More languages

More actions

| People's Republic of China 中华人民共和国 Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó | |

|---|---|

| |

| Capital | Beijing |

| Largest city | Chongqing |

| Official languages | Mandarin |

| Dominant mode of production | Socialism |

| Government | Unitary Marxist-Leninist people's republic |

• President and General Secretary | Xi Jinping |

• Vice President | Han Zheng |

• Premier | Li Qiang |

| History | |

• Unification of China by Qin Shi Huang | 221 BCE |

• Founding of the Yuan dynasty | 1271 November 5 |

• Establishment of the People's Republic of China | 1949 October 1 |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 1,463,140,000 |

| Labour | |

• Labour force | 784 million[1] |

• Labour force participation | 48.07% |

• Occupation | 53.3% services 39.4% industry 7.3% agriculture[2] |

• Unemployment rate | 5.5% |

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a socialist country in East Asia.[3] It is the world's most populous country with a population of around 1.4 billion in 2019. It is led by the Communist Party of China (CPC).

The Chinese constitution states that the PRC "is a socialist state under the people's democratic dictatorship led by the working class and based on the alliance of workers and peasants" and that the state organs "apply the principle of democratic centralism."[4] Over 95% of the Chinese population supports its government.[5]

The People's Republic of China is one of only five socialist states in the world today (alongside Cuba, Laos, People's Korea and Vietnam). Over the last few years it has emerged as the world's leading economic power, and as a result has been subjected to near-constant demonization from Western media and propaganda outlets.[6][7] The PRC's guiding ideology is Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought.[8]

History

In accordance with historical materialism, Chinese history can be divided into primitive, slave, and feudal eras. Modern Chinese historians do not, however, use the terms "capitalist era" or "socialist era." This is because the capitalist period of Chinese history fits into the broader New-Democratic Revolution period (1919–1949). The socialist era, which began in 1956, is likewise not considered an era of Chinese history but instead is considered part of the People's Republic period (starting in 1949).[9]

Early history

Antiquity

China's recorded history goes back more than 3,200 years. Before the unification of China under the Qin and Han dynasties, a class of warriors controlled the land and collected tribute. Most economic activity was self-sufficient but there was some high-value trade organized by royal courts. Literate administrative officials were awarded with land grants that became hereditary property. The monarch retained ultimate ownership of all land.[10]

Imperial China

China transitioned from slavery to feudalism under the Zhou and Qin dynasties, when government officials built up large land holdings. Under feudalism, almost all land was owned by the emperor, nobility, and landlords. Peasants had to give half or more of their crop to the landowners and landlords could abuse or kill peasants at will. Small landholders who farmed land distributed to them by the emperor also existed in this period. Exchange did not have an important role in the economy during this period.[11] The number and location of markets were restricted and they were strictly controlled by the emperor.

In imperial China, government officials were recruited based on recommendations from serving officials, allowing aristocratic families to stay in power for generations. The Han dynasty collapsed in 220 CE and China was reunified under the Sui and Tang dynasties. The An Lushan rebellion from 755 to 763 weakened the Tang dynasty and reduced restrictions on markets. Peasants attacked estates and burned papers documenting the status of aristocrats. In 907, the Tang dynasty collapsed and several small states fought for power until the Zhao brothers established the Song dynasty in 960.

Under the Song dynasty, a landed gentry emerged that outnumbered the nobility working for the emperor. Markets expanded and connected China to global trade networks. In the 12th century, the Jurchen invaded northern China and established their own dynasty, while the Song continued to rule in the south. The Mongol Empire invaded China in the 13th century and established the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Mongols engaged in international trade, but their anti-commercial policies reduced domestic commerce.

The Yuan dynasty was overthrown in 1368 after being weakened by disease and rebellions and the Ming dynasty was founded. The first Ming emperor opposed the merchants and promoted a society based on agriculture and self-sufficiency. In 1644, the Manchus overthrew the Ming dynasty and established the Qing dynasty. In 1793, the British sent a diplomatic mission to China to establish trade relations. The Qianlong emperor agreed to open a port for the British at Guangzhou but refused to give them access to all of China's ports.[10]

Semi-colonial and semi-feudal society (1840–1949)

The era of semi-colonial and semi-feudal society was divided into two parts: The Old Democratic Revolution, which began with the First Opium War in 1840 and ended with the May 4th Movement in 1919, and the New Democratic Revolution, which lasted until the founding of the People's Republic in 1949. This 109-year period is also know as the "century of humiliation".[9]

Old Democratic Revolution period (1840–1919)

The Old Democratic Revolution was a period of establishing western "democracy" and dismantling feudalism, which is where it gets its name from. Rather than being a revolutionary movement by the people of China, it was a revolutionary change caused by the invasion and occupation of China by western powers. It began with the First Opium War when the feudal Qing dynasty tried to restrict the drug trade of opium in China. The United Kingdom, and later the United States of America, responded by declaring war on China.[9]

The conditions during this occupation were terrible. Notably in the British settlement of Shanghai, signboards were hung up outside parks prohibiting Chinese and dogs inside. The occupying powers forced local Chinese to carry them from place to place, and they also engaged in foot binding.[9]

New Democratic Revolution period (1919–1949)

The New Democratic Revolution was a revolution by the people of China against the weak Qing dynasty and the occupying Western powers. It is known as a democratic revolution because it still accepted the basic ideology of Western capitalism, but it was different in that it rejected colonialism and was fought by the people themselves. This revolution successfully brought down the Qing dynasty and established the Republic of China, but this state was even weaker than the Qing dynasty and most of the country was now ruled by warlords.[9]

At that time, China was one of the poorest societies in the world, plagued by starvation and feudal oppression. The vast majority of the population was engaged in subsistence agriculture, and a survey on the causes of death conducted in 1929-31 revealed that more than half of all deaths were caused by infectious diseases.[12] Famines were widespread and severe periods of hunger were lived by many Chinese peasants. During this period, China also suffered from illiteracy and high inequality. Estimates from this period suggest that, landlords and rich peasants taken together typically owned upward of half the land even though their share in the population typically did not exceed 10 percent. Poor peasants and agricultural labourers who owned little to no land formed the majority of the population.[13]

Educational standards during this period were terrible, if not inexistent. In 1949, more than 80 per cent of China's population was illiterate. Enrollment rates in primary and middle schools were abysmal: 20 and 6 per cent, respectively.[14] In addition, women's rights were highly curtailed and patriarchal norms were widespread, and this culture kept growing as Kuomintang rule took root in the Taiwan province.[15]

In 1925, the Empire of Japan and the U.K. sent troops to assist warlords in northern China. In 1926, the Northern Expeditionary Army of the CPC and Kuomintang defeated the warlords in Hebei province. On 1927 March 27, workers established a commune in Shanghai, which was crushed by Chiang Kai-shek when the Kuomintang turned against the CPC. At this point, the CPC organized an uprising of 30,000 led by Zhou Enlai and Zhu De against the nationalist forces. In October 1927, Mao was sent to Hunan and organized the first revolutionary base in the Jinggang Mountains. Zhu De joined Mao's forces and they repelled three attacks from the Kuomintang between 1928 and 1931. The Chinese Red Army soon grew to 100,000 people.[16]

On 1931 September 18, Japanese forces attacked the northeastern city of Shenyang. The Kuomintang's army withdrew from the area and did not resist the Japanese. In 1932, a nationalist army of 500,000 was defeated by the Red Army. In October 1933, Chiang Kai-shek mustered a force of a million troops, forcing the CPC and Red Army to flee west to Zunyi in the Long March. At the party conference in Zunyi in 1935, Mao's military line was established and opportunists were removed from power. By the end of the Long March, the Red Army's forces had dropped from 300,000 to 30,000.[16]

First Generation (1949–1976)

The first generation of leadership covers the extent of time that Zhou Enlai was the premier of the PRC. Mao Zedong was extremely influential in Chinese politics at this time, but he held the office Chairman of the PRC for only 9 years. For the rest of this 27 year long period, Mao Zedong was the General Secretary of the CPC. This generation was mainly characterized by Mao Zedong's political theory now known as Mao Zedong Thought.[17]

The first generation marks the founding of the People's Republic of China, an event captured on film.[18] The newly victorious socialist government promoted remarkable changes in Chinese society: establishing land reform, providing equal rights for women, seeing through campaigns for disease prevention and decreasing infant mortality.[12]

In 1958, China tried to end the U.S. occupation of Taiwan Province but had to retreat when the USA sent its nuclear-armed Seventh Fleet.[19]

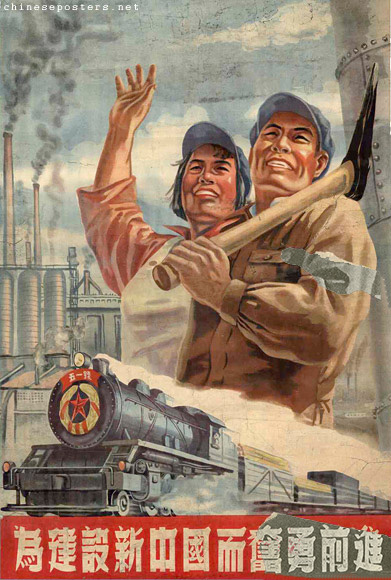

Industrialization and collectivization

The land reforms led to the destruction of feudal relations of production in agriculture, leading to virtually universal access to land and a dramatic reduction in poverty and hunger.[13] Education also improved dramatically in this period. During the 1950s, investments in primary and secondary school infrastructure increased considerably, and dramatic increases in attendance followed. Primary school enrollment rates rose to 80% by 1958 and to 97% by 1975, and secondary school rates increased to 46% by 1977.[14]

During this period, China's growth in life expectancy ranks as among the most rapid sustained increases in documented global history,[14][20] mainly because of the socialist government's radical commitment to the elimination of poverty and to improving living conditions of the people; an effort which has brought the elimination of widespread hunger, illiteracy, and ill health, remarkable reduction in chronic undernourishment and child mortality, and a dramatic expansion of longevity.[21] Systematic efforts to vaccinate the population against polio, measles, diphtheria, whooping cough, scarlet fever, cholera and other diseases were rapid and reputedly successful, virtually eradicating smallpox within the span of only three years.[14]

Great Leap Forward

Even though China achieved many positive changes in society, the first generation has experienced problems in their governance, most notably during the Great Leap Forward, which was a colossal failure, contributing to the Great Chinese Famine, which had major long-term effects on health and economic development in China, leading to reduced population height, and having a negative impact on labor supply and earnings of famine survivors.[22]

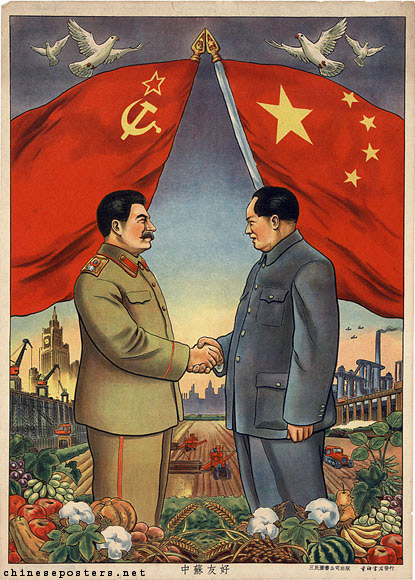

Sino-Soviet split

In the 1970s, China had an opportunistic foreign policy and frequently sided with the United States against the Soviet Union. It supported the Greek CIA[23] junta and Pakistan's war against Bangladesh and quickly recognized Pinochet's dictatorship in Chile.[24]

Cultural Revolution

Another campaign, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution resulted in overzealous local cadres taking the situation out of control, destroying sites of heritage and recklessly denouncing people in their community.[citation needed]

Second Generation (1976–1992)

The second generation of leadership covers the extent of time that Deng Xiaoping was influential in Chinese politics. Deng Xiaoping only held two positions of power during this time: Chair of the Central Military Commission of the PRC for four years, and Chair of the Central Military Commission of the CPC for 8 years. For the rest of this 16 year long period, Deng Xiaoping held no positions of power but was still considered the most influential figure in Chinese politics. This generation was mainly characterized by the development of Socialism with Chinese characteristics.[25]

The Reform and Opening Up programs introduced in this period produced impressive results. The Chinese economy saw a rapid expansion in both investment and consumption, rapid rises in both productivity and the wage rate, and rapid increases in job creation, which provided the necessary material conditions for broader social development, including the reconstruction of a publicly-funded healthcare system and acceleration of the process of urbanization.[26]

Inspired by Gorbachyov in the Soviet Union, Zhao Ziyang and his right-opportunist clique attempted to restore capitalism in the late 1980s.[27] The CIA and its cut-out, the NED, attempted a color revolution in 1989 and lynched unarmed PLA soldiers before being defeated.[28][29][30]

Third Generation (1992–2002)

The third generation of leadership covers the extent of time that Jiang Zemin was president of the PRC.[31] It was mainly characterized by Jiang Zemin's political theory known as the Three Represents.[32]

The Three Represents theory refers to the following:

- Representing the development trend of China’s advanced productive forces.

- Representing the orientation of China's advanced culture.

- Representing the fundamental interests of the overwhelming majority of the Chinese people.

Fourth Generation (2002–2012)

The fourth generation of leadership covers the extent of time when Hu Jintao was the president of the PRC and Wen Jiabo was premier. It was mainly characterized by Hu Jintao's political theory known as the scientific outlook on development.

Fifth Generation (2012–present)

The fifth generation of leadership covers the extent of time that Xi Jinping has been the president of the PRC, and that Li Keqiang has been the premier.[33] A key component of Xi's leadership is his administration's ongoing crackdown and cleaning out of CIA and other capitalist orgs penetration of the CPC and wider Chinese society.[34]

The biggest project of the fifth generation of leadership has been the Belt and Road Initiative. Other endeavors made during this generation include the Chinese Space Station, the Two Centennial Goals, and Green Development.

The main political contribution made during the fifth generation has been Xi Jinping Thought but other contributions have been made such as the Core Socialist Values and the Chinese Dream.

Administrative divisions

China has 34 province-level divisions: 23 provinces, 5 autonomous regions, 4 municipalities directly under the Central Government, and 2 special administrative region.[35]

Pro-worker economy

China operates what it calls Socialism with Chinese Characteristics, often referred to as the Socialist market economy by Chinese leaders.[36] In this system, China maintains state ownership of large industries and those that they deem vital to China's security while facilitating a market driven development of medium and small enterprises. Firms that would otherwise be monopolies in China are ran as what is called a State Owned Enterprise (SOE). SOE's often participate in markets and sometimes function much like a private firm with the key difference being China controls strategic resources such as rare earth minerals as well as silicon chips, which are both valuable to high-technology industries.[37]

Factory workers in China (in both the public and private sector) have the ability to join workers' congresses, which grant them control over wage adjustments, supervision of leadership and election of the factory director.[38][39][40] SOE congresses have decidedly more power than private enterprises. In 2005, a study released regarding the influence of workers' congresses and Chinese unions analyzed the effects of companies that had unions or no unions. When surveyed, the worker satisfaction along the metrics of greater worker rights, greater wages and greater abilities to settle conflicts in favour of workers. It was found that generally speaking, worker satisfaction was higher than in companies without them. And the same study claims around 80% of all companies have some form of workers union on board. Worker's participation however, is not mandatory in these unions and those who do not wish to unionize are not required to have a union.[41] A similar 2004 study found that these workers' congresses were able to dismiss managers when they failed to get more than 60% votes of confidence, and that it was possible for these unions to significantly improve health and safety conditions, or to fairly distribute new housing benefits.[42]

In 2012, the number of unions in SOEs were 88.1% and in non-SOEs to be around 85.5%. It also states that within Chinese companies 32.7% of employee representatives at the company and plant level are nominated and elected directly from employees, while 61% of them are nominated by the Party committees and elected by employees. The same study finds that workers' congresses are positively associated with better health and safety, and more likely to report issues or flaws within company structure, as well as a useful consultation method that better leveraged worker voices towards the higher ups.[43] In a study done by the OECD in 2013, survey of employment protection legislation found that China’s legislation ranked as the most protective of the forty-three countries surveyed.[44] The CPC has therefore made tremendous efforts to meet the demands of local protests and strikes as well as hold local governments accountable for causing or mishandling protests that spin out of control. Chinese workers have successfully organized collective action to get local governments, and the courts as mentioned above, to help accommodate their claims, most notably getting payment for wage arrears.[45] Similarly, a study in 2009 found that more often than not, the arbitration tribunals in mainland China are biased in favor of employees suing their employers. Because arbitration tribunals are sympathetic towards employees-who are traditionally seen as the weaker party-they will sometimes overlook acontract violation by the employee. In addition, sometimes tribunals assume that companies can bear the financial losses more readily than employees. Therefore, more often than not, employees win in arbitration or in court based on prejudice in their favor.[46]

The book A New Deal for China's Workers (released in 2016) states that,[47]

"In enacting the LCL, and in doubling down on its employment protections by restricting the use of labor dispatch, China is swimming against both a modest liberalizing current in parts of the developed world and deeper trends toward declining job tenure, splintering of work organizations, outsourcing of production, and contingent work arrangements. The continuing slide from long-term employment within integrated firms toward a “gig” economy, though celebrated by some, has potentially dire consequences for workers who risk losing the entire panoply of rights, protections, and benefits that twentieth-century reforms had attached to the employment relationship. But China is seeking to defy that trend, and to shore up job security and stability."

Though trying to portray the CPC in a negative light here, it still admits that the CPC opposes and seeks to ensure better job security and stability compared to the Capitalist nations of the West. Defying a gig economy and seeking to double down on employment protection has done far more than the rest of the "developed world" in securing and defending the rights of the working class.

China also has a vibrant worker co-operative model of ownership. Worker co-operatives are trading enterprises, owned and run by the people who work in them, who have an equal say in what the business does, and an equitable share in the wealth created from the products and services they provide, with 48% of all rural households in China being apart of a co-operative.[48] In 2017, there were 30,281 primary (village-level) supply and marketing cooperatives (SMCs), 2,402 country-level federations of SMCs, 342 city-level federations of SMCs, 32 provincial-level federations of SMCs, 21,852 cooperative enterprises and 280 cooperative institutes represented by ACFSMC (All China Federation of Supply and Marketing Cooperatives). There were 3.4 million employees in all SMCs represented by ACFSMC.[49] About 95% of towns and villages have a SMC as of 2019, compared to 50% a mere 6 years ago.[50] The cooperative sector continues to grow, China's supply and marketing system will realize sales of agricultural products of 2.7591 trillion yuan and daily necessities of 1.4925 trillion yuan, a year-on-year increase of 24.3% and 17.1% respectively. A recruitment notice stated that in 2023, the All-China Federation of Supply and Marketing Cooperatives plans to take the examination and recruit staff from the agency. Outstanding young people who are interested in joining the supply and marketing cooperatives are welcome to apply for the examination.[51]

China also has great democratic management in the workplace, with positive associations with workers' hourly wages, fringe benefits, and firms' labor productivity on average, suggesting that it is not merely ‘window-dressing’ as perceived by conventional wisdom.[52] Chinese workers have also had higher wage increases, doubling between 2008 and 2019, compared to emerging G20 countries with a 3.5-4.5% annual growth. And in advanced G20 countries with 0.4-0.9% annual growth.[53] Chinese workers having greater rights even extend to the ability to imprison their own boss in their office, with the police intervening on behalf of the workers.[54]

As of January 2023, The People's Republic of China has an overall historic unemployment rate of around 4-5%,[55] compared to the Statesian historic unemployment rate of around 5-6%.[56] This is high in comparison to the economy of, for example, the USSR, which generally had stable employment opportunities for young workers, and also had an unemployment rate of about 1%.[57]

Although GDP growth was at its peak in the 1960s, China experiences consistent GDP growth, and China outpaces the US in terms of GDP growth.[58]

Mode of production

Currently, China is in the primary stage of socialism. This is a stage which is expected to last until the 100th anniversary of the People's Republic of China, in 2049, and this stage is intended to unleash the productive forces of China to the point where socialism is superior in terms of productivity in contrast to the capitalist mode of production.[59]

Governance

Healthcare

In the Mao period, China built one of the developing world's most robust public healthcare systems, based on rural primary care, barefoot doctors, and regular mass campaigns, known as "patriotic health campaigns." Since the beginning of the reform period, China's healthcare system has gone through a number of phases. After an unfortunate period of regression and privatization, China has spent the last decade making rapid progress towards a new universal healthcare system. A 2020 study in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) summarizes many of the goals and programs of China's recent health reforms:

Priority was given to expanding the scope and health service package of the basic insurance coverage, improving provider payment mechanisms, as well as increasing the financing level, fiscal subsidies and reimbursement rates. [...] The government has increased investment in primary care, with initiatives that include strengthening the infrastructure of primary healthcare (PHC) facilities, expanding human resources for primary care through incentives and supporting projects, establishing a general practitioner system and improving the capacity of PHC personnel through training and education, such as general practice training and continuous medical education programmes. [...] The ‘equalization of basic public health services’ policy implemented the national BPHS programme and the crucial public health service (CPHS) programme. [...] This policy seeks to achieve universal availability and promote a more equitable provision of basic health services to all urban and rural citizens.[60]

The study goes on to note that China has made significant progress towards meeting its reform goals, and building a developed and equitable universal healthcare system:

During the past 10 years since the latest round of healthcare reform, China made steady progress in achieving the reform goals and UHC [i.e. universal health coverage].

Another paper, also from the BMJ, summarizes the recent improvements in China's health outcomes, as well as access to, and cost of, healthcare:

The results include the following: out-of-pocket expenditures as a percentage of current health expenditures in China have dropped dramatically from 60.13% in 2000 to 35.91% in 2016; the health insurance coverage of the total population jumped from 22.1% in 2003 to 95.1% in 2013; the average life expectancy increased from 72.0 to 76.4, maternal mortality dropped from 59 to 29 per 100 000 live births, the under-5 mortality rate dropped from 36.8 to 9.3 per 1000 live births, and neonatal mortality dropped from 21.4 to 4.7 per 1000 live births between 2000 and 2017; and so on.[61]

In short, while China's healthcare system is not perfect, it is certainly moving in the right direction. As with many other aspects of China's socialist construction, this provides a model for other developing nations; according to the aforementioned BMJ study:

The lessons learnt from China could help other nations improve UHC in sustainable and adaptive ways, including continued political support, increased health financing and a strong PHC system as basis. The experience of the rapid development of UHC in China can provide a valuable mode for countries (mainly LMICs) planning their own path further on in the UHC journey.

This is another benefit of China's rise to prominence on the world stage. China demonstrates to the world that it is possible for a desperately poor country to rise from poverty, develop its economy, and meet the needs of its people.

Democracy and popular opinion

Polls conducted by Western researchers have consistently found that the Chinese people have a high level of support for their government, and for the Communist Party. A 2020 analysis by the China Data Lab (based at UC San Diego) found that support for the government has been increasing as of late.[62] Similar results were found in a 2016 survey done by Harvard University's Ash Center:

The survey team found that compared to public opinion patterns in the U.S., in China there was very high satisfaction with the central government. In 2016, the last year the survey was conducted, 95.5 percent of respondents were either “relatively satisfied” or “highly satisfied” with Beijing. In contrast to these findings, Gallup reported in January of this year that their latest polling on U.S. citizen satisfaction with the American federal government revealed only 38 percent of respondents were satisfied with the federal government.[63]

It is worth noting that the Chinese people are significantly less satisfied with local government than they are with the central government. Still, these results disprove the common notion that the Chinese people are ruled by an iron fisted regime that they do not want. Indeed, one official from the Ash Center noted that their findings "run counter to the general idea that these people are marginalized and disfavored by policies." As he states:

We tend to forget that for many in China, and in their lived experience of the past four decades, each day was better than the next.

In addition, most Chinese people are satisfied with the level of democracy in the PRC. A 2018 study in the International Political Science Review notes that "surveys suggest that the majority of Chinese people feel satisfied with the level of democracy in China." However, the study notes that "people who hold liberal democratic values" are more likely to be dissatisfied with the state of democracy in China. By contrast, those who hold a "substantive" view of democracy (i.e. one based on the idea that the state should focus on providing for the material needs of the people) are more satisfied.[64]

While the Chinese government contains authoritarian elements, it also has elements of genuine democracy. An example of this may be found in the National People's Congress, China's primary legislative body. While Western media has typically labeled the NPC as a simple rubberstamping body for the Central Committee, the facts indicate that this is not entirely true. A 2016 study in the Journal of Legislative Studies found that the NPC "is no longer a minimal or ‘rubber-stamp’ legislature," noting that "the NPC does play an important role in the whole political system, especially in legislation, though the NPC has typically been under the control of China's Communist Party."[65]

Many of the other claims surrounding authoritarianism in China are highly overblown, to say the least. For instance, an article in Foreign Policy (the most orthodox of liberal policy journals) notes that the Chinese social credit system was massively exaggerated and distorted in Western media. An article in the publication Wired discusses how many of these overblown perceptions came to be. None of this is to suggest that China is a perfect democracy, with zero flaws; it certainly has issues relating to transparency, treatment of prisoners, etc. That being said, it is far from the totalitarian nightmare that imperialist media generally depicts it as being.

Public ownership

See main article: Socialist market economy

Contrary to the popular perception that China's growth has been the result of a transition to capitalism, the evidence shows that public ownership continues to play a key growth-driving role in the PRC's economy. According to the aforementioned 2020 study in the Review of Radical Political Economics, "strategic industries, which Lenin called 'the commanding heights of economy,' are still state-owned and have played a very important role in China’s economic development."[66] The author notes that "after decades of market reform, China’s state sector, rather than disappearing or being marginalized, has become a leader in strategic sectors and the driver of its investment-led growth." To learn more, we would recommend the book The Basic Economic System of China, which goes into this issue in much more depth.[67]

Even after the economic reforms, China's public ownership sector remained great, according to the paper "China’s Collective and Private Enterprises: Growth and Its Financing" by Shahid Yusuf, during 1985-1991, on average only around 7.1 % of the Industrial Sector was actually private (started by entrepreneurs and foreign businesses).[68] And during 1991, the national industrial sector only had around 11.41% being truly private.[69]

In the University Paper, Is China still Socialist by Khoo Heikoo, their research goes into detail of the market share of the economy. In 2010, at least 94% of all financial capital and revenue is owned by SOE's out of 150 largest companies in China.[70] In the University paper, The Rise of the Investor State: State Capital in the Chinese Economy by Hao Chen and Meg Rithmere discusses how state shareholders can influence the private sector. With the overall ownership of investment firms in 2017 being 80.9% central state owned, 13.7% local state owned and only 4.67% being truly private. The paper also goes on to state:[71]

"The state’s role as owner of firms has narrowed to include a set of large, national champion firms at the central level, but the deployment of state capital has morphed form rather than abated. As we have shown, the state invests broadly in the private sector in a number of forms, a fact that complicates the “state versus private” dichotomy that has dominated the study of China’s political economy during the reform era. Further, the deployment of state capital into the wider economy has accompanied a change in the structure of the state; hundreds of shareholding firms, large and small and owned by local and central levels of the state, now interface extensively with private firms, can intervene with ease in stock markets, and appear to constitute new agents in the execution of the CCP’s overall economic policy."

The Ascendency of State-owned Enterprises in China: development, controversy and problems by Hong Yu also states:[72]

"In terms of total sales revenue of China’s top 100 enterprises in 2011, the SOEs accounted for around 90%. The state sector remains the driving force behind economic development in China. All the big commercial banks in China are SOEs. More importantly, given the fact that township and village enterprises (TVEs) owned by local governments belong to the state sector but are not regarded as SOEs, and a large number of entities operating inside and outside of China are actually owned or controlled indirectly via SOEs’ subsidiaries, the true size of the SOEs is unknown. Their influence is far greater than official statistics suggest. Woetzel’s study also demonstrates that many firms, which were partially privatized but with the state remaining as a majority shareholder, have not been counted in the SOE category in official statistics."

In 2014, China's top 500, 300 are SOEs, accounting for 60 percent. The operating revenues of these SOEs account for 79.9 percent of the total 56.68 trillion yuan, while total assets account for 91.2 percent, out of the total 176.4 trillion yuan. The total profit of these SOEs account for 83.9 percent out of the total 2.4 trillion yuan[73] In 2006, The report revealed that 349 enterprises in the list were state owned, accounting for nearly 70 percent of the total. Their combined assets reached 39 trillion yuan (4.87 trillion US dollars) at the end of 2005, accounting for 95 percent of the total. It showed that state-owned economy remained dominant and controls the leading industries in the national economy.[74] Even in the 1990s after Reform and Opening Up, the OECD Agricultural Outlook/June - July 1999 discuss how the state maintains control of the agricultural sector

“Before 1980, government central planning dominated domestic grain marketing. The government’s Grain Bureau purchased, transported, stored, milled, and retailed all grain leaving the farm. Then in the 1980’s and early 1990’s, open markets became increasingly important as the government was no longer the sole purchaser and many provinces began phasing out a ration system that allowed urban consumers to purchase grain at low fixed prices (AO March 1997). But current grain policy, initiated in 1998, led to a reversal of the use of open markets for domestic distribution and an increase in government intervention in grain production and marketing. This relatively recent return to intervention in the domestic market has led to higher grain output and reduced demand for imports.”

And then proceeds to state in OECD Agricultural Policy Reform in China 2005 [75]p6 states

“Total support to China’s agricultural sector reached USD 41 billion per year in 2000-2003 which is equivalent to 3.3% of China’s GDP in this period. This percentage is much higher than the OECD average and suggests a relatively high burden of agricultural support on the Chinese economy.”

Agriculture in China whilst dominated by private family production units at the micro level is dominated by state purchase and distribution at the macro level. This ensures that China is able to feed itself and that supplies of essential grains reach the entire national consumer market. Imports and exports of grain are determined by the state and implemented by its organizations, thus contrary to appearances, Chinese agriculture is dominated by the state. And in 2009, Derrick Scissors of the Heritage Foundation lays the issue to rest in an article called “Liberalization in Reverse.” He writes:

"Examining what companies are truly private is important because privatization is often confused with the spreading out of shareholding and the sale of minority stakes. In China, 100 percent state ownership is often diluted by the division of ownership into shares, some of which are made available to nonstate actors, such as foreign companies or other private investors. Nearly two-thirds of the state-owned enterprises and subsidiaries in China have undertaken such changes, leading some foreign observers to relabel these firms as “nonstate” or even “private.” But this reclassification is incorrect. The sale of stock does nothing by itself to alter state control: dozens of enterprises are no less state controlled simply because they are listed on foreign stock exchanges. As a practical matter, three-quarters of the roughly 1,500 companies listed as domestic stocks are still state owned. "[76]

He also goes onto further elaborate sectors of the economy that the CPC have not once relinquished public ownership of key sectors of industry.

"No matter their shareholding structure, all national corporations in the sectors that make up the core of the Chinese economy are required by law to be owned or controlled by the state. These sectors include power generation and distribution; oil, coal, petrochemicals, and natural gas; telecommunications; armaments; Aviation and shipping; machinery and automobile production; information technologies; construction; and the production of iron, steel, and nonferrous metals. The railroads, grain distribution, and insurance are also dominated by the state, even if no official edict says so."[76]

Another way the CPC retains public ownership is through the banking system. The People’s Bank of China (PBC) highlights one of the most important ways in which the CPC uses the market system to control private capital and subordinate it to socialism. Far from functioning as a capitalist national bank, which prioritizes facilitating the accumulation of capital by the bourgeoisie, “this system frustrates private borrowers.”[76]

"the state exercises control over most of the rest of the economy through the financial system, especially the banks. By the end of 2008, outstanding loans amounted to almost $5 trillion, and annual loan growth was almost 19 percent and accelerating; lending, in other words, is probably China’s principal economic force. The Chinese state owns all the large financial institutions, the People’s Bank of China assigns them loan quotas every year, and lending is directed according to the state’s priorities."

The CPC floods the market with public bonds, which has a crowding-out effect on private corporate bonds that firms use to raise independent capital. This also renders state bonds far more valuable than private bonds and the credit deterioration of non-state bonds is worse than state bonds. State Owned Enterprises receive much more preferential treatment from the government due to this model of flooding state bonds and far more valuable bonds into the market, with comparable private bonds declining in terms of value and being unable to compete. In 2018, this is clearly demonstrated after the implementation of more regulations on the shadow banking market, leading to investors flocking towards much more valuable State bonds over private ones. This inevitably creates a feed back look where State bonds have a "premium" and are objectively more valuable than private ones.[77] By harnessing supply and demand in the bond market, the PBC prevents private firms, domestic or foreign, from accumulating capital independently of socialist management.

Although modern China has an expansive market system, the CPC uses the market to both secure and advance socialism. Rather than privatizing major industries, as is often alleged by detractors, the state maintains a vibrant system of socialist public ownership that prevents the rise of an independent bourgeoisie.

The capitalist Australia-based Center for Independent Studies (CIS) has also published a July 2008 article that says that those who think that China is becoming a capitalist country “misunderstand the structure of the Chinese economy, which largely remains a state-dominated system rather than a free-market one.” The article elaborates:

"By strategically controlling economic resources and remaining the primary dispenser of economic opportunity and success in Chinese society, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is building institutions and supporters that seem to be entrenching the Party’s monopoly on power. Indeed, in many ways, reforms and the country’s economic growth have actually enhanced the CCP’s ability to remain in power. Rather than being swept away by change, the CCP is in many ways its agent and beneficiary."[78]

The true nature of the private sector is actually quite small once you take into account it's breaking down. In 2005, the private sector is dominated by small sized enterprises, only 5 per cent of private enterprises employ more than 500 and only 2% more than 1000 workers. Contrast this with the state sector where 80% of workers work in companies employing over 500 workers. The number of private companies rose from 90,000 in 1989 employing 1.4 million workers, to 3.6 million companies in 2004 employing 40 million workers. 74% of private companies originated as new start ups, 7% are privatized state owned companies, 8% are privatized rural collectives and 11% are privatized urban collectives. The average income of an entrepreneur is $6600 US per year (2002 figures) this gives an idea of the small scale of the overwhelming majority of private sector enterprises in China.[79]

Though some may worry about the existence of foreign enterprise in China, once we look deeper into how these manifest, these worries are quickly aleviated.

"Foreign investment was regulated to make it compatible with state development planning. Technology transfer and other performance requirements ― conditions attached to foreign investment to make sure that the host country gets some benefit from foreign investment, such as the use of locally produced inputs, or the hiring of local managers ― were common and are still an issue of contention with the United States today.”[80]

"in order to gain access to the vast and rapidly growing China market, Boeing was required to assist the main Chinese aircraft manufacturer in Xian to successively establish a capacity to produce spare parts and then manufacture whole sections of aircraft, and finally to assist in the development of a capacity to produce complete aircraft within China. In order to gain the right to invest in car production in China, Ford Motor Company was required to first invest for several years in upgrading the technical capacity of the Chinese automobile spare parts industry through a sequence of joint ventures.”[81]

And of course, for a good example would be McDonalds, where it remains a Joint-Venture with majority CPC ownership. 52% owned by CPC, 20% by McDonalds and 28% by Carlyle.[82] China also bars many foreign companies from participating in the Chinese market. As a result, companies need to enter the market through other means, such as setting up a wholly foreign-owned enterprise (WFOE) or forming a joint venture with a Chinese business partner. It is also alleged that Chinese Joint-Ventures and Chinese companies tend to steal IP and technologies from these foreign companies, as demonstrated in the above quotes. And many foreign investors have also stated that there are no legal protections for these foreign companies and Chinese attorneys will lobby in favour of the state, this indicates that foreign companies clearly do not run amuck in China. Many foreign investors have complained about the lack of freedom of voice in the Chinese market, with the state being the ultimate deciding factor in many cases.[83]

The TVE's (Township and Village Enterprises) have been described as "private". This collectively owned sector grew rapidly - in 1978 there were 1.5 million such enterprises, by 1995 there were 22 million. In 1978 they employed 28 million people, by 1995 128 million.[84] While they have been claimed to be private, in reality, the CPC legally defines TVE's as

"The term "township enterprises" as mentioned in this Law refers to all kinds of enterprises established in townships (including villages under their jurisdiction) that are mainly invested by rural collective economic organizations or farmers and undertake the obligation to support agriculture.

The term "investment-based" mentioned in the preceding paragraph refers to rural collective economic organizations or farmers investing more than 50 percent, or less than 50 percent, but can play a controlling or actual dominating role.

A township enterprise that meets the conditions for an enterprise legal person shall obtain the qualification of an enterprise legal person according to law."[85]

This tells us that despite being claimed to be private, the village are still the collective owners of the TVE's. Thus making it a Cooperative sector of the economy.

Growth and poverty reduction

According to a 2019 report from Philip Alston (UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights):

China’s achievements in alleviating extreme poverty in recent years, and in meeting highly ambitious targets for improving social well-being, have been extraordinary. [...] Over the past three decades, and with particular speed in recent years, China has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. This is a staggering achievement and is a credit to those responsible.[86]

Similarly, a 2020 study in the China Economic Review notes that income growth has been "widely shared nationwide," resulting in "substantial, ongoing rural poverty reduction" throughout the country. A major milestone was reached with the recent announcement (acknowledged in Western media outlets, such as CNN) that the last poverty-stricken counties in China have been delisted, "leaving no county in a state of absolute poverty countrywide."[87]

Malnutrition has continued to decline massively in China over the last several decades. According to the University of Oxford's Our World in Data project, China now has a lower rate of death from malnutrition than the United States,[88] as well as a lower rate of extreme poverty, despite having a significantly lower GDP-per-capita.[89]

Economic growth has also increased dramatically. According to a study from the National Bureau of Economic Research, "reforms yielded a significant growth and structural transformation differential. GDP growth is 4.2 percentage points higher and the share of the labor force in agriculture is 23.9 percentage points lower compared with the continuation of the pre-1978 policies."[90]

Foreign relations

In 2021, China signed a 25-year cooperation agreement with the Islamic Republic of Iran.[5]

Debunking myths

"Imperialism" and the Belt and Road Initiative

China is often accused of being an "imperialist" state, due primarily to its investments in Africa, as part of the Belt and Road Initiative. These critics ignore the actual views of the African people themselves, who overwhelmingly approve of China's role in their economic development.[91] In addition, the extent of Chinese involvement in Africa is smaller than often believed; according to a 2019 paper from the Center for Economic Policy Research, "China’s influence in Africa is much smaller than is generally believed, though its engagement on the continent is increasing. Chinese investment in Africa, while less extensive than often assumed, has the potential to generate jobs and development on the continent."[92]

A 2018 study in the Review of Development Finance also found that Chinese investment in Africa raises incomes in the African nations that receive the investment, in a similar way to foreign investments by other nations. The author state that these results "suggest that the win-win deal China claims when investing in Africa may hold, and Chinese investment contributes to growth in Africa. Put differently, Chinese investment is mutually beneficial for both China and Africa."[93]

Despite the Western media accusing China of "debt trap diplomacy," China gives loans at low interest rates and often allows countries to restructure or even never repay loans, unlike the neocolonial IMF.[94] China has forgiven tens of billions of dollars of debt held by African countries.[95] It has also forgiven 23 interest-free loans to 17 different countries.[94]

The economist Yanis Varoufakis discussed the topic in a recent lecture given at the Cambridge forum. He helpfully debunks a number of myths on the matter.

Censorship and the Great Firewall

Facebook was allowed in China up until the deadly 2009 riots in Xinjiang.[96] In the bigger picture, this is a response to the terroristic behavior of the NED.[97] Much like how communists are censored in the west, China is defending itself against the common imperialist tactic of color revolution.

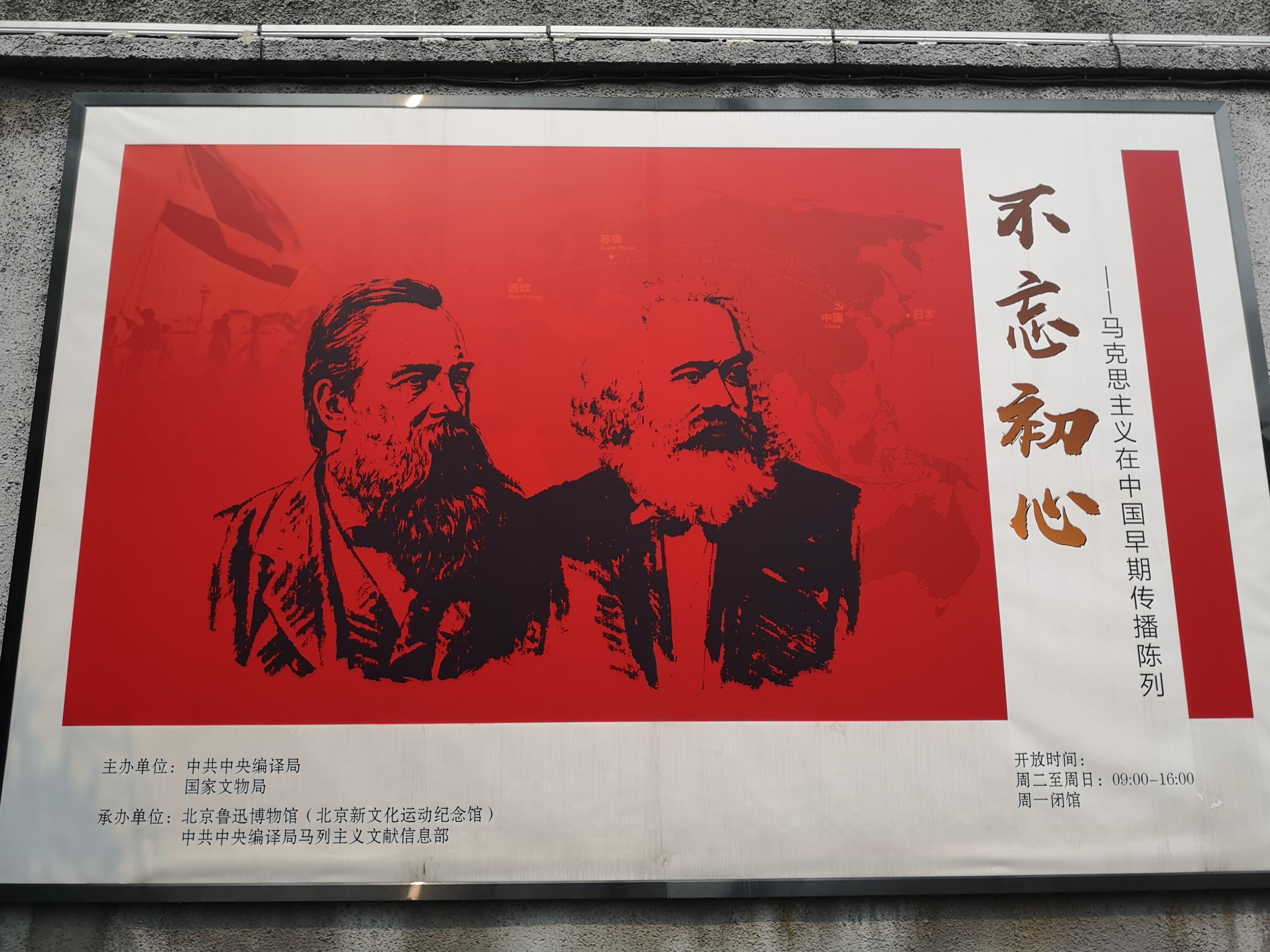

Abandoning of Marxism

In 2020, Xi Jinping gave a speech to the Politburo of the Communist Party of China, in which he made clear the continued importance that the CPC places on Marxist political economy. To quote:

Marxist political economy is an important component of Marxism, and required learning for our efforts to uphold and develop Marxism. [...] There are people who believe Marxist political economy and Das Kapital are obsolete, but this is an arbitrary and erroneous judgment. Setting aside more distant events and looking at just the period since the global financial crisis, we can see that many capitalist countries have remained in an economic slump, with serious unemployment problems, intensifying polarization, and deepening social divides. The facts tell us that the contradictions between the socialization of production and the private possession of the means of production still exist, but they are manifested in ways and show characteristics that are somewhat different.[98]

He goes on to list a number of principles guiding the implementation of Marxist political economy in the PRC:

First, we must uphold a people-centered approach to development. Development is for the people; this is the fundamental position of Marxist political economy. [...] Second, we must uphold the new development philosophy. Third, we must uphold and improve our basic socialist economic system. According to Marxist political economy, ownership of the means of production is the core of the relations of production, and this determines a society's fundamental nature and the orientation of its development. Since reform and opening up... we have stressed the importance of continuing to make public ownership the mainstay while allowing ownership of other forms to develop side by side, and made it clear that both the public and non-public sectors are important components of the socialist market economy as well as crucial foundations for our nation's economic and social development. [...] Fourth, we must uphold and improve our basic socialist distribution system. [...] Fifth, we must uphold reforms to develop the socialist market economy. [...] Sixth, we must uphold the fundamental national policy of opening up.

From this, it should be quite clear that Marxism (specifically Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought) retains a dominant role in the People's Republic of China, serving as the guiding ideology of the Communist Party.

Despite common misconceptions, class struggle (an important component of Marxism) has not been abandoned in China; billionaires go missing, are jailed or even executed for corruption, bribery and speaking out against the government.[99][100] In 2013, a private company started building luxury villas on protected land in the Qinling Mountains; Xi Jinping ordered the buildings destroyed to make room for parks and giant panda habitats.[101]

LGBT rights

See also: LGBT rights and issues in AES countries#People's Republic of China

Same-sex relationships are legal in China, although same-sex marriage and adoption are not currently legal. Same-sex couple married overseas can be named as each other’s “legal guardians”, a status considered fairly similar to a civil union.[102] Transgender individuals are legally allowed to receive healthcare and may legally change their gender marker after receiving sexual reassignment surgery. In recent years, transgender treatment facilities have become more available in China, including the opening of a clinic for the treatment of transgender minors in 2021, with both psychological help and hormone treatment available.[103]

Professor Li Yinhe of the Institute of Sociology under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences was quoted in a CGTN article as saying that the biggest challenge for the LGBT community in China is not anything imposed by law, but rather family pressure stemming from the "deep-rooted culture" that places high priority on family values and especially an emphasis on carrying on the family line.[104]

According to a 2020 report published in BMC Public Health, "For member of the Chinese LGBT community, the greatest source of pressure to conform to societal norms of sexuality and identity comes from family members—particularly parents." The report also found that "a higher level of economic development in provinces was associated with a decrease in discrimination, and we identified that every 100 thousand RMB increase in per capita GDP lead to a 6.4% decrease in discriminatory events perpetrated by heterosexuals" and that "The prevalence of this discrimination is associated with the economic development of the province in which it occurs."[105]

The 2021 short documentary film "A Day of Trans" (Chinese: 跨越性别的一天) explores the lived experiences of four Chinese transgender individuals across three generations, exploring their professional career paths, community involvement, social barriers, and their unique approaches to life as transgender individuals across the generations. It is directed by Yennefer Fang, a Chinese transgender independent filmmaker. It follows Liu Peilin, who was born in 1956, and started identify as a woman in her 40s. It also follows Mr. C, a 35-year-old transgender man, who became the public face in the fight for job equality in China in 2016 and who won a court case against his employer for discrimination for his gender identity. Finally, it follows two transgender artists who grew up during China's rapid economic growth. Fang said that she tries to observe the status of transgender people from an internal perspective and tries to dispel misconceptions through the documentary, including the perception that "transgenderism" is a contemporary, white, or bourgeois term.[106][107]

See Also

References

- ↑ Statista. [1]

- ↑ Investopedia. [2]

- ↑ "Western experts should understand China’s building of socialism from China’s perspective" (2022-01-16). Friends of Socialist China.

- ↑ Constitution of the People's Republic of China (PDF in English)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Nia Frome (2021-04-05). "China Has Billionaires" Red Sails. Archived from the original on 2022-11-29. Retrieved 2022-12-06.

- ↑ Laura Silver, Kat Devlin and Christine Huang (2020). Unfavorable views of China reach historic highs in many countries. [PDF] Pew Research Center.

- ↑ Rainer Shea. "Categorically Debunking the Claim that China is Imperialist" Orinoco Tribune. Archived from the original on 2021-11-28.

- ↑ Amendment to the Constitution of the People's Republic of China (Adopted at the Second Session of the Ninth National People's Congress and promulgated for implementation by the Announcement of the National People's Congress on March 15, 1999)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Bai Shouyi (2008). An outline history of China. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 9787119052960

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Ken Hammond (2021-09-13). "Beyond the sprouts of capitalism: China’s early capitalist development and contemporary socialist project" Liberation School. Archived from the original on 2022-04-28. Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- ↑ Mao Zedong (1939). The Chinese Revolution and the Chinese Communist Party: 'Chinese Society; The Old Feudal Society'. [MIA]

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 David Hipgrave (2011). Communicable disease control in China: From Mao to now. Journal of Global Health.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Robin Burgess (2005). Mao's legacy: Access to land and hunger in Modern China. The London School of Economics and Political Science. (PDF link)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Kimberly Singer Babiarz, Karen Eggleston, Grant Miller & Qiong Zhang (2015). An exploration of China's mortality decline under Mao: A provincial analysis, 1950–80.

- ↑ Norma Diamond (1975). Women under Kuomintang rule: Variations on the feminine mystique. University of Michigan. doi: 10.1177/009770047500100101 [HUB]

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Remembering the Chinese Revolution". Banned Thought. Retrieved 2022-05-14.

- ↑ The historic contribution made by the first generation of the party's central collective leadership to the creation of socialism with Chinese characteristics in the new era (Chinese: 党的第一代中央领导集体为新时期开创中国特色社会主义所作的历史性贡献)

- ↑ Mao Zedong 毛泽东 declares the Peoples' Republic of China 1949. YouTube. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ↑ Vijay Prashad (2008). The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World: 'Havana' (p. 109). [PDF] The New Press. ISBN 9781595583420 [LG]

- ↑ David Hipgrave, Yan Mu (2018). Health system in China. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-8715-3_42 [HUB]

- ↑ Amartya Kumar Sen (2006). Perspectives on the Economic and Human Development of India and China. Universitätsverlag Göttingen. ISBN: 978-3-938616-63-5

- ↑ Yuyu Chen, Li-An Zhou (2007). The long-term health and economic consequences of the 1959-1961 famine in China. Journal of Health Economics. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.12.006 [HUB]

- ↑ William Blum (1995). Killing Hope (p. 219). Monroe. ISBN 1567510523

- ↑ Vijay Prashad (2008). The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World: 'Tawang' (p. 174). [PDF] The New Press. ISBN 9781595583420 [LG]

- ↑ The whole process of the formation of the central collective leadership with Deng Xiaoping as the core. (Chinese: 邓小平为核心的中央领导集体形成始末)

- ↑ Dic Lo (2020). State-owned enterprises in Chinese economic transformation: Institutional functionality and credibility in alternative perspectives. Journal of Economic Issues. doi: 10.1080/00213624.2020.1791579 [HUB]

- ↑ J. Sykes (2022-12-24). "Red Theory: The achievements of socialism in China" Fight Back! News. Archived from the original on 2023-01-23. Retrieved 2023-02-05.

- ↑ Tom (2021-06-04). "The Tian'anmen Square 'Massacre': The West's Most Persuasive, Most Pervasive Lie" Mango Press. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ↑ Brian Becker (2014-06-13). "Tiananmen: The Massacre that Wasn’t" Liberation School. Archived from the original on 2022-01-02. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- ↑ Milton James (2020-07-08). "1989 Tiananmen Square "Student Massacre" was a hoax" Critical Social Work Publishing House. Archived from the original on 2022-03-21. Retrieved 2022-06-05.

- ↑ The top priority of the third generation of collective leadership.(Chinese: 第三代领导集体的当务之急)

- ↑ What is the scientific meaning of "Three Represents"? (Chinese:“三个代表”的科学含义是什么?)

- ↑ The fifth generation of collective leadership in China (Chinese: 中国第五代领导集体)

- ↑ China Used Stolen Data To Expose CIA Operatives In Africa And Europe [3]

- ↑ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China Administrative Division System

- ↑ Sam-Kee Cheng (2020). Primitive socialist accumulation in China: An alternative view on the anomalies of Chinese “capitalism”. doi:10.1177/0486613419888298 [HUB]

- ↑ https://youtu.be/jlShNCKx8rw

- ↑ https://www.peoplesworld.org/article/china-and-russia-have-workers-councils-but-not-chattanooga/

- ↑ https://www.reddit.com/r/communism/comments/d1u77y/workers_councils_in_china/

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20220610093819/https://twitter.com/isgoodrum/status/1043159032935006208

- ↑ ZHU XIAOYANG AND ANITA CHAN - Staff and Workers’ Representative Congress An Institutionalized Channel for Expression of Employees’ Interests?

- ↑ The Internal Politics of an Urban Chinese Work Community: A Case Study of Employee Influence on Decision-Making at a State-Owned Factory

- ↑ The perceived effectiveness of democratic management, job performance, and citizenship behavior: evidence from a large Chinese state-owned petrochemical company- Fuxi Wang

- ↑ Curtis Milhaupt and Wentong Zheng, “Beyond Ownership: State Capitalism and the Chinese Firm,” Georgetown Law Journal 103 (2015): 665-717.

- ↑ Su and He, “Street as Courtroom: State Accommodation of Labor Protests in South China.”

- ↑ Joanna Law, Employers, Prepare for Tribunal Trouble, CHINA LAW & PRACTICE, Feb. 2009

- ↑ Conclusion, Page 220 - A New Deal for China’s Workers? 2016017881, 9780674971394

- ↑ How Village Co-Ops are remapping China's rural community

- ↑ China, #CoopsForDev

- ↑ Xi Jinping turns to Mao Zedong era system to get rid of poverty

- ↑ Afternoon inspection: Supply and marketing cooperatives come back? - Zaobao.sg

- ↑ What does democratic management do in Chinese workplaces? Evidence from matched employer–employee data

- ↑ ILO- International Wage Report

- ↑ Held Hostage: Entrepreneurs' uneasy over Chinese government inaction - Forbes

- ↑ China unemployment rate 1991 - 2023, macrotrends

- ↑ US Unemployment Rates 1991 - 2023, macrotrends

- ↑ "Soviet Union Economy - 1991" (1991). 1991 CIA WORLD FACTBOOK. Retrieved 2022-7-9.

- ↑ "China GDP Growth Rate 1961-2022" (2022). macrotrends. Retrieved 2022-12-06.

- ↑ Deng Xiaoping (1987). To Uphold Socialism We Must Eliminate Poverty. [MIA]

- ↑ Wenjuan Tao, Zhi Zeng, et al. Towards universal health coverage: lessons from 10 years of healthcare reform in China. BMJ Global Health. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002086 [HUB]

- ↑ Wenjuan Tao, Zhi Zeng, et al. Towards universal health coverage: achievements and challenges of 10 years of healthcare reform in China. BMJ Global Health. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002087 [HUB]

- ↑ Lei Guang, Margaret Roberts, Yiqing Xu and Jiannan Zhao (2020). Pandemic sees Increase in Chinese support for regime, decrease in views towards the U.S. China Data Lab.

- ↑ Dan Harsha (2020). Taking China’s pulse. The Harvard Gazette.

- ↑ Yida Zhai (2018). Popular conceptions of democracy and democratic satisfaction in China. International Political Science Review. doi:10.1177/0192512118757128 [HUB]

- ↑ Wenbo Chen (2016). Is the label ‘minimal legislature’ still appropriate? The role of the National People's Congress in China's political system. The Journal of Legislative Studies. doi: 10.1080/13572334.2015.1134909 [HUB]

- ↑ Sam-Kee Cheng (2020). Primitive Socialist Accumulation in China: An Alternative View on the Anomalies of Chinese “Capitalism”. Review of Radical Political Economics, vol.52 (pp. 693–715). SAGE Publishing. doi: 10.1177/0486613419888298 [HUB]

- ↑ Changhong Pei, Chunxue Yang, Xinming Yang (2019). The Basic Economic System of China.. China Governance System Research Series. Springer Singapore. ISBN 978-981-13-6895-0 doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-6895-0 [HUB] [LG]

- ↑ China’s Collective and Private Enterprises: Growth and Its Financing, Table 2 by Shahid Yusuf

- ↑ China’s Collective and Private Enterprises: Growth and Its Financing, Table 15 by Shahid Yusuf

- ↑ Page 86, Is China still socialist? A Marxist critique of János Kornai’s analysis of China - Khoo, Heikoo.

- ↑ The Rise of the Investor State: State Capital in the Chinese Economy - Hao Chen and Meg Rithmire

- ↑ Hong Yu (2014) The Ascendency of State-owned Enterprises in China: development, controversy and problems, Journal of Contemporary China, 23:85, 161-182, DOI: 10.1080/10670564.2013.809990

- ↑ China reveals new top 500 enterprises list - Wang Zhiyong, China.org.cn

- ↑ Top 500 account for 78% of China's GDP - Biz.China, Xinhua.net

- ↑ OECD Review of Agricultural Policies - China ISBN: 9789264012608

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 Derek Scissors, Ph.D. “Liberalization in Reverse,” May 4, 2009, Published by The Heritage Foundation

- ↑ The SOE Premium and Government Support in China’s Credit Market - Zhe Geng and Jun Pan - November 29, 2022

- ↑ John Lee, “Putting Democracy in China on Hold,” May 28, 2008, Published by The Center for Independent Studies

- ↑ OECD Economic Survey China Sept. 2005 p83-95

- ↑ David Rosnick, Mark Weisbrot, and Jacob Wilson, The Scorecard on Development, 1960–2016: China and the Global Economic Rebound, 2017

- ↑ Peter Nolan, China’s Rise, Russia’s Fall, Palgrave Macmillan, 1995

- ↑ Chinese government now controls the main stake in McDonald's China business

- ↑ China Joint Ventures: Everything You Should Know - China Law Blog, Harris Bricken

- ↑ Hongyi Chen The Institutional Transition of China’s Township Village Enterprises. p5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315211305

- ↑ "Township Enterprise Law of the People's Republic of China"

- ↑ Professor Philip Alston (2016-9-23). End-of-mission statement on China, by Professor Philip Alston, United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

- ↑ Chuliang Luo, Shi Li, Terry Sicular (2020). The long-term evolution of national income inequality and rural poverty in China. China Economic Review. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2020.101465 [HUB] [LG]

- ↑ Our World in Data. Death rate from malnutrition, 1990 to 2017.

- ↑ Our World in Data. Share of the population living in extreme poverty, 1990 to 2016

- ↑ Anton Cheremukhin, Mikhail Golosov, Sergei Guriev, Aleh Tsyvinski (2015). The Economy of People’s Republic of China from 1953. National Bureau of Economic Research. doi: 10.3386/w21397 [HUB]

- ↑ "Africans approve of China, says Afrobarometer" (2016).

- ↑ Deborah Brautigam, Xinshen Diao, Margaret McMillan, Jed Silver. Chinese investment in Africa: How much do we know?. Policy Insight Series. [PDF] Private Enterprise Development in Low Income Countries.

- ↑ Ficawoyi Donou-Adonsou, Sokchea Lim (2018). On the importance of Chinese investment in Africa.. Review of Development Finance. doi: 10.1016/j.rdf.2018.05.003 [HUB]

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Amanda Yee (2022-12-19). "Why Chinese ‘debt trap diplomacy’ is a lie" Liberation News. Archived from the original on 2022-12-20. Retrieved 2022-12-23.

- ↑ Shang Guan Jie Wen (2022-02-23). "China Forgives Tens of Billions of Dollars in Debt for Africa" China and the New World. Archived from the original on 2022-02-23. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- ↑ Uncredited (2009-07-07). "China Blocks Access To Twitter, Facebook After Riots" Tech Crunch. Retrieved 2023-03-27.

- ↑ christineb (2020-05-29). "UYGHUR HUMAN RIGHTS POLICY ACT BUILDS ON WORK OF NED GRANTEES" National Endowment for Democracy. Retrieved 2023-27-03.

- ↑ Xi Jinping (2015). Opening up new frontiers for Marxist political economy in contemporary China. Qiushi Journal.

- ↑ https://www.businessinsider.com/chinese-billionaire-spoke-against-government-sentenced-18-years-prison-2021-7

- ↑ https://www.deccanherald.com/opinion/disappearing-billionaires-1195107.html

- ↑ https://news.bloomberglaw.com/environment-and-energy/lavish-chinese-villas-tumble-to-make-room-for-parks-pandas

- ↑ Phoebe Zhang (2021-12-21). "For LGBTQ people in China the picture is mixed, global report finds, with some legal protections but barriers to freedom of expression" South China Morning Post.

- ↑ Zhang Wanqing and Li Jiaru. (2021-11-08) "China’s First Clinic for Trans Youth a ‘Good Step,’ Advocates Say." Sixth Tone.

- ↑ "LGBT in China: Changes and Challenges" (22-Jan-2018). CGTN.

- ↑ Wang, Yuanyuan, Zhishan Hu, Ke Peng, Joanne Rechdan, Yuan Yang, Lijuan Wu, Ying Xin, et al. “Mapping out a Spectrum of the Chinese Public’s Discrimination toward the LGBT Community: Results from a National Survey.” BMC Public Health 20, no. 1 (May 12, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08834-y. Archived 2022-10-10.

- ↑ "A Day of Trans 跨越性别的一天". Yennefer Fang, Yennefer Fang Studios. YouTube. Archived 2021-11-28.

- ↑ Ji Yuqiao. “New Documentary ‘a Day of Trans’ Explores Experiences of Three Generations of Chinese Transgender Persons." Global Times. November 19, 2021. Archived 2022-09-17.