More languages

More actions

| Korea 조선 | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

| |

| Capital | Pyongyang |

| Largest city | Seoul |

| Official languages | Korean |

| Area | |

• Total | 223,155 km² |

| Population | |

• 2017 estimate | 77,000,000 |

Korea is a nation in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula and nearby islands, including the island of Jeju. In the present day, Korea is split between two governments, one located in the north and the other in the south. The Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), commonly called North Korea, is located in the northern portion of the peninsula. Meanwhile, the US-occupied Republic of Korea (ROK), commonly called South Korea, is located in the southern portion of the peninsula. The division of the peninsula in 1945 was originally meant only to be temporary, but has persisted to the present day due to the continued occupation of the south and uncompromising policy of aggression toward the DPRK by the United States.

The DPRK's Minister of Foreign Affairs has stated to the UN General Assembly that the essence of the situation of the Korean peninsula is a confrontation between the DPRK and the US, where the DPRK tries to defend its national dignity and sovereignty against the hostile policy and nuclear threats of the US, and clarified that the DPRK "do[es] not have any intention at all to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against the countries that do not join in the U.S. military actions against the DPRK."[1]

The People's Democracy Party (PDP), a revolutionary workers' party in south Korea, has stated that the Korean reunification and peace struggle is contingent on the withdrawal of U.S. troops, that the U.S. troops are "occupation forces in South Corea and invading army to North Corea" and therefore U.S. military withdrawal from south Korea is "the most desperate and preferred struggle task for the whole Korean nation to solve." The PDP added that as long as the U.S. troops are stationed in south Korea and war exercises are conducted against north Korea, "the prospect for peace is bound to be dark."[2]

The Korean Peninsula is bordered by China to the northwest and Russia to the northeast. It is separated from Japan to the east by the Korea Strait and the Sea of Japan (East Sea).

Etymology[edit | edit source]

The English name "Korea" derives from the Korean kingdom of Goryeo, also transcribed as Koryŏ (Korean: 고려), which lasted from 918 to 1392. It is commonly considered that during the Goryeo period, the individual identities of Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla were successfully merged into a single entity that became the basis of modern-day Korean identity.

In the modern Korean language, the word used to refer to Korea differs in usage between DPRK and the south. In DPRK, Korea is referred to as Choson (Korean: 조선; Hanja: 朝鮮), while in the south, Korea is referred to as Hanguk (Korean: 한국; Hanja: 韓國). Each of these names has roots in both modern and ancient Korean history.[3] Therefore, among the liberation movement in Korea during the imperial Japanese occupation period, the names Choson and Hanguk both came to be regarded as potential choices for the future name of the post-liberation country.

In south Korea, it is common to refer to DPRK as "Bukhan" (북한; 北韓), meaning "North Han (Korea)". Meanwhile, it is common for people in DPRK to refer to south Korea as "Namchoson" (남조선; 南朝鮮), "South Choson (Korea)". In some contexts, the word cheuk (측; 側), meaning "side" is used, forming bukcheuk, "north side" and namcheuk, "south side", to speak more neutrally about each other.[4]

The name Choson derives from a Korean dynasty which ruled from 1392 to 1897. However, in October of 1897, the monarch of Korea declared an end to the Choson Kingdom, founding a new regime known as the Daehanjeguk or "Great Han Empire" (Korean: 대한제국; Hanja: 大韓帝國) in 1897, with himself as emperor. The name "Daehan" was formed in reference to the three states that existed in Korea in the past, Mahan, Byunhan, and Jinhan. However, with the Japanese annexation of Korea in 1910, the name for Korea was reverted back to "Choson" during the period of Japanese imperialism.[5]

Therefore, an argument emerged that the future name of the country should be "Daehan" (Korean: 대한; Hanja: 大韓) as it had been the name of the country just prior to the Japanese colonial period, and "Choson" had been the name revived by the Japanese. However, the independence movement activists affiliated with socialism preferred "Choson" to "Daehan" because, for the general public, the name Choson was a more familiar country name than "Daehan Empire" which had only lasted for about 10 years, and "Daehan" was the name of the country that fell to Japanese annexation, making it an undesirable name.[5]

Eventually, the government that formed in south Korea came to be called Daehanminguk (Korean: 대한민국; Hanja: 大韓民國), which literally means “The Great Han Republic”, or, since “Han” here refers to Korea, “The Great Korean Republic”, with the name Hanguk being a short version of this name. Meanwhile in north Korea, people continued using Choson, the word for Korea that had been used during the early 20th century Japanese colonial period and the 14th – 19th century Choson Dynasty.[6]

History[edit | edit source]

Prehistory[edit | edit source]

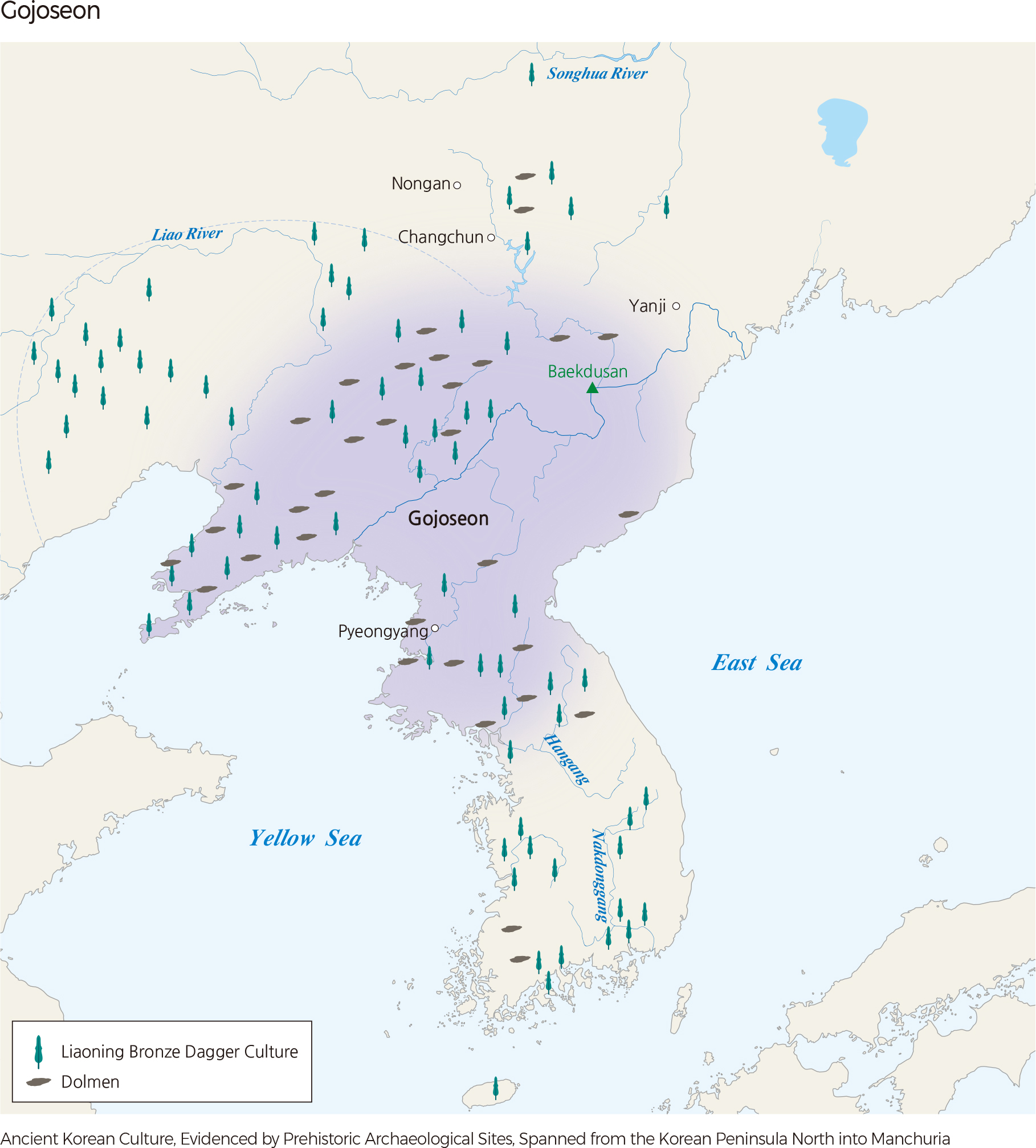

The prehistory of the Korean nation began with human settlement in Manchuria and the Korean Peninsula approximately 700,000 years ago. In the Paleolithic Age, the early inhabitants of the land survived by hunting and gathering. Korea's Neolithic Age began around 8,000 BCE. People began farming, cultivating cereals, using polished stone tools, and creating distinctive comb-patterned pottery. People of this age began to settle permanently and formed clan societies. The Bronze Age of the Korean Peninsula began around the 10th century BCE, while it began around the 15th century BCE in Manchuria. During this age, the clan societies began to merge under influential leaders and they gradually developed into early states.[8]

Gojoseon[edit | edit source]

Gojoseon, or Kochoson (Korean: 고조선; Hanja: 古朝鮮), is regarded as the first state of the Korean people, and is considered to have been established in 2333 BCE and lasted until 108 BCE.[8][9][7] Though called Joseon (Choson), it is referred to in modern times as "Gojoseon" ("Kochoson") in order to distinguish it from the later Joseon (Choson) Dynasty (1392-1910).[10]

Korea's predominant foundation myth consists of the legend of Dangun (Korean: 단군), who is considered to be the founder of Korea. According to the narrative, he is the son of a heavenly prince who wanted to live on earth, and a bear who became a human woman. Dangun is considered to have established his capital in the city of Pyongyang (later moving it to Asadal, or originally establishing it in Asadal by some accounts)[11] and called his kingdom Joseon, and is considered to have ruled for 1,500 years, then became a mountain god.[9] In both north and south Korea, National Foundation Day (Korean: 개천절; Hanja: 開天節; lit. "opening of heavens celebration" or "the day the sky opened") is observed on October 3, marking the founding of Korea by Dangun.[12] According to an article on south Korea's Ministry of Culture website, "despite inconsistencies between historical accounts, ultimately Dangun is still considered the founder of this nation."[11]

Over time, Gojoseon adopted Iron Age culture, developing in agriculture, handicrafts, and military strength. It engaged as an intermediary in trade with China, shipping items such as leather, clothes and fur goods.[9] However, a confrontation developed between Gojoseon and China's Han Dynasty, with the Han attacking Gojoseon, with ground and naval forces. Initially, these attacks were repelled and Gojoseon was able to defend its capital. However, the Han reinvaded with a greater force, and after a year of war, the capital fell and Gojoseon collapsed in 108 BCE.[8][9]

Three Kingdoms and other states[edit | edit source]

Toward the end of the Gojoseon period and after its fall in 108 BCE, various other states and groups of states were developing on the Korean Peninsula and Manchuria. Among them were states such as Buyeo, Dongye, Okjeo, and the Three Han States (Korean: 삼한; Hanja: 三韓) of Mahan, Jinhan, and Byeonhan.[7] Buyeo, located in Manchuria, was eventually incorporated into the rising feudal state of Goguryeo (Koguryo).[9][13] Over time, the states of Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla developed and gained power in their respective locations throughout Manchuria and the Korean Peninsula, with this period commonly referred to as the Three Kingdoms Period.[7][13] Other notable states existing in this time were the Gaya confederacy, which was located between Baekje and Silla and conquered by Silla in 562 CE,[14] and Tamna, a kingdom located on Jeju Island.[15]

King Tongmyong established the Koguryŏ Kingdom (37 BCE–668 CE).[16]

The first unified Korean state was the Koryŏ Kingdom, which existed from 918 to 1392. By then, Buddhism was already widespread in Korea. In the early 13th century, Korea suffered a foreign invasion.[17]

Joseon dynasty[edit | edit source]

The Joseon dynasty was founded in 1392 and lasted until 1897, a period of just over 500 years. It was followed by the relatively short-lived Korean Empire (1897-1910), which ended with the Japanese colonial period.

The government and public systems of the Joseon dynasty were organized according to principles of Neo-Confucianism, the official state ideology. Unlike the Goryeo dynasty, in which agricultural lands were privately controlled by aristocrats and local clans, the Joseon dynasty installed a centralized government that was responsible for overseeing the legal administration, the military, and the performance of national rituals.[18]

Early and middle Joseon period[edit | edit source]

Sejong, the fourth king of the feudal Joseon dynasty, invented the Korean writing system in 1444.[19] Koreans had used the traditional Chinese characters for a writing system for many centuries. The invention of the Korean writing system contributed to increasing literacy and enhancing communication between the people and the government.[20] In the modern day, the Korean writing system's invention is commemorated throughout Korea on Korean Alphabet Day, observed in north Korea on January 15th (the day the alphabet was created) and in south Korea on October 9 (the day the alphabet was proclaimed).[21]

Joseon maintained friendly relations with the Ming dynasty of China. The two countries exchanged royal envoys every year and engaged in cultural and economic exchanges. Joseon also accepted Japan's request for bilateral trade by opening the ports of Busan, Jinhae, and Ulsan. In 1443, Joseon signed the Gyehae Treaty with the clan of Tsushima Island for limited bilateral trade. Joseon also traded with other Asian countries such as Ryukyu, Siam, and Java. Throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, Joseon maintained good relations with Japan. However, in the 16th century, Japan called for a larger share of the bilateral trade, but Joseon refused to comply with the request, resulting in a war that lasted for 7 years, referred to as the Japanese invasions of Korea of 1592–1598 or the Imjin War.[20]

Jong Mun-bu's volunteer army defeated Japanese pirates invading northern Korea in the 16th century.[22]

Late Joseon period[edit | edit source]

By the mid-19th century, the western powers had forced the Qing dynasty of China and Japan to open their doors and then asked the same of Joseon, but Joseon rejected such requests, facing naval attacks by the French in 1866 and by the USA in 1871, as well as by Japan in 1875.[23]

In 1866, a criminal intrusion into Korea's Taedong River by the USA's ship General Sherman occurred, an example of gunboat diplomacy. Demanding "trade" and refusing to leave, the General Sherman's crew perpetrated theft, violence, and kidnapping and killing of Koreans until Pyongyang citizens finally were able to set the boat on fire and sink it. This incident was followed by other incidents with the USA's naval vessels continuing to intrude into Korean territory as well as conducting illegal gold prospecting in Korea.[24]

Joseon was forced to sign an unequal treaty with Japan in 1876 under military threat.[23]

A Korea-US treaty was made in 1882. As described in Origin of the Korean Question, after the US won numerous privileges via the treaty, "the US moved to reduce Korea to its commodity market, a source of precious metals and other raw materials, and an object of capital investment."[24] After the opening of Korea-US trade in 1883, "American capitalists brought surplus goods like old firearms, petroleum, tobacco and drops to sell them at exorbitant prices [...] And they purchased Korea's precious metals including gold and silver at dirt cheap prices."[24]

Throughout the 1800s, a series of peasant rebellions arose throughout Korea, reflecting the economic and social problems experienced by the peasantry. Additionally, in the 1860s, the ideology of Donghak (Korean: 동학; "Eastern learning") was developed and gained a following among academics. Donghak ideology was characterized by egalitarian tendencies and reflected an anxiety about the looming threat of western aggression, and displayed a reformist attitude toward the prevailing Confucian ideology and governance of Joseon. Donghak ideology and leaders had an influence on subsequent peasant uprisings, although the uprisings were ultimately driven by the peasantry's own impetus.[25]

The Peasant Revolution of 1894, also called the Kabo Peasants' War (Korean: 갑오농민전쟁) or the Donghak Peasant Revolution (Korean: 동학농민혁명), was noteworthy in that it passed beyond the previous sporadic protests at the county and prefecture levels and reached the national level, resulting in an approximately year-long, nation-wide rebellion. The experience of the rebellion had extensive influence on the course of Korea's modern development and the people's consciousness, influencing the March 1st independence movement and the anti-Japanese armed struggle which developed in the following decades.[26] The Donghak ideology would go on to form the basis of Chondoism (Korean: 천도교), a religion espoused in both north and south Korea today and the religion of DPRK's Chondoist Chongu Party (Korean: 천도교청우당), one of the three parties in DPRK's Supreme People's Assembly.[27]

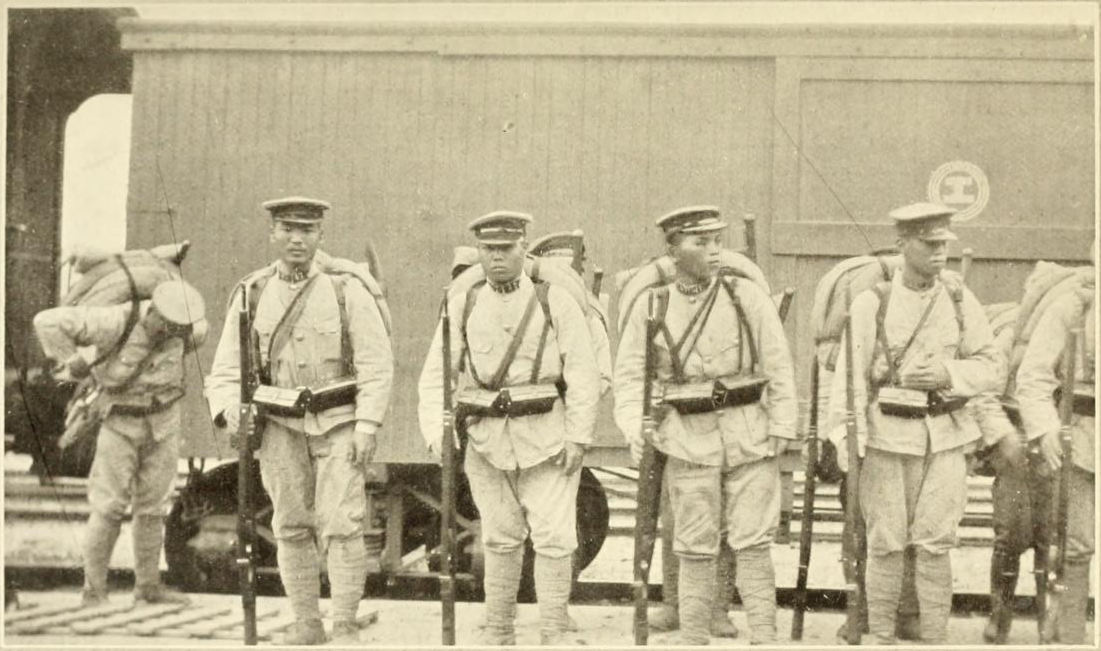

The First Sino-Japanese War (Korean: 청일 전쟁; Hanja: 淸日戰爭), a conflict between the Qing Dynasty and the Empire of Japan from 1894–1895, grew out of conflict between the two countries for supremacy in Korea at the time, with the war being declared after a series of escalating tensions, including the Donghak Peasant Rebellion which saw the Joseon government request the Qing government's assistance to suppress the rebels. The arrival of the Chinese troops in Korea caused the Japanese to send 8,000 troops of their own to Korea, as they considered this to be a violation of their agreements with China in regard to Korea.[28]

As explained by Ryo Sung Chol in the work Korea -- The 38th Parallel North, the USA was the first Western state which set up diplomatic relations with the feudal Korean kingdom, and King Kojong, alarmed by the increasing threats of Japanese imperialism, sent emissaries to Washington twice, in 1896 and 1905, requesting Statesian assistance, in accordance with the duty the US had assumed under an 1882 Korea-US Treaty. The USA and Japan made a secret agreement dividing Korea and the Philippines between themselves, known as the Katsura-Taft Agreement. The USA, Britain and other Western powers at one time pursued the strategy of alliance with Japan, from the ulterior motive of backing, encouraging and using the bellicose Japanese militarist forces as a deterrent to the rapidly growing national liberation forces and the influence of communism in Asia, but that their alliance was fraught with contradictions due to their competing colonial interests.[29]

Over time, imperialist powers vied with each other to pillage Joseon's resources, and in 1897, Joseon changed its name to the Korean Empire and pushed ahead with reforms and an open-door policy. Japan soon won major victories in its wars against the Qing dynasty and Russia, emerged as a strong power in Northeast Asia, and took steps to annex Joseon. Many Koreans resisted this, but in August 1910, the Korean Empire was formally annexed by the Empire of Japan.[23]

Japanese colonialism[edit | edit source]

In 1894, China and Japan went to war over control of Korea. The Japanese established a military base in the Korean capital city of Hanseong (now Seoul) and murdered Empress Myeongseong, who had sought Russian protection against the Japanese. In 1896, Japan offered to divide Korea with Russia along the 38th parallel, the same line along which the U.S. imperialists later split Korea after Japan's defeat in 1945. Russia rejected the proposal along with another proposal giving Manchuria to Russia and Korea to Japan. After negotiations failed, the Japanese attacked a Russian fleet at Port Arthur and took control of Korea in 1905. The Japanese killed 29,000 Korean rebels in the first three years of occupation and disbanded the Korean army in 1907. After the first few years of colonial rule, most of the resistance fighters fled to Manchuria. Japan formally annexed Korea in 1910.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Korea had been developing capitalist elements which were gradually growing and coming into conflict with the feudal system. The feudal ruling circles had been making efforts to prevent the feudal relations from being broken and to prevent the development of capitalist elements. From this process, a socio-political movement to oppose the feudal system and introduce a capitalist system gained in strength. However, Korea's internal development toward capitalism was affected by the imposition of Japanese colonial rule. The Japanese imperialist policies toward Korea altered Korea's development, developing it into a semi-feudal colony that was made into a source of raw materials and labor for imperialist Japan, as well as a market for Japanese commodities and capital investment and a military base for further incursion into the continent.[30]

The Japanese developed Korea's economy for their own purposes, and 60% of Korean rice was exported to Japan. The land that remained under Korean ownership was controlled by feudal landlords who later became the south Korean bourgeoisie. All industrial goods made in Korea were exported to Japan, and Japanese workers were paid three times as much as Koreans. The Japanese sent one eighth of the Korean population to other parts of their empire to work as slaves.[31]

The industrial development of Korea under Japanese rule was geared toward generating colonial superprofits, securing exclusive possession of all the key branches of industry and putting a curb on the development of Korean national industry. As is noted by Kim Han Gil in Modern History of Korea, during the colonial period, Korean industry developed as an "appendage" to Japanese industry, with Korean capitalist forces remaining relatively small, and with traditional handicrafts brought to total ruin:

Korean industry was made to turn out mainly raw materials and half-finished goods for Japanese industry and the productive forces were so distributed as to facilitate their colonial plunder. Korean industry was nothing more than an appendage to Japanese industry.

The Japanese imperialists' policy of monopolizing industries arrested the normal development of national industry. Factories and enterprises run by Koreans were few and most of them were small.

Tyrannical Japanese imperialist colonial rule not only hindered the normal development of national industry but brought the traditional handicraft to total ruin.

Such being the situation, the Korean capitalist forces were very weak in general, and, on top of it, they were split into compradore and non-compradore capitalists.[30]

Korea's comprador capitalists were made up of comparatively big capitalists who were in collusion with the Japanese imperialists and rendering active support to them, along with other reactionary groups such as landlords. Non-comprador capitalists were mainly composed of middle and small entrepreneurs, who typically felt themselves under the thumb of the Japanese imperialists and comprador capitalists and therefore were discontent with Japanese imperialist colonial rule. In addition, the urban small-propertied class found themselves in a precarious situation, due to the predatory policy of the Japanese imperialists and the pressure exercised by the comprador capitalists, causing them constant insecurity. Hence, most of them were also opposed to Japanese imperialism.[30]

In the countryside, the Japanese imperialists left the feudal land ownership and tenancy system in place, but introduced commodity-money relations and modern trade connections, turning it into a semi-feudal system. This enabled them to plunder the countryside through means of both feudal and capitalist exploitation. In addition to this, they seized large amounts of land. By 1927, the absolute majority of the big landlords were Japanese, accounting for 81% of the landlords owning over 200 hectares of land. Landlords exacted farm rent amounting to 50 to 90% of the total output from the peasants and had tenant farmers pay various taxes and levies. Landless and "landshort" peasants constituted the majority of the peasantry, with rich peasants being relatively few in number. The combined colonial, feudal, and capitalist oppression converging upon the peasantry caused high anti-Japanese and anti-feudal sentiments among them, leading them to take an active part in the anti-imperialist, anti-feudal struggle.[30]

Labor conditions under colonial rule saw most workers working for 12 hours or more every day, with many forced to work 14 to 16 hours, while receiving wages consisting of less than half or one-third of those paid to Japanese workers. Due to the peasantry suffering from increasing impoverishment from the colonial policies imposed in the countryside, more and more of them flowed to towns looking for work. Therefore, capitalists could easily obtain cheap labor, which contributed to wages being low. Workers found it hard to meet their minimum expenses and were also charged with various fines. Female and child labor became subject to especially harsh exploitation. Labor protections were absent and workers' concerns were suppressed. When a worker was disabled by a labor accident, they were discharged immediately without compensation.[30]

Additionally, under Japanese rule, all Korean political organizations were banned. Koreans were forced to speak Japanese, have Japanese names, and follow Shintoism.[31] Patriotic Groups (Korean: 애국반; Hanja: 愛國班) were neighborhood cells which functioned as the local arm of the Korean Federation of National Power, the single ruling party of colonial Korea. They typically consisted of groups of 10 households led by a Patriotic Group leader, who would monitor and control others within the Patriotic Group. This included rationing food and goods, enforcing mandatory State Shinto prayer times and shrine visits, "volunteering" laborers upon the colonial government’s request, arranging marriages, holding mandatory Japanese language classes, and spying on "ideological criminals". Patriotic Group leaders were among the first to be targeted for reprisals following Korean Independence in August 1945, with many of their homes set on fire.[33][34][35]

In 1937, Kim Il Sung summarized the conditions experienced by Koreans during the 27 years of occupation and under the intensifying repressive wartime conditions:

Twenty-seven years have elapsed since the Japanese imperialists occupied Korea.

During this period they have turned our country into a source of raw materials and labour, a market for their commodities and a military base for aggression against the continent.

Owing to their ferocious colonial policy, the Korean people have been deprived of their national rights and freedom and are suffering untold sorrow as a ruined people. Our people are not only subjected to double and treble oppression and exploitation by the Japanese imperialists and their lackeys in a manner reminiscent of mediaeval times, but threatened with the danger of being deprived of their beautiful written and spoken language.

The Sino-Japanese War unleashed by the Japanese imperialists is driving our people into an even more terrible plight. With an eye to ensuring "safety in the rear," the Japanese imperialists have greatly expanded their fascist, colonial, repressive machinery-troops, police, prisons, gallows and all-and concocted a new set of Draconian laws. In this way, they have turned our beautiful land of 3,000 ri into a living hell on earth. They are cracking down on the revolutionary forces with fury, while suppressing and slaughtering innocent people as never before. [...]They have openly instituted compulsory conscription and grain deliveries in order to meet the ever-increasing demand for manpower and materials in their aggressive war against the continent. Thus, our precious young and middle-aged people are being forcibly rounded up to become bullet shields for the Japanese imperialists and our country’s abundant natural wealth is being ruthlessly plundered.[36]

Analyzing the conditions at the time, Kim Il Sung described Korea as a semi-feudal colonial society where, due to Japanese colonialist rule, capitalist development was extremely backward and feudal relations of production were predominant. With such conditions, he evaluated that the basic tasks of the Korea revolution at the time were to carry out the task of anti-imperialist national liberation to overthrow Japanese colonial rule, while at the same time, carrying out and anti-feudal democratic revolution to eliminate feudal relations and pave the way for the country's development along democratic lines. Stressing the interrelation of these tasks, he wrote: "Japanese imperialism maintains its colonial system of rule in Korea with the help of its agents, the comprador capitalists and the feudal landlords, and the landlords retain the feudal relations of exploitation under its patronage. Therefore, the struggle against Japanese imperialism and the struggle against feudalism must be waged as an integral whole." Thus he regarded that the task of Korean communists at the time was carrying out an anti-imperialist anti-feudal democratic revolution, regarding these as prerequisites for national and class liberation and social progress, regarding the broad anti-imperialist democratic forces as the motive force of the revolution at that stage. Although the anti-imperialist struggle was broad and would include the peasantry, petty bourgeoisie, and national capitalists, the working class was regarded as being the leading class for the anti-imperialist anti-feudal democratic revolution and in the future socialist revolution and the period of building socialism and communism.[36]

Struggle for independence[edit | edit source]

Koreans engaged in persistent struggles to regain their independence, including armed struggle against the Japanese. They organized numerous clandestine organizations to fight the Japanese. In March 1919, Korean leaders announced the Declaration of Independence. This is known as the March 1st Movement.[37]

The revolutionary tradition of the anti-Japanese struggle still has heavy influence on DPRK's guiding ideology today. The anti-Japanese struggle influenced the development of the Juche idea and is intimately linked with the history of Korean socialism, the Korean independence movement, and the life of Kim Il-sung. Therefore, the revolutionary tradition of the anti-Japanese struggle remains important in the DPRK, as both a source of inspiration as well as important material for study.[38]

In 1926, Kim Il Sung and other communist youths formed the Down-with-Imperialism Union, which set as its immediate task the destruction of Japanese imperialism and achievement of Korea's liberation and independence, with the ultimate aim of building socialism and communism in Korea and destroying all imperialists and building communism throughout the world. By August of 1927 the DIU was reorganized into the Anti-Imperialist Youth League (AIYL) and the Young Communist League of Korea (YCLK). Conducting students' strikes, students' and popular masses' struggle to boycott Japanese goods and their struggle against the Japanese imperialists, they gradually grew into a leading force of the Korean communist movement and the anti-Japanese revolutionary struggle. By 1930, amid a context of strikes, demonstrations, and sporadic violent struggle of workers, peasants, and student youth, Kim Il Sung defined the armed struggle as the main form of struggle necessary to further develop the anti-Japanese struggle.[30]

At a meeting in 1930, Kim Il-sung established the line and strategy of the anti-Japanese revolution and argued that national liberation can be achieved only when all Koreans emerge under the banner of organized armed struggle. Kim Il-sung criticized the existing anti-Japanese movement at the time for the fact that some of the upper classes were only studying words and fighting, and were alienated from the masses.[38] Subsequently, on July 6, 1930, the first unit of the Korean Revolutionary Army (KRA) was formed with the core members of the AIYL and YCLK.[30]

Those recruited into the KRA were tempered through mass struggles, and upon joining the KRA, were trained politically to be communists in addition to being trained militarily. Small groups of KRA members would be formed and sent to various urban and rural areas where they would conduct political and military activities in preparation of forming a guerrilla army. Schools and mass organizations were set up to help educate, rally, and organize the peasant masses, with KRA members taking an active part in the work. The youth who graduated from these schools were sent to different rural areas to conduct organizational and political work for the revolutionization of the rural areas.

In March 1932, Kim II Sung formed a small guerrilla unit with those active in the revolutionary struggle since the DIU as its core and gradually expanded its ranks, while giving general guidance to the work of forming guerrilla ranks in different parts. In the areas along the Tuman River in east Manchuria, small guerrilla units and groups were formed with KRA members and other young communists, workers, peasants and youths who had gained experience in the struggle. Modern History of Korea notes that the struggle to obtain arms was very arduous, stating that "at times a pistol, a bullet or a gram of gunpowder cost human lives. Members of small guerrilla groups, the YCLK, the Anti-Imperialist Youth League, the Children's Vanguard and the Women's Association, and even children and old people took part in the struggle. By their self-sacrificing struggle they took weapons from the Japanese imperialist army of aggression, the Japanese and Manchurian police and the vicious pro-Japanese landlords and officials." Additionally, revolutionaries manufactured weapons themselves using the basic tools and materials they had available to them.[30]

The Anti-Japanese People's Guerrilla Army (AJPGA) was formed on April 25, 1932. Modern History of Korea notes that it was not only an armed force fighting Japanese imperialism, but was also a political army, a propagandist and organizer that educated the masses and roused them to revolutionary struggle. Its founding marked the declaration of war upon the Japanese imperialists as well as signaled a repudiation of the movements within Korea who had sought outside assistance for Korea's national liberation.[30]

A struggle was also waged to establish guerrilla bases, as, with no state backing or outside help, a base was needed to make it possible to organize and conduct military and political activity and logistical work as a whole. A base was also considered necessary in order to progress with preparations for the founding of a communist party and the revolutionary movement as a whole, while waging armed struggle. A policy of setting up bases in the form of a liberated area was adopted. The mountainous area along the Tuman River was determined as the most suitable site, and a struggle was fought there to establish a liberated area, beginning with politico-ideological work being conducted among the masses to raise their anti-imperialist revolutionary consciousness and the expansion of revolutionary organizations into the area, and ties were formed between the people and the guerrilla units. The creation of a guerrilla base was promoted and guerrilla units active in different areas engaged he enemy forces, in cooperation with paramilitary organizations, to neutralize the enemy militarily, leading eventually to a wide area along the Tuman River being secured. Patriotic-minded people began coming to the area and a revolutionary government was established, with barracks, schools, publishing houses, arms repair shops, sewing shops and others being set up in the liberated areas.[30]

The Battle of Pochonbo is an important battle in the history of the liberation of Korea from Japanese occupation. The battle was fought from 3-4 June 1937 by a unit from the guerilla army, who crossed into Korea from China, crept through the forests, rested beside Samjiyon Lake before starting their final advance. Kim Il-sung became a wanted man to the Japanese after the battle, and a hero to the resistance movement and to Korean patriots.[39]

The Red Army entered Korea on 8 August 1948 and continued fighting until the Japanese surrendered on 15 August. US forces did not arrive in Korea until 8 September.[40]

According to the blog Exposing Imperial Japan, which translates Japanese colonial era news articles, the 1000+ Shinto shrines that were built in colonial Korea were all destroyed following Japan's surrender, starting with the Pyongyang shrine which was set on fire on August 15, 1945, the day Imperial Japan surrendered. A statue of Kim Il-sung now stands on the former site of Pyongyang shrine.[41]

Division into north and south[edit | edit source]

After the surrender of the Japanese empire at the end of the Second World War, Korea was divided as a temporary measure by the outside powers of the United States and Soviet Union to assist in the transition away from Japanese colonial rule and the re-establishment of Korea's independence. The line was agreed upon between the Soviet Union and the United States only as a temporary boundary of military operations, and never as a line for the division of Korea.

The United States did not liberate south Korea from Japanese colonial forces, but rather ordered the Japanese forces to remain in place until the U.S. Army landed in Korea nearly a month later.[42] Upon arriving in south Korea, the U.S. forces immediately began dismantling Korean people's committees and placing property back into the hands of Japanese collaborators and re-appointing Japanese collaborators as police, who helped to arrest and dismantle the people's committees. The U.S. occupation forces also struck down the food supply management system of the people's committees, demanding a "free market" of rice. As a result, landlords, police, other government officials, and businessmen engaged in hoarding and speculation and selling the grain to Japan on the black market, causing food shortages and hunger in cities. As the situation continued, U.S. rice rations eventually fell to half of the ration size that had been received under the Japanese colonial administration during World War II, and newspapers published accounts of famine and starvation, further disaster only being averted by eventual shipments of U.S. grains as emergency relief. By 1946, the deteriorating food situation forced the Americans to revive the old Japanese rice collection system, which resulted in farmers being arrested and beaten for not meeting their quotas.[43]

In the northern zone, the Soviets allowed Koreans to govern themselves through a system of people's committees, and assisted Koreans with the re-appropriation of land from Japanese colonizers. The Soviets then left after three years of assisting north Korea in this way.[42] In the south, General Douglas MacArthur ruled as a dictator and established English as the official language.

While the Soviets left Korea in late 1948,[40] the United States failed to withdraw its troops from the south and instead promoted the installation of a pro-US, right wing regime rather than promoting the reunification of Korea. This resulted in opposition among the southern masses, the Jeju uprising and massacre, the escalation of the Korean War, and the continued division of the Korean nation and continued occupation of the south by US forces which persists to the present day.

In the words of author Ryo Sung Chol, "The strife among the great powers for hegemony in the world in the complicated military and political situation towards the close of World War II forced the tragedy of national split upon the Korean people before their rejoicing over liberation subsided."[29]

On February 20, 1948, the day after the US-led UN proposition of the resolution on the US-sponsored separate election in the south, the Central Committee of the Democratic National United Front of North Korea made public its appeal to the entire Korean people at its 24th conference. The appeal indicated that it was clear what kind of election would take place in south Korea, where democratic parties and organizations had been forced underground and democrats were being arrested, imprisoned, tortured and murdered, and called for a general election across the whole of Korea after the withdrawal of the foreign armies. It called for holding elections to the People’s Assembly throughout Korea by secret ballot on the principles of universal, direct and equal vote. The People’s Assembly elected in that way would approve the constitution and establish a democratic government, and Kim Il Sung put forward the line of convening a joint conference of political parties and social organizations of north and south Korea.[29]

Establishment of DPRK and ROK[edit | edit source]

Faced with the serious menace of division of the nation by the United States, Kim Kyu Sik, Kim Ku and other nationalists in south Korea supported the policy of establishing a unified government of north and south Korea in order to prevent national division, and resolutely and finally parted from extreme rightist Syngman Rhee and the reactionaries of the “Korean Democratic Party” who advocated a separate election. Kim Ku opposed election under UN observation, claiming that “the United Nations is an extraneous body with no right to interfere in the internal affairs of Korea”. Kim Kyu Sik also opposed it for the reason that a separate election would mean “the permanent division of the country”. According to author Ryo Sung Chol, seven public figures, including Kim Ku and Kim Kyu Sik, who led 12 political parties and social organizations including the Korean Independence Party, complied with the proposal for a north-south political conference as opposed to a separate election.[29]

In April 1948 there was held in Pyongyang a joint conference of 16 political parties and 40 social organizations of north and south Korea for the first time since liberation, with the participation of 695 representatives of the north and 216 the south, including Kim Kyu Sik, Hong Myong Hui and Kim Ku, who had crossed the 38th parallel to be present. The joint conference adopted a decision calling for opposition to the separate election, the withdrawal of foreign troops and the founding of a unified democratic state, and issued a manifesto. They officially called for the simultaneous withdrawal of the troops of the USSR and the United States, pointing out that "We, the Korean people, are mature enough to settle our problems by ourselves without foreign interference, and our country has many cadres prepared to settle them" as well as laid out a plan of action for peaceful reunification of Korea and the formation of a unified, democratic government. The manifesto was signed by 42 political parties and social organizations of north and south Korea which opposed the division of the country and people.[29]

Meanwhile, in south Korea, general strikes and popular uprisings, such as the Jeju uprising, arose in opposition to the US-led separate elections. The south Korean government's militant suppression of the Jeju uprising in turn sparked the Yeosu-Suncheon rebellion in South Jeolla province, which occurred from October to November in 1948, when members of a south Korean military regiment in Yeosu refused to transfer to Jeju Island to suppress the Jeju islanders. The guerrilla-style rebellion was led by 2,000 left-leaning soldiers who opposed the U.S.-backed dictator Syngman Rhee and the regime's crackdown on Jeju. In the wake of such resistance, the Rhee regime instituted the anti-communist National Security Law (Korean: 국가보안법) on December 1, 1948. This law has since been the south Korean regime's legal tool to restrict freedom of expression and to enforce anti-communist policies in the country. Under this ambiguously formulated law, thousands of opposition politicians, dissidents, journalists, students and artists have been arrested, imprisoned, tortured and executed.[44][45]

According to Ryo, at the UN, the Australian delegate demanded that the separate election be suspended because it was clear that all the political parties in south Korea except the ultra-right party would boycott it. The Canadian delegate warned that it had been an illegal and indiscreet act for the US-led "Little Assembly" on Korea to have accepted the US draft resolution, and that it would create a new and grave situation. Regardless of these statements at the UN and the clear and widespread opposition by the Korean people themselves, on May 10, 1948 the United States carried out the separate election.[29]

After the US-occupied southern regime under extreme rightist Syngman Rhee was declared in August 1948, the socialist DPRK, led by Kim Il-sung, was declared in the north in September, 1948.

Syngman Rhee and his regime are widely recognized to be responsible for the killing of 30,000 Jeju islanders from 1948-49, resulting in the death of about 10% of the island's total population. The massacre was a result of severe crack-down against Jeju islanders who protested against the division of the country and police oppression by Syngman Rhee’s administration and the US military who held an operational control over the South Korean military and police.[46]

Fatherland Liberation War[edit | edit source]

See main article: Korean War

The period that is referred to by bourgeois historians as the Korean War is considered to have occurred between 1950 and 1953. However, the 1950 start date of the war conforms to the imperialist narrative that the war began with an unprovoked attack from the North that took the US and Southern forces by surprise. However, considering the tens of thousands of people being killed in Korea throughout the 1940s by US, UN, and Southern forces, the continuous resistance in the South to the division of the country, and the numerous skirmishes that regularly occurred along the border between North and South, some consider it more accurate to frame the 1950-1953 period as an escalation of a war that was already in progress, rather than the sudden outbreak narrative favored by the bourgeois states.

Author William Blum writes of this period of escalation:

The two sides had been clashing across the Parallel for several years. What happened on that fateful day in June could thus be regarded as no more than the escalation of an ongoing civil war. The North Korean Government has claimed that in 1949 alone, the South Korean army or police perpetrated 2,617 armed incursions into the North to carry out murder, kidnapping, pillage and arson for the purpose of causing social disorder and unrest, as well as to increase the combat capabilities of the invaders. At times, stated the Pyongyang government, thousands of soldiers were involved in a single battle with many casualties resulting. [...] Seen in this context, the question of who fired the first shot on 25 June 1950 takes on a much reduced air of significance. As it is, the North Korean version of events is that their invasion was provoked by two days of bombardment by the South Koreans, on the 23rd and 24th, followed by a surprise South Korean attack across the border on the 25th against the western town of Haeju and other places. Announcement of the Southern attack was broadcast over the North's radio later in the morning of the 25th.[47]

According to Blum, citing Joseph C. Goulden's Korea: The Untold Story of the War, "On 26 June, the United States presented a resolution before the UN Security Council condemning North Korea for its 'unprovoked aggression'. The resolution was approved, although there were arguments that 'this was a fight between Koreans' and should be treated as a civil war, and a suggestion from the Egyptian delegate that the word 'unprovoked' should be dropped in view of the longstanding hostilities between the two Koreas."[47]

During the Korean War period, between 1950 and 1953, Syngman Rhee's government indiscriminately and arbitrarily killed civilians without any legal evidence, on the pretense that they may have cooperated with the North Korean People's Army. During this process, around 1 million people were massacred, including people who were against the Rhee administration. According to a letter signed by 252 Korean NGOs, including The Association for Bereaved Families of the Jeju 4.3 Victims and the Bereaved Family Association of Korean War, Rhee engaged in "the mass killing of civilians, fraudulent elections, illegal amendment of the Constitution and several cases of enforced disappearance and torture leading to the death of his opponents", crimes and corruption which he was not held legally responsible for in his lifetime, but which were later investigated and confirmed by South Korean national investigation committees.[46]

The atrocities committed by the US-backed Southern forces during this period were continuously covered up and dismissed as communist propaganda throughout the war. Western journalists, many of them leftists, who attempted to expose the atrocities committed by the US-backed regime had their passports revoked, some of them for decades, effectively exiling them from their native countries for their truthful reporting. An article that details the fates of some of these persecuted journalists notes that "The atrocities committed by the US-led UN forces are beyond dispute [...] Almost as shameful as the atrocities in Korea were the extreme steps taken to silence and eventually to punish those who sought to expose them."[48] Mass killings committed by Southern forces in Daejeon, now known as the Daejeon massacre, were falsely attributed to the Northern army in US Army reports. An article in the Asia-Pacific Journal says of this false reporting, "Such myths survived a half-century, in part because those who knew the truth were cowed into silence."[49] Silencing tactics persisted for decades under the succession of right-wing authoritarian regimes in South Korea, where people who tried to speak out or bring light to atrocities committed by the South were harassed by police, or found themselves arrested and beaten.[49][50] One author who wrote about the Jeju massacre 30 years after it had occurred was arrested by the Korean intelligence agency and tortured for three days and told not to write about the massacre again. He was then released with no charges, so a trial could be avoided so as not to further expose the public to the truth of the massacre.[51] Given the facts of such widespread and systematic suppression of the truth by the US-backed Southern regime and the US itself, who regularly dismissed reporting of their own crimes as "communist propaganda", many of which later proved to be indisputably truthful accounts of US and Southern regime crimes, caution must be taken in interpreting anti-communist narratives of the Korean War.

During the Korean War, U.S. troops killed large numbers of Korean civilians and engaged in copious firebombing with napalm, and, as was eventually revealed through declassified documents, had at certain times a policy of deliberately firing on South Korean refugee groups approaching its lines.[52] During the war, the United States dropped "635,000 tons of bombs in Korea (not counting 32,557 tons of napalm), compared to 503,000 tons in the entire Pacific Theater in World War II" and "at least 50 percent of eighteen out of the North's twenty-two major cities were obliterated."[53]

In the words of the United States Air Force General Curtis LeMay, commander of the U.S.'s Strategic Air Command, "[W]e went over there and fought the war and eventually burned down every town in North Korea anyway, some way or another, and some in South Korea, too. We even burned down Pusan—an accident, but we burned it down anyway. The Marines started a battle down there with no enemy in sight. Over a period of three years or so, we killed off—what—twenty percent of the population of Korea as direct casualties of war, or from starvation and exposure?"[54]

U.S. Naval Captain Walter Karig, in his book Battle Report: The War in Korea, a compilation from official sources, wrote: "[W]e killed civilians, friendly civilians, and bombed their homes; fired whole villages with the occupants--women and children and ten times as many hidden Communist soldiers--under showers of napalm, and the pilots came back to their ships stinking of vomit twisted from their vitals by the shock of what they had to do."[55]

US sanctions on DPRK began in conjunction with the 1950 escalation of the war, with the US imposing an export ban on DPRK and forbidding financial transactions by or on behalf of DPRK. This began with U.S. President Harry S. Truman ordering naval blockade of Korean coast and imposing a total trade embargo against north Korea in June of 1950. This was followed by the Trading with the Enemy Act in December 1950, to terminate all US economic contacts with north Korea and freezing north Korea's assets.[56]

After three years, an armistice agreement was signed that stopped the active fighting. The armistice was signed on 27 July 1953. The signed armistice established the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), the de facto new border between the two nations, put into force a cease-fire, and finalized repatriation of prisoners of war. The DMZ runs close to the 38th parallel and has continued to separate north and south Korea since the Korean Armistice Agreement was signed in 1953.

Post-war[edit | edit source]

After the armistice agreement, the US continued to prohibit all US economic contacts with DPRK in line with its general strategic controls against socialist countries.[56]

At a meeting in 1957, the U.S. informed the north Korean representatives that the United Nations Command no longer considered itself bound by paragraph 13d of the armistice, and in 1958 the U.S. abrogated paragraph 13d of the armistice by introducing nuclear weapons into south Korea.[57][58] The armistice has never been replaced with a peace treaty and the two sides remain technically at war, with the U.S. occupying the south and retaining operational control over the south Korean military in wartime, and regularly engaging in provocative joint military exercises with south Korea aimed at "decapitating" DPRK's government,[59] while enforcing strict economic sanctions against DPRK as a form of siege warfare.

The years following the Korean war, DPRK carried out its Chollima policy. The Chollima policy encouraged people to produce and innovate more in order to speed up the reconstruction of the country. In line with this policy, the DPRK concentrated its economy on heavy industry in the years following the war and it economically outperformed its southern counterpart until the early 1970s.[60]

1960s[edit | edit source]

In 1960, south Korea's right-wing dictator Syngman Rhee resigned and fled the country due to mass protests across the nation after the body of a student killed by police was found floating in the harbor. As a result of the protests against him, he fled to Honolulu, Hawaii, where he remained in exile until his death.

After Rhee's resignation, president Yun Bo-seon briefly governed in a somewhat more democratic but still bourgeois government. After thirteen months this administration was overthrown by the south Korean Army in the May 16 coup led by Park Chung-hee, former Japanese collaborator and the father of future president Park Geun-hye (who served as the 11th president of South Korea from 2013 to 2017, until she was impeached and convicted on related corruption charges).

Park Chung-hee ruled as a military dictator for 18 years and sent 320,000 troops to support the South Vietnamese puppet state in the Vietnam War.

The Korean DMZ conflict was a series of low-level armed clashes between north Korean forces and the forces of south Korea and the United States, largely occurring between 1966 and 1969 at the Korean DMZ.

The 2003 documentary Repatriation tells the story of and interviews several north and south Korean supporters of DPRK who had been arrested as spies, most of them during the 1960s, and who were subsequently imprisoned and tortured in the south for decades for refusing to give up their loyalty to DPRK. The documentary follows their struggle to be repatriated to DPRK after their release from prison in the 1990s.

1970s[edit | edit source]

In 1972, the Supreme People's Assembly elected Kim Il-sung as President of the DPRK.

In south Korea, the fourth republic was founded on the approval of the Yushin Constitution in the 1972 constitutional referendum, codifying the de facto dictatorial powers held by President Park Chung-hee.

An Amnesty International mission from 1975, conducted when Park Chung-hee was in power, found that torture was "frequently" used by south Korea's law enforcement agencies, "both in an attempt to extract false confessions, and as a means of intimidation." Systematic harassment of citizens by law enforcement agencies was also found to be "commonplace" by the investigation. The report states that detention without charge of journalists, lawyers, churchmen and academics was frequent. The mission also found that lawyers would be detained on house arrest and prevented from coming to trials to present defenses for their clients, and bodies of likely torture victims burned before they could be examined.[61]

The Fourth Republic entered a period of political instability under Park's successor, Choi Kyu-hah, and the escalating martial law declared after Park's death.

Choi was unofficially overthrown by Chun Doo-hwan in a coup d'état of December Twelfth in December 1979, and began the armed suppression of the Gwangju Democratization Movement against martial law.

1980s[edit | edit source]

During Chun Doo-hawn's presidency in south Korea, he perpetrated the largest massacre of Korean civilians since the Korean war. In May 1980, protests against martial law began in Gwangju, which were met with special warfare troops. Estimates vary as to the amount of casualties, but they range from 165 at the most conservative, to over 300. Some also claim that up to 2,300 civilians were killed in the Gwangju massacre, in response to the May 18 uprising also known as the Gwangju uprising.[62] Chun Doo-hawn's administration faced growing opposition from the democratization movement of the Gwangju Uprising, and the June Democracy Movement of 1987 resulted in the election of Roh Tae-woo in the December 1987 presidential election. Roh's election was the first direct presidential election in 16 years. The fifth republic was dissolved three days after the election upon the adoption of a new constitution that laid the foundations for the relatively stable (although bourgeois and rife with corruption scandals) democratic system of the current sixth Republic of Korea.

In 1988, south Korea and the US eased isolation of north Korea by opening bilateral dialogue and allowing limited export of goods to the North for humanitarian purposes. Some travel restrictions were also lifted on a case-by-case basis. However, in that same year, DPRK was added to the U.S. State Department "State Sponsors of Terrorism" list.[63]

On March 25, 1989, south Korean pastor and activist Moon Ik-hwan, representing the National Federation of Democratic Movements (Korean: 전국민족민주운동연합; Hanja: 全國民族民主運動聯合; abbreviated 전민련), travelled to DPRK and met with Kim Il-sung to discuss Korean reunification. He and some other individuals had travelled there after Kim Il-sung had invited the leaders of all south Korean political parties as well as some religious figures to attend an inter-Korean dialogue. On April 2, pastor Moon and his party held two talks with President Kim Il-Sung and issued a joint statement with the Committee for the Peaceful Reunification of the Fatherland. Pastor Moon and his party returned home to south Korea on April 13 after completing their 10-day visit to DPRK. As soon as they returned to south Korea, the government executed a prior arrest warrant and arrested and imprisoned them on charges under the National Security Act, such as receiving orders, infiltrating and escaping, meeting and communication, and encouraging praise of an anti-state group.[64][65]

In 1989, Pyongyang held the World Festival of Youth and Students. A south Korean activist named Lim Su-kyung (Korean: 임수경; also romanized as Lim Soo-kyung or Rim Su Gyong) took part in the festival, although this was illegal for her to do under south Korean law. She attended the festival representing the student organization Jeondaehyop (전대협, an abbreviation of 전국대학생대표자협의회), now known as Hanchongryun (한총련, abbreviation of 한국대학총학생회연합). In the north, she was celebrated for her decision to take part in the festival, and dubbed the "Flower of Reunification" (Korean: 통일의 꽃) in the north's media. Upon her return to the south, she was arrested and ended up in a Seoul prison, sentenced to 5 years. Later in life, she became a politician in the south.[66]

1990s[edit | edit source]

A unified team under the name Korea (KOR) competed in 1991 World Table Tennis Championships and FIFA World Youth Championship with athletes from both north and south Korea.[67] In 1991, the team used the Unification Flag and the anthem "Arirang".

Kim Jong-il became Supreme Commander of the Korean People's Army in 1991.

In 1990, south Korean pastor Moon Ik-hwan had been released from prison in consideration of his poor health and old age. After his release, he resumed his pro-unification and democratization activism despite receiving warnings that he may be re-imprisoned by the south Korean authorities for such activities. A 1991 Amnesty International report on his activities stated that since his release, he was reported to have delivered speeches at at least 100 meetings of students and dissidents and to have participated in other political activities. In December 1990, police warned him to stop speaking to gatherings of students and dissidents about his visit to DPRK and about DPRK's ideology. In January of 1991 he was placed under house arrest to prevent him from attending the inauguration meeting for the preparatory committee of the south Korean headquarters of Pomminnyon (Pan-National Alliance for Reunification of Korea). He later became chairperson of the preparatory committee. On June 6 of 1991, Reverend Moon Ik-hwan was rearrested on the grounds that he had violated the terms of his parole by engaging in political activities and that his health had improved.[68]

In 1992, the Pyongyang Declaration, titled "Let Us Defend and Advance the Cause of Socialism" was published on April 20. The declaration was a joint-communique in which various communist bloc and fraternal parties which remained after the fall of the Soviet Union declared their intention to continue to defend and advance the socialist cause. At the time of its original signing, 70 political parties signed the declaration, with its number of signatories increasing over time into the hundreds, reaching 300 as of 2017.[69] The document declares its signatories' firm conviction to defend and advance the socialist cause and explains that the path of socialism is an untrodden one and, therefore, the advance of socialism is inevitably accompanied by trials and difficulties. It asserts that although facing setbacks and attacks from the collusion of imperialists and reactionaries, socialism represents the future of mankind and that all parties striving for socialism should firmly maintain independence and firmly build up their own forces and that each party should work out lines and policies which "tally with the actual situation of the country where it is active and with the demands of its people and implement them by relying on the popular masses". It says that socialist cause is a national one and, at the same time, a common cause of mankind, and that "socialism is carved out and built with a country or national state as a unit." It states that all parties should cement the ties of comradely unity, cooperation and solidarity on the principles of independence and equality and defend the cause of socialism, not give up their revolutionary principles under any circumstances, and concludes with the statement that the socialist cause shall not perish.[70]

In July 1994, Kim Il-sung passed away.

Kim Jong-il became the General Secretary of the party on October 8, 1997.[71]

The period of economic crisis, floods, and famine in DPRK known as the Arduous March lasted from 1994 to 1998. The thriving north Korean economy, which had exceeded south Korea's in production of electricity, coal, fertilizer, machine tools and steel even into the 1980s, was brought to a halt in the 1990s with the overthrow of the Soviet Union and a string of natural disasters. Factors such as the fall of the Soviet Union and worldwide economic shifts in its wake, unprecedented natural disasters, DPRK only having 15% arable land,[42] and economic sanctions imposed on DPRK compounded at this time, contributing to the severity of the crisis.[72]

Beginning in 1997, the period known as the Asian financial crisis or the IMF crisis affected several Asian countries, with south Korea being among some of the most heavily impacted, with the crisis resulting in the bankruptcy of major south Korean companies and the imposition of austerity measures. The generation of people who entered the job market in this period are sometimes called the "IMF generation" and have faced a pattern of worsened economic conditions and struggling with job security.[73][74]

In south Korea in the late 1990s, amnesty was declared for certain elderly and ill political prisoners who had been held in prison for decades, facing torture and solitary confinement for refusing to renounce communism and their support for DPRK. Some of these prisoners then began a movement to be repatriated to DPRK, with some of them being allowed to return while others remained in south Korea, some willingly and some unwillingly, with many of the participants mistakenly believing that more repatriations and further freedom of movement between north and south would follow.[75] This series of events is detailed in the 2003 documentary Repatriation, which follows the release of several of these political prisoners and the different events in their lives afterward.

DPRK's hopes for direct talks with the United States, a formal peace treaty ending the Korean War and normalized relations with the U.S. seemed potentially realizable in the last years of the Clinton administration (which lasted from 1993 to 2001). The United States and DPRK signed the General Framework Agreement, which provided that DPRK would seal its heavy water nuclear energy reactors in return for normalized diplomatic relations with the U.S. government and assistance constructing light water nuclear reactor facilities. Pursuant to the agreement, DPRK stopped its nuclear program at this time.[42]

2000s[edit | edit source]

The south Korean policy towards DPRK from the late 1990s to mid 2000s is known as the period of "Sunshine Policy" and is primarily associated with the south Korean Kim Dae-jung administration (1998–2003) and the Roh Moo-hyun administration (2003–2008).

During this time, a notable attitude of reconciliation between north and south Korea was expressed by south Korean leadership toward DPRK, and on June 13-15, 2000 the leaders of south and north Korea met for the first time since the war. South Korean president Kim Dae-jung and DPRK leader Kim Jong-il signed an agreement calling for family reunions, economic cooperation, social and cultural exchanges and follow-up governmental contacts between the north and south to ease tensions. This is known as the June 15th North–South Joint Declaration or the 6.15 Inter-Korean Joint Declaration.

In 2002, President Bush's State of the Union address singled out Iran, Iraq and DPRK as the so-called "axis of evil" for their supposed pursuit of weapons of mass destruction. The next year, the U.S. military invaded Iraq. It was in this context that the DPRK, under the leadership of Kim Jong Il, tested highly publicized nuclear weapons. Liberation News notes that "This was not an act of international terrorism, but a maneuver to bring the United States back to the negotiation table, which worked."[42]

Since the beginning of the DPRK nuclear tests in 2003, the Bush and Obama administrations respectively lifted some sanctions to facilitate negotiations around DPRK denuclearization. However, they then reinstated them when the negotiations failed to produce the results desired by the US.[56][63] Following the country’s 2006 nuclear test, the US, EU, and others added more stringent sanctions, which have periodically intensified since then. Sanctions now target oil imports, and cover most finance and trade, and the country’s key minerals sector.[76]

2010s[edit | edit source]

Kim Jong-il passed away on December 17, 2011.[71] Following this, Kim Jong-un was named supreme commander of the military.[77]

A period of mourning ensued in DPRK following Kim Jong-il's death. Chinese President Hu Jintao also reached out in solidarity to DPRK after the announcement of Kim Jong Il's death, and Cuba declared a period of mourning from Dec. 20-22, during which flags would be flown at half-mast. A Liberation News article from the time notes that the Western imperialist media took the opportunity at this time to make insinuations and accusations to portray north Koreans as "brainwashed" via the West's media commentary about the traditional mourning rituals Koreans publicly engaged in at the time. Liberation News points out that this portrayal is part of the West's continued campaign to manufacture consent for the overthrow of DPRK's leadership, using disingenuous concern over the so-called "cult of personality" as a pretext.[42]

In 2012, a left-wing south Korean activist named Roh Su-hui (Korean: 노수희; also spelled Ro Su Hui and Noh Su-hui), member of the Pan-National Alliance for Korea's Reunification (Korean: 조국통일범민족연합; abbreviated 범민련; "Pomminryon"), was arrested at Panmunjom after having entered into DPRK months before without approval from the southern regime. He had travelled to DPRK in order to attend a memorial service marking the 100th day since the death of Kim Jong-Il. At Panmunjom, he was waved farewell by a crowd of people from the northern side, who waved Korean unification flags and flowers. Officials of the DPRK accompanied him to Panmunjom to see him off. Before stepping over the border, Roh shouted "Long live national reunification, by our nation itself!" (Korean: "우리민족끼리 조국통일 만세!") holding up a unification flag and flowers. After crossing the border, south Korean authorities seized him, and a struggle ensued where he was tackled to the ground, then lifted and carried away by the southern authorities, who bound his arms and hands with rope as they brought him into custody. He was sentenced to four years in prison and to have his suffrage stripped for three years after release. Another activist, Won Jin Wook, received a three-year prison sentence for communicating with DPRK officials to arrange the trip.[78][79][80]

Park Geun-hye, daughter of dictator Park Chung-hee, was in office as the 11th president of south Korea from 2013–2017 until she was impeached and convicted on corruption charges following public demonstrations, commonly known as the Candlelight Revolution or Candlelight Demonstrations. She became the first south Korean president to be removed from power by impeachment, and was sentenced to 24 years in prison, but received a pardon and was released in 2021 after serving just under 5 years.[81] Park Geun-hye's presidency was followed by Moon Jae-in (in office 2017–2022).

According to a 2017 article by CNN, 49 countries, including Cuba, Iran, and Syria have violated sanctions and have traded with DPRK.[82] In 2017, sanctions imposed by the UN caused thousands of DPRK workers who had been working abroad to be forced to return to DPRK as well as led to the closure of numerous DPRK companies and joint ventures.[83] According to Nodutdol, in 2018, 3,968 people in the DPRK, who were mostly children under the age of 5, died as a result of shortages and delays to UN aid programs caused by sanctions.[63]

Talks between General secretary Kim Jong-un and Former U.S. President Donald Trump began on June of 2019 to discuss disarmament and potential reunification with the Republic of Korea.

2020s[edit | edit source]

In January 2020 when south Korean President Moon Jae-In expressed interest in developing tourism to north Korea, the US ambassador Harry Harris blocked this effort, claiming that "independent" tourism plans would have to undergo U.S. consultation. The U.S. ambassador emphasized that the items inside South Korean tourists' luggage could violate sanctions.[63]

The 13th and current president of south Korea is Yoon Suk-yeol of the conservative People Power Party, who took office in 2022. His presidency has been surrounded with criticism, with numerous protests drawing thousands of participants calling for his resignation and his approval rating frequently falling below 30%.[84] On August 13, 2022, thousands of south Korean unionists and their progressive supporters rallied in downtown Seoul to protest against joint US-south Korea war game exercises. In a video uploaded by Press TV, Oh Eun-Jung of the National Teachers Union was quoted as saying "The threat of nuclear war is growing on the Korean peninsula, conservative forces of Yoon Suk-yeol in south Korea and those in the U.S. are frantically conducting aggressive war drills in the sky, the land, and the sea, and are about to start large-scale military exercises, aimed at the invasion of north Korea. We must stamp out this behavior of anti-reunification forces." In the same video, construction worker Lee Seung-Woo stated, "We not only oppose the war exercises, but we want the U.S. Forces Korea, which is actually controlling and interfering with the Korean peninsula to leave this land. We believe that only then will the eighty million Koreans from both north and south be able to live peacefully."[85]

In September 2022, a statement on the nuclear force policy of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea was carried by DPRK's Korean Central News Agency (KCNA), noting that while the government considers nuclear weapons a last resort, it would deploy them to prevent aggression that seriously threatens the security of the state and people. The statement stressed that DPRK "does not threaten or use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear countries," and warned it would forcefully respond to aggression, or to nations threatening the DPRK by "colluding with other nuclear-armed states."[86]

Culture[edit | edit source]

The folk song "Arirang" (Korean: 아리랑) is regarded as a representative folk song of Korea, sung throughout the nation and presenting many different orally transmitted versions. Arirang typically contains a gentle and lyrical melody. Arirang songs speak about leaving and reunion, sorrow, joy and happiness. The various categories differ according to the lyrics and melody used. While dealing with diverse universal themes, the simple musical and literary composition invites improvisation, imitation and singing in unison, encouraging its acceptance by different musical genres. Both DPRK and south Korea have submitted the song to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list. DPRK's submission states that Arirang folk songs reinforce social relations, thus contributing to mutual respect and peaceful social development, and help people to express their feelings and overcome grief. They function as an important symbol of unity and occupy a place of pride in the performing arts, cinema, literature and other works of contemporary art. South Korea's submission notes that Arirang is a popular subject and motif in diverse arts and media, including cinema, musicals, drama, dance and literature, describing it as an evocative hymn with the power to enhance communication and unity among the Korean people, whether at home or abroad.[87][88]

Languages[edit | edit source]

Korean language[edit | edit source]

Korean is the official language of both north and south Korea.

There are regional dialects and accents of Korean spoken throughout the Korean Peninsula. In general they are largely mutually intelligible with standardized forms of Korean. Additionally, despite the division of the country into north and south, the language has not diverged to the point of unintelligibility, although certain vocabulary, spelling, and pronunciation differences do exist. Notably, in the north, a preference for using native Korean words is shown, while in the south, foreign loanwords show a higher prevalence of use.

Korean is also the official language of Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in Jilin Province, China (along with Mandarin). Other large groups of Korean speakers are found in China, the United States, Japan, former Soviet Union and elsewhere.

Jeju language[edit | edit source]

The Jeju language, which is closely related to Korean, is an endangered language whose main community of speakers come from Jeju Island. While often classified as a divergent dialect of the Korean language, the variety is referred to as a language in local government and increasingly in both South Korean and foreign academia. Jeju language is not mutually intelligible with the mainland dialects of South Korea. Most people in Jeju Island now speak a variety of Korean with a Jeju substratum, and efforts to revitalize the endangered language are ongoing.

North and South Korean Sign Language[edit | edit source]

A form of Korean Sign Language (KSL) is used in both north and south Korea. Following the division of the country, the heterogeneity of sign language has accelerated. Researchers Lee and Choi compared the handshapes of north and south Korean Sign Languages, and found in 2017 that there was 15% both hands agreement, 21% dominant hand agreement, 23% nondominant hand agreement, and 71% disagreement.[89] A YouTube channel called Sonmal Sueo (Korean: 손말수어) is dedicated to presenting the differences between north and south Korean signs to promote communication and understanding.[90]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Ri Yong Ho, DPRK Minister for Foreign Affairs. "Statement by H.E. Mr. RI YONG HO, Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea at the General Debate of the 72 Session of the United Nations General Assembly." New York, 23rd September 2017. gadebate.un.org. Archived 2022-08-28.

- ↑ People's Democracy Party and Liberation School. “70 Years Too Long: The Struggle to End the Korean War – Liberation School.” Liberation School – Revolutionary Marxism for a New Generation of Fighters, 25 June 2020. Archived.

- ↑ “How to Speak the North Korean Language: Part 1” Tongil Tours. March 10, 2017. Archived 2022-10-25.

- ↑ 이진욱. “언론은 왜 북한을 '북측’이라고 할까?” 노컷뉴스. 노컷뉴스. January 22, 2018. Archived 2022-10-25.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 “[1조] 북한의 국호에 민주주의를 유지하는 이유는?” 주권방송. The615tv. July 29, 2022. Archived 2022-09-04.

- ↑ “How to Speak the North Korean Language: Part 2” Tongil Tours. March 19, 2017. Archived 2022-10-25.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 "The National Atlas of Korea: Territorial History of Korea." Comprehensive Edition, 2022. Archived 2024-03-15.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 “The Beginnings of Korea’s History (Prehistoric Times – Gojoseon) : Korea.net : The Official Website of the Republic of Korea.” Korea.net. 2021. Archived 2022-10-12.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 "The Outline of Korean History." Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1977. Pyongyang, Korea.

- ↑ Faraz German (2020-10-05). "Korean mythology – Dangun and the origin of the ancient Korea" Embassy of the Republic of Korea to Norway. Archived from the original on 2023-12-08. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Violet Kim. "Dangun, Father of Korea: Korea’s Foundation Tale Lends Itself to Many Interpretations." Korea.net. Archived 2023-08-25.

- ↑ Shaffer, David. “The Heavens Open: Korea Is Created.” Gwangju News. October 7, 2021. Archived 2023-08-25.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Three Kingdoms and Other States." Korea.net.

- ↑ Cartwright, Mark. "Gaya." World History Encyclopedia, 2016-09-28.

- ↑ Lee Seung-ah. "Learn the island's history at the Jeju National Museum." Korea.net, 2014-12-02.

- ↑ Rodong Sinmun. Archived from the original on 2023-08-19.

- ↑ "Phalmandaejanggyong" (2023-05-28). Rodong Sinmun. Archived from the original on 2023-08-19.

- ↑ “Medieval and Early Modern History.” National Museum of Korea. Archived 2023-08-26.

- ↑ "Korean Characters Hunminjongum, Treasure and Pride of Nation" (2023-04-27). Rodong Sinmun. Archived from the original on 2023-08-19.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Joseon Dynasty." Korea.net. Archived 2023-01-10.

- ↑ “북한 한글날은 '조선글날’인 1월15일…왜?” ("Why is north Korea's Hangeul day, 'Chosongul day', on January 15?") 중앙일보. 중앙일보. The JoongAng. October 9, 2014. Archived 2023-08-26.

- ↑ "A Historic Relic, Monument to Great Victory in Pukgwan" (2023-02-19). Rodong Sinmun. Archived from the original on 2023-08-19.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 "The Fall of Joseon: Imperial Japan’s Annexation of Korea." Korea.net. Archived 2022-09-12.