More languages

More actions

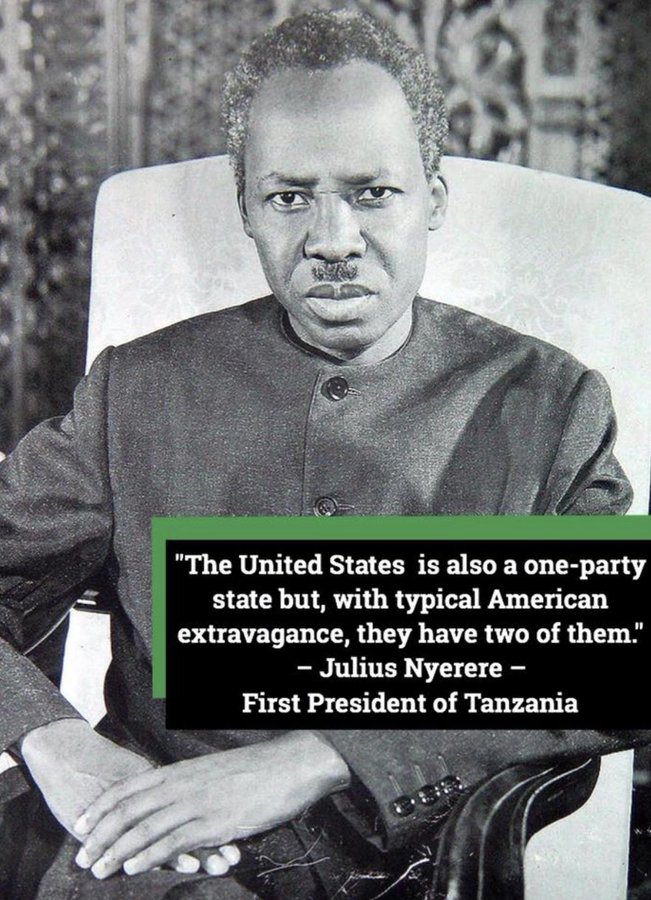

Julius Nyerere | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 13 April 1922 Butiama, Tanganyika Territory |

| Died | 14 October 1999 London, England, UK |

| Political orientation | African socialism Ujamaa |

| Political party | TANU |

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian politician who served as Prime Minister of Tanganyika from 1961 until 1964. In 1964, Tanganyika and Zanzibar united to form the United Republic of Tanzania, and Nyerere became Tanzania's first president from 1964 to 1985. Nyerere is often referred to as Mwalimu, meaning "teacher" in Swahili.[1]

Nyerere promoted socialist policies, especially promoting the concept of ujamaa, and was a prominent figure in the Non-Aligned Movement.[2] He was also a supporter of policies promoting African unity and during his administration a number of organizations and individuals associated with African liberation movements were hosted in Tanzania.[3][4] In 1985, Nyerere stepped down from the presidency but remained the chair of the Party Chama cha Mapinduzi (CCM) until 1990.[5] In 1987 he was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize.[4] Nyerere passed away from leukemia in 1999.[6]

Life[edit | edit source]

Early life and education[edit | edit source]

Nyerere was born on April 13, 1922 in Butiama village. His father was Chief Nyerere Burito of the Zanaki ethnic group and his mother Christina was the fifth of the chief's 22 wives. Nyerere studied at Mwisinge Primary School, a 26 mile daily walk from home to school. He also studied at the Catholic Mission Secondary School of St Mary's, Tabora. He attained a diploma in education in 1946 from Makerere University College in Uganda, then returned to teach in Tabora. In 1949 he became the first Tanganyikan student to be sent to Edinburgh University, graduating in 1952 with an MA in history and economics.[6]

British author and Labour Party politician John Charles Hatch, who first met Nyerere while he was a student in Scotland in 1950 described Nyerere as "contemplative" and "introverted" and "never strident or dogmatic". Hatch, who met Nyerere several more times over the years, wrote that in his observation, Nyerere "has never deviated from the personality I first knew as a student; his single-minded but humble concern has been for the welfare of his fellow countrymen and for their place in the world."[7]

After returning to Tanganyika, Nyerere was appointed to teach at St. Francis Secondary School, Pugu. During this time he joined the Tanganyika African Association (TAA), an unofficial political organization which would eventually become the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU).[6]

Independence movement[edit | edit source]

Following the Second World War, Tanganyika had been designated as a UN trust territory, with Britain mandated for its development.[8] The UN's trusteeship council was supposed to promote development toward self-government and independence in trust territories, periodically evaluating their conditions. In this context, TANU, headed by Nyerere, pushed for independence via legal and electoral means, gaining widespread support when general elections were held in 1960.[8]

Historian and activist Walter Rodney wrote about the conditions in this period of African independence movements. Rodney evaluated that these movements were "essentially political fronts or class alliance [...] while the workers and peasants formed the over-whelming numerical majority, the leadership was almost exclusively petty bourgeois". As Rodney explains, "Imperialism defined the context in which constitutional power was to be handed over, so as to guard against the transfer of economic power or genuine political power. The African petty bourgeoisie accepted this, with only a small amount of dissent and disquiet being manifested by the progressive elements such as Nkrumah, Nyerere and Sekou Toure."[9] While Rodney regarded such leaders as playing a historically progressive role and counted Nyerere among the more advanced nationalists, ultimately, he wrote that "the petty bourgeoisie were reformers and not revolutionaries. Their class limitations were stamped upon the character of the independence which they negotiated with the colonial masters."[9]

Summarizing his own political education and the development of his ideas and understanding of socialism at the time of the independence movement, Nyerere commented in a 1984 interview that "My political education was of the western liberal type up to the time of independence" and that "As for socialism, my first contact was with European, mainly British, socialism, not with the socialism of Marx and Lenin. When I started the movement towards independence, we talked of independence, not socialism, about which we had some vague ideas."[10] He stated that this was "not altogether a bad thing" in his view because "it allowed us to form our own ideas after independence and in the face of the real problems that came to us, rather than through a particular theory."[10]

Presidency[edit | edit source]

Nyerere became prime minster when Tanzania's mainland (then called Tanganyika), formally gained independence from British rule on December 9, 1961. When a new constitution was implemented in 1962, Nyerere became president. On April 26, 1964, the Republic of Tanganyika and the People's Republic of Zanzibar united to form the United Republic of Tanzania, of which Nyerere was president.[8]

Nyerere announced the Arusha Declaration in 1967, expressing TANU's policy of building a socialist state.[11] Historian Vijay Prashad notes that this announcement "discomforted" the British imperialists and Tanzanian bourgeoisie, the "owners and managers of most of the country's resources" including mines and the land, and that, "Hemmed in by pressures from the advanced industrial states, the aristocratic rural classes, and the emergent mercantile classes, the new state had little time" to pursue the necessary institutional changes envisioned in TANU's policies for socialist construction. Under Nyerere's administration, collectivization programs were organized that sent peasants to ujamaa villages, sometimes relying on coercion by the military.[11]

Nyerere remained chairman of TANU until 1977, when the party (still under his leadership) became Chama cha Mapinduzi (CCM).[6]

Later life[edit | edit source]

After stepping down from the presidency, Nyerere remained chairman of CCM from 1985 to 1990. After his retirement, he moved back to his home village of Butiama. In retirement, Nyerere continued to advocate for countries of the global south, travelling and meeting with world leaders. In 1991, he established the South Centre in Geneva, an intergovernmental organization focused on Third World development strategies. He also served as the UN’s chief facilitator for the Burundi peace negotiations between 1994 and 1999.[6] Nyerere passed away from leukemia in a London hospital on October 14, 1999[4] and was buried at Butiama.[6]

Views[edit | edit source]

National liberation[edit | edit source]

In 1969, Nyerere delivered a speech in which he expressed that national liberation struggles should be supported regardless of whether the people conducting the struggle may be (as he put it) capitalists, liberals, communists or socialists. In Nyerere's words, "Tanzania must support the struggle for liberation [...] regardless of the political philosophy of those who are conducting the struggle. If they are capitalists, we must support them, if they are liberals, we must support them, if they are communists, we must support them, if they are socialists, we must support them. We support them as nationalists. The right of a man to stand upright as a human being in his own country comes before questions of the kind of society he will create once he has that right. Freedom is the only thing that matters until it is won."[12]

Non-Alignment[edit | edit source]

In a 1967 address titled "Tanzania Policy on Foreign Affairs" at the TANU national conference, Nyerere expressed the position of non-alignment held by Tanzania, explaining that Tanzania had "no desire to be, and no intention of being, 'anti-west' in our foreign policies" desiring to live in friendship with all states and all peoples and to center Tanzania's interests rather than get caught up in other nations' rivalries and "not allow anyone to choose any of our friends or enemies for us". He noted that "Only in the case of South Africa, the racialist colonialism of Portugal, and the Smith Regime of Southern Rhodesia, does such settlement of differences seem inherently impossible" until those countries would recognize "the equality of men".[13]

International Monetary Fund[edit | edit source]

In a 1980 speech to diplomats accredited to Tanzania, Nyerere rejected the neoliberal conditionalities and structural adjustment programs typically demanded by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). He described it as "repugnant" that the IMF would exploit the country's economic problems in order to interfere with the management of Tanzania's economy, and asked "When did the IMF become an International Ministry of Finance? When did nations agree to surrender to it their power of decision making?"[14]

Explaining his position further, Nyerere stated:

Tanzania is not prepared to devalue its currency just because this is a traditional free market solution to everything and regardless of the merits of our position. It is not prepared to surrender its right to restrict imports by measures designed to ensure that we import quinine rather than cosmetics, or buses rather than cars for the élite.

My Government is not prepared to give up our national endeavour to provide primary education for every child, basic medicines and some clean water for all our people. Cuts may have to be made in our national expenditure, but we will decide whether they fall on public services or private expenditure. Nor are we prepared to deal with inflation and shortages by relying only on monetary policy regardless of its relative effect on the poorest and less poor.

Our price control machinery may not be the most effective in the world, but we will not abandon price control; we will only strive to make it more efficient. And above all, we shall continue with our endeavours to build a socialist society.[14]

Nyerere also insisted that there needs to be a change in the management structure of the IMF, "to be made really international, and really an instrument of all its members, rather than a device by which powerful economic forces in some rich countries increase their power over the poor nations of the world" and concluded "The problems of my country and other Third World countries are grave enough without the political interference of IMF officials. If they cannot help at the very least they should stop meddling."[14]

Palestine[edit | edit source]

Nyerere expressed in a 1967 speech that "The establishment of the state of Israel was an act of aggression against the Arab people." While Nyerere acknowledged that the international community had accepted the concept of Israel as a state and that Tanzania recognized Israel as a state, he emphasized that Arab states could not be "beaten" into accepting Israel as a state, and that "attempts to coerce the Arab states into recognizing Israel – whether it be by refusal to relinquish occupied territory, or by an insistence on direct negotiations between the two sides – would only make such acceptance impossible."[13]

Nyerere expressed that "Israel's desire to be acknowledged as a nation is understandable" but that "Israel's occupation of the territories of U.A.R., Jordan, and Syria, must be brought to an end. Israel must evacuate the areas she overran in June this year—without exception—before she can reasonably expect that the Arab countries will begin to acquiesce in her national presence."[13]

In a 1984 interview, Nyerere commented: "We have never hesitated in our support for the right of the people of Palestine to have their own land. Our generation was a generation of nationalists struggling for the independence of our own countries – that is what we were there for – but the plight of the Palestinians is very different and much worse. When we were fighting for our independence, I was in Tanganyika, Kenyatta was in Kenya. Even now, the Namibians and the South Africans are in their own country. But the Palestinian plight is more terrible and unjust; they have been deprived of their own country, they are a nation without a land of their own. They therefore deserve the support of Tanzania and the entire world."[10]

Works[edit | edit source]

Throughout his life and political career, Nyerere delivered many speeches and interviews in addition to producing and contributing to various written works in both English and Swahili. The 1968 book Ujamaa - Essays on Socialism (Swahili version titled Ujamaa) collects various speeches and writings by Nyerere (and TANU) spanning from 1962 to 1968.[15] Other collections include Freedom and Unity (Uhuru na Umoja), selected writings and speeches from 1952-65; Freedom and Socialism (Uhuru na Ujamaa), selected writings and speeches from 1965-67; Freedom and Development (Uhuru na Maendeleo), selected writings and speeches from 1968-73; and Man and Development (Binadamu na Maendeleo), published 1974.[16] Nyerere also published Swahili translations of Shakespeare works, Julius Caeser (Swahili: Juliasi Kaizari) and The Merchant of Venice (Swahili: Mabepari wa Venisi).[16] Prior to his passing, he was working on a Swahili translation of Plato's The Republic.[17]:41

Library works[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ CGTN Africa (2013-12-31). "Faces Of Africa - Mwalimu Julius Nyerere". YouTube.

- ↑ "The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM)". Julius Nyerere Leadership Centre. Archived from the original on 2024-03-02.

- ↑ “As stated before, there is no single African liberation movement that did not enjoy the support of Tanzania. Frelimo was founded in Tanzania; the ANC, after its banning in South Africa, opened its first external mission in Tanzania; and MOLINACO, MPLA, ZANU, ZAPU, PAC and many others had Tanzania's full support. In the UN Decolonisation Committee (known as the Committee of 24), Tanzania's then permanent representative to the UN, Salim Ahmed Salim, held the chairmanship for several years. In the Non-Aligned Movement, Tanzania was in the forefront in mobilising support to the liberation struggles. Tanzania's support to the liberation movements was not only manifested in the political and diplomatic arenas but also in the material and military fields. The Tanzanian population was mobilised many times to give material support to the liberation movements. The Tanzania People's Defence Forces trained thousands of military cadres of those liberation movements which wanted that kind of support. Tanzania was used as a facility for either storing or transporting different types of goods to the liberation movements.”

Chambi Chachage, Annar Cassam (Eds.) (2010). Africa's Liberation: 'Mwalimu Julius Nyerere: an intellectual in power (Haroub Othman)' (pp. 38-9). Pambazuka Press. - ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere - Biography." JuliusNyerere.org. Archived 2024-07-04.

- ↑ "Biography : Julius Kambarage Nyerere". Marxists.org. Archived from the original on 2024-03-24.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Chambi Chachage, Annar Cassam (Eds.) (2010). Africa's Liberation: The Legacy of Nyerere: 'A short biography of Julius Nyerere (by Madaraka Nyerere)'. Pambazuka Press.

- ↑ John Hatch (1972). Tanzania: A Profile: 'Introduction'. New York: Praeger Publishers.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "EVERY DECEMBER 9TH : IS THE COMMEMORATION OF TANZANIA MAINLAND INDEPENDENCE DAY" (2023-12-09). Embassy of the United Republic of Tanzania: Tokyo, Japan.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Walter Rodney (1974). Aspects of the International Class Struggle in Africa, the Caribbean and America. [MIA]

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Chambi Chachage, Annar Cassam (Eds.) (2010). Africa's Liberation: 'President Nyerere talks to El Mussawar (1984)'. Pambazuka Press.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Vijay Prashad (2008). The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World: 'Arusha' (pp. 191–6). [PDF] The New Press. ISBN 9781595583420 [LG]

- ↑ Chambi Chachage, Annar Cassam (Eds.) (2010). Africa's Liberation: The Legacy of Nyerere: 'Introduction (Annar Cassam)' (pp. xiii). Pambazuka Press.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Nyerere, Julius K. "Tanzania Policy on Foreign Affairs." October 16, 1967. (PDF). Archived 2023-10-01.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Sven Hamrell, Olle Nordberg (Eds.) (1980). Development Dialogue: The International Monetary System and the New International Order, vol. 1980:2: 'No to IMF Meddling: Extract from President Nyerere's New Year Message 1980 to the Diplomats accredited to Tanzania'. [PDF] Motala, Sweden: Development Dialogue.

- ↑ Nyerere, Julius K. (1968). Ujamaa - Essays on Socialism. Dar es Salaam: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Nyerere, Julius K. (1974). Man and Development | Binadamu na Maendeleo: 'Other Books by the Author'. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Chambi Chachage, Annar Cassam (Eds.) (2010). Africa's Liberation. Pambazuka Press.