34 billion. The UN Libya Experts Panel is “looking for answers” to explain the disappearance of $33 billion in frozen assets.[5]

Russia

US-imposed sanctions on Russia targeting the financial, energy, and defense sectors began in 2014 after the annexation of Crimea. This regime was expanded, particularly by the US, UK, and EU, in response to the 2022 conflict in Ukraine, by barring most financial transactions, oil and gas imports, and other activities.[10]

Venezuela

US sanctions on Venezuela began under the Obama administration, and were expanded significantly under Trump, including broad financial sanctions targeting the state oil company and sanctions targeting Venezuelan oil exports, all of which have contributed to the country’s economic collapse.[10]

According to an article in Monthly Review Online, in August 2019, Venezuela’s foreign minister, Jorge Arreaza, stated that the sanctions the United States imposed against it had left more than $3 billion of its assets frozen in the global financial system. Additionally, The Bank of England blocked Venezuela’s attempts to retrieve $1.2 billion worth of gold stored as the nation’s foreign reserves in Britain. It is reported that former national security advisor to President Donald Trump, John Bolton, pressured England to freeze Venezuelan assets. By some estimates, Venezuela holds more than $8 billion in foreign reserves. Additionally, the U.S. froze all the assets Venezuela’s state-owned oil company, PDVSA, has in the United States. While it allows PDVSA’s U.S.-based subsidiary, Citgo, to operate, it confiscates the money it earns and places it in a blocked account.[5]

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov claims that the U.S. simply confiscates Venezuela’s money under the guise of sanctions, noting that the U.S. is experienced in such illegal affairs, giving Iraq, Libya, Iran, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Panama as examples. According to Lavrov, "US companies operating in Venezuela are excluded from the sanctions regime. Simply put they want to overthrow the government and gain profits at the same time."[16]

Zimbabwe

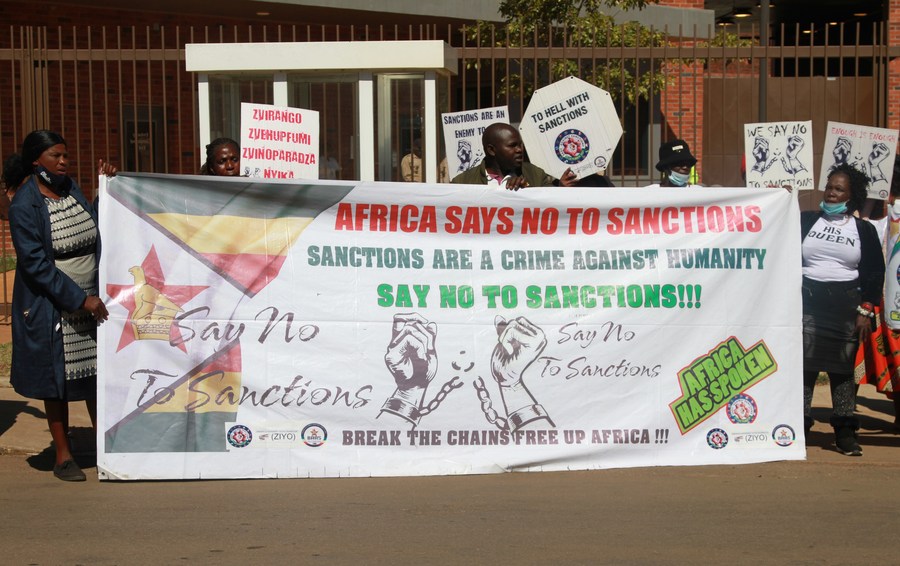

According to a 2022 article by Xinhua News, the U.S. sanctions against Zimbabwe have accumulated since 2001, following a government decision to repossess land from minority white farmers for redistribution to landless indigenous Zimbabweans. The Xinhua article notes that though the Zimbabwean government said the land reform would promote democracy and the economy, "Western countries launched repeated sanctions with little regard for the average person's suffering." Linda Masarira, president of the Labour Economists and Afrikan Democrats (LEAD) political party, said sanctions have been used as a tool of economic warfare against Zimbabwe, and that sanctioning Zimbabwe "was an action that the United States of America decided to do on Zimbabwe to ensure that they make our economy scream, they make things hard for Zimbabweans and imply that black Zimbabweans, native Zimbabweans cannot do their own farming, or run their own economy."[17]

The Broad Alliance Against Sanctions (BAAS) is an organization in Zimbabwe that opposes sanctions. A spokesperson of BAAS was quoted in the Xinhua article regarding the sanctions: "We realized that most industries closed due to sanctions, meaning that sanctions are actually the major cause for all our other problems in Zimbabwe." According to BAAS Chairperson Calvern Chitsunge, officials from the U.S. embassy have tried to bribe the group's four leaders in response to their anti-sanctions activism, noting that the U.S. embassy staff have offered them each 100,000 U.S. dollars, a car and free accommodations at a location of their choosing.[17]

U.S. state officials claim that sanctions target only 83 individuals and 37 entities and denies the Zimbabwean people as the targets. However, there are certain companies that are not allowed to interact or work with Zimbabwean-based companies, such as the U.S.-based company PayPal, causing difficulty for small start-up companies, and Zimbabwe has struggled to build new roads, hospitals, clinics or even rehabilitate old infrastructure because it has been denied access to affordable finance by international institutions. Obert Gutu, member of the National Peace and Reconciliation Commission and former deputy minister of justice and legal affairs said that "Since 2002 when the sanctions were effected, this economy has never been the same again because the most deadly effect of sanctions on Zimbabwe was just to first and foremost paint Zimbabwe as a pariah state."[17]

References

- ↑ Jacob G. Hornberger (2022-03-11). "Sanctions Kill Innocent People and Also Destroy Our Liberty" The Future for Freedom Foundation.

- ↑ Eva Bartlett (2020-04-14). SANCTIONS KILL PEOPLE Popular Resistance, RT.

- ↑ @inspektorbucket on Twitter: "Something to keep in mind: dead children are not an unfortunate side-effect of economic sanctions, but are in fact the goal"

- ↑ Nicholas Mulder. The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Smith, Lauren. “United States Imposed Economic Sanctions: The Big Heist” MR Online. March 10, 2020. Archived 2022-09-08.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 W, Jim. Feb. 2, 2021. “Sanctions Fact Sheet/over 40 Countries | Sanctions Kill.” Sanctionskill.org. Archived 2022-09-07.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Memorandum From the Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs (Mallory) to the Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs (Rubottom)." Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958–1960, Cuba, Volume vi - Office of the Historian. State.gov. U.S. Department of State. Archived 2022-08-14.

- ↑ Kim Ji Ho (2017). Understanding Korea 9: Human Rights. Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

- ↑ Cooper, Ryan. 2022. “Driving Afghanistan to Famine.” The Week. January 12, 2022.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Galant, Michael. “CEPR Sanctions Watch, May-June 2022” Center for Economic and Policy Research. July 8, 2022. Archived 2022-09-07.

- ↑ David Adler (2022-02-03). "Cuba has been under US embargo for 60 years. It’s time for that to end" The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2022-8-14.

- ↑ “North Korean Workers Leave China because of UN Sanctions.” Asianews.it. 2017. Archived 2022-09-09.

- ↑ "제국의 제재 - Sanctions of Empire." Nodutdol. October 20, 2020. PDF. Archive.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Feffer, John. 2021. “The Problem of Sanctions against North Korea.” Foreign Policy in Focus. November 22, 2021. Archived 2022-09-09.

- ↑ @nickwestes on Twitter: "When asked about half a million Iraqi children who died of US sanctions, Madeleine Albright said in 1996, "the price was worth it." The former Secretary of State was never brought to justice. Today, the US sanctions about a third of the world's population."

- ↑ “‘Cynical’ US Sanctions Meant to Confiscate Venezuela’s Assets – Lavrov.” RT International. RT. January 29, 2019. Archived version.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Tichaona Chifamba, Zhang Yuliang, Cao Kai. "Two-decade-old U.S. sanctions leave Zimbabweans suffering, triggering protests". Xinhua. 2022-07-11. Archived 2022-09-09.